-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Ruin as Ornament

Deyemi Akande is the 2016 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

I am not from a culture that values ruined objects. We see and relate to them more as an eyesore than vestiges of a great past. In fact, culturally, we are obligated to repair, replace or remove ruined objects. As a historian, who is also Yoruba, being in Greece presents a chronic and well-founded conflict within me. Thankfully, culture alone does not inform my actions. While I confess that at first glance Greece fatigued me and it was tough for me to relate to the ruins, however historic and revered, it will take more than cultural indoctrination to prevent the uncontrollable high you feel when the thought crosses your mind that Socrates may have touched this very column I am now touching.

To untrained minds, a ruin is exactly what it is—devastation and decay. It should have no visual appeal and no beauty; at least not the type that will draw us to it. Ruins should have no function and no useful value to us in the present age where our taste and needs have morphed over time to such extent that an ancient piece of jewelry, for example, is now so dated and useful only in an archaeology show-and-tell class or perhaps historic movie sets. Ruin, in basic terms, should mean the collapsed remnant of what was once great, now a deformed structure that no longer carries the appearance of majesty. In Greece, these suppositions are in fact not the case. Every year, millions of people give all to travel to see Greece’s architectural ruins. Ancient architectural sites, rank among the top three reasons why people visit Greece. Those ancient ruins have arguably become Greece’s most valuable asset and a very present evidence of the absence of a former glory.

Fig. 1: A vestige of former glory. The western façade of the Parthenon ("parthenos" in Greek). The temple of Athena, the Virgin goddess and protector of Athens showing its elegant Doric styled columns.

Fig. 2: Western façade of the Parthenon, temple of Athena. Practically all of its ornamented pediment has been lost to time.

Fig. 3: Closer details of the remnant of the pediment showing relics of the once glorious pediment sculpture.

Fig. 4: Details of the pediment showing remnants of its sculpture.

Fig. 5: Details of the fluted columns showing deterioration from age.

Fig. 6: Ionic capitals of the Erechtheion and the remnant of the pediment showing new marble from recent reconstructive restoration work.

The word ruin, as most architectural relics are called, has its origin in a Latin word ruina from ruere, which is ‘to fall’. I imagine this word to be quite apt for the description of architectural relics. For it is through the falling of an empire or a civilization that neglect comes to its structures and through neglect the gradual surrender to the powers of nature, which forces all that came from dust to return to dust. Thus, a ruin is not in itself an end but a mid-point in the cycle of life. After all, ruin is defined as the physical disintegration or the state of being destroyed. Speaking of definitions and the word ‘destroyed,’ it is important for me to mention for the record that not all ruins follow the romantic process of gradual disintegration described above. Many modern ruins remind us of another type of legacy, one with much violence and meaningless destruction. The character and posture of this other type carries a different kind of tension. Through it, the articulation of humanity’s bad judgments are ever so apparent. As I write, Aleppo, Mosul, and Raqqa all come to mind. I speak here of the atrocious destruction of architecture with a heavy heart, I will not belabour you to deviate too far off to mention the meaningless destruction of human life.

