-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Monuments of Balkan Empires: Ottoman and Habsburg Architecture in Zagreb, Sarajevo and Mostar

I begin where I left off in my first post a month ago, in the city of Poreč in Croatia, where both fifth-century Byzantine and nineteenth-century Italian heritage are present. The theme of this post is the architectural presence of two of the empires that, over the last 1600 years, have ruled in the Balkans. The conflicted history of the region is particularly present this year, in 2015, with the 20th Anniversary of major events during the Yugoslav wars—most importantly the massacre of Srebrenica (now in Bosnia-Hercegovina) in July 1995. I will return to this point below, in my report on Bosnia’s capital Sarajevo. The anniversary of the beginning of World War I last summer also returned the city to the center of worldwide media attention.

From Poreč, my journey took me to Zagreb, the capital of Croatia. The city center, near the main train station, is dominated by the nineteenth-century architecture of the Austro-Hungarian Habsburg Empire. Buildings such as the current home of the Archaeological Museum are part of the monumental aspect of the city in this period (Figures 1 and 2), but also show intricate details such as the stairwell decoration within the museum. Originally the city palace of Baron Dragutin Vranyczany, the building was completed in 1880 and opened as a museum after World War I.1

Figure 1: Detail, Façade of Archaeological Museum, Zagreb (P. Blessing)

Figure 2: Detail of stairwell decoration, Archaeological Museum, Zagreb (P. Blessing)

Figure 3: St. Mark’s Church, Zagreb (P. Blessing)

In the upper part of the city, the colorful roof of the thirteenth-century St. Mark’s Church (Figure 3) stands out against the sky. More familiar, yet quite similar in its aspect, is the roof of St. Stephen’s cathedral in Vienna, a fourteenth century construction restored in 1831, yet several late 19th- and early 20th-century examples exist within the former Habsburg possessions in the Balkans. According to architectural historian Dragan Damjanović: “These distinctive roofs became symbols of the places and the times in which they were built, and in Croatia and elsewhere, the bright tiles often reflected nationalist aspirations.”2 Effectively, these monuments became symbolic of the cultural development and growing national consciousness in late 19th-century Croatia, but were also part of an increased interest in medieval architecture, as Damjanović further explains. In the 1870s, architect Friedrich Schmidt was commissioned with the restoration of St. Mark’s Church, where he subsequently created the current, multicolored roof that specifically expressed Croatian identity.3 At the same time, the roof project also engaged in contemporary discussions about the revival of folk art, in that traditional embroidery and weaving patterns served as model for some of the motives used on the roof. This aspect of the project also connected it to architect Gottfried Semper’s argument of textiles as Urkunst that was current at the time.4 Overall, the restoration of the roof was symptomatic of Croatia’s position within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and of the discussions in architecture and design in this period. Nevertheless, the architecture of the period was not exclusively historicist, as buildings such as the Archaeological Museum or the bank building shown in (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Bank in Zagreb’s city center (P. Blessing)

Some aspects of the architecture seen in Zagreb also apply in Sarajevo, capital of Bosnia-Hercegovina, yet differences in historical context create major differences. Seen from the top of the citadel hill, Sarajevo today is a combination of the old Ottoman town, Habsburg architecture, Communist era buildings, and newly built skyscrapers and shopping malls (Figure 5).

Figure 5: view of central Sarajevo, with old town at the center of the image (P. Blessing)

Even in this overall view, the Ottoman past of Sarajevo is visible in the domes and minarets of several mosques. Most well known are the Gazi Hüsrevbeg Mosque and its adjacent monuments—extant parts of the complex include two mausolea, a madrasa, and a bedesten (marketplace). Founded in 1531 by Gazi Hüsrev Bey (d. 1541), then the Ottoman governor of Bosnia, it is dominates the old Ottoman center of Sarajevo (Figures 6, 7, 8). The mosque was badly damaged during the war and restored in 1996–97.

Figure 6: Dome and minaret of the Gazi Hüsrevbeg Mosque (P. Blessing)

Figure 7: Roof of the Gazi Hüsrevbeg Madrasa (P. Blessing)

Figure 8: Bedesten, part of Gazi Hüsrevbeg Complex (P. Blessing)

Next to the madrasa stands the new building of the Gazi Hüsrev Begova Library; even though large parts of the collection were destroyed during the siege of Sarajevo in the 1990s, it still houses an important collection of Ottoman archival documents and manuscripts, including the collection that belonged to the mosque complex and is an essential resource for scholars.

