-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Creating an Ottoman Capital: Istanbul in the Late Fifteenth Century

This blog post will continue last month’s account of Istanbul as a city between past and present, between historical monuments and skyscrapers. The focus this time will be on the second half of the fifteenth century, and on the shaping of the new Ottoman capital following the conquest of Constantinople and the end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453. The conquest was not sudden, and Ottoman sultan Mehmed II, known as the Conqueror, had long prepared it. Fortresses on both sides of the Bosphorus—Rumeli Hisar on the European and Anadolu Hisar on the Asian shore —were built in as part of the Ottoman approach on the Byzantine capital. Nowadays surrounded by restaurants and cut off from the shore by roads, the fortresses are no longer quite as forbidding, yet they still impress when seen from a distance (Figures 1 and 2).

Figures 1 and 2: Rumeli Hisar, Istanbul, view and close up (P. Blessing)

The Ottomans did not immediately set about fully transforming the city—some steps were taken as soon as the city was in hand, such as the conversion of its cathedral, Hagia Sophia, into a mosque (Figures 3 and 4). The overall changes to the urban fabric, however, including the construction of mosques and a new palace, took place over several decades to come.

Figures 3 and 4: Hagia Sophia, interior, photographs taken in January 2011 when all scaffoldings were down (P. Blessing)

Only ten years after the conquest, in 1463, was a new mosque built under the sultan’s name: the Fatih Mosque, or Mosque of the Conqueror, named after the victorious ruler. Largely destroyed in a devastating earthquake in 1766, the current building is mostly the result of reconstruction at that time, although the courtyard is still largely original (Figures 5 and 6). The site was well chosen: the Church of the Holy Apostles—the burial place of Byzantine emperors—was torn down and the patriarchate of the Greek Orthodox Church relocated. Seen from the Golden Horn, moreover, the mosque dominates the church of the Pantokrator Monastery, and imperial foundation soon converted into a mosque and still used as such today. Both the mosque and the cistern below (Figure 7) have been the subject of several restoration projects over the years, including most recently in 2014.

Figure 5: Fatih Mosque, view, with Pantokrator Church/ Zeyrek Mosque in front (P. Blessing)

Figure 6: Fatih Mosque, courtyard (P. Blessing)

Figure 7: Zeyrek Cistern, during restoration in August 2008 (P. Blessing)

The sultan himself became part of the myth of the conquest: Italian painter Gentile Bellini’s portrait of Mehmed II can be found on advertisements (Figure 8) and the legend of an Ottoman rider leaping over the city walls during the conquest has found its way onto a municipal emblem (Figure 9).

Figure 8: Advertisement on the façade of an appliance store, using Gentile Bellini’s portrait of Mehmed the Conqueror, photograph taken in the Fatih neighborhood in June 2014 (P. Blessing)

Figure 9: Emblem of the Faith municipality, opposite the Mahmud Pasha Mosque near the Grand Bazaar (P. Blessing)

Mehmed II was not the only patron of architecture: in a targeted, long-term project that Çiğdem Kafescioğlu has studied in detail, notables and particularly the sultan’s grand-viziers were responsible for the construction of mosque complexes. In several examples, only the mosques are well preserved and the subsidiary buildings have disappeared or are at various stages of decay, as Kafescioğlu outlines. The new mosque complexes were located in various places throughout the city, on both the European and Asian sides. Located near the Grand Bazaar, the Mosque of Mahmud Pasha was built in 1462–63. The building evokes the small early Ottoman mosques in its plan and exterior aspect (Figures 10 to 12). The patron’s mausoleum, however, located directly behind the mosque, has an exterior decoration of turquoise tile inlaid into a marble covering, forming geometric patterns (Figures 13 to 15). In her study of late fifteenth-century Istanbul, Kafescioğlu designated this decoration as Timurid without further elaborating, yet other references come to mind, including the stone-carved geometric patterns on the portals of thirteenth-century Seljuk monuments in central Anatolia. The building has been undergoing restoration for several years, covered in scaffolding and its surroundings becoming a maze of steel barriers (Figures 16 to 18), and I have not yet been able to visit the interior.