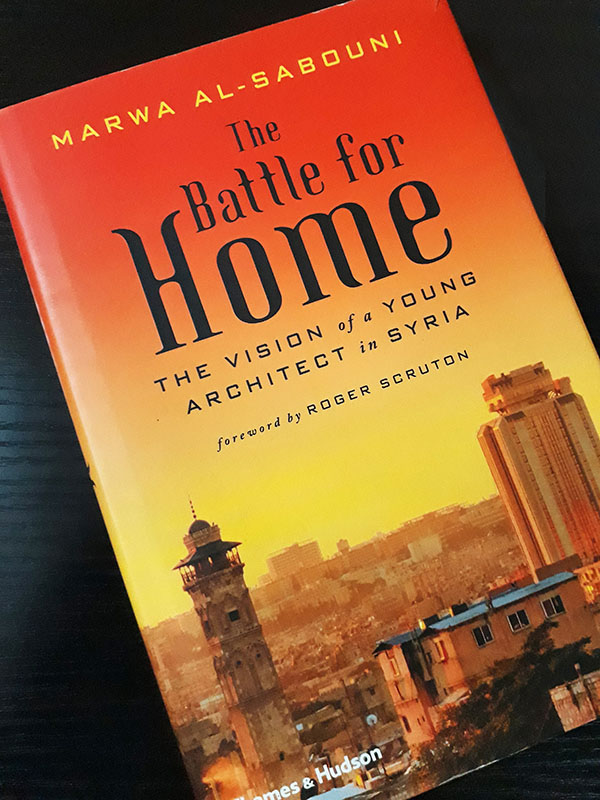

At the SAH 2017 Annual Conference in Glasgow, I was honoured to sit in a panel alongside extremely brilliant minds: Getty Research Institute’s Maristella Casciato, Abby Van Slyck of Connecticut College, Zeynep Kezer of Newcastle University, and Getty Conservation Institute’s Jeffery Cody. Dianne Harris of the University of Utah moderated. The panel discussed the challenges of practising architectural history in context of the current anti-knowledge political climate. Mr. Cody was so generously kind to give me what appeared to be his only copy of an excellent book ‘The Battle for Home’ written by Marwa Al-Sabouni, a young Syrian architect. I was immensely struck by her words as she described the utter tragedy of the reduction of Syrian built heritage to ruins. Early in her introduction, Marwa states that it is only through architecture that we see the point of view that is no one’s in particular and everyone’s in general. Buildings do not lie to us; they tell the truth without taking sides. Every little detail in an urban configuration is an honest register of a lived story.1 Indeed, the architectural ruins of Syria fully carries on its back, the mark of our collective actions or inactions.

Fig. 7: My copy of The Battle for Home by Marwa Al-Sabouni gifted to me by Jeffery Cody.

So what draws us to “rubble”? Perhaps the strong force behind architectural ruins are tied to the fact that they are concrete evidence of a past civilization and, a connection to our common quest for survival and a pursuit of greatness. Ruins are the vestige of an attempt at a life of substance by people before us. We are irresistibly attracted to them on account of a strong primal instinct we have to reach out to our ancestors and to touch the past. We humans have a burning desire always to connect with people like us either from a different place or time. The ruins are a proof of the triumph of the people of the past and to us, a glimpse of how the people of the future may see our legacy.

Fig. 8: The Erechtheion amidst hundreds of old marble slabs that were once a part of one temple or the other on the Acropolis.

Fig. 9: Marble columns, metal columns. Scaffolds now stand where the Naos used to be. The once sacred space now lays bare to all under the sun.

Fig. 10: The marriage of the old and the new. New marble is seen integrated with ancient marble on a column on the Erechtheion.

Fig. 11: The base of the Ionic columns of the Erechtheion on the Acropolis showing trimming ornamentation and the worn stylobate.

Fig. 12: The six beauties—caryatids—of the Erechtheion, worn with age but elegant nonetheless. Vitruvius in his treatise speaks of caryatids as immortalised forms of women (wives) from Caryae captured as slaves and presented in architecture as carriers of the weight of their shame for their state.

Fig. 13: Caryatids of Erechtheion. Closer details of the women of caryae in long robes.

Fig. 14: A view of the Parthenon, temple of Athena, on the Acropolis showing scaffolds from the restoration work. Notice the strong line of columns and the corner piece column showing clear signs of entasis.

Fig. 15: The Theatre of Dionysus.

Fig. 16: Arched walls of the Theatre of Dionysus.

Fig. 17: Details of the arched wall of the Theatre of Dionysus.

Fig. 18: Drums from old columns litter the grounds of the Acropolis.

Fig. 19: Piles of architectural elements and marble blocks from the ancient structures. The piles on the Acropolis are like a massive jig saw puzzle. The restoration teams are constantly trying to figure out what fits where.

Fig. 20: Drums from columns litter the grounds. Some from the past and some from the recent restoration efforts. The restorers being so meticulous will very easily discard any reconstructed architectural pieces that does not perfectly fit.

Ordinarily, I would see ruin only in its most superficial quality and would have delineated it as waste had I not come across the idea of the "afterlife of architecture." Afterlife of architecture is a concept that speaks to the remnant value and aesthetics of derelict architecture. It discusses the tactile qualities that preserve aspects of an architectural idea in a way that tells the story of the life of the building. Patricia Morton puts it beautifully: The “afterlife” of buildings is critical evidence of the origins of the present in the “trash of history.”2 In another work, Rumiko Handa puts a different but insightful twist to it; she argues that “afterlife” is in fact the very life of a building, as the notion that architecture is complete when the construction is finished is problematic and unrealistic.3

Beyond the obvious, there is far more to architectural ruin in Greece than meets the eye. The majestic ‘left overs’ carry on more clout and reverence than most of the modern structures in the ancient city. I know not of a single modern edifice both on the Mainland or Islands of Greece that gets nearly as much attention. In fact, as it is to be seen in the Acropolis Museum—same as any museum for that matter—the fantastic ultra-modern building complex is valuable only in context of its content. The fascination with the ancient Greek ruins have a well-established history of its own. Julien-David le Roy’s Les Ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Grece, published in 1758, is a testament to this.