Walking from the Gazi Hüsrevbeg Complex through the old town to the Miljecka river, one observes numerous restaurants, cafés, and souvenir shops in an area frequented by tourists and locals alike. On the waterfront own both sides of the river, nineteenth-century monuments predominate; one of the most striking ones is the Sarajevo City Hall or Vijećnica (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Vijećnica, Sarajevo, view (P. Blessing)

The building immediately strikes the viewer with its architecture, inspired by an eclectic array of medieval Islamic monuments, ranging from the eleventh-century Fatimid mosques of Cairo to the fourteenth-century Alhambra in Granada. Built in as the city hall 1892–94 based on a project by Austrian architect Alexander Wittek, it is a monumental testimony to late-nineteenth-century interest in Islamic architecture. (For the Ottoman historians among the readers: if anyone knows whether the architect is in anyway related to Paul Wittek, I would love to know). The building is perhaps symptomatic of the Habsburg Empire’s struggles to integrate a region with a predominantly Muslim population, after it had occupied Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1878.

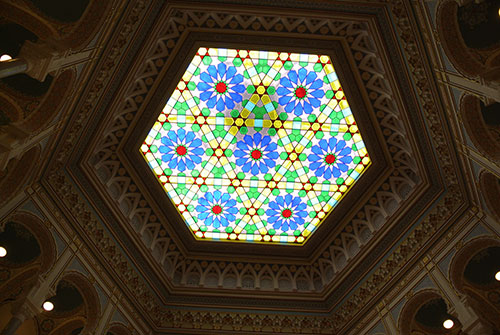

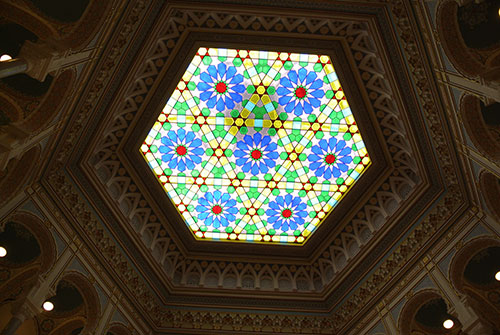

Figure 10: Vijećnica, Sarajevo, staircase (P. Blessing)

Figure 11: Vijećnica, Sarajevo, stained glass over central courtyard (P. Blessing)

In 1949, the building became the National and University Library, a function it still helf when it burned down after being shelled by Serbian forces in 1992; nearly 2 million books were destroyed. The building was meticulously restored and reopened to the public in 2014. For a timeline and photos of the construction and restoration until 2008, please visit http://vijecnica.ba/.

In the interior (Figures 10 and 11) the building is a combination of various elements that are inspired by Islamic architecture, but in no way related to the Ottoman monuments in Sarajevo or elsewhere in the Balkans. To what extent this was a deliberate rejection of the Ottoman heritage of a region now under Hapsburg rule is question that I plan to explore further. Monuments using similar stylistic elements are found elsewhere in the city, along with other elements that might be deemed Orientalist, such as a the figures in Ottoman and local costumes (Figure 12) on a 1902 building along Obala Maršala Tita.

Figure 12: Detail of decoration on a residential building Obala Maršala Tita, Sarajevo (P. Blessing)

Continuing along the same street, which leads from the historical center towards the train station, the visitor stops before a striking glass structure (Figure 13), the monument to children killed during the siege of Sarajevo. This is only one of the many reminders of the war that are still present in Sarajevo, together with ruined buildings bullet holes on facades. The monument is one of the many signs of the inescapable reality of death in the city—the Ottoman gravestones in the park behind the monument (Figure 14) are another one.

Figure 13: monument to children killed during the siege of Sarajevo, Veliki Park, Sarajevo (P. Blessing)

Figure 14: Ottoman grave stones in Veliki Park, Sarajevo (P. Blessing)

Many others of these grave markers are found in the cemeteries around the Ottoman mosques of Sarajevo, where they are joined by new burials often from the Yugoslav wars. One example is the cemetery of the Ali Pasha Mosque (1560–61), a building that is one of the many marks of the Ottoman past of Sarajevo (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Ali Pasha Mosque and cemetery, Sarajevo (P. Blessing)

Despite the presence of these cemeteries throughout the city center, nothing prepared me for the cemeteries on the slopes of Kovači, between the old town and old citadel (Figures 16 and 17). Here, on Ottoman cemeteries going back to the fifteenth centuries, graves of those killed during the war in 1992-95 cover large areas in a site that also serves as a war memorial. In a central position, the tomb of Alija Izetbegović (1925–2003), the first president of Bosnia from its independence in 1992 until 2000, is covered by an open dome (visible at the left of figure 17).

