-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Awe-chitecture and Ornamentation of Gothic Cathedrals

'Deyemi Akande is the 2016 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

If you, like me, respond fairly well to the beauty of intricacy, then you can imagine the sensation that one experiences when greeted by the interior of a Gothic Cathedral—When I entered the upper chapel of Sainte Chapelle, I needed to sit for a while to gather myself and process the visual information—the beauty of stained glass, mortar and purpose was so brilliantly delivered and perfectly articulated by the grammar of ornaments. I intermittently asked myself ‘What had possessed these people to birth such beauty?’ This beauty is the same everywhere I went. It is a beauty made apparent and possible only through ornamentation. The coming together of the ornate elements at such grand scale makes a truly bold statement for the purpose of ornamentation in architecture irrespective of age and style.

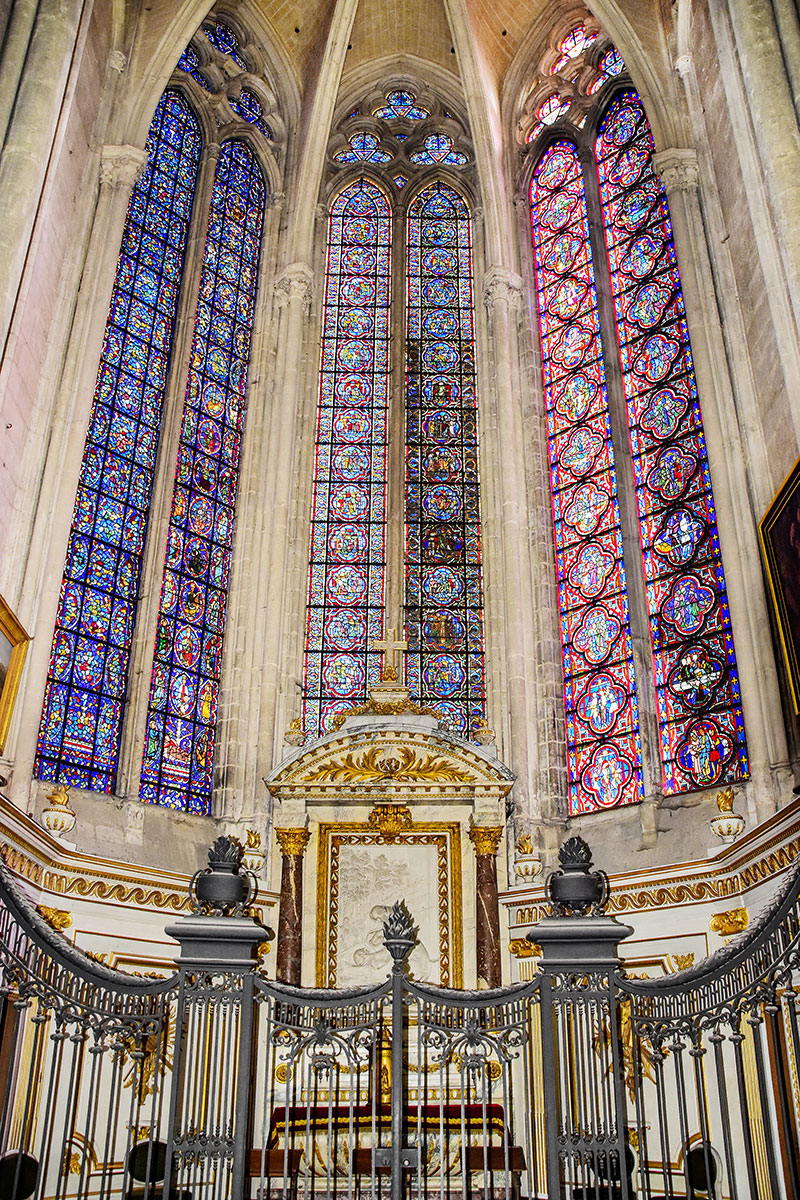

Figure 1: A view of the upper chapel in Sainte-Chapelle showing the spectacular line up of stained glass. Also in view is the apse, vaulted ceiling and the relic platform.

Figure 2: Details of the reliquary in the upper chapel of Sainte-Chapelle. Notice the icon of the crown of thorns symbolically situated on the relic platform.

Figure 3: Close up of details on the relic platform inside Sainte-Chapelle.

Figure 4: Vaulted ceiling of the upper chapel in Sainte-Chapelle with a hint of the pointed tips of the arches. The surface of the vaults are decorated with stars.

Figure 5: Decorated shrine with twisted baroque style column in the Notre Dame Cathedral of Amiens.

Figure 6: Detail of the capital and twisted column in Notre Dame Cathedral of Amiens.

