-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Fjords and Repurposed Sites: Explorations around Iceland’s Ring Road

All photographs and videos are by the author, unless otherwise noted.

Last month, I noted that the September blog post would cover the Faroe Islands, but after an assessment of the material I gathered from my trip around the Ring Road of Iceland, it seemed more logical to draw my travels in Iceland to a close with this month’s post. October’s post will focus entirely on the Faroe Islands: the architecture, the infrastructure, and a number of tourist-centric sites on this largely untouched archipelago.

Although the rapidly shortening days in Iceland were a constant reminder of summer’s end and the approach of the dark winter hours, the colored display of the changing in seasons in the landscape was unexpected. With few trees, Iceland is certainly not a place for 'leaf peepers', but I was quite surprised to witness the changes in the lunar landscape: the bright purple, but invasive flowers (lupine) that liberally sprouted among the lava rocks in the summer disappeared and both the moss and brush started to change colors, the latter transitioning from vibrant green to rich shades of ochre and red (Figure 1 and 2).

Figure 1. A small parish church in the Westfjords.

Figure 2. An aerial view of a portion of Lake Myvatn illustrating the changing fall foliage.

The birches of the northern part of the nation were changing color too, giving the landscapes of Akureyri a distinctly autumn palette to compliment the bright colors of the metal-clad stores and warehouses. Along with the changing colors, it was clear that the summer season was over for many places on the island: sheep herders roamed the northern part of the country driving the animals back to local farms (Figure 3), many hotels outside of larger cities had closed for the year, the rural churches that were typically open for casual tourism were now locked, and the vast majority of museums had adopted shortened hours or closed entirely in preparation for winter. Nonetheless, certain destinations such as the Golden Circle, Lake Myvatn, and prime towns along the Ring Road, like Vík along the south coast, were still welcoming a steady stream of visitors in tour buses and camper vans.

Figure 3. A large-scale sheep drive along the northern coast.

Although Vík is not a particularly large town, with a population of less than 300, the location makes it a convenient base for those wishing to explore black sand beaches, the glacial lake, and natural rock formations. To highlight the rapidly changing and expanding tourist season, the Icelandair hotel in Vík serves as an ideal case study. Opened just three years ago, the thirty-six-room hotel was a seasonal endeavor, catering to the summer tourists. In its first year, there were only a handful of rooms occupied from September to May but last year, the ‘high season’ expanded so that only November through February were the quieter months. This year, the hotel manager explained with equal measures of enthusiasm and trepidation, it is projected that the hotel will be fully booked through all seasons. Around the capital region and the southern coast, it is clear that developers are scrambling to meet the demand for lodging. By Vík, there are several new hotels under construction: one a large and looming black mass with jarring angles that does little to fit into the surrounding landscape and the other a prefab experiment of guest room pods.

My extended trip around the island followed the Ring Road in a clockwise manner, with many excursions along minor, one-way roads. I stopped at major sites and national parks but was also interested in visiting some of the historic sites that, oddly, attract little attention, as well as several of the nation’s smaller towns that are leveraging local resources in hopes of attracting visitors. A number of sites are identified on this Google Map and this will, hopefully, be a useful resource for anyone wishing to visit the island and explore sites beyond prescriptive tourism routes. This post will not be a road trip journal, exploring sites geographically or chronologically. Instead, it will examine three building types that I continually encountered on my travels: religious sites, adaptive reuse projects transforming abandoned structures into new museums, and new visitor centers.

Churches

Based on my explorations around Iceland, there are three predominant forms for churches. Firstly, there are turf-covered wooden churches that are representative of the earliest Christian sites of worship. Next, there are simple and utilitarian churches with narrow naves, coffered ceilings, and flanking side aisles. These small, parish churches are colorful and symmetrical, both inside and out. The outstanding churches on the island are mid-to-late 20th century examples of geometrically experimental brutalism.

With over 350 churches on the island, vernacular and modernist examples can be found throughout the countryside, next to lava fields, and along steep coastal cliffs. Even the smallest of towns seems to have a compelling example of religious architecture that, generally, is well preserved and surrounded by a carefully manicured landscape. Based on Icelandic census reports, the plethora of parish churches on the island should be no surprise: according to recent records, about 80% of the nation’s population are members of the Lutheran State Church and another 10% are members of other Christian denominations. However, these numbers are deceiving since the National Registry records parish membership for new babies; on paper, Iceland has one of the highest percentages of registered religious devotees but few are active practitioners. Although many buildings still welcome local congregations, it seems that the majority of these churches now serve, primarily, as scenic sites: the six preserved turf churches have been adopted by the National Museum of Iceland and the corrugated metal cladding of the rustic parish churches glimmer in the sun and rain, adding another picturesque element to the already striking scenery of Iceland’s natural landscape (Figures 4 and 5).

Figures 4 and 5. The church at Glaumbær (1926) mixes late 19th century timber building traditions with the practical architectural approaches of the early 20th century that championed the use of corrugated metal as weatherproofing, even on sacred buildings.

The oldest turf church in the nation, Grafarkirkja, is a small chapel northwest of Akureyri in Gröf, Skagafjörðu that appears on few maps or tourist itineraries (Figures 6 and 7). Built by Gísli Þorláksson, the bishop of Hólar in the late 17th century, the church underwent a major reconstruction in 1950 under the stewardship of the National Museum of Iceland. Encircled by a burial ground and an expansive, open landscape, the low, turf-covered church blends into its surroundings. Upon closer inspection, however, the church has intricately carved details on the exterior, such as a delicate wooden weathervane, and complex joinery within the stave interior.

