-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Mirrors of the Orient: Exhibitions of Islamic Art in Europe

As the year winds down, I would like to take the opportunity to write about a number of museum collections that I have visited since my travels began in July. Specifically, I would like to discuss exhibitions of Islamic art within Europe, several of which have been rearranged in the last few years. Considering the political situation in much of the Middle East, museum collections are becoming more and more important as resources for research and preservation. As for any type of research project that relies on fieldwork, studies of architectural history are strongly affected by conditions of travel, and places that can no longer be visited risk moving to the margins of research. This in turn is a major issue when sites are subsequently destroyed—consider the twelfth-century minaret of the Umayyad Mosque of Aleppo, reduced to a pile of rubble in spring 2013, and the historical covered market of the same city. Initiatives to document monuments have begun to emerge; they include UT Antiquities Action, yet it is hard to image what could be rebuilt if the war in Syria were to end.

Over the last ten years, several collections of Islamic art in major collections around the globe received new displays; these include the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Louvre in Paris, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, and the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art in Istanbul that I will discuss in my next post. The Museum for Islamic Art in Berlin is scheduled to move to a new space within the larger renovation project of the Museum Island and particularly the Pergamon Museum, to be completed by 2025. Admittedly, I have not yet had a chance to visit the David Collection in Copenhagen, which has a strong focus on Islamic art. New museums, such as the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, opened in 2014, have sprung up as well. At the same time, collections containing large numbers of Islamic objects, such as that of the Musée des Tissus in Lyon, France, are at peril: the museum may close if new options for funding are not found. In this context, the dynamic world of museum collections is closely tied to politics, both at the level of spending cuts for culture, and in the connection to the antiques trade and preservation of cultural heritage from conflict regions.

Today, I will focus on collections in Italy, France, and the United Kingdom that I visited in the last few months. Of the collections mentioned above, I am also familiar with the Metropolitan Museum and the Berlin collection. The latter is left out here, because it will reinstalled at a later point; I would, however, like to point to the excellent special exhibition about former director and historian of Islamic art, Friedrich Sarre (1865–1945), on view until January 24, 2016. As I visited the exhibits and later discussed some of them with colleagues, I became more and more aware of the biases of an art historian inherent in my view on these displays. Thus, I find it hard to assess the view of the general public going into the galleries without prior knowledge of Islamic art, and can’t help looking out for the major pieces I know to be located in each collection.