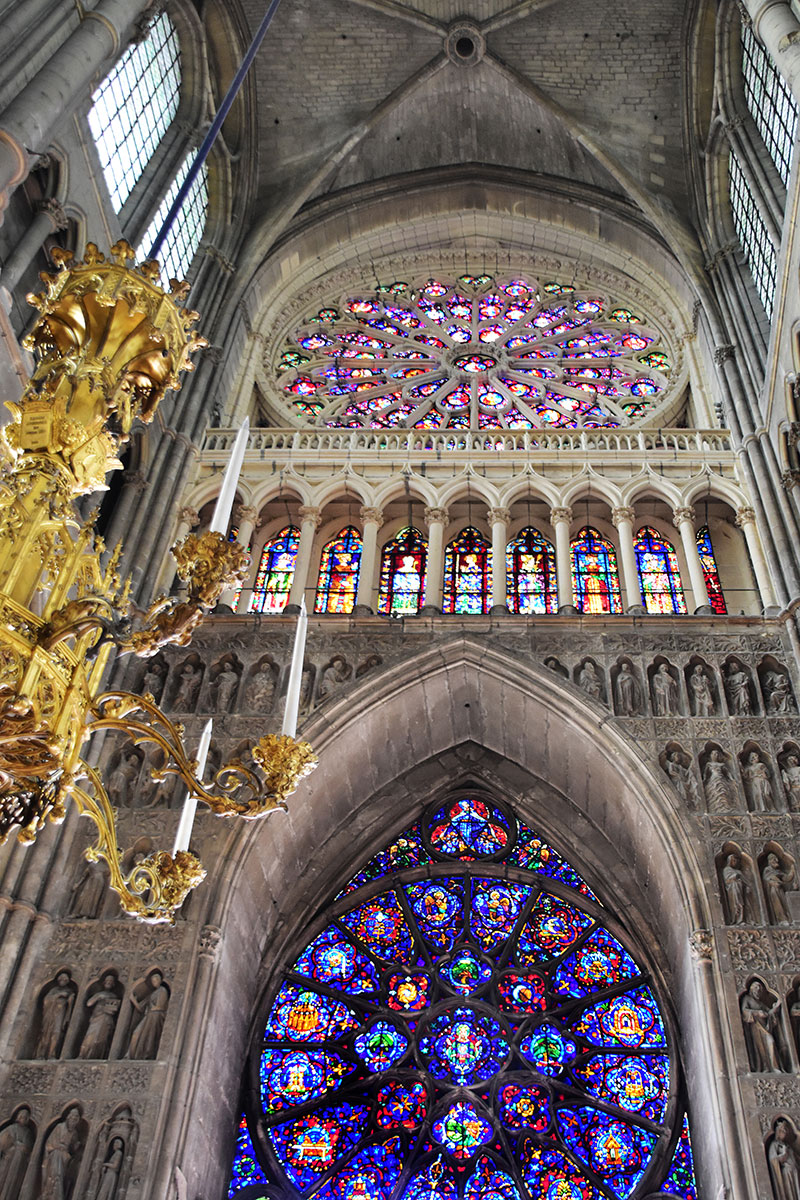

Figure 7: The reverse side of the front façade of Notre Dame Cathedral of Rheims showing the Small Rose window and the Great Rose in the upper part. Notice indented figural elements on both flanks of the lateral door.

Figure 8: Statue of Saint Nicasius who in the early 5th century chose the final site to build the early basilica dedicated to the Virgin Mary. He was killed by vandals at the step of the cathedral in 407AD.

Figure 9: Two views of the richly ornamented cathedral organ chest in Strasbourg Cathedral. The organ chest was constructed in 1489 by Frederic Krebs d’ Ansbach. The heavily decorated pendentive key-stone is circled in white. See details in Fig. 10

Figure 10: Details of the pendentive Key-stone feature Samson and the lion theme from the famous Biblical story.

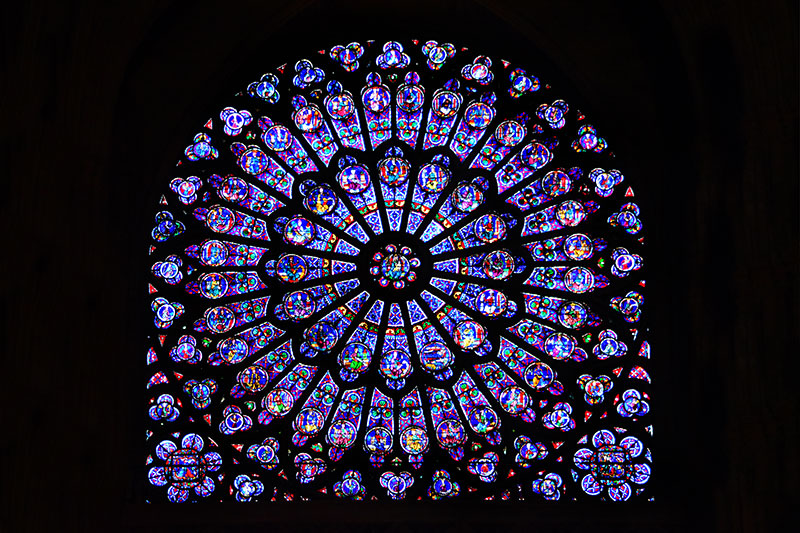

Figure 11 The North Rose Window of Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris feature Old Testament themes but also captures some from the New Testament.