Figures 6 and 7. Grafarkirkja was reconstructed in the 1950s and underwent a conservation project in 2011; however, these interventions carefully protected the integrity and surrounding landscape of the site by using traditional hand tools to craft the pieces needed to replace weathered boards. The tar coating helps weatherproof the building and on the treated wooden surface one can see that swarms of midges (Icelandic black flies) were attracted to and eventually encased within the building’s protective coating.

Located just south of Grafarkirkja near the intersection of the Ring Road and route 752 is Víðimýrarkirkja (1834), another, larger turf church with apertures puncturing the sod roof (Figures 8-10). Saurbæjarkirkja (1858) in Eyjafjordur has similar details to Víðimýrarkirkja however the elements supporting the bell of Saurbæjarkirkja, used to announce services, are still in place (Figures 11 and 12).

Figures 8-10. Víðimýrarkirkja in Skagafjörður is one of the protected buildings under the care of the National Museum of Iceland and has several intricate details, despite its small size. The building is surrounded by a laid stonewall capped with turf and the earthen retaining walls of the church have a chevron pattern within the layers of turf.

Figures 11 and 12. Like Víðimýrarkirkja, Saurbæjarkirkja has a screen separating the choir from the nave.

As evidenced by the preserved stave farm (Figure 13) and recreated log house of Auðunarstofa (Figure 14) at Hólar, religious structures were not the only turf-covered buildings in Iceland. From the 12th century to the Reformation, Hólar was a religious and educational center in Iceland. With several historical structures and the Hólar University College (founded 1882), the small town still functions as an educational center for tourists and locals. For example, a replica of the Bishop of Hólar’s residence from the 14th century, the Auðunarstofa, demonstrates traditional building techniques and intricate detailing, ranging from the wooden door surrounds to the arabesque, metal hardware. Beyond the turf-covered buildings, visitors to Hólar can see the oldest stone church on the island: a tall and gabled red sandstone cathedral that looks entirely foreign within Iceland’s pre-1900s landscape of religious structures due to its scale and lack of an integrated spire (Video 1).

Figure 13. Nýibær (c.1860s) is a turf farm at Hólar with walls ranging from two to four feet thick.

Figure 14. The original Auðunarstofa, dating to the early 1300s, was torn down in 1810. The present reconstruction was completed in 2002 using traditional building techniques.

Video 1. Drone footage of the medieval town of Hólar in north Iceland.

Other examples of turf structures on the island are the larger turf farms of the 18th century that integrated agrarian production with sacred sites. One of the best-preserved examples of this typology can be found at the Glaumbaer (1750-1879) folk museum of Skagafjordur (Figure 15). Founded as a local museum in 1948, the farmhouse now falls under the stewardship of the National Museum of Iceland. The site contains a series of interconnected, turf-covered structures with decorative gable ends that face working yards (Figure 16). With a showcase of archaeological discoveries dating to the 11th century, the farmhouse is one of the best-preserved vicarages in the nation (Figures 17-19).1 The farmhouse contains pantries, furniture made from driftwood and deconstructed packing cases, and the remnants of the bi-yearly trips to the nearest fishing village. The baðstofa occupies one of the long sections of the interconnected turf farmhouse and was once the core, heated living space where inhabitants bathed, slept, and spent recreational hours (Figures 20-21). Here, visitors can envision life in the 18th century by inspecting the tightly packed, compartmental beds that are individually distinguished by carved bed panels featuring the name of the inhabitant, the year of construction, and, occasionally, an inscribed prayer. Several Icelandic writers and museum exhibits reveal that although the turf-covered buildings of Iceland are, now, highly romanticized, these structures were often damp, dark, and crowded.2 Ducking beneath the low ceilings and walking along the compressed corridors, it is hard to fathom how several families lived communally in the baðstofa and in close proximity to the spaces dedicated to livestock.

Figure 15. At one time an unstaffed site, visitor numbers to the folk museum have increased dramatically and elevated concerns about the site’s sustained conservation.

Figure 16. Like some of the other preserved turf churches of Iceland, the earthen layers of Glaumbær’s walls form decorative patterns that created a modular construction system and would be more resistant to water infiltration while adding to the aesthetic appeal of the structure.

Figures 17-19. Skylights and apertures in the gable ends illuminate the interior of the turf farm.

Figures 20 and 21. Children and extended family members used the unadorned portion of the baðstofa while the painted room along the gabled end was reserved for the vicar and his wife.

In addition to the turf farmhouse, Glaumbaer is home to two other brightly colored, wooden farmhouses that are representative of typical agrarian buildings from the 19th century as well as a corrugated iron and timber church from 1926. The site has a number of costumed interpreters, a café, two gift shops, and a large parking lot to accommodate visitors. Signs prohibiting dogs, smoking, and climbing on or between the structures reveal that despite the unique composition of the site, select visitors have not acted in the best interests of preservation.

With only a handful of turf-covered churches, the plethora of religious structures from late 19th and early 20th centuries are simple gabled constructions with a spire above the entry (Figure 22). These buildings typically accommodate less than fifty people and are made of either wood, clad in corrugated metal, or roughcast concrete. Most of these churches have white or cream walls that are accented with brightly colored aperture trim and matching metal roofs.