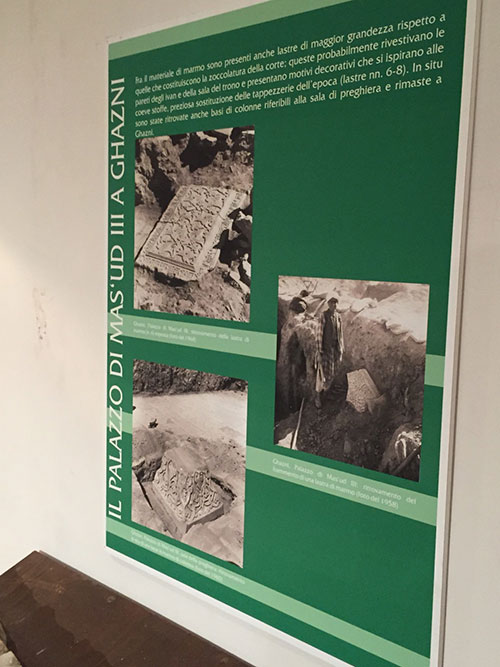

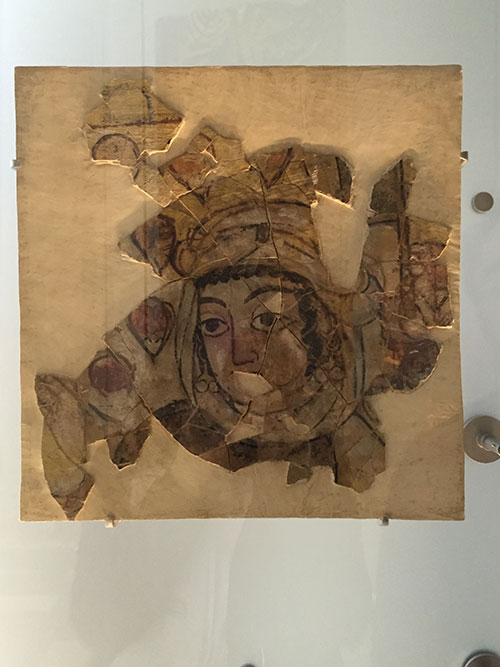

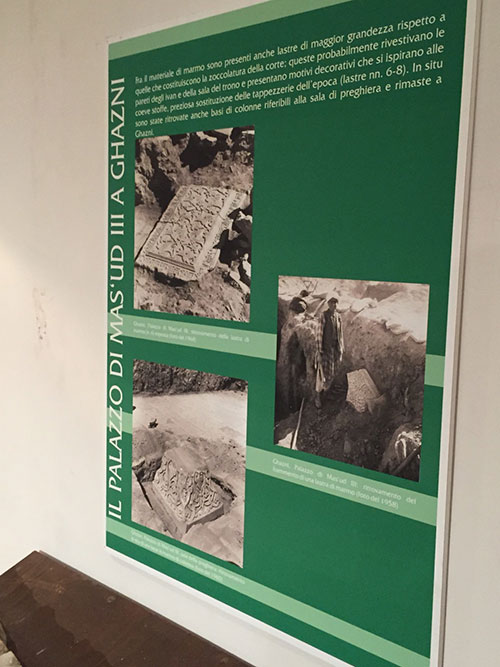

This summer, in Rome, I visited for the first time the Museo Nazionale d’Arte Orientale, home to one of the largest collections of Islamic art in Italy. Within this collection, a main focus are objects from the excavations at Ghazni, Afghanistan, the capital of the Ghaznavid dynasty that ruled over present-day Afghanistan, north-eastern Iran, and northern India from the late tenth to the mid-twelfth centuries. Excavations at the sites were conducted by the now-defunct Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente (ISIAO) in the late 1950s and the 1960s (Figure 1). The excavations mostly investigated the palace of Ghaznavid sultan Masud III (r. 1099–1115); major finds include carved marble panels that served as wall decoration (Figure 2). Overall, the collection unfortunately remains on the margins of Rome’s museum circuit, with its masses of visitors streaming into sites such as the Vatican Museums, but bypassing other exhibits such as this. In addition to Islamic art, the collection also has a strong focus on East Asia, including China, Japan, and Korea; the building itself is worth a visit, too (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Panel describing the history of the Ghazni excavations, Museo Nazionale d’Arte Orientale, Rome (P. Blessing)

Figure 2: Detail of marble panel from the Ghazni excavations, Museo Nazionale d’Arte Orientale, Rome (P. Blessing)

Figure 3: Nineteenth-century chandelier, Museo Nazionale d’Arte Orientale, Rome (P. Blessing)

Walking through Rome, I came across numerous posters of another exhibition (Figure 4). Objects from the al-Sabah collection of Islamic art, based in the Dar al-Athar al-Islamiyya in Kuwait, happened to be in view in the Scuderie del Quirinale. This traveling exhibition was a chance to see objects that are not often easily accessible; even though photography was not permitted in the show, some of the objects and others from the collection can be viewed on the Google Art Project, although item information on the site, unfortunately, is very limited.

Figure 4: Poster for the exhibition of the al-Sabah collection in Rome (P. Blessing)

Figure 5: Roof over Islamic galleries, Louvre, Paris, seen from above (P. Blessing)

Figure 6: Upper floor of Islamic galleries, Louvre, Paris, with eleventh-century stucco inscription frieze from Saveh, Iran (P. Blessing)