Figures 10 to 12: Mahmud Pasha Mosque, Istanbul, views (P. Blessing)

Figures 13 to 15: Mahmud Pasha Mausoleum, Istanbul, view and details (P. Blessing)

Figures 16 to 18: Mahmud Pasha Mosque, Istanbul, porch and surroundings (P. Blessing)

Located on the Asian side of the Bosphorus, in Üsküdar, the Rum Mehmed Pasha Mosque, built in 1471, takes on the silhouette of a Byzantine church (Figure 19). It towers on a hillside, visible from afar in the winter but hidden behind the leaves of nearby trees in the summer. Yet the exterior is deceptive, and only superficially points to the aesthetic of churches in converted into mosques. In the interior of the mosque, the dome is painted in scrolls and leaves that point east, and the dome rests on muqarnas pendentives (Figure 20).

Figure 19: View of shore at Üsküdar, Istanbul with Rum Mehmed Pasha Mosque, at center and Şemsî Ahmed Pasha Mosque at front left (P. Blessing)

Figure 20: Rum Mehmed Pasha Mosque, Istanbul, interior (P. Blessing)

Back on the European shore, near Topkapı Palace, only the mosque and hamam remain from the complex of İshak Pasha, founded in 1483 (Figures 21 and 22). While the mosque is still in use, the hamam is an empty shell; the terrace of a nearby hotel affords a rare glimpse of the interior (Figure 23). This state of preservation is typical in that often mosques continue to be used while other buildings fall into disrepair, are abandoned or used for purposes detrimental to the historical fabric.

Figure 21: İshak Pasha Mosque, view (P. Blessing)

Figure 22: İshak Pasha Hamam, view (P. Blessing)

Figure 23: İshak Pasha Hamam, interior (P. Blessing)

In addition to these problems in viewing fifteenth-century mosque complexes in their entirety, a further complication is the fact that roads often cut viewpoints, and make access difficult. An example of this is the Has Murad Pasha Mosque (1465–71) in the Aksaray neighborhood, enclosed by highways and tramway lines (Figure 24), so that even taking a good view of the monument becomes a challenge.

Figure 24: Has Murad Pasha Mosque, view (P. Blessing)

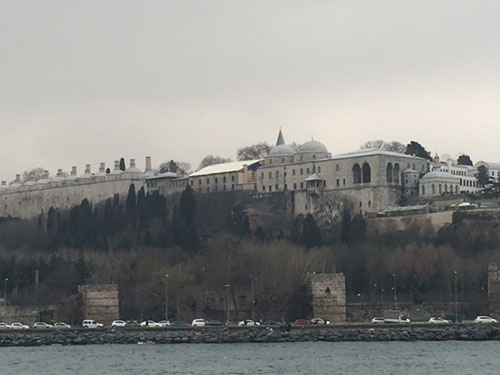

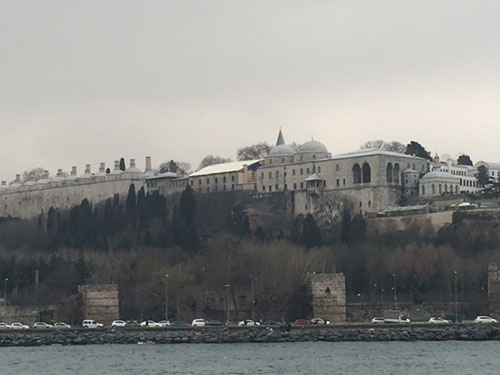

While these mosque complexes were important parts of the construction of Constantinople-Istanbul as the Ottoman capital, this overview would not be complete without a glimpse at Topkapı Palace, founded by Mehmed II and inhabited until the late nineteenth century (Figure 25). The building complex and its transformation over the centuries have been studied by Gülru Necipoğlu. Here, I would like to present the so-called Çinili Köşk (Tiled Pavilion), built in 1472 (Figure 26). Nowadays separated from the premises of the palace by the Archaeological Museum (Figure 27), it is an example of the fifteenth-century negotiation between varied influences in Ottoman architecture. The tile-work (Figures 28 and 29), made by tile-makers from Khurasan, points to Timurid architecture, yet in the overall effect is quite different from that of the supposed models in Central Asia, in part also because of the use of cut marble combined with the tiles. I will further explore this question in March, when discussing early Ottoman architecture elsewhere in Turkey.

