-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Byzantium on the Adriatic: From Ravenna to Poreč

My journey begins in Italy, in the city of Ravenna where I have spent time before. Planning my itinerary for July and August, it was a convenient point of departure for a round-trip overland (except for a ferry ride) that will take me to Croatia and Bosnia and will end in Venice. This is the first stop of an Adriatic itinerary that will take me from Italy to Poreč, inland to Zagreb, back to the coast in Split (Spalato), inland to Bosnia, to the coast in Dubrovnik (Ragusa), across the Adriatic to Bari, from there to Rome and finally to Venice. I will write about most of this journey in my post at the end of August, but now will start with Ravenna and Poreč, setting out some of the premises for my travels over the following weeks. Even though I specialize in Islamic art, I have strong interests in Byzantine and medieval architecture and hence have planned this trip which will allow me to see monuments that are not directly related to my research and have hence had to remain by the wayside so far. For this first blog entry, I will focus on monuments that are easily labeled late antique or Byzantine but, perhaps due to their respective locations in Italy and Croatia, are not such much at the center of attention as Byzantine architecture in Istanbul—Constantinople, the capital of the Eastern Roman empire from the fourth century until 1453. But more about this later, in my winter 2016 posts from Turkey— now, I will turn to the fifth- and sixth-century monuments of Ravenna, many of which are part of the UNESCO World Heritage. From 540 until 752, Ravenna was the center of Byzantine territories in Italy. The city was closely connected to Constantinople, where mosaics predating the tenth century are exceedingly scarce. Hence, the monuments of Ravenna are essential for any study of fifth- and sixth-century Byzantine mosaics and their restoration, and they have in fact been the subject of many studies.

Figure 1: San Vitale, Ravenna, view (P. Blessing)

Visiting Ravenna, I move around the city and its major monuments with a fresh eye. The first stop is the sixth-century church of San Vitale (Figure 1). Inside church, the mosaic decoration has been preserved in the apse, but not in the dome (Figure 2).

Figure 2: San Vitale, Ravenna, part of apse mosaic (left) and 18th-century paintings inside the dome (right)

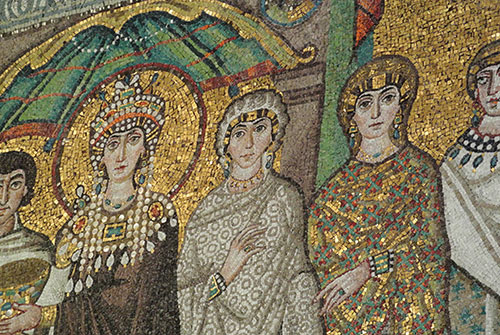

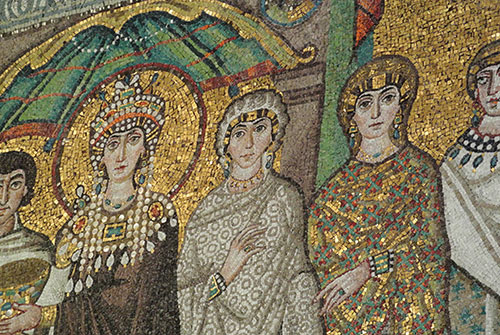

In both sides of the apse, mosaics show, to the left, the court of Byzantine emperor Justinian (r. 527–565) and, to the right, of his wife Theodora. Accompanying Justinian, we see bishop Maximianus during whose tenure (546–556) the basilica, commissioned by his predecessor Victor in 528, was completed (Figure 3). A detail of the court of empress Theodora shows the elaborate dresses and jewels with which both men and women of the court were represented (Figure 4).

Figure 3: San Vitale, Ravenna, mosaic showing Justinian’s court (P. Blessing)

Figure 4: San Vitale, Ravenna, mosaic showing detail of Theodora’s court; the empress is shown at far left (P. Blessing)