Figure 22. With several large apertures and a two-tiered tower with a hexagonal spire, the church at Akranes is one of the more decorative parish churches of the island.

The Bláakirkja [Blue Church] of Seyðisfjörður, however, stands out: unlike other sites around Iceland where a pale blue building would blend into the horizon, the harbor town’s placement within a deep valley of the Eastfjords means that the structure stands out against the mountainous background, shaped by the Fjarðará river and Gufufoss (Figure 23a and b). Seyðisfjörður was founded in 1848 as a trading post to the east and at the turn of the 20th century, it was the second largest city in Iceland. Illustrating its connections to Scandinavian neighbors, the town’s earliest structures, including portions of the church, were prefabricated in Norway. Today, the town has less than 700 inhabitants but it welcomes a stream of visitors every week as the port for the Smyril Line ferry MS Norröna that sails between Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Denmark (Figure 24).

Figure 23a. A collage of photographs from 1922 and 2016, showing how the entry to the Bláakirkja is now framed by a series of small, metal-clad cafes and guesthouses.

Figure 23b. The blue of the church of Seyðisfjörður against the mountains.

Figure 24. The approach to Seyðisfjörður as seen from the ferry from the Faroe Islands.

With few trees in the nation and a harsh climate for deciduous hardwoods, Iceland’s wooden building materials are typically imported. Driftwood, usually from Siberia, occasionally washes ashore but the waterlogged pieces are far too fragile to be used structurally (Figure 25).3

Figure 25. A view of one of the many fields of driftwood along the coast of the Westfjords.

Therefore, several of Iceland’s wooden churches are actually early examples of prefabrication: the church’s elements were designed and crafted in other Scandinavian countries then shipped to Iceland for assembly. For example, components of the Húsavíkurkirkja were made in Norway then shipped to the whaling town for construction in 1907: the scale, use of color, elaborate interior joists, and exterior decoration are like no other church on the island (Video 2 and Figures 26 and 27). As a wooden church with a riveted metal onion dome, the Grundkirkja (1905) in Eyjafjörður is another anomaly in Icelandic religious architecture (Figures 28-31).

Video 2. Drone footage of the harbor and unique church of Húsavík.

Figures 26 and 27. The tall structure, use of color, and articulated joinery immediately identify the Húsavíkirkja as an atypical building within Iceland’s sacred architecture.

Figures 28-31. Despite its unusual form and atypical patronage (a single farmer), the Grundarkirkja is rarely cited on Icelandic tourist maps or in tour books.

Due to their expense, churches were typically humble structures and in a nation with such a varied and tough landscape, the placement of churches seems to indicate that parishioners would rather sponsor a small place of worship within their immediate vicinity rather than collaborating with a neighboring town to fund a larger structure (Figures 32 and 33).

Figures 32 and 33. Perched near the coast, the small church of Búðir (1847-1851) is one of the oldest timber buildings in the nation.

By the early 1900s, it was common for churches to be clad in corrugated metal: it ensured better weatherproofing but the repeated meter of the material also mimicked the look of wooden board and batten siding that could be found on 19th century buildings (Figure 34).

Figure 34. This small parish church in a remote area of Arneshreppur sits along the Strandir coast of the Westfjords.

Around the 1930s, the wooden substructure used in churches was replaced with concrete (Figure 35). This made buildings cheaper and easier to construct given the limitations on lumber; however the material change was mandated in larger cities like Reykjavík and Akureyri. Here, the construction of new, wooden public buildings was largely banned in hopes of quelling urban fires.4 These regulations, alongside the economy of concrete construction and the desire to cultivate a new national aesthetic following’s Iceland’s independence, may explain why there are a number of sites of worship, scattered around the island, that are unexpected concrete masterpieces.

Figure 35. The once-red roof of the Ólafsfjarðarkirkja (c.1915) was replaced with grey during a recent conservation project and yellow accents were added to emphasize the concrete sills.

Although the capital’s skyline is dominated by one of the tallest and most recognizable architectural icons of the nation, Hallgrímskirkja (Figure 36), Reykjavík’s suburbs are also filled with fascinating modern churches (Figures 37-46).

Figure 36. Easily the most recognizable churches in Iceland, Hallgrímskirkja is just one of the island’s modernist icons.

Figure 37. As one of the first experimental constructions in concrete, the independent church of Kirkja Óháða Safnaðarins (1959), designed by Gunnar Hansson, features an array of clerestory windows and a vibrant, blue façade.

Figure 38-40. Located in the Hamraborg, Kópavogur suburb just south or the capital, the Kópavogskirkja (1957-1962) was designed by Hörður Bjarnason and the centralized plan capped with parabolic arches is cardinally orientated.

Figure 41. The Vídalínskirkju (1966) has undergone several additions but the intersecting gables of the original structure are still the dominant forms of the building.

.jpg?sfvrsn=b6dd5c9b_2)

Figure 42. Located above the Laugardalur Valley with a concrete spire that seems to rise from the rock, the Áskirkja (1983) was designed by Hjálmarsson and Haraldsson Architects.