Figure 25: Topkapı Palace, view from the Bosphorus (P. Blessing)

Figure 26: Çinili Köşk (Tiled Pavilion), view, June 2014 (P. Blessing)

Figure 27: Istanbul Archaeological Museum, view, June 2014 (P. Blessing)

Figures 28 and 29: Çinili Köşk (Tiled Pavilion), detail of exterior tile and marble decoration (P. Blessing)

Bibliography:

Çiğdem Kafescioğlu, Constantinopolis/ Istanbul: Cultural encounter, imperial vision, and the construction of the Ottoman capital, University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2009.

Gülru Necipoğlu, Architecture, Ceremonial, and Power – The Topkapi Palace in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991.

Gülru Necipoğlu, “From International Timurid to Ottoman: A Change of Taste in Sixteenth-Century Ceramic Tiles,” Muqarnas 7 (1990): 136-170.

Gülru Necipoğlu, “ ‘Virtual Archaeology’ in Light of a New Document on the Topkapı Palace’s Waterworks and Earliest Buildings, ca. 1509,” Muqarnas 30 (2013): 315-350.

Figures 1 and 2: Rumeli Hisar, Istanbul, view and close up (P. Blessing)

The Ottomans did not immediately set about fully transforming the city—some steps were taken as soon as the city was in hand, such as the conversion of its cathedral, Hagia Sophia, into a mosque (Figures 3 and 4). The overall changes to the urban fabric, however, including the construction of mosques and a new palace, took place over several decades to come.

Figures 3 and 4: Hagia Sophia, interior, photographs taken in January 2011 when all scaffoldings were down (P. Blessing)

Only ten years after the conquest, in 1463, was a new mosque built under the sultan’s name: the Fatih Mosque, or Mosque of the Conqueror, named after the victorious ruler. Largely destroyed in a devastating earthquake in 1766, the current building is mostly the result of reconstruction at that time, although the courtyard is still largely original (Figures 5 and 6). The site was well chosen: the Church of the Holy Apostles—the burial place of Byzantine emperors—was torn down and the patriarchate of the Greek Orthodox Church relocated. Seen from the Golden Horn, moreover, the mosque dominates the church of the Pantokrator Monastery, and imperial foundation soon converted into a mosque and still used as such today. Both the mosque and the cistern below (Figure 7) have been the subject of several restoration projects over the years, including most recently in 2014.

Figure 5: Fatih Mosque, view, with Pantokrator Church/ Zeyrek Mosque in front (P. Blessing)

Figure 6: Fatih Mosque, courtyard (P. Blessing)

Figure 7: Zeyrek Cistern, during restoration in August 2008 (P. Blessing)

The sultan himself became part of the myth of the conquest: Italian painter Gentile Bellini’s portrait of Mehmed II can be found on advertisements (Figure 8) and the legend of an Ottoman rider leaping over the city walls during the conquest has found its way onto a municipal emblem (Figure 9).

Figure 8: Advertisement on the façade of an appliance store, using Gentile Bellini’s portrait of Mehmed the Conqueror, photograph taken in the Fatih neighborhood in June 2014 (P. Blessing)

Figure 9: Emblem of the Faith municipality, opposite the Mahmud Pasha Mosque near the Grand Bazaar (P. Blessing)

Mehmed II was not the only patron of architecture: in a targeted, long-term project that Çiğdem Kafescioğlu has studied in detail, notables and particularly the sultan’s grand-viziers were responsible for the construction of mosque complexes. In several examples, only the mosques are well preserved and the subsidiary buildings have disappeared or are at various stages of decay, as Kafescioğlu outlines. The new mosque complexes were located in various places throughout the city, on both the European and Asian sides. Located near the Grand Bazaar, the Mosque of Mahmud Pasha was built in 1462–63. The building evokes the small early Ottoman mosques in its plan and exterior aspect (Figures 10 to 12). The patron’s mausoleum, however, located directly behind the mosque, has an exterior decoration of turquoise tile inlaid into a marble covering, forming geometric patterns (Figures 13 to 15). In her study of late fifteenth-century Istanbul, Kafescioğlu designated this decoration as Timurid without further elaborating, yet other references come to mind, including the stone-carved geometric patterns on the portals of thirteenth-century Seljuk monuments in central Anatolia. The building has been undergoing restoration for several years, covered in scaffolding and its surroundings becoming a maze of steel barriers (Figures 16 to 18), and I have not yet been able to visit the interior.

