-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

The New Flower: Addis Ababa and the Project of African Modernity

He is a young man.

He is a young man

by a steel track.

He wants the streets

to be more than streets.

The Italian boulevard

the Italians built

to be more

than a boulevard.

The city more

than a city.

He has high,

admirable ideals.

It is a dangerous world.

The emperor

is such a powerful

man. The Derg

and the military

the most violent

letdown.

Excerpt from “The Track,” Lena Bezawork Grönlund Callaloo 33, no. 1 (Winter 2010): 295-296

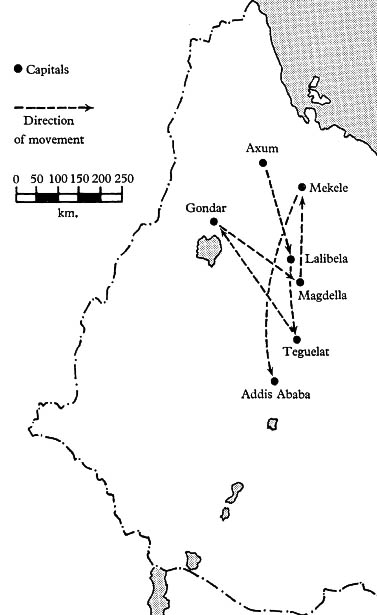

Addis Ababa, or “New Flower” in Amharic, was founded in 1886. During early imperial times the capital had been located in Axum, Lalibela, and Gondar, as well as several other smaller cities. In modern times, the capital was built anew. Empress Taytu Betul, wife of Emperor Menelik II, first settled in the Entoto hills. This settlement was “little more than a military encampment.”1 She later moved to a valley in the foothills, attracted by natural hot springs on land called Finfinne by the Oromo people who lived there. As historian Getahun Benti argues, “From its earliest days, Addis Ababa was the staging station for the economic exploitation and political control of the conquered provinces of which Oromia was the largest.2 It was at Finfinne that Empress Taytu Betul renamed the city “Addis Ababa,” a strong proclamation of the ambitions of both Taytu and Emperor Menelik II.

Figure 1. Major capitals of Ethiopia. Ronald J. Horvath, “The Wandering Capitals of Ethiopia,” Journal of African History 10 no. 2 (1969): 208

Figure 2. Partial view of Menelik II’s Palace in the area formerly known as “Gebi,” now grounds of Prime Minister’s residence. Source: Ethiopundit.

Many recent texts on Addis Ababa explore the founding of the city as a project of modernity, one that Emperor Menelik II undertook after successfully conquering portions of what is today the southern region of Ethiopia. Menelik II’s reign, from 1889 to 1913 brought into existence the modern borders of the country, and he chose to rule from a central location, symbolically bringing together the northern and southern regions. The question of modernity as it applies to Addis Ababa, however, has yet to be answered. This is a direct result of the fact that modernity itself is subject to different definitions and interpretations. Menelik II, in his diplomatic relationships with various countries, believed he was creating the modern state of Ethiopia. His defeat of the Italians at the Battle of Adwa in 1896 proved that Ethiopia had the military prowess to fend off colonization in the “scramble for Africa.” Yet, by the time Emperor Haile I Selassie fled to England as the Italians invaded Ethiopia from Eritrea in 1935, Italian claims of Ethiopian primitivism served as fodder for their imperial conquests.

Figure 3. What does it mean to be a modern African capital? View up Churchill Avenue.

Early Industrialization and Urbanization in the Imperial City

The narrative arc of the Addis Ababa Museum, established in 1986 on the centennial of the city’s founding, explained how the city became the epitome of a modern, cosmopolitan entity within a few decades. Exhibition material in Finfinne Hall of the museum highlighted the beauty of the highly detailed wooden structures erected under the early part of Menelik II’s reign. The craftsmen for these structures came from various regions that had trade relationships with Ethiopia, including India. Menelik II's palaces at Finfinne and Addis Alem show clear Indian detailing and architectural motifs. The next room in the museum focused on Alfred Ilg, a Swiss engineer who brought a significant amount of industrial technology to the country (Ilg also extensively photographed Menelik II’s court). The rapid urbanization of the city of Addis Ababa after its founding, the cosmopolitan nature of the market spaces and trade relationships that brought foreign goods to Arada (later Piazza), the introduction of the rail line, electricity, bridges, and other feats of civil engineering are the hallmarks of Menelik II and Taytu’s reign. Mekonnen Worku, in his 2008 urban design master’s thesis proclaimed Menelik II “the great modernizer of Ethiopia.”3

Figure 4. Building on the complex of the Central Statistical Agency. While I have not yet discovered the original use of the building, guards told me it was the location of the first Bank of Abyssinia.