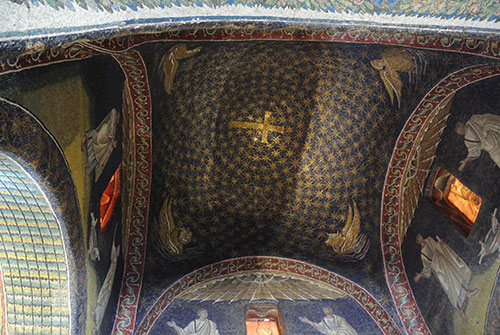

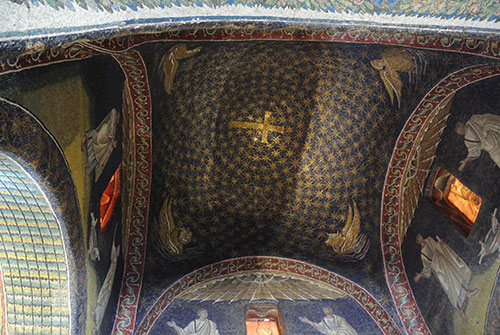

The next stop, just behind San Vitale, is the mausoleum of Galla Placidia (Figure 5), a small structure that houses another example of the splendid mosaics that Ravenna is famous for, although this is even earlier than San Vitale. The mausoleum was built for Galla Placidia, a sister of Roman emperor Honorius who moved his capital to Ravenna. According to local lore, she died in Ravenna in 452 and her sarcophagus was placed in the small structure, under a mosaic sky with gold stars (Figure 6).

Figure 5: Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Ravenna, view (P. Blessing)

Figure 6: Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, interior view of dome (P. Blessing)

At the basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, mosaics extend along the upper section of the central nave and into the apse. Begun in 493, construction of the church now dedicated to Ravenna’s patron continued into the early sixth century. The initial dedication to the Saviour was not changed until the early sixteenth century. Most notable—at least for historians of architecture— are the two representations of monuments that are included in these monuments. The first, to the right as one enters the church at its western end, is a symbolically complex representation of an imperial palace, one of many found in late antique and Byzantine art.1 Clearly labeled “Palatium” (palace, in Latin), the structure has open doors and windows with curtains flying in a light breeze (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Detail of mosaics in Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, showing palace (P. Blessing)

Figure 8: Detail of mosaics in Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, showing harbor of Classe (P. Blessing)

Facing the representation of the palace is one of a fortified city and harbor (Figure 8). Shown here is the harbor of Classe, near Ravenna. Even though it is no longer directly on the sea nowadays due to changes in water levels and silting, Ravenna and its port of Classe were important naval bases in the fifth and sixth centuries. The port of Classe, a 15-minute drive from central Ravenna, is a major archaeological site. Together with local art historian and archaeologist Maria Cristina Carile, I was able to attend the opening of the Archaeological Park of Classe (Parco Archaeologico di Classe) (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Poster for Parco Archaeologico di Classe, opening events summer 2015.

After viewing a brief video about the history of the site, visitors are able to walk along a path leading through the site. Illuminated at night, foundations of storage magazines in the port are visible, and reconstruction drawings printed on glass panels allow for an impression of the buildings as they may have stood (Figures 10 and 11). Due to summer heat, the site is only open in the evenings, but will be accessible during the day as of September 1.

Figure 10: Parco Archaeologico di Classe, view of site from visitor center (P. Blessing)

Figure 11: Parco Archaeologico di Classe, informative panel with architectural reconstruction (P. Blessing)

Further down the road stands the basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe, another sixth-century monument with rich mosaic decoration (Figure 12). With this, I take leave from Ravenna to move on to Croatia.

Figure 12: Sant’Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna, view towards apse (P. Blessing)

From Ravenna, by train and bus, I travelled to Poreč, a seaside town that is brimming with visitors in the summer months, many of them attracted by the beaches and islands of Istria. The promenade along the peninsula where the old town is located features both remains of city-walls and late nineteenth-century villas and hotels (Figure 13). My main reason for visiting, however, was the Euphrasian Basilica and nearby episcopal palace (Figure 14). Originally built in the fourth century, the basilica received its current form and rich mosaic decoration (Figure 15) in the sixth century, during the tenure of bishop Euphrasisus. The palace was the residence of the bishop for Poreč

for over 1300 years. Conservation and restoration program begun in 1989 when bishop’s residence and offices were moved to a new building nearby.2

Figure 13: Poreč, promenade along the old town (P. Blessing)

Figure 14: Euphrasian Basilica, Poreč, interior towards apse (P. Blessing)

Henry Maguire and Ann Terry studied the mosaics were studied in detail beginning in 1997; one major difficulty was to determine the extent of several nineteenth-century restoration campaigns.3 As I was sitting in the basilica during a piano concert and recital that I had happened upon, I could not help admiring both the structure, and the gleaming gold of the mosaics, effective even with electric lighting, and think what the basilica would have looked like 1500 years ago.