Figures 43 and 44. Designed by Ferdinand Alfreðsson and Guðmundar Kr. Kristinsson, and Hörður Björnsson, the twelve-pointed star plan of the Breiðholtskirkja (1977-1988) transitions into a dramatic, open pinnacle.

Figure 45 and 46. Located west of the capital, near the Grótta Lighthouse of Seltjarnarnes, Seltjarnarneskirkja (1979-1989) was designed by Harðar Björnssonar.

Iceland’s prolific state architect Guðjón Samúelsson, can, in part, be credited for the initial wave of modernism in the capital as well as the northern industrial city of Akureyri (Video 3). His urban plan for the city in 1927 helped craft a new commercial and residential core that was more conductive to an industrialized and electrified city while the construction of the stacked towers of the Akureyrarkirkja (1940) responded to the forms of the nearby mountains of Eyjafjöður (Figures 47 and 48). Here, elements of the international style seamlessly blended with Icelandic regionalism. The examples provided demonstrate that modern churches were popular in metropolitan areas but other, iconic structures (at a range of scales) can be found throughout the nation (Figures 49-63).

Video 3. Drone footage of Akureyri, featuring the old urban center along the harbor and Samúelsson church at the top of the commercial summit.

Figures 47 and 48. Samúelsson emphasized the summit site of the Akureyrarkirkja (1938-1940) by placing a series 100 steps on axis with the nave.

Figure 49. En route from the capital to Þingvellir National Park, the small church of Mosfellskirkja (1965-1979) by Ragnar Emilsson is hard to miss. The sharp angles of the spire and folded gables of the parish church mimic the forms of the surrounding ridges.

Figure 50 and 51. Near the airport in Keflavík on the Reykjanes Peninsula is Ytri-Njarðvíkurkirkja (1979) by Ormar Þór Guðmundsson and Örnólfur Hall

Figure 52-55. North of the capital region, on the Snaefellsnas Peninsula, the soaring and skeletal church of Stykkishólmskirkja (1972-1990) designed by Finnish architect Jón Haraldsson dominates the skyline of Stykkishólmur.

Figures 56 and 57. The Egilsstaðakirkja (1974) of Egilsstaðir, Eastfjords serves as a visible landmark for the small town from the Ring Road.

Figure 58. Set within a town known for its geothermal greenhouses and natural hot pots, Hveragerði is home to a concrete church (1967-1972) with a steep gable and detached bell tower.

Figure 59. This small concrete and metal chapel in the remote area of Arneshreppur along the Strandir coast of the Westfjords sits near the early 20th century single nave church seen in figure 34.

Figures 60-63. Designed by Maggi Jónsson (b.1937), an Icelandic architect in practice since 1972 with several commissions for the University of Iceland, the board-formed concrete Brutalist church of Blönduós (1982-1993) takes inspiration from the form of a volcano and features skylight domes to illuminate subterranean meeting rooms.

Repurposed, Reclaimed, and Reconstructed5

Located along the smaller roads of Iceland’s fjords, several towns have actively cultivated grassroots tourism campaigns, hinged on their local resources and history. Many of these small towns are time capsules that capture Icelandic life in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Since they have less than 3,000 inhabitants, tourism is an attractive economic generator.

Hoping to curate important historical sites related to fishing and whaling, several entrepreneurial individuals and small towns have spent the last few decades converting abandoned and underused sites into museums and living history destinations. The most groundbreaking of these sites is the Herring Era Museum located in Siglufjörður. As one of the most prominent, and wealthy, harbors during the 'Herring Years' of 1903-1986, Siglufjörður was once known as the "Atlantic Klondike"(Figure 64). During peak operations, the town processed 20% of the nation's herring, an export that accounted for 40% of the nation's overall export revenue. The first factory of Siglufjörður was constructed in 1911 and over the next half a century, production grew: between 1950 and 1965, there were 120 companies producing salted herring and nine other companies dedicated to byproducts, such as meal for pet food and oil for various uses, including soap. The piers of Siglufjörður stretched 7.3km into the fjord but when the herring population collapsed in 1969 due to overfishing, Siglufjörður fell into a deep recession like many other towns of the north and east: Akureyri, Bolungarvík, Dagverðareyri, Dalvík, Djúpavík, Eskifjörður, Hjalteyri, Húsavík, Ingólfsfjörður, Krossanes, Þórshöfn, Neskaupstaður, Raufarhöfn, Reyðarfjörður, Seyðisfjörður, Skagaströnd, and Vopnafjörður

Figure 64. A fishing vessel, overflowing with herring, was a common sight in the 1950s. Photograph from the Reykjavík Museum of Photography, item GRÓ-004-061-2-2.

When the Old Norwegian Sailors’ Home of Siglufjörður, the Róaldsbrakki (1907), was threatened with demolition in 1984, a group of volunteers rallied to restore the building with the support of the Cultural Heritage Agency of Iceland (Figure 65). In the summer of 1994, the structure opened to the public as a site for collecting and interpreting the history of the region. Bolstered by a grant from the Ministry of Education in 1997, the volunteer group expanded their efforts and began to develop a master plan for the restoration of a portion of the harbor.

Figure 65. The restored Róaldsbrakki now houses a shop and storage on the ground floor and exhibitions on the upper floor. The area in front of the building also serves as a stage for a summer concert series.