Figure 5. Residence in the Arada/Piazza area of Addis Ababa.

Figure 6. La Gare, constructed in the 1920s. This station linked land-locked Ethiopia to the port of Djibouti.

Even with the introduction of industrial technologies to the young capital, could one argue that the city was truly modern? Several scholars dispute the claim. Andreas Eshete, former president of Addis Ababa University, where he was also a professor of law and philosophy, argues “there is a crucial distinction between the advent of the idea of modernity on the one hand, and its psychological and institutional realization on the other.”4 He bases his argument on the fact that throughout the first 70 years of the city’s existence, the imperial powers, centrality of Orthodox Christianity, Italian Fascist presence, and communist rule disallowed “popular legitimate rule by free and equal citizens, the abolition of all privileges of birth or inherited position, equality of faiths and cultural communities, industrialization, and secularism.5” Indeed, Ethiopia was an imperial nation until the overthrow of Selassie in 1974, and operated under major themes of exceptionalism – Ethiopia of antiquity, with ruling parties claiming direct descent from the Queen of Sheba and King Solomon; Ethiopia, one of the earliest Christian nations; Ethiopia the modern nation that resisted European colonialism.

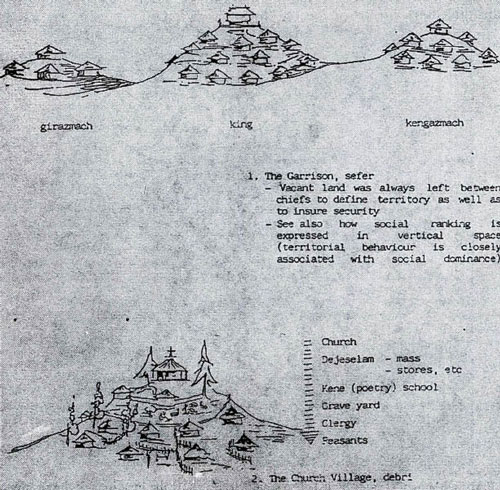

For much of the short history of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia has been a country of centralized power, resting with the looming historical figures of Menelik II, Selassie, and Mengistu. This factor allowed for the exploitation of Addis Ababa’s topography for expressions of power. Planning historian Dandena Tufa suggests that Empress Taytu was most influential in the early layout of the town. She wanted military officials and their soldiers to settle around the palace for purposes of defense, so the earliest settlements were on the high grounds of the Finfinne region. Additionally, Tufa states, “This original settlement layout was based on a traditional land use system that was derived from the settlement structure of the northern part of Ethiopia.6

Figure 7. Traditional territories in vertical space: garrison “säfär” and a church with village development from Dandena Tufa, “Historical Development of Addis Ababa: Plans and Realities,” Journal of Ethiopian Studies 41 no. 1/2 (June-December 2008): 34

Military and political officials associated with the imperial power were literally “lifted” above the common people, “reshaping of [the] topography to locate and display differences and hierarchies of power, wealth, and status:”

The most elevated part of the city was reserved for the highest authority in the land—the king— subsequently becoming the nucleus of the city that was being organized concentrically. In a descending order, politically and geographically, land was allotted beginning from top officials to those at the bottom of the socioeconomic order.7

Embassies were situated close to imperial compounds, also on the high ground. Eshete also discusses how political control was a major factor that “pervaded the organization of Addis Ababa in the 1880s, the restructuring of its space under Italian colonialism in the late 1930s, and its modernization after the 1940s.”8

These physical realities were very clear to me (and my legs – what a workout!) as I visited significant architectural sites in Addis Ababa. The Addis Ababa Museum, former home of Ras Biru Wolde Gabriel (War Minister of Menelik II), the Beate Maryam Church (Menelik II Museum), the Holy Trinity (Selassie) Cathedral, the St. Giorgis Cathedral, and Ras Makonnen Hall (formerly Guenete Leul Palace, the residence of Haile I Selassie, and currently under the aegis of Addis Ababa University), were all on high ground. While I initially had not studied the planning of Addis Ababa before visiting these sites, the physical realities of their high positions were not lost on me. They certainly would not have been lost on a resident of Addis Ababa in the early stages of the city’s development.

