-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Architectural History: College Prep 2013

Can architectural history empower? John Ruskin answered affirmatively with pragmatic initiatives that challenged the obvious associations of architectural capital and hegemony. Ruskin made his students at Oxford strip to their waists and build roads, he published letters to working class readers (Fors Clavigera), established utopian NGOs (Guild of Saint George), and developed curricula for technical schools. As Dolores Hayden has shown, the "power of place" and social justice have been an integral component of architectural discourse in the U.S. In the spirit of Ruskin's, however, architectural history's engagement with the community needs constant reaffirmation, especially recently, when educational resources for the arts and humanities have been dwindling in secondary education.

With Ruskin in mind, I decided to take up a challenge raised by Daniel Porterfield, President of Franklin & Marshall College where I teach. For three weeks, I taught a class for high-achieving high-school students from under-represented groups. Porterfield recognizes how the landscape of liberal arts education is changing and seeks new strategies like the College Prep Program (see here and here). For a pricey private college like mine, this is a critical conversation to have. So, I joined a group of seven fellow faculty members in teaching 72 students that came to our campus from 13 states, typically from extremely urban or extremely rural settings. The task of each class was to immerse the rising juniors into a college-level academic environment and inspire them to seriously consider the possibilities of college. The program hopes to inspire the students towards the necessary steps required for college planning during senior year, but also to help them decide what type of college fits them best. A few College Prep students end up applying to liberal arts colleges, which were previously not part of their familiar horizon.

In this post, I would simply like to share some of my lessons from this experience of teaching architectural history to high-school students. The conceptual framework for my class was to teach the students a rudimentary framework (ancient, medieval, modern), as well as a crash-course in methods of historical analysis. The strategy can be summarized in a few points.

- JSAH's Vitruvian motto "Utilitas, Firmitas, and Venustas" provided the conceptual framework, guided by James O'Gorman's beloved textbook ABCs of Architecture. The Architecture Handbook developed by the Chicago Architecture Foundation was another alternative. With function, construction, and beauty as the core conceptual unities, the students learned how to produce the requisite plans, sections, and elevations. My history lessons were condensed and sought to produce a basic framework that moved across the conceptual triad.

- Using our college campus as a virtual laboratory, the students learned how to make analytical drawings (measured and sketchy) as a way to substantiate observations about architectural meaning. We focused on four buildings, a Gothic Revival Main Building (1856), a Richardsonian seminary (1893), a Colonial Revival science building (by Charles Klauder, 1925), and a college center (by Minoru Yamasaki, 1972). Forced to distill all observations in a sketchbook, the students were able to see history in action as it unfolded across these four buildings. The classical, medieval, and modern traditions were recognized as coherent vocabularies with their own elaboration on the function-structure-beauty synthesis.

- None of the students had any background in architectural drawing. Although rudimentary at first, the sketchbooks proved to be a good discipline (see examples below). At the end of the seminar, the students formed teams and measured the facades of two designated buildings. The objective was to produce a drafted final drawing.

- Field trips provided additional inspiration. We visited our college's Archives to look at original architectural drawings produced by Klauder's and Yamasaki's offices. We also visited our college museum, where we analyzed architecture represented in paintings, and asked the question of what is the intended representational content of architecture in art. Our day-long field trip to Lancaster gave us a chance to talk about the American city from the Colonial period to urban blight and post-industrial revivals.