In 1998, the group began the reconstruction of the Grána fishmeal and oils factory (c.1930s) by collecting preserved industrial artifacts from the abandoned factories of Ingólfsfjörður (1942-1952) and Hjalteyri (1937-1966) (Figure 66). Completed in 2003, the project received Iceland's first Innovation Tourist Board Award. The reconstruction of a typical herring port from 1938-1954 commenced the following year as did the construction of the boathouse, a large shed building to house a recreated fisherman’s store and eleven restored wooden boats from 1938 to 1954 (Figures 67 and 68). Along the harbor, the group restored a partially preserved slipway in hopes of providing a platform for interpreting shipbuilding practices from the 1930s to 1960s.

Figure 66. The old fishmeal factory has been restored with salvaged equipment from the abandoned factories of two herring ghost towns.

Figures 67 and 68. The new boathouse offers visitors a large and comfortable space to escape poor weather and explore traditional wooden boat construction, in detail.

After years of grassroots preservation and restoration, the non-profit renamed the site The Herring Era Museum in 2006 and transitioned the volunteer-managed property into a successful, full-time and professional museum endeavor. In its first years the museum had fewer than 2,000 visitors but today it welcomes over 25,000 a year, largely thanks to tour groups and improved access to the site because of the construction of the Héðinsfjörður tunnel in 2011. Since 2013, a professional boat builder has been employed to restore the adjacent slipways and piers, and in the summer months he works in the restored shipyard as part of living history initiatives at the site. Due to the popularity of the museum, there are plans to convert a late 19th century salt house into additional storage facilities for the museum’s ever-growing collection of industrial objects and other businesses in the town have profited from the museum’s success: once a struggling harbor, Siglufjörður now has several new hotels, restaurants, and shops (Figure 69).

Figure 69. The Herring Era Museum now dominates the harbor and it is easy to imagine how the museum may expand its efforts along the old fishing piers in future years.

Also related to the collapse of the herring industry and located in Árneshreppur of the Westfjords, is the abandoned industrial village of Djúpavík (Video 4). In addition to acting as a dramatic backdrop for the town, the adjacent waterfall provided hydroelectric power to fuel the once vibrant herring factory. Although still very much an industrial ruin and ghost town, Djúpavík is slowly resurrecting itself as a destination site for adventurous tourists and Iceland’s creative startups.

Video 4. Drone footage of the abandoned herring plant in Djúpavík of Iceland’s Westfjords.

Elías Stefánsson established the first herring salting station in Djúpavík in 1917, but the endeavor bankrupted in 1919. With a renewed drive to bring cutting-edge industry to an area that was, at the time, accessible only by ship, an innovative fishmeal and oil factory was constructed in 1935. With three stories spanning 90 meters, the factory was the largest concrete building in Iceland and the operation pioneered the use of heated storage tanks for oil, contained within three massive concrete cylinders (Figures 70-73). With a rapidly depleting herring stock, the factory closed in 1954. Exploring the site today, it is as if the workers simply walked away: the site is still scattered with tools, abandoned replacement cleats and bits for fishing boats, and rusting ship hulls (Figure 74).

Figures 70 and 71. These photographs from 1934 and 1935 reveal a bustling site with large-scale concrete construction projects and a substantial labor force. Photographs from the Reykjavik Museum of Photography, item numbers ARN-26 and 50.

Figure 72. The oil tanks are now empty but the heating coils are still visible on the floor of these massive industrial ruins.

Figure 73. This photograph shows the intact steel ship that is now a rusted skeleton, docked at the abandoned factory. Photograph from the Reykjavik Museum of Photography, item AGH-SJÓ-060.

Drawn to the area after a visit, a family purchased the factory in 1985 and they have been responsible for transitioning the abandoned town into a rustic site for summering Icelanders and entrepreneurial craftsmen and artists. They also purchased the factory’s kvennabraggann, a building used to house unmarried female factory workers, and converted the structure into Hotel Djúpavík.

Over the years, portions of the factory's old boathouses have repurposed as bays for craftsmen who welcome curious visitors into their workshops. Here, one can see everything from the restoration of classic cars to the production of fine furniture. Some unaltered parts of the factory are open to touring, providing visitors with the rare opportunity to explore interwar factory technology, while other portions, with their rough board-formed concrete walls and cracked windows, are now used as spaces for temporary art installations (Figures 75 and 76).

Figures 75 and 76. Although an eerie setting, the long corridors of the abandoned factory provide the ideal armature for displaying artwork and experimental installations.

Whereas The Herring Era Museum and Djúpavík are adaptive reuse projects that reveal a facet of the rise and fall of Iceland’s fishing industry, the Whaling Museum of Húsavík, located in Skjalfandaflói Bay, is a more recent tourism endeavor that attempts to explore the history whaling around the island. Founded in 1997, the collections soon outgrew rented space in town so the volunteers moved into an abandoned sheep slaughterhouse along the harbor (Figure 77). The shell of this utilitarian building is largely preserved, with only a few alterations such as the insertion of a suspended wooden walkway that allows visitors to get close views of the nearly one dozen whale skeletons on display (Figure 78).

Figure 77. The bright colors and cheerful decorations of the Whaling Museum mask the building’s unpleasant history.

Figure 78. The dimly lit upper story of the open plan museum houses a collection of whale skeletons.