Figure 8. Beate Maryam was accessible only after a steep climb up the Gebi hill on the grounds of the Prime Ministers residence.

Landscape designer and city planner Sara Zewde, who is currently pursuing her MLA at Harvard School of Design, has been a useful contact during my time in Addis Ababa. A U.S. born second-generation Ethiopian, she split her childhood between New Orleans and Houston. Her research and work has helped me think about urbanism in the Global South in new and exciting ways. Zewde put me in touch with Brook Teklehaimanot, a practicing architect and professor at the Ethiopian Institute of Architecture, Building Construction, and City Development. Teklehaimanot supplied me with the basics of urban development in Ethiopia, and the challenges the city faces today as it undergoes rapid growth and construction.

Brook Teklehaimanot Lecture “Addis and its Urbanism”

Italian Colonialism or, The Occupation 1936-1941

“They got hopes and plans a getting’ rid of me

I hit ‘em like Ethiopia hit up Italy”

Black Thought of The Roots

“The Show (Must Go On)” feat. Common and Dice Raw

Rising Down, 2008

I was sitting in my bed reading about the history of Addis Ababa while listening to the unparalleled, multiple Grammy award winning, hip-hop band The Roots when that song lyric resounded in my ears. I was reinvigorated by the intersection of my love for hip-hop with my quest to understand Ethiopian history. One will find, within scholarly texts on Ethiopia that focus on the period between 1936 and 1941, various methods of referring to the Italian presence in the country. The decision to call the time period an occupation, as many pro-Ethiopian and nationalist publications suggest, or colonization, as many studies on Italian Fascism suggest, is a truly political statement. Ethiopian resistance to European colonization is a central part of its historical memory/mythology and exceptionalism. Most architectural publications on the subject, interestingly enough, choose to describe the period as one of colonization.

Ethiopia, along with Libya, Eritrea, and Italian Somaliland were the countries that made up the entity of l'Africa Orientale Italiana. This region became a site of “engage[ment] in the mystical discovery of the former Roman presence, to feel the miracle of an ancient society coming to life, and to sense a vital spiritual connection with the past.”9 The Italian presence had tangible consequences for Ethiopians. Italy began a campaign of “modernizing” the region in the language of Italian Fascist architecture. Urban plans recreated pre-existing cities into the utopia of an Italian regime. Le Corbusier even submitted a plan for Addis Ababa to Mussolini based on his Radiant City scheme. Thankfully, many of these plans were not fully realized. Architectural developments came in the form of public and governmental buildings such as post offices, banks, and administrative centers. These were the objects of empire, in the same way (though on a much smaller scale) that the circus and theaters of the ancient Roman Empire were established in colonial cities.

Ethiopians in Addis Ababa as well as other major cities in the “Italian Empire” were subject to “racial segregation at all levels:”

In the Fascist version of apartheid, districts of all major towns were reserved exclusively for white settlers, conjugal relations between Italians and Africans were criminalized, collective activities were prohibited. The relationship between settlers and subjects was organized along hierarchical lines. In all accounts of empire, the indigenous population was represented as the other of the new imperial structure.10

These ideals were adapted to the topographical realities of Addis Ababa. While Italian master plans for the city did not acknowledge the topographical layout of the site, the need of Italian imperial powers to be seen as domineering was easily adaptable to the layout of Ethiopian imperial hierarchy in the city. Cultural anthropologist Mia Fuller discusses the implications of Italian segregation practices in the forms of “exposure and visibility.” She argues “The guiding principle was to make blacks, except insofar as their 'quarters' needed to be supervised, as invisible as possible to whites, and to make whites as visible as possible to blacks, in a public, though not a private sense.”11 This discourse on visibility reminded me of several passages I had read many years before in “Duality and Invisibility: Race and Memory in the Urbanism of the American South,” in the volume Sites of Memory: Perspectives on Architecture and Race, written by Craig Barton, current Director of The Design School at Arizona State University. There were also similarities to Getahun Benti’s description of the subjugation of the Oromo peoples in the early founding of Addis Ababa in “A Nation Without a City [A Blind Person Without a Cane]: The Oromo Struggle for Addis Ababa.” One thing that was significant in this intersection of discourse, however, was that ethnic and racial dominance in an urban setting often depended on intricate social engineering of interactions within the public sphere.