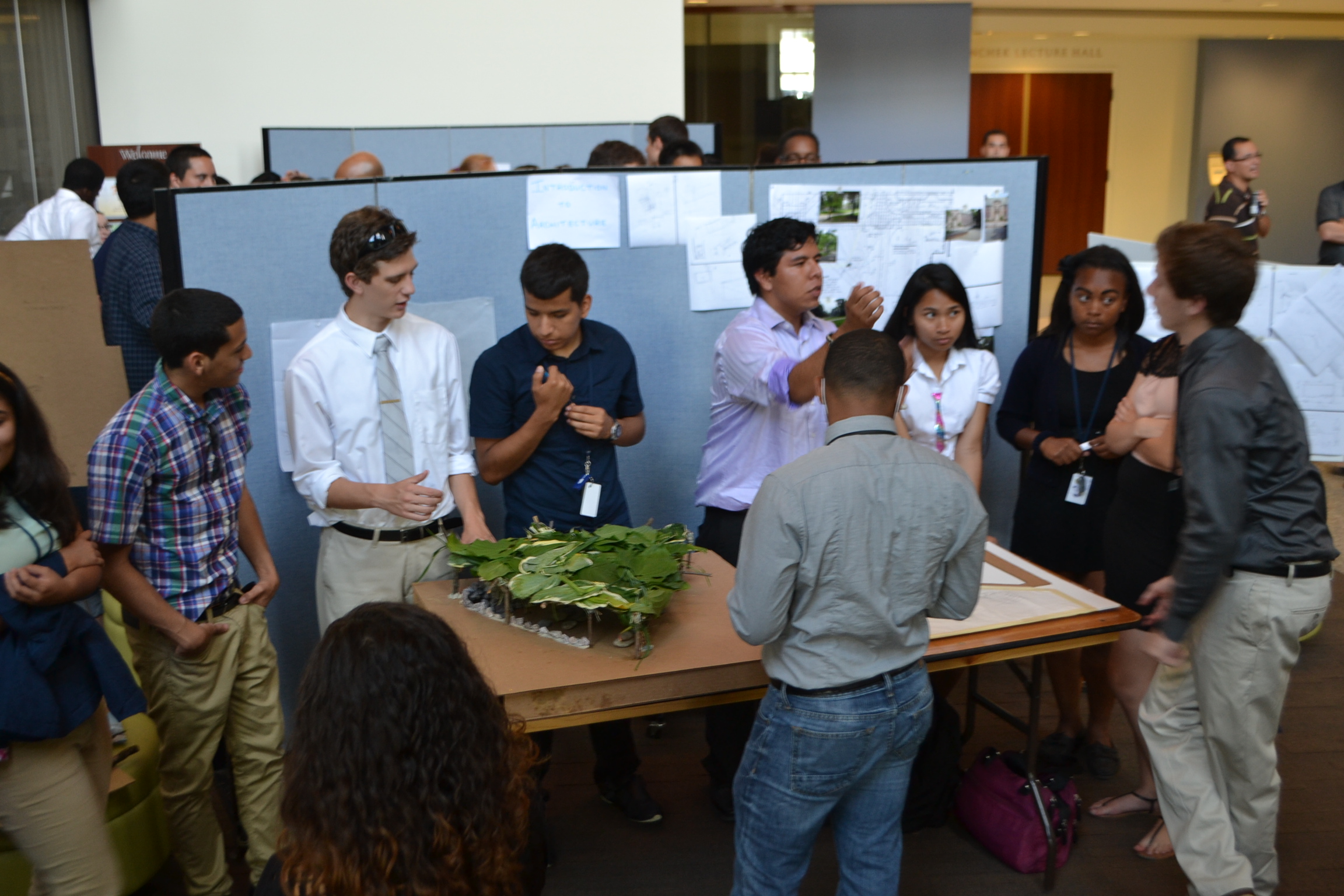

- At the end of the seminar, the students presented their work to the rest of the students and faculty at a final Fair. A studio component taught by my colleague Carol Hickey concluded with the design of a primitive hut in the tradition of Vitruvius and Laugier. This pavilion was sited among the historical buildings that the students had already measured in my documentation exercises.

What did I learn from this program? For one, it was a great pleasure to teach students from a diverse socio-economic background where architecture was not simply another item of consumption. It dawned on me that architectural history must serve under-represented social classes in different ways. If the upper social classes live in newly-created architectural fabrics (McMansions, suburbs, etc.), the lower social classes become the occupants of the abandoned older housing stock. Even if they share the dream of leaving the dilapidated inner city or rural farm behind, they are the rightful custodians of its heritage. Economic mobility translates into geographic mobility, which typically takes place across a historical journey from old discarded architecture to fancier, better maintained, newer architecture. But getting out of the old should not be the only form of empowerment. Understanding the old, which is now yours, offers a different kind of ownership, of intellectual rather than real-estate capital. Architectural heritage has an interesting class component. Poverty and historical residue coincide.

With the social polarization of college education, architectural history is increasingly an interest to a social class uneasy with the architectural realities of American cities. The majority of my students come from the suburbs. They feel extremely uncomfortable in the city, unless it is the manicured commercial experience of Manhattan, or any other gentrified downtown. When we take trips into the cities-of-old to witness masterpieces of historical architecture, we must also confront social realities. Teaching to non-elite kids proved to be completely different. There were no touristic obstacles to be overcome. The old was part of home.