Moving on to Paris, the Louvre opened its new permanent exhibition of Islamic art in fall 2012. A courtyard received a new roof (Figure 5), and two floors of exhibition space were built into it (Figure 6). The space is a first rather overwhelming, and one needs several visits to form a better view of the exhibit. On the upper floor, seen in figure 6, light flows through the roof structure while the lower floor is quite dark. The narrative is largely chronological, beginning with early Islam on the first floor. Thematic cases include the role of calligraphy in Islamic art and the influence of Chinese ceramics on the early Islamic production. Pieces from major sites such as the ninth-century Abbasid palaces of Samarra, and well-known objects such as the tenth-century ivory pyxis of Mughira from Umayyad Spain are shown alongside extensive exhibits from the site of Siraf on the Persian Gulf, including ceramics influenced by Chinese examples. The lower level is harder to navigate, as the trajectory is not quite clear from the start. In effect, it is largely chronological, with the continuation of the medieval exhibits in the room at the far end, and the early modern display—the collection ends at 1800—in the center. Coming down the stairs from the upper floor, however, the visitor is not clearly guided in one or the other direction. The cases with book paintings, placed quite understandably in a little-lit spot, are unfortunately easy to miss due to their location underneath the stairs. Other displays, however, are well presented, such as the selection of images of royal figures on ceramics. A fifteenth-century Mamluk stone porch, taken to Paris from Cairo for the 1889 World Fair and not on view for over a century, was restored and reassembled for the new display as an instructive video explains. Overall, several short videos about production processes—of, for instance, ceramics and inlaid metalwork—are worth the time for their simple and well-designed explanations of techniques. Additionally, replicas of several objects are available to touch. While these displays, featuring labels in Braille writing, are primarily intended for visitors with impaired vision, they are attractive for all. Although the pieces are all made of the same material and don’t provide a sense of texture, small samples of materials are added for that purpose.

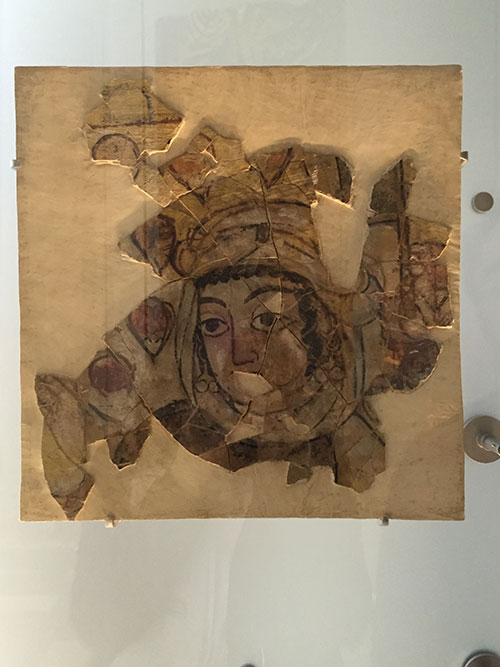

The Institut du Monde Arabe, research center, library and museum all in one has a permanent exhibit focusing on Islamic art. The narrative here, rather than focusing on the historical trajectory of dynasties, revolves around themes such as medicine and astronomy, in addition to some chronological displays. Highlights are fragments of wall-paintings (Figure 7) from the seventh-century desert castle of Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi in Syria, and pieces of mosaic from the Great Mosque of Damascus, on loan from the National Museum in Damascus. While it is wonderful to see these objects in Paris, this does little to distract from the fact that both monuments and the large number of finds from Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi in Syria are out of reach. In a recent interview with Swiss newspaper Der Bund, Mohamed Fakhro, deputy director of the National Museum in Aleppo and now living in Germany where he pursues research, pointed out the extent to which the destruction of cultural heritage adds to the human suffering caused by the conflict.

Figure 7: Fragment of wall painting from Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi, Syria, on loan to the Institut to Monde Arabe, Paris (P. Blessing)

In the UK, several museums have new displays of Islamic art, while the British Museum recently announced that new Islamic galleries would open in 2018. The Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London opened its Jameel Gallery of Islamic Art in 2008 (Figure 8). The center of the room is dominated by the Ardabil carpet, a very large (10.51m x 5.34m) sixteenth-century piece that comes from the ancestral shrine of the Safavid dynasty in northern Iran. The other exhibits are arranged around the room, both along the walls (Figure 9) and in cases that separate the central space from the circuit around.

Figure 8: Jameel Gallery of Islamic Art, Victoria and Albert Museum, London (P. Blessing)

Figure 9: Tiles in carved terracotta technique from tomb of Buyanquli Khan, Bukhara, Uzbekistan, built in 1358; preserved at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (P. Blessing)