The Promise of Pan-African Modernity

The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) was established in 1958, while the Organization of African Unity (OAU) was founded in 1963, both in Addis Ababa. Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah was a vocal advocate for the founding of the OAU (now known as the African Union, or AU). There was a particular kinship between Ghana and Ethiopia, Kwame Nkrumah and Haile I. Selassie. It is not a coincidence then, that the first Encyclopedia Africana that W. E. B. Du Bois published while in Ghana actually covered the two countries together. Here the claims for exceptionalism that put the two countries at the forefront of the Pan Africanist movement were strong. Ghana, the first sub-Saharan African nation to gain independence, and Ethiopia, the only nation in Africa to resist European colonization.

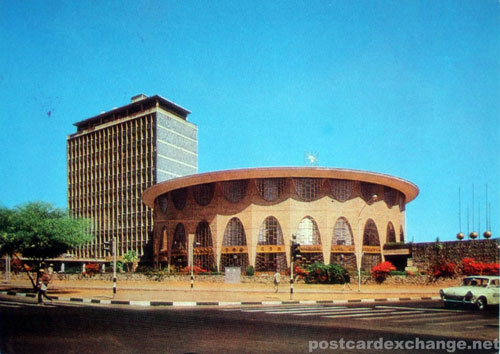

Figure 9. UNECA building, constructed 1961 by Italian architect Arturo Mezzedimi. It was expanded in 1975.

Similar to Accra, Addis Ababa looked to outside architects to define its post-war, Pan-Africanist modernity (foreign architects had significant influence in the construction and erection of the most important buildings in Addis Ababa since its founding). The Goethe-Institut in Addis Ababa hosted an exhibition in December 2013 entitled “Addis Modern: Rediscovering the 1960s Architecture of Africa’s Capital City,” that “focus[ed] on series of buildings with contextual, structural, monumental, formal, minimal and sculptural approaches to architecture.”12

Examples were numerous. Along the monumental Churchill Avenue, laid out by French planner L. De Marien in the 1960s, I found the Ethiopian National Theatre (completed in 1955), the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia, and the Ethiopian Television and Radio Building. They all possessed a very sculpture quality in their construction, and were “modern” landmarks along the Addis Ababa street that was inspired by the Champs-Elysees. To be clear, these singular moments along the street did not give the same type of coherence of urban fabric that one would find in Haussmannian Paris.

Figure 10. Commercial building near Churchill Avenue.

Figure 11. Undated postcard image of the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia on Churchill Avenue. Source: Postcard Exchange.

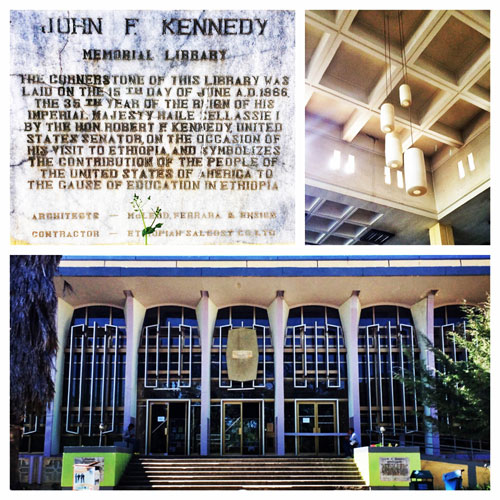

Another major public work that was created during the 1960s is the John F. Kennedy Library on the campus of Addis Ababa University. The John F. Kennedy Library is situated slightly off the ceremonial path of the university campus that leads from its historic gates to Ras Makonnen Hall. And here is where things get exceedingly interesting. The Washington-based architecture firm McLeod, Ferrara, and Ensign, designed the John F. Kennedy Library. McLeod, Ferrara, and Ensign, at the same time, was working on the construction of Howard D. Woodson High School in Northeast Washington, D.C. They completed the design for Howard D. Woodson High School in 1972; the school was demolished in 2008. The building was featured prominently in my dissertation “Concrete Solutions: Architecture of Public High Schools During the Urban Crisis.” So when I trekked off the main path of Addis Ababa University to see the John F. Kennedy Library (as an American I felt it was my duty somehow, strange as that sounds) I was completely floored by the discovery of the architecture firm.