Figures 16 and 17: cemeteries, Kovači, Sarajevo (P. Blessing)

These cemeteries are among the sites that leave the visitor unsettled, and I have certainly grappled whether to include photographs of the graves. The easy way out of course would have been to say that the cemeteries are not strictly speaking architecture, and hence not closely related to the theme of my fellowship and travels. I decided against this excuse since it is impossible to visit Sarajevo today without encountering reminders of its painful past.

Figure 18: Old Bridge (Stari Most), Mostar (P. Blessing)

The same was true in Mostar, where the famous sixteenth-century Old Bridge over the Neretva river (Figure 18) is the central monument to be viewed. The site is a major tourist attraction offered as a daytrip for the vacationers on Croatia’s beaches, some of them less than 100km away. Destroyed in 1992 during fighting between Croats and Bosnians, the bridge was completely rebuilt and completed in 2004. The arch, built by a pupil of sixteenth-century architect Sinan, is one of the masterpieces of Ottoman architecture (Figure 19). At the same time, other monuments in the old town were reconstructed as part of a major project involving the World Monuments Fund and the Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

Figure 19: detail of arch, Old Bridge (Stari Most), Mostar (P. Blessing)

Also damaged in the war and subsequently restored was the Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque (Figure 20), built in 1618. Located at very edge of the cliff above the river, the mosque is best viewed from the Old Bridge, and itself offers a great perspective on the latter.

Figure 20: Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque, Mostar (P. Blessing)

Nearby, the Karadjoz Beg Mosque, built in 1557 (Figures 21 and 22) was also restored, although other sites in the city still need to be completed; it is here that I take leave from the reader with much still to think about.

Figures 21 and 22: Karadjoz Beg Mosque, Mostar (P. Blessing)

Damjanović, Dragan, “Polychrome Roof Tiles and National Style in Nineteenth-century Croatia,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 70, No. 4 (December 2011), pp. 466–491, accessed 27 June 2015.

Donia, Robert J. Sarajevo, A biography (London: Hurst & Co., 2006)

Eren, Halit, Amir Pašić and Aida Idrizbegović Zgonić, Restoration of Mosques in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Istanbul: IRCICA, 2013)

Kreševljaković, Hamdija. Sarajevo Za Vrijeme Austrougarske Uprave (1878–1918) (Sarajevo: Arhiv Grada, 1969), English abstract in: Aptin Khanbaghi (ed.) Cities as Built and Lived Environments: Scholarship from Muslim Contexts, 1875 to 2011 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University in Association with The Aga Khan University, Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations, 2014), p. 115.

From Poreč, my journey took me to Zagreb, the capital of Croatia. The city center, near the main train station, is dominated by the nineteenth-century architecture of the Austro-Hungarian Habsburg Empire. Buildings such as the current home of the Archaeological Museum are part of the monumental aspect of the city in this period (Figures 1 and 2), but also show intricate details such as the stairwell decoration within the museum. Originally the city palace of Baron Dragutin Vranyczany, the building was completed in 1880 and opened as a museum after World War I.1

Figure 1: Detail, Façade of Archaeological Museum, Zagreb (P. Blessing)

Figure 2: Detail of stairwell decoration, Archaeological Museum, Zagreb (P. Blessing)

Figure 3: St. Mark’s Church, Zagreb (P. Blessing)