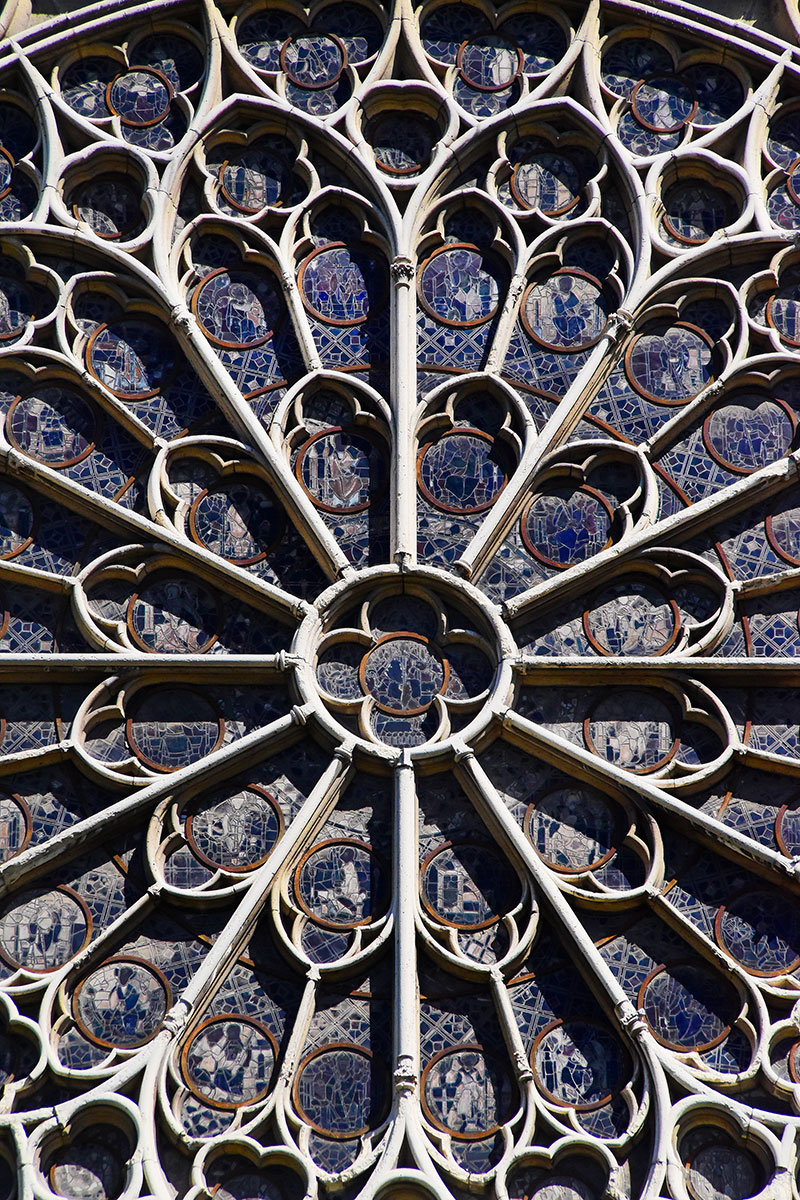

Figure 12: Close up showing ornate details of one of the Rose Windows on the Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris.

Figure 13: The Martyrdom of St Lawrence, a brilliant piece found in the northern side of the transept at Strasbourg Cathedral. The artistic delivery is mixture of Baroque and Gothic styles.

You think you know the meaning of ‘awe’ until you come in contact with a Gothic Cathedral. When your eyes meet the meticulously detailed architectural skin of a gothic piece, your notion of the word is very quickly redefined. Awe was what I felt when I saw Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. You are taken completely by its imposing size and medieval allure, but most importantly, the intensity of the ornamentation on the building is beyond belief—well so I thought, until I saw Rheims Cathedral and then Notre Dame Cathedral of Amiens and then Strasbourg Cathedral. You can imagine how I continued to recalibrate my idea of the meaning of the word—Awe. Your eyes open up, your head is raised on impulse to capture the size of the work, then you unconsciously begin to calculate in your mind how long and hard it was to create this magnum opus—nothing truly beats the rush. Little wonder that several hundred years after their creation, they still welcome millions of people to their isles and nave—what wonder Gothic Architecture is.

Figure 14: Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris. Western Façade. A multitude of people visit the cathedral every day.

Figure 15: Details of the Portal of the Last Judgement on the western façade of Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris. Christ as the centre piece enthroned flanked by angels holding the cross, the nails and the lance used during the passion. On the archivolts are a large number of saints.

Figure 16: The South-western Tower of Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris photographed from the Western end of the cathedral.

Figure 17: Details of the ornamentation on the tip of the South-western Tower. Notice the gargoyles and other ornate elements.