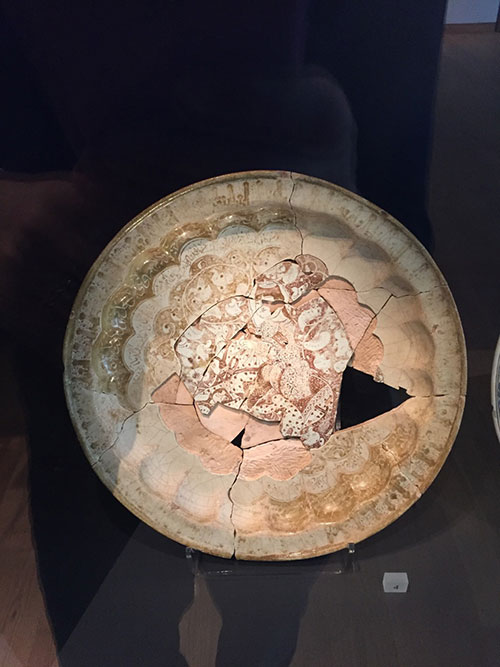

The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, in its current state, is the result of an extensive refurbishment that ended in 2009. The galleries for the Islamic Middle East are near the rooms of the Mediterranean World, Medieval Cyprus, and Mughal India. A strong focus lies on ceramics: displays include a range of medieval to early modern ceramics, such as these examples (Figure 10). One particularly interesting case focuses on fake ceramics: some were made in the nineteenth century, such as this Iranian imitation of a sixteenth-century Ottoman Iznik plate (Figure 11), while the date of this thirteenth-century Kashan plate composed of several fragmentary pieces is of an unknown date (Figure 12).

Figure 10: Examples of Islamic ceramics shown at the Ashmolean Museum. The plate at the center was probably made in Fustat, Cairo, 10th to 12th c., EA1978.2161 (P. Blessing)

Figure 11: Fake Iznik plate, Iran, 1890s, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, EA 1978.1483 (P. Blessing)

Figure 12: Composite Kashan plate, original pieces dated 1206–07 CE (604 AH) with addition of other fragments (some removed after museum acquisition), Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, EA1978.2320 (P. Blessing)

And, last but not least, in the exhibit devoted to textiles, robes made in Saudi Arabia around 1916 and given to T.E. Lawrence—better known as Lawrence of Arabia—are shown (Figure 13).

Figure 13: Robe, shirt, headdress, sandals, ring and dagger, given to T.E. Lawrence in 1916, on loan from All Souls College, Oxford University, shown as Ashmolean Museum (P. Blessing)

Suggested Readings:

Demerdash, Nancy. “Review: ‘Arts de l’Islam’ at the Musée du Louvre,” International Journal of Islamic Architecture 2, no. 1 (January, 2013): 226–230.

Roxburgh, David. “'Open Sesame!' David J. Roxburgh on the Musee du Louvre's Galleries of Islamic Art,” Art Forum 51, no. 5 (2013): 61–64.

Roxburgh, David. “The New Galleries for ‘The Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia,’ Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,” Art Bulletin 94, no. 4 (December 2012): 643–646.

Over the last ten years, several collections of Islamic art in major collections around the globe received new displays; these include the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Louvre in Paris, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, and the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art in Istanbul that I will discuss in my next post. The Museum for Islamic Art in Berlin is scheduled to move to a new space within the larger renovation project of the Museum Island and particularly the Pergamon Museum, to be completed by 2025. Admittedly, I have not yet had a chance to visit the David Collection in Copenhagen, which has a strong focus on Islamic art. New museums, such as the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, opened in 2014, have sprung up as well. At the same time, collections containing large numbers of Islamic objects, such as that of the Musée des Tissus in Lyon, France, are at peril: the museum may close if new options for funding are not found. In this context, the dynamic world of museum collections is closely tied to politics, both at the level of spending cuts for culture, and in the connection to the antiques trade and preservation of cultural heritage from conflict regions.

Today, I will focus on collections in Italy, France, and the United Kingdom that I visited in the last few months. Of the collections mentioned above, I am also familiar with the Metropolitan Museum and the Berlin collection. The latter is left out here, because it will reinstalled at a later point; I would, however, like to point to the excellent special exhibition about former director and historian of Islamic art, Friedrich Sarre (1865–1945), on view until January 24, 2016. As I visited the exhibits and later discussed some of them with colleagues, I became more and more aware of the biases of an art historian inherent in my view on these displays. Thus, I find it hard to assess the view of the general public going into the galleries without prior knowledge of Islamic art, and can’t help looking out for the major pieces I know to be located in each collection.