In the upper part of the city, the colorful roof of the thirteenth-century St. Mark’s Church (Figure 3) stands out against the sky. More familiar, yet quite similar in its aspect, is the roof of St. Stephen’s cathedral in Vienna, a fourteenth century construction restored in 1831, yet several late 19th- and early 20th-century examples exist within the former Habsburg possessions in the Balkans. According to architectural historian Dragan Damjanović: “These distinctive roofs became symbols of the places and the times in which they were built, and in Croatia and elsewhere, the bright tiles often reflected nationalist aspirations.”2 Effectively, these monuments became symbolic of the cultural development and growing national consciousness in late 19th-century Croatia, but were also part of an increased interest in medieval architecture, as Damjanović further explains. In the 1870s, architect Friedrich Schmidt was commissioned with the restoration of St. Mark’s Church, where he subsequently created the current, multicolored roof that specifically expressed Croatian identity.3 At the same time, the roof project also engaged in contemporary discussions about the revival of folk art, in that traditional embroidery and weaving patterns served as model for some of the motives used on the roof. This aspect of the project also connected it to architect Gottfried Semper’s argument of textiles as Urkunst that was current at the time.4 Overall, the restoration of the roof was symptomatic of Croatia’s position within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and of the discussions in architecture and design in this period. Nevertheless, the architecture of the period was not exclusively historicist, as buildings such as the Archaeological Museum or the bank building shown in (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Bank in Zagreb’s city center (P. Blessing)

Some aspects of the architecture seen in Zagreb also apply in Sarajevo, capital of Bosnia-Hercegovina, yet differences in historical context create major differences. Seen from the top of the citadel hill, Sarajevo today is a combination of the old Ottoman town, Habsburg architecture, Communist era buildings, and newly built skyscrapers and shopping malls (Figure 5).

Figure 5: view of central Sarajevo, with old town at the center of the image (P. Blessing)

Even in this overall view, the Ottoman past of Sarajevo is visible in the domes and minarets of several mosques. Most well known are the Gazi Hüsrevbeg Mosque and its adjacent monuments—extant parts of the complex include two mausolea, a madrasa, and a bedesten (marketplace). Founded in 1531 by Gazi Hüsrev Bey (d. 1541), then the Ottoman governor of Bosnia, it is dominates the old Ottoman center of Sarajevo (Figures 6, 7, 8). The mosque was badly damaged during the war and restored in 1996–97.

Figure 6: Dome and minaret of the Gazi Hüsrevbeg Mosque (P. Blessing)

Figure 7: Roof of the Gazi Hüsrevbeg Madrasa (P. Blessing)

Figure 8: Bedesten, part of Gazi Hüsrevbeg Complex (P. Blessing)

Next to the madrasa stands the new building of the Gazi Hüsrev Begova Library; even though large parts of the collection were destroyed during the siege of Sarajevo in the 1990s, it still houses an important collection of Ottoman archival documents and manuscripts, including the collection that belonged to the mosque complex and is an essential resource for scholars.

Walking from the Gazi Hüsrevbeg Complex through the old town to the Miljecka river, one observes numerous restaurants, cafés, and souvenir shops in an area frequented by tourists and locals alike. On the waterfront own both sides of the river, nineteenth-century monuments predominate; one of the most striking ones is the Sarajevo City Hall or Vijećnica (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Vijećnica, Sarajevo, view (P. Blessing)

The building immediately strikes the viewer with its architecture, inspired by an eclectic array of medieval Islamic monuments, ranging from the eleventh-century Fatimid mosques of Cairo to the fourteenth-century Alhambra in Granada. Built in as the city hall 1892–94 based on a project by Austrian architect Alexander Wittek, it is a monumental testimony to late-nineteenth-century interest in Islamic architecture. (For the Ottoman historians among the readers: if anyone knows whether the architect is in anyway related to Paul Wittek, I would love to know). The building is perhaps symptomatic of the Habsburg Empire’s struggles to integrate a region with a predominantly Muslim population, after it had occupied Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1878.

Figure 10: Vijećnica, Sarajevo, staircase (P. Blessing)

Figure 11: Vijećnica, Sarajevo, stained glass over central courtyard (P. Blessing)

In 1949, the building became the National and University Library, a function it still helf when it burned down after being shelled by Serbian forces in 1992; nearly 2 million books were destroyed. The building was meticulously restored and reopened to the public in 2014. For a timeline and photos of the construction and restoration until 2008, please visit http://vijecnica.ba/.

In the interior (Figures 10 and 11) the building is a combination of various elements that are inspired by Islamic architecture, but in no way related to the Ottoman monuments in Sarajevo or elsewhere in the Balkans. To what extent this was a deliberate rejection of the Ottoman heritage of a region now under Hapsburg rule is question that I plan to explore further. Monuments using similar stylistic elements are found elsewhere in the city, along with other elements that might be deemed Orientalist, such as a the figures in Ottoman and local costumes (Figure 12) on a 1902 building along Obala Maršala Tita.