The museum provides insight to the whaling history of the nation and the still-evolving shift from hunting whales to actively conserving their habitat, partially driven by the popularity of whale watching expeditions around the island. This was a theme I explored, briefly, in my inaugural blog post. In the museum, exhibits underscore that although whales and beastly sea creatures appeared in early maps (1585, 1640), as well as the Landnámabók [The Book of Settlement] and seventeen sagas, Vikings were not vigorous whalers. A beached whale, however, was known as a hvalreki , and the word’s contemporary translation is ‘a lucky find’: the discovery of a beached whale could sustain a community in the harsh climate and, consequently, the finder of hvalreki was compelled to report the discovery to his or her neighbors. There are records from the 16th century of Icelanders participating in pod drives into fjords, trapping whales and dolphins in a manner very similar to the communal hunts that still occur in the Faroe Islands but the first commercial whaling enterprises did not occur until the 17th and 18th centuries, fueled by the domestic need for whale oil. Between 1883 and 1989, there were fourteen whaling stations in Iceland, predominantly located in the Westfjords, with five stations in the Eastfjords and one north of the capital region. Whaling in the Eastfjords, however, lasted only a decade due to diminished species numbers. Under legislation from the International Whaling Commission, commercial whaling was suspended from 1986 through 2006, although Iceland was still permitted to hunt sixty large whales each year for scientific purposes. August 2007 marked the official termination of commercial whaling in the nation but whales are still hunted for domestic consumption, fueling the powerful phrase on the t-shirts of a volunteer agency, "whales are killed to feed tourists."

Once a harbor occupied with whale slaughters, Húsavík is now empowered by the conservation movement: it is known as the ‘whale-watching capital of Iceland’ and is also home to the University of Iceland’s Research Centre for studying the economic effect of tourism on the region. As the port of call for an array of whale watching ships and new ecotourism companies, Húsavík has reinvented itself as a carbon-neutral, tourist-centric enterprise (Figures 79 and 80).

Figures 79 and 80. The various touring vessels and street signs of Húsavík advertise the region’s profitable preoccupation with whales.

Breaking Ground: new buildings, new ideas

In the first few blog posts chronicling my studies in Iceland, I noted the extensive construction project underway in the capital region. These new builds are, predominantly, related to high-rise housing and mixed used commercial developments; however, there are a number of innovative projects underway across the nation that are directly tied to the massive influx of tourists in the last few years. As mentioned in the previous section, small towns are attracting visitors through the conversion of abandoned and underused sites into attractions, tourist centers, and museums; a number of new design projects around the country further illustrate regional investment in tourist culture. For example, despite the translated English name that invokes images of a cringe-worthy theme park, Viking World [Vikingaheimar] is a compelling site that aligns living history reconstructions with rich narratives and artifact interpretation (Figure 81). Located in Reykjanesbær by the Keflavík airport, the project was designed by prolific Icelandic architect Guðmundur Jónsson in 2009 as an architectural vessel to hold the Íslendingur, a reconstructed Gokstad Viking ship that sailed from Reykjavík to New York in 2000 to mark the millennial anniversary of Leif Erikson’s voyage (Figure 82). Outside, the site consists of a living history turf farmhouse and classroom; inside, exhibits about Viking settlements, burial rites, and archaeological excavations line the walls and the Viking ship reconstruction floats above visitors’ heads. From the upper gallery, visitors can board the ship and try to imagine how the early sailors made it, safely, across the Atlantic. Suspended between the glazed walls, providing unimpeded views of both the marsh and adjacent ocean, the building feels a bit like a full-scale iteration of a ship-in-a-bottle model and seems like a likely precedent for elements of the much grander Grimshaw’s Cutty Sark conservation project (2012).

Figure 81. The building’s unusual form is visible from both the Ring Road and harbor: the small structure’s curving wooden rain screen shields two, perpendicular glazed walls that are brightly illuminated in the evening hours.

Figure 82. From 2002 to 2006, the ship was housed along the Reykjanes Peninsula. In following years, an Icelandic consortium raised funds to conserve the vessel within an appropriate, conditioned dry-dock.

The Thorbergur Centre of Culture in Hali, Höfn, dedicated to writer Þórbergur Þórðarson (1888–1974), has a similar scale to Viking World but, unlike the transparent architecture of Viking World that entices visitors inside, the opaque exterior of the Thorbergur Centre acts as contemporary architecture parlante, featuring an oversized bookshelf of the author’s works (Figure 83).

Figure 83. The bold exterior masks a quiet and sophisticated exhibit at the cultural center.

Contained within a dimly lit metal shed, architects Sveinn Ívarsson and Jón Þórisson crafted a museum with a series of intertwined vignettes that literally put visitors into the world of Þórðarson (Figures 84 and 85). As a native of Hali who grew up in the Breiðabólsstaiður settlement of the Suðursveit, an isolated part of the island that saw few visitors besides French schooners in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Þórðarson frequently wrote of Iceland’s earliest settlers and farm life. Within the museum, opened in 2006, visitors can walked through a recreated section of his family’s turf-covered homestead while reading passages by the writer on illuminated boards. With these boards providing the majority of lighting within the exhibition space, visitors are, experientially, transported. The farmhouse demonstrates life before electricity and by walking over gravel ‘paths’ in the museum and climbing wooden steps, Þórðarson’s words come to life in the deconstructed farm house: “The cows were kept under the baðstofa loft. You could see their hind ends as you walked down the passage. They were part of the family, but were just built a bit differently from humans”.6

Figures 84 and 85. Although a small museum, the Thorbergur Centre weaves traditional 18th century agrarian architecture with elements of Iceland’s emerging urbanity in the early 20th century.