Figure 12. John F. Kennedy Library on the campus of Addis Ababa University.

Addis Ababa Today: Modernity and Heritage

Addis Ababa is an exceedingly young capital in a country with an amazing historical legacy, however none of the UNESCO World Heritage sites listed for Ethiopia are located in the country’s capital. Neither are any of the tentative sites. This does not mean that Addis Ababa lacks architectural heritage worthy of preservation. The United States Embassy in Addis Ababa received the U.S. Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation in 2007 for the restoration of the Mohammed Ali House. According to the World Monuments Fund website, which listed the building on its watch in 2008:

Minas Kherbekian, a well-known Armenian architect from the region, constructed the house to be the headquarters of the powerful trading firm G.M. Mohammadali. The structure echoes the diversity of styles and materials of the buildings surrounding it, exhibiting traces of Indian, Arab, and Ethiopian influences.13

U.S. Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation is a truly exciting initiative from the Department of State, granting direct funds to projects around the world. The work of preservation should not just rest with organizations dedicated to architecture, but those dedicated to the political diplomacy as well.

The socio-cultural battle for Addis Ababa, the modern “capital city of Africa” is not yet over. The struggle is embedded within the urban fabric of the city through the erection of key political and cultural buildings. The Oromia Cultural Center, currently under construction, carries with it the hopes of the Oromo people to re-establish authority in the capital city. The Architectural Design and Research Institute of Shanghai’s Tongji University designed the new African Union building, the tallest building in the Addis Ababa skyline. The Chinese government funded construction. Scholar Lloyd G. Adu Amoah argues Chinese “soft imperium” is undermining African claims of sovereignty and modernity in Addis Ababa as well as in Accra. The topic of Chinese involvement in rapidly expanding African cities is also covered in design critic Justin Zhuang’s Metropolis article “How Chinese Urbanism Is Transforming African Cities.” Visible presence in the built environment of the city is important for entities seeking legitimization and a strengthened profile in the African capital city. Historian Shimelis Bonsa Gulema in “City as Nation: Imagining and Practicing Addis Ababa as a Modern and National Space,” contends:

On the one hand, the multiplicity of narratives demands constructing the city as a city of modernity, but also as a modern city of tradition, a city that could negotiate between its past and the past of the nation on the one hand and the modernist aspirations of its leaders and occupants on the other. It also requires cultivating and displaying the city’s various origins and characters as Ethiopian, African, and cosmopolitan urban space but also as national, imperial, and revolutionary.14

This has been the dilemma of the “New Flower” and the project of African modernity in the twentieth century. There is money to be spent in Addis Ababa, evident by the McMansions sprouting up in the stylish Bole area. Despite a conservative culture, Ethiopians are also avant-garde and trendy, as fashionistas strolling down major thoroughfares can confirm. There is a palpable energy in Addis Ababa (also felt in Accra) that the city is contributing to the trend of “Africa Rising” in the twenty-first century. The city has been banking on the notion since 1886.

Figure 13. Lion of Judah statue. Junction of Churchill Avenue and plaza in front of La Gare. Construction of new elevated metro seen in lower region of photograph, as well as construction of skyscraper to the right.