Figure 12: Detail of decoration on a residential building Obala Maršala Tita, Sarajevo (P. Blessing)

Continuing along the same street, which leads from the historical center towards the train station, the visitor stops before a striking glass structure (Figure 13), the monument to children killed during the siege of Sarajevo. This is only one of the many reminders of the war that are still present in Sarajevo, together with ruined buildings bullet holes on facades. The monument is one of the many signs of the inescapable reality of death in the city—the Ottoman gravestones in the park behind the monument (Figure 14) are another one.

Figure 13: monument to children killed during the siege of Sarajevo, Veliki Park, Sarajevo (P. Blessing)

Figure 14: Ottoman grave stones in Veliki Park, Sarajevo (P. Blessing)

Many others of these grave markers are found in the cemeteries around the Ottoman mosques of Sarajevo, where they are joined by new burials often from the Yugoslav wars. One example is the cemetery of the Ali Pasha Mosque (1560–61), a building that is one of the many marks of the Ottoman past of Sarajevo (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Ali Pasha Mosque and cemetery, Sarajevo (P. Blessing)

Despite the presence of these cemeteries throughout the city center, nothing prepared me for the cemeteries on the slopes of Kovači, between the old town and old citadel (Figures 16 and 17). Here, on Ottoman cemeteries going back to the fifteenth centuries, graves of those killed during the war in 1992-95 cover large areas in a site that also serves as a war memorial. In a central position, the tomb of Alija Izetbegović (1925–2003), the first president of Bosnia from its independence in 1992 until 2000, is covered by an open dome (visible at the left of figure 17).

Figures 16 and 17: cemeteries, Kovači, Sarajevo (P. Blessing)

These cemeteries are among the sites that leave the visitor unsettled, and I have certainly grappled whether to include photographs of the graves. The easy way out of course would have been to say that the cemeteries are not strictly speaking architecture, and hence not closely related to the theme of my fellowship and travels. I decided against this excuse since it is impossible to visit Sarajevo today without encountering reminders of its painful past.

Figure 18: Old Bridge (Stari Most), Mostar (P. Blessing)

The same was true in Mostar, where the famous sixteenth-century Old Bridge over the Neretva river (Figure 18) is the central monument to be viewed. The site is a major tourist attraction offered as a daytrip for the vacationers on Croatia’s beaches, some of them less than 100km away. Destroyed in 1992 during fighting between Croats and Bosnians, the bridge was completely rebuilt and completed in 2004. The arch, built by a pupil of sixteenth-century architect Sinan, is one of the masterpieces of Ottoman architecture (Figure 19). At the same time, other monuments in the old town were reconstructed as part of a major project involving the World Monuments Fund and the Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

Figure 19: detail of arch, Old Bridge (Stari Most), Mostar (P. Blessing)

Also damaged in the war and subsequently restored was the Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque (Figure 20), built in 1618. Located at very edge of the cliff above the river, the mosque is best viewed from the Old Bridge, and itself offers a great perspective on the latter.

Figure 20: Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque, Mostar (P. Blessing)

Nearby, the Karadjoz Beg Mosque, built in 1557 (Figures 21 and 22) was also restored, although other sites in the city still need to be completed; it is here that I take leave from the reader with much still to think about.

Figures 21 and 22: Karadjoz Beg Mosque, Mostar (P. Blessing)

Selected Bibliography

Damjanović, Dragan, “Polychrome Roof Tiles and National Style in Nineteenth-century Croatia,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 70, No. 4 (December 2011), pp. 466–491, accessed 27 June 2015.

Donia, Robert J. Sarajevo, A biography (London: Hurst & Co., 2006)

Eren, Halit, Amir Pašić and Aida Idrizbegović Zgonić, Restoration of Mosques in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Istanbul: IRCICA, 2013)

Kreševljaković, Hamdija. Sarajevo Za Vrijeme Austrougarske Uprave (1878–1918) (Sarajevo: Arhiv Grada, 1969), English abstract in: Aptin Khanbaghi (ed.) Cities as Built and Lived Environments: Scholarship from Muslim Contexts, 1875 to 2011 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University in Association with The Aga Khan University, Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations, 2014), p. 115.

- “U Arheološkom muzeju otvorena izložba ''i Palača i Muzej,” accessed 26 August 2015.

- Damjanović, “Polychrome Roof Tiles,” 467.

- Damjanović, “Polychrome Roof Tiles,” 472–76.

- Damjanović, “Polychrome Roof Tiles,” 476–78.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top