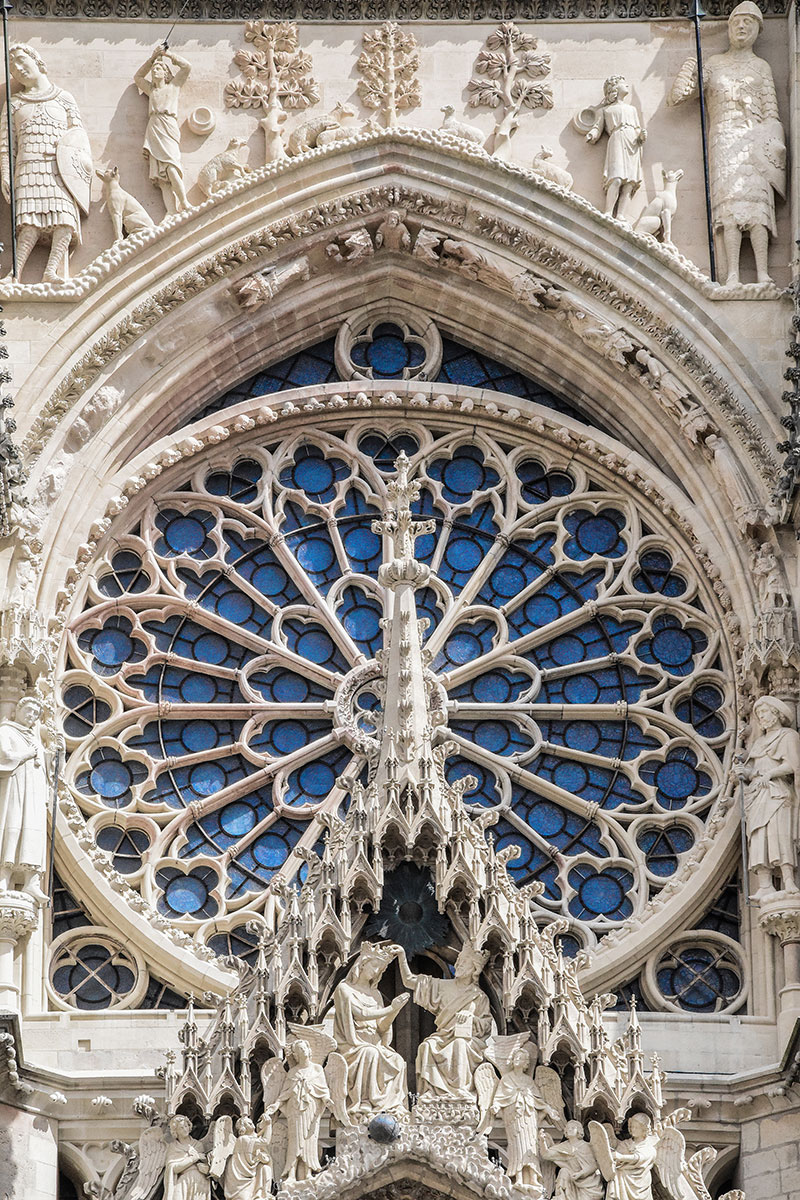

Figure 18: The heavily ornate Rose window at the Saint Etienne portal on the western side of the cathedral. Notice the Trefoil & Quatrefoil elements used in the design of the window segments. Also notice the design elements on the pinnacle and the sculptural figure atop the pediment.

Figure 19: Details of one of the sculptural pieces on the right side of the central portal. Here an abstracted mix of human and beastlike form is melted together in a type of frenzy. This is a slice of the scenes of agony and misery in the hades.

Figure 20: The western (front) façade of Notre Dame Cathedral in Rheims showing the central portal, the Small Rose window of the Litanies of Mary and the Great Rose.

Figure 21: Close detail of the western façade of the Notre Dame Cathedral in Rheims showing the central portal, Small Rose window and the Great Rose.

Figure 22: Details of the decorative gable piece with Mary’s Coronation as theme and the Great Rose as backdrop.

Figure 23: Detail of the Western Façade of Notre Dame Cathedral of Amiens showing a finely ornate Rose window and the kings’ gallery.

The Viennese architect, Adolf Loos is famously credited with the construct ‘ornament is crime.’ In his 1908 treatise, he presents ornaments as an invention of the primitive man; an invention he believes must ultimately give in to the superiority of the emerging machine age. If this ideology, however controversial, is still anything to go by, then for the next twelve months, I consider myself a primitive criminal as all I will do will be to glorify the ingenuity of middle age ornamentation and craftsmanship on selected cathedrals in Western Europe.

For a couple of years now I have been deeply interested in sculptural arts and architecture and as a result I have had the opportunity to see fine samples of the synthesis of both disciplines. Nothing however could have prepared me for the Gothic Overdose I am now experiencing in France through the wonderful opportunity presented to me by the prestigious H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. I am extremely grateful for this rare chance that will allow me separate myself from the tedium of daily life and spend time in the presence of majestic cathedrals to contemplate on the discipline of architectural history. As I have already hinted, my journey starts in France and will take me through Spain, United Kingdom, Germany, Italy and Greece. The fellowship will also permit me to make a stop in Egypt where we have arguably the earliest examples of the synthesis of art and architecture. There, I hope to see and physically examine the admixture of architecture and art in the ancient cities. My choice of Western Europe is premised on the fact that it presents me with some of the oldest and most preserved examples of Gothic expressions.

Figure 24: Details of sculptural ornaments from the central portal of Notre Dame Cathedral of Amiens.

Figure 25: View of Strasbourg Cathedral from the Western end. The cathedral is so huge that it poses a major challenge to getting a full view photograph of the building. Notice the size of the people at the base of the photo in ratio to the building.

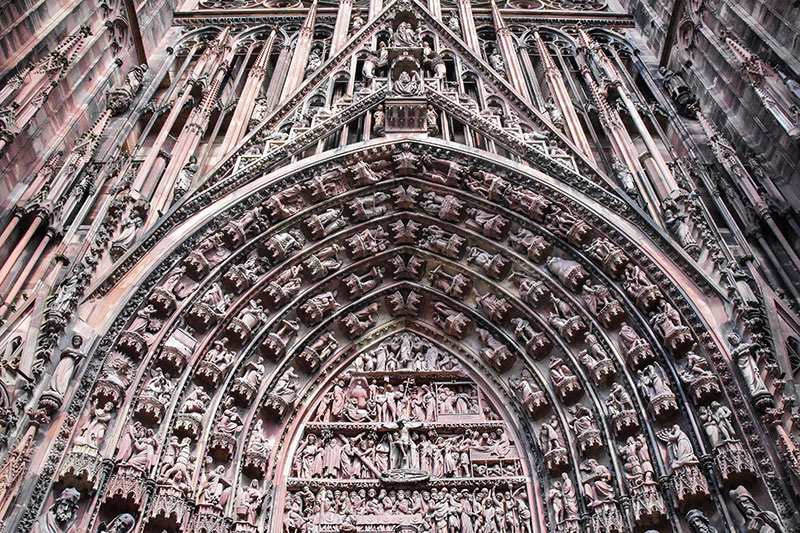

Figure 26: Detail of the central portal of the Western façade. Strasbourg Cathedral.

QUESTIONING ORNAMENTATION

Before I get into the summarised accounts of my experience at the different cathedrals, an array of questions have plagued my mind since I got on my flight in Lagos. Answering these questions are fundamental to my assessment of this fellowship year. As I write, I continue to churn them in my mind with little luck so far. I am optimistic however that a meaningful response to these questions will be revealed as the weeks go by.

As some pro-modern ideologists may challenge the relevance of a study into ancient ornamentation, I myself, in spite of my intense desire to query this aspect of history, find that I am beside myself asking similar questions. I must be quick to submit that this is healthy; for only in this state of chronic inquisitiveness are we to find fresh understanding that will move us further from where we currently reside.