Figure 15: Euphrasian Basilica, Poreč, detail of sixth-century apse mosaic and thirteenth-century ciborium (P. Blessing)

Jäggi, Carola. Ravenna: Kunst und Kultur einer spätantiken Residenzstadt: Die Bauten Und Mosaiken des 5. und 6. Jahrhunderts. Regensburg: Schnell Steiner, 2013.

Matejčić, Ivan. “The episcopal palace at Poreč: results of recent excavation and restauration,” Hortus Artium Medievalium 1 (1995): 84-89.

Prelog, Milan. The Basilica of Euphrasius in Poreč. Zagreb: Associated Publishers, 1986.

Terry, Ann and Henry Maguire. Dynamic Splendor: The Wall Mosaics in the Cathedral of Euphrasius in Porec, University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007.

Terry, Ann and Henry Maguire, “The Wall Mosaics of the Cathedral of Eufrasius in Poreč: Third Preliminary Report,” Hortus Artium Medievalium 7 (2001): 131-166.

Terry, Ann and Henry Maguire, “The Wall Mosaics of the Cathedral of Eufrasius in Poreč: Second Preliminary Report,” Hortus Artium Medievalium 6 (2000): 159-182.

Terry, Ann and Fiona Gilmore Eaves. A Century of Archaeology at Poreč (1847–1947), Zagreb: University of Zagreb, 2001.

Figure 1: San Vitale, Ravenna, view (P. Blessing)

Visiting Ravenna, I move around the city and its major monuments with a fresh eye. The first stop is the sixth-century church of San Vitale (Figure 1). Inside church, the mosaic decoration has been preserved in the apse, but not in the dome (Figure 2).

Figure 2: San Vitale, Ravenna, part of apse mosaic (left) and 18th-century paintings inside the dome (right)

In both sides of the apse, mosaics show, to the left, the court of Byzantine emperor Justinian (r. 527–565) and, to the right, of his wife Theodora. Accompanying Justinian, we see bishop Maximianus during whose tenure (546–556) the basilica, commissioned by his predecessor Victor in 528, was completed (Figure 3). A detail of the court of empress Theodora shows the elaborate dresses and jewels with which both men and women of the court were represented (Figure 4).

Figure 3: San Vitale, Ravenna, mosaic showing Justinian’s court (P. Blessing)

Figure 4: San Vitale, Ravenna, mosaic showing detail of Theodora’s court; the empress is shown at far left (P. Blessing)

The next stop, just behind San Vitale, is the mausoleum of Galla Placidia (Figure 5), a small structure that houses another example of the splendid mosaics that Ravenna is famous for, although this is even earlier than San Vitale. The mausoleum was built for Galla Placidia, a sister of Roman emperor Honorius who moved his capital to Ravenna. According to local lore, she died in Ravenna in 452 and her sarcophagus was placed in the small structure, under a mosaic sky with gold stars (Figure 6).

Figure 5: Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Ravenna, view (P. Blessing)

Figure 6: Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, interior view of dome (P. Blessing)

At the basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, mosaics extend along the upper section of the central nave and into the apse. Begun in 493, construction of the church now dedicated to Ravenna’s patron continued into the early sixth century. The initial dedication to the Saviour was not changed until the early sixteenth century. Most notable—at least for historians of architecture— are the two representations of monuments that are included in these monuments. The first, to the right as one enters the church at its western end, is a symbolically complex representation of an imperial palace, one of many found in late antique and Byzantine art.1 Clearly labeled “Palatium” (palace, in Latin), the structure has open doors and windows with curtains flying in a light breeze (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Detail of mosaics in Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, showing palace (P. Blessing)

Figure 8: Detail of mosaics in Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, showing harbor of Classe (P. Blessing)

Facing the representation of the palace is one of a fortified city and harbor (Figure 8). Shown here is the harbor of Classe, near Ravenna. Even though it is no longer directly on the sea nowadays due to changes in water levels and silting, Ravenna and its port of Classe were important naval bases in the fifth and sixth centuries. The port of Classe, a 15-minute drive from central Ravenna, is a major archaeological site. Together with local art historian and archaeologist Maria Cristina Carile, I was able to attend the opening of the Archaeological Park of Classe (Parco Archaeologico di Classe) (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Poster for Parco Archaeologico di Classe, opening events summer 2015.

