-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Tahrir Square through Two Transitions by Khaled Adham

“Massive demonstrations were organized,” writesFatemah Farag, “which included students marching from Giza to the center of Cairo. However, when the demonstrators reached the Square…four armed vehicles moved towards them and a barrage of machine-gun fire opened up. According to the most reliable estimate, 23 demonstrators were killed and some 120 injured. The government disclaimed all responsibility and blamed students for allowing their peaceful demonstrations to degenerate into violence because of infiltration by the riffraff.”

“Massive demonstrations were organized,” writesFatemah Farag, “which included students marching from Giza to the center of Cairo. However, when the demonstrators reached the Square…four armed vehicles moved towards them and a barrage of machine-gun fire opened up. According to the most reliable estimate, 23 demonstrators were killed and some 120 injured. The government disclaimed all responsibility and blamed students for allowing their peaceful demonstrations to degenerate into violence because of infiltration by the riffraff.”

No, this is not Tahrir Square in February 2011, the epicenter of the revolution that toppled the Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak’s regime earlier this month. It is Ismailia Square in February 1946, just a few years before it was renamed Tahrir Square. The demonstrators proclaimed it Evacuation Day, anticipating the departure of British forces occupying Egypt. According to a leaflet issued at the time, “the day was to make it clear to the British imperialism and to the world that Egyptian people have completed their preparation for active combat until the nightmare of imperialism that has crushed our hearts for 64 years has vanished.” Anti-Mubarak protesters evoked this history when they declared Friday 3 February the Day of Departure for the long-ruling president.

Future urban historians will perhaps mark these two Februaries as signposts of transitions among three significant periods in the history of modern Egypt: Colonial, Postcolonial, and Post-Postcolonial periods. The square has witnessed more than a century-and-a-half of urban, cultural, and political history, and the transitions between these three eras played out within its bounds. Here are some scenes from this dense, intricate history.

Early in the 19th century, during the colonial era, the area that would become Tahrir Square consisted of rough ground interspersed with marshes and ponds that were replenished with each summer flood. Toward the middle of the century, the scene began to change. Several royal palaces were constructed along the River Nile, with much of the land around them drained, filled, and planted. One of these was Qasr al-Nil. First used as a palace for the ruler, it was then retrofitted to serve as the Ministry of War. Eventually it came to serve as barracks housing the Egyptian army.

The palaces set the pattern for further development in 1867 by Khedive Ismail, Egypt’s modernizing ruler during the 1860s and ’70s. Between 1867 and the turn of the 20th century, the square took much of its current urban form. In his love of urban embellishments, and in preparation for the opening of the Suez Canal, Ismail began to expand the city by building an entire new district on the medieval city’s western edge. This area, Ismailia, became Cairo’s European Quarter, now downtown Cairo.

In order to carve out a large square that would function as a link, through Qasr al-Nil bridge, between the new district and the west bank of the Nile, or to Ismail’s palace in Giza and the newly constructed road to the pyramids, Ismail gave one of his palace gardens to the government. At that point, the new square, Ismailia Square, was nearly surrounded from all sides by military barracks, palaces, and villas. One new palace worth mentioning here is that of Ahmed Khairy Pasha, a complex that later became the Genaclis Cigarette factory, then Cairo University, and finally in 1919 the American University of Cairo.

Although it was the largest square in Cairo, Ismailia Square was never considered the center of the city. This honor was reserved to ’Abdeen and Opera squares, one mile to the east and northeast of Ismailia, respectively. Indeed, Ismailia Square was associated with hated occupation and colonization, since the British troops had taken over Qasr al-Nil barracks as part of their conquest of the whole country in 1882.

A new century brought new buildings. Designed by a French architect in a neo-classical style and marked as the first building in Egypt built with reinforced concrete, the Egyptian Museumopened its doors in 1902. This was followed by a series of apartment buildings replacing the villas that previously had flanked the square’s northern and eastern sides. The middle of the 20th century witnessed a few significant alterations. First, the Qasr al-Nil barracks were evacuated in 1947 and torn down in 1951 to make way for modern developments. Second, construction of Mogamma, a large administrative building designed by the Egyptian architect Kamal Ismail and given as a gift by the Soviet Union, was initiated in 1950.

The year 1952 ushered in a new post-colonial era to Egypt. As if answering Henri Lefebvre’s prophetic observation that any revolution that has not produced new spaces “has not changed life itself but has merely changed ideological superstructures, institutions or political apparatus,” the revolutionary officers reinvented the square as the center for postcolonial Cairo, and they renamed it Tahrir, or Liberation, Square. Three buildings represented this new era: the Nile Hilton, designed by an American firm in 1958; the Arab League Headquarters, designed by the Egyptian architect Mahmoud Riad in 1964, and the Socialist Union Headquarters, which later housed the National Democratic Party (the party of Mubarak), and which burned during the recent uprising.

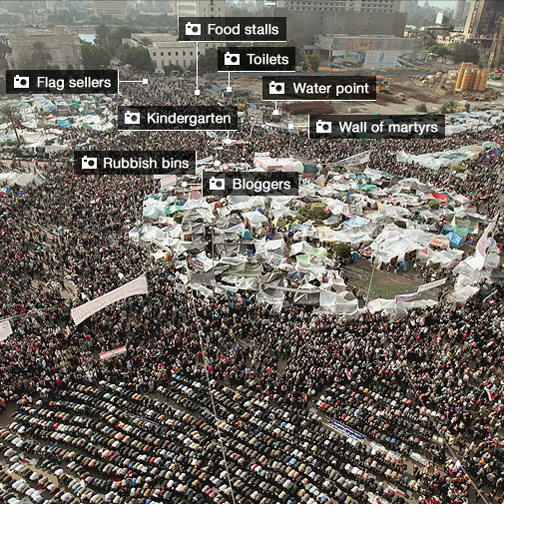

In the five ensuing decades, View Larger Map" target="_blank">Tahrir Square was a transportation hub, a governmental center, and a place for tourists. It also became a space for public expression, a place where demonstrations and funerals took place throughout the years. Physical alterations were limited to changes in landscape and the construction of underground garages and Metro station and tunnels. A recent visionary master plan for Cairo, however, revealed the intention of the Mubarak government to introduce changes that might have deprived the square of its centrality: relocating the Egyptian Museum to the Giza plateau and moving most of the governmental agencies to New Cairo.

It is not clear whether any of these plans will unfold in the next few years, but recent events pose questions, among them: how will Cairenes reinvent Tahrir Square in the emerging post-postcolonial era? What new spaces of civic representation and civil society will emerge from the transition now underway?

-- Khaled Adham

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top