To what purpose do we study history—particularly that of architecture? And in this instance, ornamentation. What need is there for us in the postmodern world to belabour our minds with the art of medieval beautification? What wisdom does this ancient knowledge offer us? And by wisdom, I refer to the type that counts for something practical in this current rumbustious time where there is now technically no right or wrong—just popular. Can the study of ancient architectural ornamentation bring any eureka moment that may significantly affect our discipline today? Something is certain to me though—it is that ornamentation is a language. And like any ancient language, learning and knowing it directly opens up a world of knowledge that often bare positively on the present. I am thus eager to know what this language will reveal to me. As I ponder these, I am in the meantime arrested by these words from John Ruskin as quoted in Connelly (2015) as a kind of commission:

Go forth again to gaze upon the old cathedrals front, where you have smiled so often at the fantastic ignorance of the old sculptors: examine once more those ugly goblins, and formless monsters, and stern statues…; but do not mock at them, for they are signs of the life and liberty of every workman who struck the stone; a freedom of thought, and rank in scale of being, such as no laws, no charters, no charities can secure; but which it must be the first aim of all Europe at this day to regain for her children.1

Perhaps this whole venture is to redirect our attention to Freedom in Architecture.

Figure 27: Decorated vaulted ceiling in the lower chapel of the Sainte-Chapelle

Figure 28: The Gable of the South transept of Rheims Cathedral. Atop the gable is a statue of Sagittarius with a drawn bow.

Figure 29: Stained Glass windows overhangs one of the transept chapels.

Figure 30: Close up detail of one of the Jamb figures at Rheims Cathedral.

SHORT NOTES ON THE CATHEDRALS

Every cathedral has its own story. Stories that span many decades. In my naivety I had nurtured the thought of giving a detailed oratory of the history of each cathedral and every major detail to be seen on the different structures. This was immediately dashed the moment I saw Strasbourg Cathedral. The sheer size and amount of ornate elements are such that I can only manage very short notes in this article. Perhaps at a later date, I may have a separate opportunity to articulate in greater detail what I saw and feel is worthy of discussion particularly from the perspective of a non-European.

To build a cathedral is certainly no trifling work. Many of the cathedrals I already mentioned here spanned decades, sometimes centuries to complete. The very fabric of the building is a representation of the people and their religious conviction and resolve.

Cathedral Notre Dame de Paris is a prime structure among equals. It stands regal on the spot where three earlier churches once stood. What we see today is largely the 11th-century dream of Maurice de Sully (then Bishop of Paris).

The cathedral features three prominent portals on its western façade—The central being the largest and so generously adorned with sculpture is known as the portal of the Last Judgement. Just above the portals are a prominent line of statues—twenty eight in all. These figures were erroneously thought to represent the past kings of France when in fact they are of the twenty eight ancestors of Jesus from Jesse through to Joseph as listed in St Matthew’s gospel.2 The consequence of the error was to act against the cathedral during the French revolution as the people thought them to be the very symbol of what they fought against. Needless to say, the statues were pulled down but for such luck on the part of the cathedral, fragments of it were hidden and rediscovered in 1977. They are now part of a permanent exhibition at the Cluny Museum alongside other original sculptures from the Notre dame.

Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris is also lucky with treasures and it is the resting place for several valuable items assembled over a long period but decimated during the French revolution and again during the 1830, 1831 riots. Perhaps the most important item that rests in the cathedral’s keep is the ‘Crown of Thorns’. Said to be the very crown put on the head of Jesus by the Roman soldiers at the crucifixion. It is obviously impossible to ascertain the authenticity of this particular crown as a couple other ‘Crown of Thorns’ did surface all around Europe. Nonetheless, the enigma and influence of this relic is second to none. The relic was acquired by King Saint Louis who brought (carried) the item himself to Notre Dame on the 18th of August 1239. The ‘crown’ was later placed in Sainte Chapelle but would later be returned to Notre Dame where it is displayed occasionally for Christian worship and veneration till today.

Figure 31: Detail of the sculptural work on the central portal of Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris. Here in the Last Judgment, the arch angel is seen to the left and a demon-like figure to our right jostling for souls as their spiritual standing is weighed on a scale.

Figure 32: A portion of the gallery of ‘kings’ on the western façade of Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris.

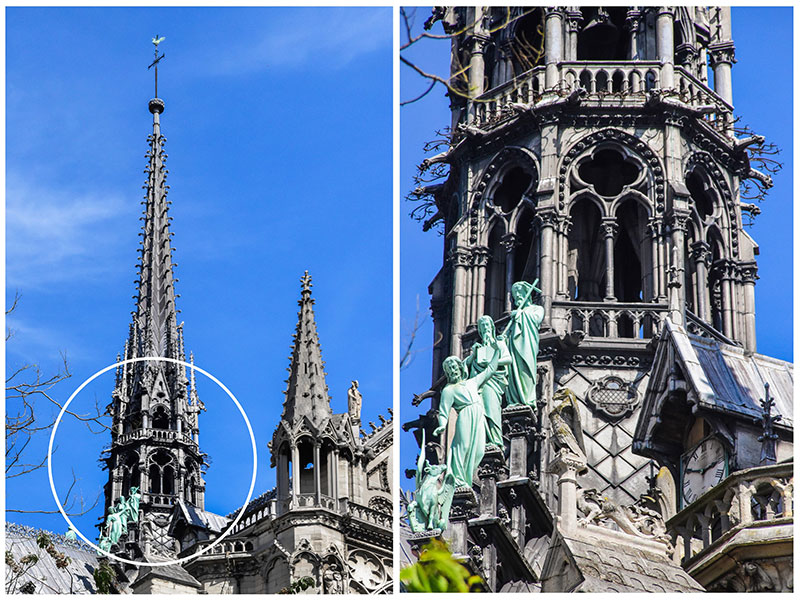

Figure 33: Two views of the Spire over Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris. The area marked in white circle is shown in greater detail on the photo to the right.