H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship Google Map

Recommended reading:

Hussein Ahmed, “Faith and Trade: The Market Stalls around the Anwar Mosque in Addis Ababa during Ramadan,” Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 19 no. 2 (1999): 261-268

Getahun Benti, “A Nation Without a City [A Blind Person Without a Cane]: The Oromo Struggle for Addis Ababa” Northeast African Studies 9 no. 3 (2002): 115-131

Charles Burdett, “Italian Fascism and Utopia,” History of the Human Sciences 16 no. 1 (2003): 93-108

Maurice De Young, “An African Emporium, The Addis Märkato,” Journal of Ethiopian Studies 5 no. 2 (July 1967): 103-122

Mia Fuller, “Wherever You Go, There You Are: Fascist Plans for the Colonial City of Addis Ababa and the Colonizing Suburb of EUR '42,” Journal of Contemporary History 31 no. 2 (April 1996): 397-418

Elizabeth Wolde Giorgis, ed. Special Issue: Engaging the Image of Art, Culture, and Philosophy: Particular Perspectives on Ethiopian Modernity and Modernism

Northeast African Studies 13 no. 1 (2013)

Fasil Giorghis & Denis Gérard, Addis Ababa 1886-1941: The City and Its Architectural Heritage (Addis Ababa: Shama Books, 2007)

Shimelis Bonsa Gulema, “City as Nation: Imagining and Practicing Addis Ababa as a Modern and National Space,” Northeast African Studies 13 no. 1 (2013): 167-213

Ronald J. Horvath, “The Wandering Capitals of Ethiopia,” Journal of African History 10 no. 2 (1969): 205-219

Mark Jarzombek, “Fasil Giorghis, Ethiopia and the Borderland of the Architectural Avant-garde,” Construction Ahead (May-August 2008): 38-42

Belle Asante Tarsitani, “Linking Centralised Politics to Custodianship of

Cultural Heritage in Ethiopia: Examples of National-Level Museums in Addis Ababa,” African Studies 70 no. 2 (2011): 302-320

Dandena Tufa, “Historical Development of Addis Ababa: Plans and Realities,” Journal of Ethiopian Studies 41 no. 1/2 (June-December 2008): 27-59

Dagmawi Woubshet, Salamishah Tillet, and Elizabeth Wolde Giorgis, eds. Special Issue: Ethiopia, Literature, Art and Culture Callaloo 33 no. 1 (Winter 2010)

Mekonnen Worku, “Heritage Conservation Oriented Planning: Heritage Policy in Light of Sustainable Urban Planning, The Case of Piazza LDP, Addis Ababa,” (Master’s thesis, Addis Ababa University, 2008)

Mulatu Wubneh, “Addis Ababa, Ethiopia – Africa’s Diplomatic Capital,” Cities 35 (2013): 255-269

- “The Finfinne Hall,” Exhibit. Addis Ababa Museum.

-

Getahun Benti, “A Nation Without a City [A Blind Person Without a Cane]: The Oromo Struggle for Addis Ababa” Northeast African Studies 9 no. 3 (2002): 117.

- Mekonnen Worku, “Heritage Conservation Oriented Planning: Heritage Policy in Light of Sustainable Urban Planning, The Case of Piazza LDP, Addis Ababa,” (Master’s thesis, Addis Ababa University, 2008), 3.

- Andreas Eshete, “Modernity: Its Title to Uniqueness and its Advent in Ethiopia: From the Lecture What is ‘Zemenawinet? – Perspectives on Ethiopian Modernity,” Northeast African Studies 13 no. 1 (2013): 12.

-

Ibid.

-

Dandena Tufa, “Historical Development of Addis Ababa: Plans and Realities,” Journal of Ethiopian Studies 41 no. 1/2 (June-December 2008): 32.

-

Shimelis Bonsa Gulema, “City as Nation: Imagining and Practicing Addis Ababa as a Modern and National Space,” Northeast African Studies 13 no. 1 (2013): 171.

-

Gulema, 173.

-

Charles Burdett, “Italian Fascism and Utopia,” History of the Human Sciences 16 no. 1 (2003): 99.

-

Burdett, 102.

-

Mia Fuller, “Wherever You Go, There You Are: Fascist Plans for the Colonial City of Addis Ababa and the Colonizing Suburb of EUR '42,” Journal of Contemporary History 31 no. 2 (April 1996): 405.

-

The Goethe-Institut hosts a great variety of exhibits and talks on architecture and urbanism in Africa generally, and Addis Ababa more specifically.

-

“Mohammad Ali House,” World Monuments Fund http://www.wmf.org/project/mohammad-ali-house.

- Gulema, City as Nation, 191.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top