This summer, in Rome, I visited for the first time the Museo Nazionale d’Arte Orientale, home to one of the largest collections of Islamic art in Italy. Within this collection, a main focus are objects from the excavations at Ghazni, Afghanistan, the capital of the Ghaznavid dynasty that ruled over present-day Afghanistan, north-eastern Iran, and northern India from the late tenth to the mid-twelfth centuries. Excavations at the sites were conducted by the now-defunct Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente (ISIAO) in the late 1950s and the 1960s (Figure 1). The excavations mostly investigated the palace of Ghaznavid sultan Masud III (r. 1099–1115); major finds include carved marble panels that served as wall decoration (Figure 2). Overall, the collection unfortunately remains on the margins of Rome’s museum circuit, with its masses of visitors streaming into sites such as the Vatican Museums, but bypassing other exhibits such as this. In addition to Islamic art, the collection also has a strong focus on East Asia, including China, Japan, and Korea; the building itself is worth a visit, too (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Panel describing the history of the Ghazni excavations, Museo Nazionale d’Arte Orientale, Rome (P. Blessing)

Figure 2: Detail of marble panel from the Ghazni excavations, Museo Nazionale d’Arte Orientale, Rome (P. Blessing)

Figure 3: Nineteenth-century chandelier, Museo Nazionale d’Arte Orientale, Rome (P. Blessing)

Walking through Rome, I came across numerous posters of another exhibition (Figure 4). Objects from the al-Sabah collection of Islamic art, based in the Dar al-Athar al-Islamiyya in Kuwait, happened to be in view in the Scuderie del Quirinale. This traveling exhibition was a chance to see objects that are not often easily accessible; even though photography was not permitted in the show, some of the objects and others from the collection can be viewed on the Google Art Project, although item information on the site, unfortunately, is very limited.

Figure 4: Poster for the exhibition of the al-Sabah collection in Rome (P. Blessing)

Figure 5: Roof over Islamic galleries, Louvre, Paris, seen from above (P. Blessing)

Figure 6: Upper floor of Islamic galleries, Louvre, Paris, with eleventh-century stucco inscription frieze from Saveh, Iran (P. Blessing)

Moving on to Paris, the Louvre opened its new permanent exhibition of Islamic art in fall 2012. A courtyard received a new roof (Figure 5), and two floors of exhibition space were built into it (Figure 6). The space is a first rather overwhelming, and one needs several visits to form a better view of the exhibit. On the upper floor, seen in figure 6, light flows through the roof structure while the lower floor is quite dark. The narrative is largely chronological, beginning with early Islam on the first floor. Thematic cases include the role of calligraphy in Islamic art and the influence of Chinese ceramics on the early Islamic production. Pieces from major sites such as the ninth-century Abbasid palaces of Samarra, and well-known objects such as the tenth-century ivory pyxis of Mughira from Umayyad Spain are shown alongside extensive exhibits from the site of Siraf on the Persian Gulf, including ceramics influenced by Chinese examples. The lower level is harder to navigate, as the trajectory is not quite clear from the start. In effect, it is largely chronological, with the continuation of the medieval exhibits in the room at the far end, and the early modern display—the collection ends at 1800—in the center. Coming down the stairs from the upper floor, however, the visitor is not clearly guided in one or the other direction. The cases with book paintings, placed quite understandably in a little-lit spot, are unfortunately easy to miss due to their location underneath the stairs. Other displays, however, are well presented, such as the selection of images of royal figures on ceramics. A fifteenth-century Mamluk stone porch, taken to Paris from Cairo for the 1889 World Fair and not on view for over a century, was restored and reassembled for the new display as an instructive video explains. Overall, several short videos about production processes—of, for instance, ceramics and inlaid metalwork—are worth the time for their simple and well-designed explanations of techniques. Additionally, replicas of several objects are available to touch. While these displays, featuring labels in Braille writing, are primarily intended for visitors with impaired vision, they are attractive for all. Although the pieces are all made of the same material and don’t provide a sense of texture, small samples of materials are added for that purpose.

The Institut du Monde Arabe, research center, library and museum all in one has a permanent exhibit focusing on Islamic art. The narrative here, rather than focusing on the historical trajectory of dynasties, revolves around themes such as medicine and astronomy, in addition to some chronological displays. Highlights are fragments of wall-paintings (Figure 7) from the seventh-century desert castle of Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi in Syria, and pieces of mosaic from the Great Mosque of Damascus, on loan from the National Museum in Damascus. While it is wonderful to see these objects in Paris, this does little to distract from the fact that both monuments and the large number of finds from Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi in Syria are out of reach. In a recent interview with Swiss newspaper Der Bund, Mohamed Fakhro, deputy director of the National Museum in Aleppo and now living in Germany where he pursues research, pointed out the extent to which the destruction of cultural heritage adds to the human suffering caused by the conflict.