Figure 34: Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris towers.

Figure 35: A view of the Cathedral’s vaulted ceiling showing the keystone at the centre of the transept. The keystone is decorated with the image of the Virgin Mary and a child surrounded by stars and with a crescent moon at her feet.

Figure 36: A monument in honour of the Virgin Mary at the East garden of Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris. Area marked in white circle is shown in greater detail in the right photo. Notice the use of the Trefoil symbol – a very popular symbol in religious iconography.

Sainte Chapelle is at the heart of the Palais de la Cite—the central area of Paris with a long history of royal residence and site of administration. The breath taking Rayonnant Gothic style chapel is still one of the finest examples of the marriage of stone and glass in France. Built by King Louis IX (later Saint Louis) from 1242 to 1248, the structure is now cramped in the same compound with the Ministry of Justice. It is a two-tier structure with the lower chapel meant for the palace staff to worship while the upper level fully cladded in stained glass from the 13th century was designed as a reliquary to house the relics of passion and for the use of the king, his close family and officiating clergy.

The relics of passion are generally items associated with the Passion of Christ. They usually include the Crown of Thorns, nails from the crucifixion, and fragments of the original crucifix. The Holy Relics as they are referred to originally belonged to the emperor of Constantinople since the early times but was acquired by Louis IX of France to bolster the religious reputation of France. This must have worked to some degree as France was generally regarded to be the second Jerusalem in medieval Europe on account of the Holy Relics. One record has it that the most prestigious of these relics—the Crown of Thorns—was procured in 1239 at a sum far greater than the amount used to build the Chapel itself. Through the years, Sainte Chapelle stood as a symbol of the link between royalty and divinity. It, like many other medieval edifices, suffered immense damage and neglect but regained its glory through waves of restoration from early 1840s.

At Sainte Chapelle’s upper chapel, an interesting feature caught my eye. It is understandable that visitors to the chapel will spend most of their time looking up obviously to appreciate the wonder of the orchestration of light offered by the 15 surround stained glass with over a thousand depicted scenes from the Bible. The thing is looking down also offers quite a handsome reward as the floor of the upper chapel is laid with beautiful and well ornamented paving tiles showing vegetal, animal and even architectural motifs. It was tough getting the folks out of the way in order to get a photograph. The reason? Simple, they were all looking up.

Figure 37: A view of the east end of the lower chapel – Sainte-Chapelle.

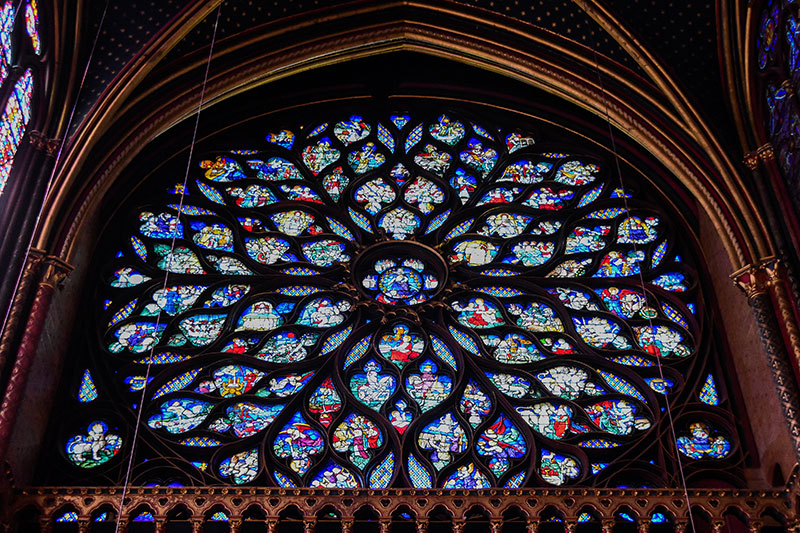

Figure 38: The Western Rose window in the upper chapel of the Sainte-Chapelle. It is 9 metres in diameter and is composed of about 89 panels.

Figure 39: The floor paving tiles showing vegetal and architectural motifs.

Like Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris, Rheims Cathedral presents no less a wonder to behold. The current building, like the Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris and many other religious buildings of the world for that matter, sits on the site of two former basilicas. The cathedral boasts of hosting the coronation ceremony of twenty five kings of France from Louis VIII the Lion in 1223 to Charles X in 18253—that is a remarkable span of six hundred years! King Clovis was baptised by Saint Remi himself within the precinct of the cathedral in 498 AD. A floor plate marks the spot where this happened. The plate says, Ici Saint Remi Baptisa Clovis Roi Des Francs—Here Saint Remi baptised Clovis King of France.

The present site of the cathedral was chosen by Bishop Nicasius (later Saint) who built a basilica in honour of the Virgin Mary in the 5th century. The Bishop was later martyred by vandals at the very steps of the cathedral entrance in 407 AD. One will not miss the very emotive statue of the founding Bishop and Saint, Nicasius, strategically placed between angels on the reverse side of the front façade. The figure shows the decapitated bishop with his mitred head in his hands. This symbolic icon used to represent decapitated martyrs is a rather common feature on cathedral walls and perhaps at a later date I will write a feature on the headless figures that dot portals and cathedral walls all over. In 1210 fire gutted the second church that was an outstanding 19th-century enlargement of the first basilica orchestrated by Archbishops Ebbon and Hincmar. The foundation stone of the third and present church was laid by the Archbishop Aubry de Humbert on the 6th of May 1211, exactly one year after the fire.4

On the west end, just behind the figure of Saint Nicasius, one will notice two rose windows. The one that sets as backdrop for Saint Nicasius’ statue is known as the Small Rose Window of The Litanies of Mary while atop that is the Great Rose. The larger Great Rose window features a brilliant array of representations that include the twelve apostles, the 24 angels, musicians and seraphins, six kings of Israel and a centre piece on Mary. Soft light passing through the coloured glass before noon presents the interior west end with a symphony of pleasing light.