I must confess that my foray into Ruskinian social justice has been new and novel. I know that many members of the SAH have been doing this for much longer than I. The experience has opened my eyes and introduced me to similar programs like the The Social Justice Research Academy at the University of Pennsylvania, where landscape architect Michael Nairn teaches on public space and urban sustainability. I also learned about tour classes offered by the Chicago Architecture Foundation and the initiatives by other universities to provide summer experiences on architecture: Career Explorations in Architecture at Tulane University, ArcStart at the University of Michigan, Experiment in Architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology, Career Discovery at Notre Dame, Exploration of Architecture at University of Southern California, and others. Such programs are hosted by design schools and focus on the profession of architectural practice. An agenda in architectural history and interpretation has a slightly different trajectory and expectations.

It would be interesting to hear from other architectural historians that have had similar experiences in reaching out to high school students. I would love to post your experiences on this blog, please send me an email at kkourelis@gmail.com.

I conclude with a couple of drawings from the students; sketchbooks:

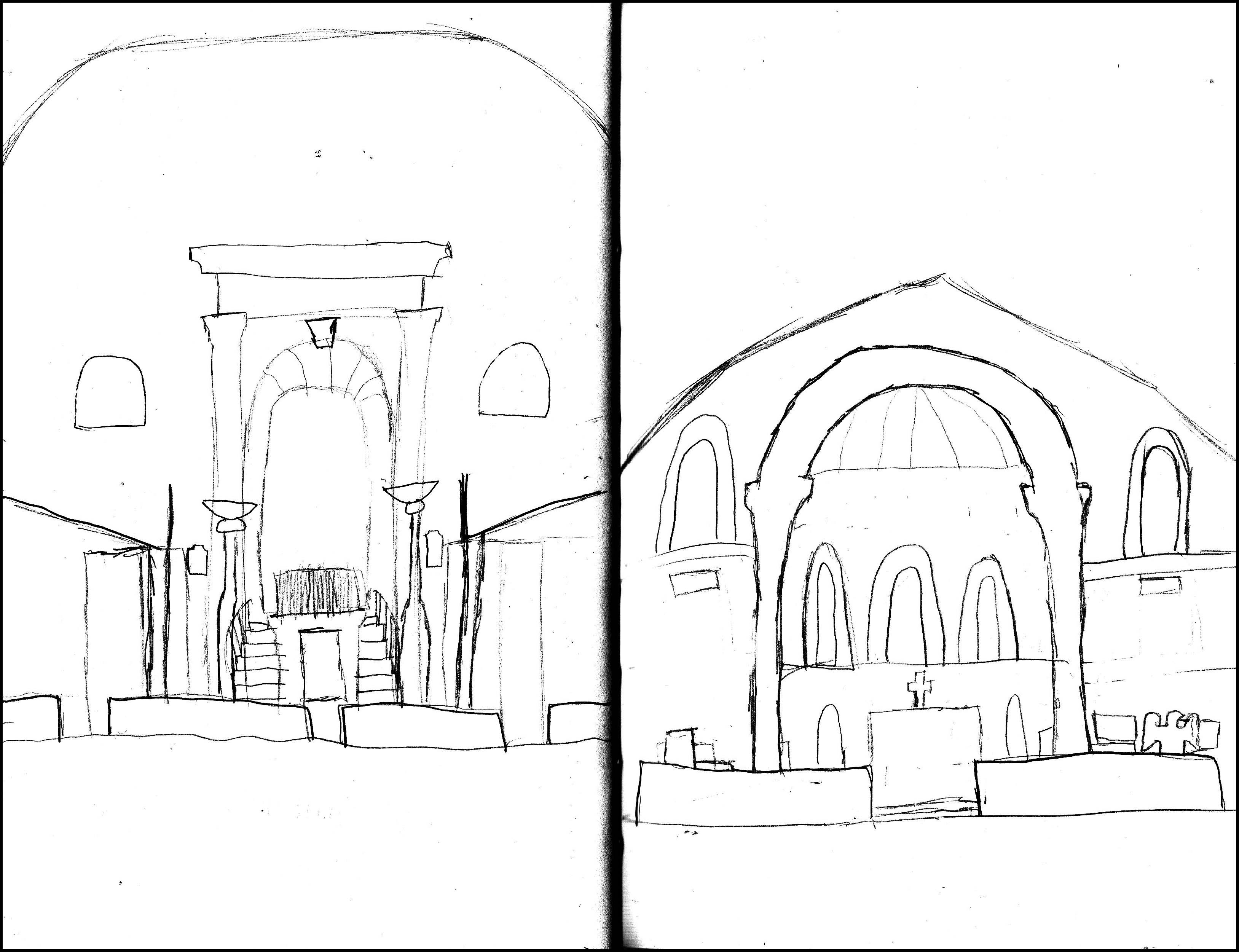

Quick sketch exercise by Zachary Maneval comparing two 19th-century

churches, Trinity Lutheran and James Episcopal in Lancaster. Although

not professional or measured, the sketches illustrate the spatial and

aesthetic difference between two radically different spaces and

denominations.