Figure 7: Fragment of wall painting from Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi, Syria, on loan to the Institut to Monde Arabe, Paris (P. Blessing)

In the UK, several museums have new displays of Islamic art, while the British Museum recently announced that new Islamic galleries would open in 2018. The Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London opened its Jameel Gallery of Islamic Art in 2008 (Figure 8). The center of the room is dominated by the Ardabil carpet, a very large (10.51m x 5.34m) sixteenth-century piece that comes from the ancestral shrine of the Safavid dynasty in northern Iran. The other exhibits are arranged around the room, both along the walls (Figure 9) and in cases that separate the central space from the circuit around.

Figure 8: Jameel Gallery of Islamic Art, Victoria and Albert Museum, London (P. Blessing)

Figure 9: Tiles in carved terracotta technique from tomb of Buyanquli Khan, Bukhara, Uzbekistan, built in 1358; preserved at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (P. Blessing)

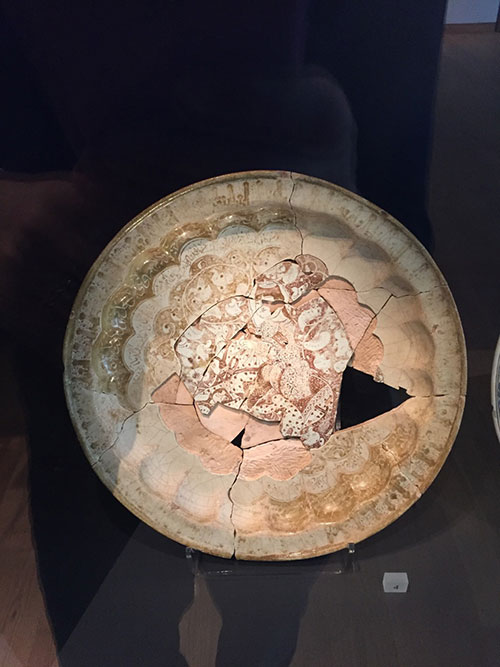

The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, in its current state, is the result of an extensive refurbishment that ended in 2009. The galleries for the Islamic Middle East are near the rooms of the Mediterranean World, Medieval Cyprus, and Mughal India. A strong focus lies on ceramics: displays include a range of medieval to early modern ceramics, such as these examples (Figure 10). One particularly interesting case focuses on fake ceramics: some were made in the nineteenth century, such as this Iranian imitation of a sixteenth-century Ottoman Iznik plate (Figure 11), while the date of this thirteenth-century Kashan plate composed of several fragmentary pieces is of an unknown date (Figure 12).

Figure 10: Examples of Islamic ceramics shown at the Ashmolean Museum. The plate at the center was probably made in Fustat, Cairo, 10th to 12th c., EA1978.2161 (P. Blessing)

Figure 11: Fake Iznik plate, Iran, 1890s, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, EA 1978.1483 (P. Blessing)

Figure 12: Composite Kashan plate, original pieces dated 1206–07 CE (604 AH) with addition of other fragments (some removed after museum acquisition), Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, EA1978.2320 (P. Blessing)

And, last but not least, in the exhibit devoted to textiles, robes made in Saudi Arabia around 1916 and given to T.E. Lawrence—better known as Lawrence of Arabia—are shown (Figure 13).

Figure 13: Robe, shirt, headdress, sandals, ring and dagger, given to T.E. Lawrence in 1916, on loan from All Souls College, Oxford University, shown as Ashmolean Museum (P. Blessing)

Suggested Readings:

Demerdash, Nancy. “Review: ‘Arts de l’Islam’ at the Musée du Louvre,” International Journal of Islamic Architecture 2, no. 1 (January, 2013): 226–230.

Roxburgh, David. “'Open Sesame!' David J. Roxburgh on the Musee du Louvre's Galleries of Islamic Art,” Art Forum 51, no. 5 (2013): 61–64.

Roxburgh, David. “The New Galleries for ‘The Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia,’ Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,” Art Bulletin 94, no. 4 (December 2012): 643–646.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top