On the exterior, atop the central doorway before the Great Rose window is a sublime sculptural rendition of Mary’s coronation. Mary is here seen being crowned by Jesus. They are both flanked by angels that look unto the Mother and Son. The apparent difference in the colour of the stone on this gable suggests that this work is a copy of much later date. In all, the array of sculptural and ornamental elements presented on and in Rheims Cathedral featuring different theological and abstracted themes from the Bible clearly makes the cathedral an example of Gothic excitement and an architectural piece worthy of one’s time and mind.

Figure 40: A floor plate in the nave of Rheims Cathedral marking the spot where King Clovis was baptised by Saint Remi.

Figure 41: Close up detail of Mary’s Coronation as seen on the gable over the central portal of Rheims Cathedral’s western façade.

Figure 42: A Gargoyle

Figure 43: The famous angel of the smile – Rheims Cathedral

Figure 44: Arched vault ceiling in Rheims Cathedral

Figure 45: Wood work. An ornamented pulpit inside the Rheims Cathedral.

You are very likely to access Strasbourg Cathedral through one of the very narrow streets of Strasbourg and nothing will prepare you for the site you will behold as you burst free into the wide space that hosts the uniquely deep brown coloured structure. I was literally stopped in my tracks as I emerged from a corner to the monstrously huge building. Beyond the initial shock, what remains is pure beauty and wonder. Again, the words brusquely escaped from my mouth; what had possessed these people to birth such beauty? Particularly in the age well known to be the ‘Dark Age.’ Beside the oddly dark brown colour, nothing else about this cathedral was dark. Standing now at roughly 142 meters at its highest point (the Spire) Strasbourg Cathedral is the perfect example of the impossibility of the Dark Ages made possible. The building was in continuous construction for almost 800 years with several parts of it being added and removed at intervals with the intent of achieving the highest possible glory for the house befitting of God. Work started around 1190 and till 1880 parts of what we see today were still being added.

One unique and monumental feature in this cathedral is the astronomical clock situated on the south eastern end of the building. As Roger Lehni puts it, it is a combination of arts with science and technology.5 Still very renowned, the original work on the clock started in 1547 by architect Bernhard Nonnenmacher and was continued by other craftsmen between 1571 and 1574. Hans Uhlberger, the architect of the cathedral completed the chest and painter Tobie Stimmer embellished it.6 The clock still provides astronomical readings while the mechanical figures announce the days and passing hours.

The organ is also worthy of mention. It is a richly ornamented piece and suspended meters above ground. The organ’s pendentive key-stone is decorated with Samson and the lion. It is an impressive piece of craft when one considers the aura it commands with some moving parts that can be set in motion from the organ loft. See Fig. 9 & 10

Next I will proceed to Notre Dame Cathedral in Chartres, Saint Gatien Cathedral in Tours and then to Saint Denis Basilica—the final resting place for many kings of France.

Figure 46: Western façade of the Strasbourg Cathedral showing the central portal.

Figure 47: The astronomical Clock in the southern part of the transept of Strasbourg Cathedral.

Figure 48: Figural and decorative elements on Strasbourg Cathedral.

Figure 49: Figural and decorative elements on the wall of Strasbourg Cathedral.

Figure 50: A humanoid gargoyle on Strasbourg Cathedral.