Figures 10 to 12: Mahmud Pasha Mosque, Istanbul, views (P. Blessing)

Figures 13 to 15: Mahmud Pasha Mausoleum, Istanbul, view and details (P. Blessing)

Figures 16 to 18: Mahmud Pasha Mosque, Istanbul, porch and surroundings (P. Blessing)

Located on the Asian side of the Bosphorus, in Üsküdar, the Rum Mehmed Pasha Mosque, built in 1471, takes on the silhouette of a Byzantine church (Figure 19). It towers on a hillside, visible from afar in the winter but hidden behind the leaves of nearby trees in the summer. Yet the exterior is deceptive, and only superficially points to the aesthetic of churches in converted into mosques. In the interior of the mosque, the dome is painted in scrolls and leaves that point east, and the dome rests on muqarnas pendentives (Figure 20).

Figure 19: View of shore at Üsküdar, Istanbul with Rum Mehmed Pasha Mosque, at center and Şemsî Ahmed Pasha Mosque at front left (P. Blessing)

Figure 20: Rum Mehmed Pasha Mosque, Istanbul, interior (P. Blessing)

Back on the European shore, near Topkapı Palace, only the mosque and hamam remain from the complex of İshak Pasha, founded in 1483 (Figures 21 and 22). While the mosque is still in use, the hamam is an empty shell; the terrace of a nearby hotel affords a rare glimpse of the interior (Figure 23). This state of preservation is typical in that often mosques continue to be used while other buildings fall into disrepair, are abandoned or used for purposes detrimental to the historical fabric.

Figure 21: İshak Pasha Mosque, view (P. Blessing)

Figure 22: İshak Pasha Hamam, view (P. Blessing)

Figure 23: İshak Pasha Hamam, interior (P. Blessing)

In addition to these problems in viewing fifteenth-century mosque complexes in their entirety, a further complication is the fact that roads often cut viewpoints, and make access difficult. An example of this is the Has Murad Pasha Mosque (1465–71) in the Aksaray neighborhood, enclosed by highways and tramway lines (Figure 24), so that even taking a good view of the monument becomes a challenge.

Figure 24: Has Murad Pasha Mosque, view (P. Blessing)

While these mosque complexes were important parts of the construction of Constantinople-Istanbul as the Ottoman capital, this overview would not be complete without a glimpse at Topkapı Palace, founded by Mehmed II and inhabited until the late nineteenth century (Figure 25). The building complex and its transformation over the centuries have been studied by Gülru Necipoğlu. Here, I would like to present the so-called Çinili Köşk (Tiled Pavilion), built in 1472 (Figure 26). Nowadays separated from the premises of the palace by the Archaeological Museum (Figure 27), it is an example of the fifteenth-century negotiation between varied influences in Ottoman architecture. The tile-work (Figures 28 and 29), made by tile-makers from Khurasan, points to Timurid architecture, yet in the overall effect is quite different from that of the supposed models in Central Asia, in part also because of the use of cut marble combined with the tiles. I will further explore this question in March, when discussing early Ottoman architecture elsewhere in Turkey.

Figure 25: Topkapı Palace, view from the Bosphorus (P. Blessing)

Figure 26: Çinili Köşk (Tiled Pavilion), view, June 2014 (P. Blessing)

Figure 27: Istanbul Archaeological Museum, view, June 2014 (P. Blessing)

Figures 28 and 29: Çinili Köşk (Tiled Pavilion), detail of exterior tile and marble decoration (P. Blessing)

Bibliography:

Çiğdem Kafescioğlu, Constantinopolis/ Istanbul: Cultural encounter, imperial vision, and the construction of the Ottoman capital, University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2009.

Gülru Necipoğlu, Architecture, Ceremonial, and Power – The Topkapi Palace in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991.

Gülru Necipoğlu, “From International Timurid to Ottoman: A Change of Taste in Sixteenth-Century Ceramic Tiles,” Muqarnas 7 (1990): 136-170.

Gülru Necipoğlu, “ ‘Virtual Archaeology’ in Light of a New Document on the Topkapı Palace’s Waterworks and Earliest Buildings, ca. 1509,” Muqarnas 30 (2013): 315-350.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top