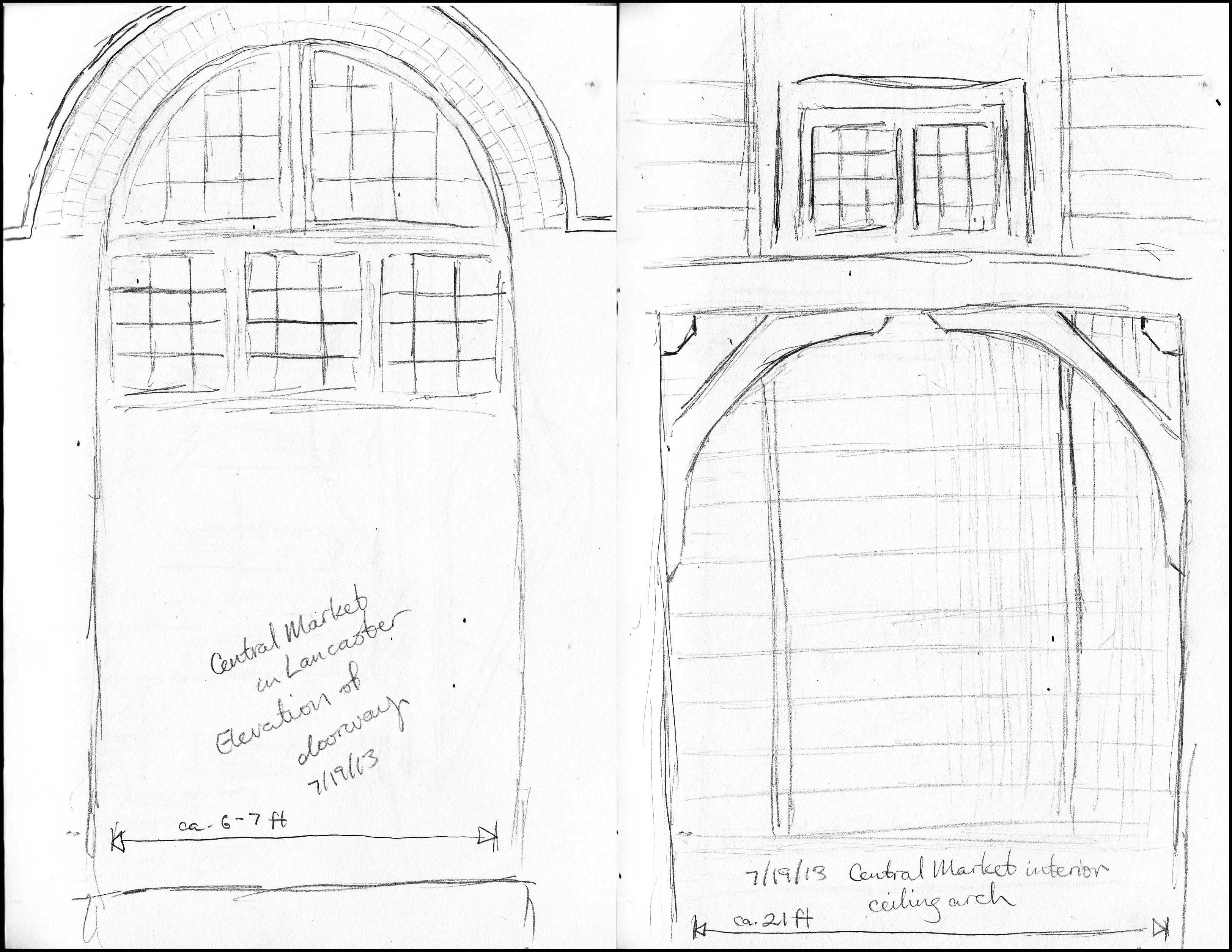

Quick sketch exercise by Lara Elizabeth Vera of interior facade of

Central Market, Lancaster, investigating the relationship between

structural material and visual order.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top