In 1909, Þórðarson moved to the capital and visitors walk through this transition from the farm to urban living within the exhibit, ultimately ending their trip through the comprehensive, albeit spatially compressed, architectural biography of the writer’s life in a reconstruction of the electrified living room of his funkis home at Hringbraut 45 that he called his ‘folk tales room’ and, later, ‘the room of changlings’. Through the exhibition, the museum evocatively puts the spaciousness, furnishings, and sounds of ambient radio from Þórðarson Reykjavík home in contrast with his birthplace in a baðstofa, shared with seven other family members and the livestock.

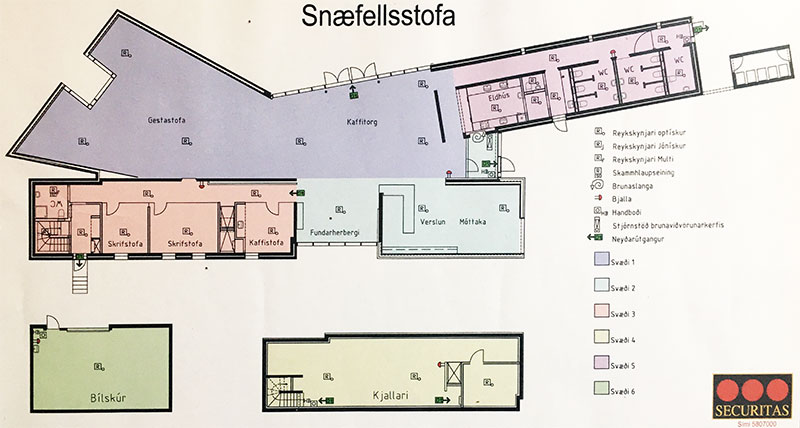

As small structures, Viking World and the Thorbergur Centre’s demonstrate strong partnerships between architects, landscape architects, and exhibit designers. Taking these symbiotic partnerships another level through their environmentally conscientious designs are projects like the Snæfellsstofa Visitor Center for Vatnajökull National Park, adjacent to Snæfell Mountain in Egilsstaðir.

As the winner of an open competition, the project was designed by Icelandic architecture firm ARKÍS architects and opened in June of 2010 as the first BREEAM certified building in Iceland (Figures 86-88). The project is also VAKINN certified Gull [gold], an environmental rating system for tourist sites in the nation. Active in several other open architectural competitions and infrastructure projects supporting the nation's natural wonders, ARKÍS is one of the nation’s leading firms supporting sustainable tourism and their projects include the Ófærufoss, a viewing platform in Vatnajökull National Park, and a small pavilion featuring restrooms and a café near the Hvítserkur at Hunafloi Bay.

Figures 86-88. With a low, sloping profile in section, visitors ascend from the parking lot into the visitor center and the educational axis terminates in a cantilevered volume overlooking the glacial landscape.

The building is entirely powered by hydro-electric energy and features a range of local materials and architectural inspirations: board-formed concrete with lava rock aggregate, a turf roof, and gabion retaining walls with local igneous rock (Figure 89).7

Figure 89. The concrete casting system employed at the visitor center creates a series of repetitive bands throughout the building that reference both the wooden rainscreen on the exterior and the tephra layers of the surrounding landscape.

The building's X-shaped configuration allows the staff areas and education axis to operate independently, intersecting at the café that has open views across a reindeer-filled meadow. The region was identified as a reindeer sanctuary in 1975, protecting the descendants of the first Norwegian reindeer brought to the island in 1787.

Figure 90. The freestanding storage rooms, identified in green and yellow on the plan, provide a windbreak for the visitor center.

Although an environmentally monitored area for nearly four decades, the National Park was established in 2008. At nearly 14,000km², it is the largest protected natural site in Europe and with such a sprawling area, the park has a series of visitor centers, located in Ásbyrgi, Skirðuklaustur, Höfn, Skaftafell, and Kirkjubæjarklaustur, as well as ranger stations in Snæfell, Hvannalindir, and Kverkfjöll. The region is also home to a number of other historical sites, including the ruins of a 15th century Augustinian cloister and a rare stone home, Skriðuklaustur (Figure 91).

Figure 91. Once home to writer Gunnar Gunnarsson (1889-1975), Skriduklaustur is now a center of culture and history for the region.

Within the Snæfellsstofa Visitor Center, there are static and interactive exhibits about the flora and fauna of the park, the glacial elements related to the Earth's water cycle, and the region's geological history (Figure 92). The center provides a useful background for understanding how and why the lush landscape of eastern Iceland, with its heaths and bogs, is so different from the rest of the island and, consequently, supports a very diverse ecosystem. Like many of the other built attractions in the nation, the visitor's center is seasonal: it is open from mid-April through the end of September, but is available by appointment in the wintertime.

Figure 92. In addition to the educational mission, the visitor center provides a welcome place to escape the unpredictable rain and wind that can plague the area even in the summer months.