After viewing a brief video about the history of the site, visitors are able to walk along a path leading through the site. Illuminated at night, foundations of storage magazines in the port are visible, and reconstruction drawings printed on glass panels allow for an impression of the buildings as they may have stood (Figures 10 and 11). Due to summer heat, the site is only open in the evenings, but will be accessible during the day as of September 1.

Figure 10: Parco Archaeologico di Classe, view of site from visitor center (P. Blessing)

Figure 11: Parco Archaeologico di Classe, informative panel with architectural reconstruction (P. Blessing)

Further down the road stands the basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe, another sixth-century monument with rich mosaic decoration (Figure 12). With this, I take leave from Ravenna to move on to Croatia.

Figure 12: Sant’Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna, view towards apse (P. Blessing)

From Ravenna, by train and bus, I travelled to Poreč, a seaside town that is brimming with visitors in the summer months, many of them attracted by the beaches and islands of Istria. The promenade along the peninsula where the old town is located features both remains of city-walls and late nineteenth-century villas and hotels (Figure 13). My main reason for visiting, however, was the Euphrasian Basilica and nearby episcopal palace (Figure 14). Originally built in the fourth century, the basilica received its current form and rich mosaic decoration (Figure 15) in the sixth century, during the tenure of bishop Euphrasisus. The palace was the residence of the bishop for Poreč

for over 1300 years. Conservation and restoration program begun in 1989 when bishop’s residence and offices were moved to a new building nearby.2

Figure 13: Poreč, promenade along the old town (P. Blessing)

Figure 14: Euphrasian Basilica, Poreč, interior towards apse (P. Blessing)

Henry Maguire and Ann Terry studied the mosaics were studied in detail beginning in 1997; one major difficulty was to determine the extent of several nineteenth-century restoration campaigns.3 As I was sitting in the basilica during a piano concert and recital that I had happened upon, I could not help admiring both the structure, and the gleaming gold of the mosaics, effective even with electric lighting, and think what the basilica would have looked like 1500 years ago.

Figure 15: Euphrasian Basilica, Poreč, detail of sixth-century apse mosaic and thirteenth-century ciborium (P. Blessing)

Selected Bibliography

Carile, Maria Cristina. The Vision of the Palace of the Byzantine Emperors as a Heavenly Jerusalem. Studi e ricerche di archeologia e storia dell'art, 12. Spoleto: Fondazione Centro Italiano di Studi sull'alto Medioevo, 2012.Jäggi, Carola. Ravenna: Kunst und Kultur einer spätantiken Residenzstadt: Die Bauten Und Mosaiken des 5. und 6. Jahrhunderts. Regensburg: Schnell Steiner, 2013.

Matejčić, Ivan. “The episcopal palace at Poreč: results of recent excavation and restauration,” Hortus Artium Medievalium 1 (1995): 84-89.

Prelog, Milan. The Basilica of Euphrasius in Poreč. Zagreb: Associated Publishers, 1986.

Terry, Ann and Henry Maguire. Dynamic Splendor: The Wall Mosaics in the Cathedral of Euphrasius in Porec, University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007.

Terry, Ann and Henry Maguire, “The Wall Mosaics of the Cathedral of Eufrasius in Poreč: Third Preliminary Report,” Hortus Artium Medievalium 7 (2001): 131-166.

Terry, Ann and Henry Maguire, “The Wall Mosaics of the Cathedral of Eufrasius in Poreč: Second Preliminary Report,” Hortus Artium Medievalium 6 (2000): 159-182.

Terry, Ann and Fiona Gilmore Eaves. A Century of Archaeology at Poreč (1847–1947), Zagreb: University of Zagreb, 2001.

- See Carile, The Vision of the Palace.

- Matejčić, “The Episcopal Palace at Poreč,” 84-85.

- Terry and Maguire, “The Wall Mosaics of the Cathedral of Eufrasius,” 159-162.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top