ORNAMENTATION AND THE CITY

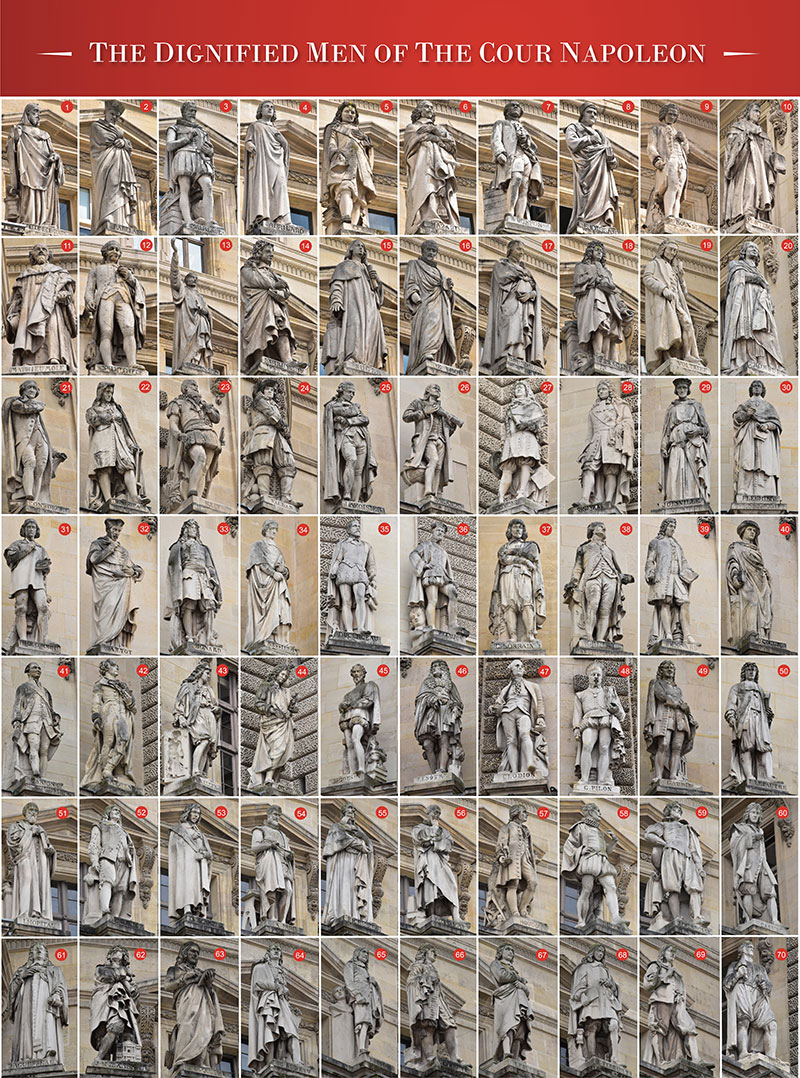

Though not included in my original itinerary, I took some time off to visit the Louvre Museum in Paris. I must allow myself this fair indulgence for by all standards of reason, it will be nothing short of a capital sin for anyone inclined to the arts in whatever little manner to come to Paris and not see the Louvre. The Louvre is stately and indeed commands the presence worthy of a palace. The history and content of this outstanding complex is out of my scope here but this I must share—anyone who responds to architecture in any little way will most certainly find him or herself looking up always when in France. This is on account of the continuous presentation of intensely engaging architecture which are either almost occluded by the noise of modernity or finely preserved in a space of its own. So, looking up was what I did. And there, I was drawn to the row of statues that line the Cour Napoleon in the Louvre, reminiscent of the statues of saints that line the colonnaded piazza of the St Peter Basilica in Rome. These figures grace the terrace of the Cour Napoleon in a way that gives the arena ornamental value. The statues live and grow on the building adding a kind of appeal that cannot be overlooked. In all, seventy dignified portraits of great men, finely crafted and in character, immortalised in stone. Beyond the captivating and sublime beauty of the Louvre and the now iconic pyramidal structure that dots the Cour Napoleon, these works are deserving of notice. They represent the cream of the nobility of early France. I now like to call them Les Hommes dignes de la Cour Napoleon.

Figure 51: The Dignified Men of the Cour Napoleaon. A photo montage showing the statues that line the Cour Napoleon in Louvre. They include great names like Sully, Colbert, Vauban, Buffon, Rabelais, Grety, G. Pilon, Duperac, Perrault, Houdon, Richelieu and so on.

Figure 52: Details of the Pavilion Turgot’s ornamentation. Louvre Museum. Paris

Figure 53: Details of the Pavilion Colbert’s ornamentation. Louvre Museum. Paris

Figure 54: A view of the Crystal Pyramid in the Cour Napoleon, Louvre.

The material culture of France is that wrought with ornaments. Ornamentation is the major ingredient for the construction of value in Paris and Parisians resonates this sentiments for ornaments even in modern times. Everywhere you turn, one notices the result of an underlining philosophy of adornment. The vibrancy and texture that ornamentation brings is very potent and certainly not hard to find in France. Perhaps not in the same manner as the middle ages but certainly with the same intention—to tell, to preserve and to promote a story but probably more importantly, to add meaning to plain matter. As Jimmy Shen once said, “The more a thing is designed the more meaning there is contained within it.”

Figure 55: White fumes from jet trails crisscross in the skies of Paris in a way that it adorns the plain blue sky. The vivid lines draws one’s attention and speaks to the fact that ornamentation adds value and value draws attention.

Figure 56: A couple in the full glare of passers-by braves the cold wind dancing the day away beside a heavy traffic footpath. Such unique scenes creates a rather textured and ornamented urban fabric in Paris. The composition is further enhanced by the passing boat in the background that carries a flag of France and features a somewhat apt name that compliments the whole flash event - ROMANTICA!

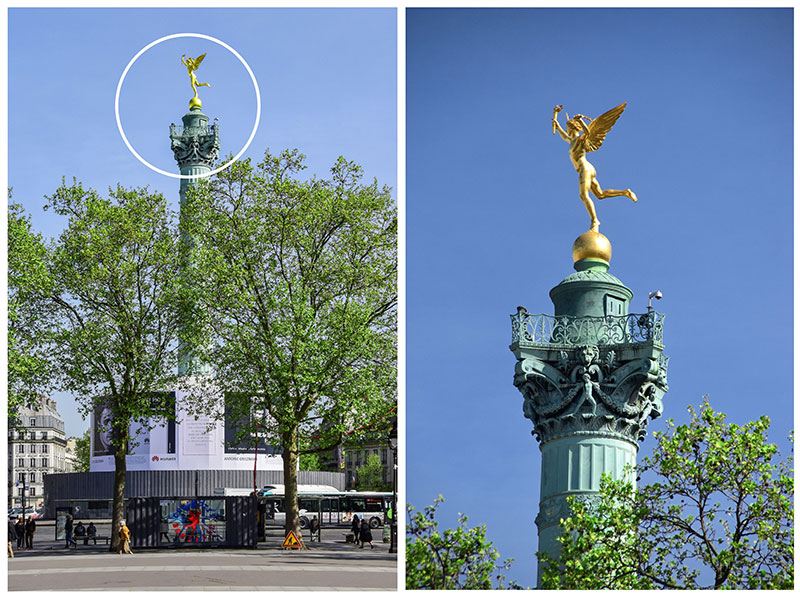

Figure 57: Colonne de Juillet – The July Column. A monument that commemorates the 1830 July Revolution. This piece beautifully accentuates the Bastille Square in Paris. The pinnacle piece is a golden winged male figure.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top