The Future of Tourism in Iceland, at a glance

The documentary The Future of Hope (2010) underscored Iceland’s need to think local and act global.8 Although the nation has plentiful, renewable energy, with nearly 90% of their geothermal power released into the atmosphere, the nation is mobilizing to empower small businesses and agricultural production. The latter will be essential to a sustainable future since an eruption of Kalta looms: as Reykjaviík dimmed its street lights to allow visitors and locals an unimpeded, urban perspective of the Northern Lights, the Icelandic Meteorological Office raised alert status to ‘yellow’ on Friday September 30 based on elevated ‘seismic unrest’ in the area. The eruption of Eyjafjallajökull in 2010 impacted air travel for more than twenty countries and put Iceland’s food crisis in the spotlight. A major eruption and the resulting impacts on air quality could cripple a nation that feeds its inhabitants, and visitors, primarily with imported goods. The slow food movement is taking hold in the northeast part of the nation and around the southern portion of Iceland: fields of greenhouses powered by geothermal energy now dot portions of the landscape (Figure 93). As tourism rises and Iceland’s natural wonders threaten dramatic shows, it is clear that rampant hotel construction and visitors meandering from marked paths are just a few of the challenges that face the island (Figure 94).

Figure 93. A view in one of the geothermal greenhouses of Hveragerði.

Figure 94. A hand-painted sign in the Hverir geothermal area near Lake Mývatn warns, “it only takes one set of footprints for thousands to follow. Stay safe- respect nature.”

Since a primary focus of my experiential research sponsored by the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship is cultural heritage tourism, it seemed apropos to conclude this post, and my time in Iceland, with a few practical notes and suggestions for any readers who hope to visit the island:

- If you have the time and resources, spend at least two weeks in Iceland. A brief, jet-lagged layover will not provide you with the time or energy to fully explore and although the capital region is a rich and fascinating place, explorations farther afield are not to be missed. Some tour agencies and books advertise 7-day trips around the Ring Road but this means you will stay on the main route, trailing behind tour buses, and miss many of the unparalleled scenes along secondary roads.

- Entrepreneurs are capitalizing on tourism: research any bookings before you make them and it is worth supporting the tour agencies that are dedicated to carbon neutral operations and community improvement initiatives.

- Look for the ‘Whale-friendly’ stickers on restaurants to ensure that the business operates in accordance the ethical fishing standards of the International Fund for Animal Welfare and the Icelandic Association of Whale Watchers.

- With the exception of Þingvellir National Park, skip the Golden Circle: the varied waterfalls of the northeast (e.g. Dettifoss and Selfoss) or south (e.g. Seljalandsfoss and Skógafoss) provide better hiking trails and closer views while the thermal fields of Myvatn or the Reykjanes Peninsula are more expansive, and less crowded.

- If you rent a car and intend to traverse any portion of the Ring Road, the ash and sand insurance is well worth the fee to ensure that you are protected against damage from the prevalent storms around the volcanic island. It is also well worth renting an AWD vehicle: this is not explicitly for driving the Highland’s F-roads, although 4WD are the only vehicles legally allowed to traverse these roads. Some portions of the Ring Road are gravel and very few areas have shoulders so an AWD vehicle will ensure a bit more stability and the elevated seats substantially increase visibility on the winding roads.

- Enjoy a trip to the Blue Lagoon but make sure you go to a community-based geothermal pool to meet locals and get a more authentic experience of thermal bathing culture. Entry to the pools is extremely reasonable and your entry cost often helps support swimming lessons for locals of all ages; Icelanders are sharing communally-funded resources with tourists and so local pool patronage can be a small way to give back to their generosity.

- Finally, be mindful of the posted signs and warnings. It is a living landscape that can be quite dangerous for humans when it comes to fissures, hot pots, and thermal phenomena. From a conservation standpoint, although Iceland’s landscape looks rugged and resilient, there is a delicate ecosystem at play. Leaving marked paths can result in footprints in the ash that compress the soil and cause irreparable damage. The moss growing on the volcanic rocks (Cetraria islandica) is a global rarity and damage to a small portion can cause a larger section of the interconnected biomass to rapidly degrade.

Bibliography

30 Sustainable Nodric Buildings: Best Practice Examples Based on the Charter Principles. Oslo: Nordic Innovation, 2015. http://nordicbuiltcities.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Katalog_www.pdf.

Bateman, Henry. "Future of Hope." 75 minutes. Iceland: Future of Hope Ltd., 2010.

Jóhannesson, Dennis. A Guide to Icelandic Architecture. Translated by Bernard Scudder. Edited by Jóhannesson Dennis Reykjavík: Association of Icelandic Architects, 2000.

Þórbergur, Þórðarson. Í Suðursveit. Reykjavík: Mál og menning, 1984.

1 Dennis Jóhannesson, A Guide to Icelandic Architecture, ed. Jóhannesson Dennis, trans. Bernard Scudder (Reykjavík: Association of Icelandic Architects, 2000), 162.

5 Much of the information for this section comes from the highly informative display boards and visitor brochures found in the cited museums.

6 Þórðarson Þórbergur, Í Suðursveit (Reykjavík: Mál og menning, 1984), 47.

7 30 Sustainable Nodric Buildings: Best Practice Examples Based on the Charter Principles, (Oslo: Nordic Innovation, 2015), http://nordicbuiltcities.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Katalog_www.pdf. 89.

8 Henry Bateman, "Future of Hope," (Iceland: Future of Hope Ltd., 2010).

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top