Originally the notable architectural ruin may have been accidental or an unplanned result that evolved through time in some cases such as the great ruins (Colosseum, Acropolis, Machu Picchu, etc.) or through a devastating event such as war (Racqua, Post WWII Warsaw, Paris, etc.), but as civilization passed, the idea of ruin flourish among romantics, artists, and culturists such that the purposeful creation and incorporation of the ideology of ruin into their art became the order of the day. This was particularly true of the 18th century when ruin was centre-stage in European art.4 Poets, novelists, landscapists, and architects were overcome with the idea of a picturesque rot. The craze, Dillon (2012) continues, inspired some well-known architectural absurdities: in 1740 Westmeath, Lord Belvedere built a ruined abbey to block the view of a house where his ex-wife had moved in with his brother, and in 1796 William Beckford designed his fantastical Fonhill Abbey as a “habitable ruin,” sadly the thing kept falling down. In the 20th century, Albert Speers, Hitler’s architect, is believed to have planned and designed Hitler’s future Germania with its potential “ruin value” in mind. Speers believed that using special materials, or by obeying certain laws of statics, one might be able to build structures, which, after hundreds or thousands of years, would more or less resemble our Roman models.5 The Second World War will however test the taste for ruin to its limits.6

Fig. 21: Delicate balance. Restoration work shows new marble integrated with the old on the Erechtheion.

Fig. 22: Part of the ruins of the Parthenon showing triglyph and the corner area of the pediment.

Fig. 23: A synthesis of the old and the new. Columns of the Parthenon showing the ‘marriage’ of old and new marble in a restoration effort.

Fig. 24: Details of the ornamentation on the Parthenon.

Fig. 25: Scaffolds around a Parthenon column show progress in restoration work.

Fig. 26: A fragment of old acroterium lay about on the Acropolis hill.

Short Note on the Acropolis Museum and the National Archaeological Museum of Athens

The Acropolis Museum is a notable building and a place of pride to Athenians and Greece as a whole. The beautiful edifice designed by architect Bernard Tschumi in conjunction with Greek Architect Michael Photiadis stands over the old ruins of a Roman and early Byzantine settlement in Athens. Tschumi’s Acropolis Museum was opened to the public in 2009 and it houses over 4,000 archaeological objects mostly from excavation projects on and around the Acropolis hill. This ultra-modern building is not the first museum for the Acropolis. An initial collection house dedicated to artifacts found on the acropolis was established as far back as 1874. This museum later grew in the 1950s but the structure eventually became inadequate as archaeological work on the Acropolis advanced discovering far more objects than the building could hold, thus the idea for a grand new building was conceived. The current Acropolis Museum allows you see the active ancient archaeological site just below it through a glass floor. The museum is located close to the hill just opposite the Theatre of Dionysus and it is about a 15-minute walk from the Parthenon itself. Inside the museum, one will find an impressive array of relics from the ancient glory of the Acropolis. Both fragments of the original and plaster reconstructions are displayed in a way that educates the viewer on the actual and original forms that adorned the gables of the great temples.

Fig. 27: An installation inside the Acropolis Museum. The piece shows the remnant of the architectural sculptures that once adorned the pediment of the old temple.

Fig. 28: The Women of Caryae—Caryatids in the Acropolis Museum.

Fig. 29: Frontal view of a caryatid with long robe (as Vitruvius puts it) in the Acropolis Museum.

Fig. 30: Details of the upper frontal side of a caryatid.

Fig. 31: Side view of a caryatid with long robe on display in the Acropolis Museum.

Fig. 32: Several friezes, steles, and architectural sculptures excavated from the Acropolis hill are on display inside the museum.

Fig. 33: Remnant of two marble torso pieces from a pediment sculpture.

Fig. 34: A 1990 plaster model reconstruction of the floral akroterion that once crowned the top of the Parthenon pediment. The original akroterion on top of the ancient Parthenon had a height of 4 meters.

Fig. 35: Plaster models of pediment sculptures from the Parthenon. See Figs. 3 and 4 where the original still adorns the ruins of the Parthenon.

Fig. 36: A cityscape view of the city of Athens just around the slope of the Acropolis hill. In the centre of the photo is the modern Acropolis Museum. In the foreground is the Theatre of Dionysus.

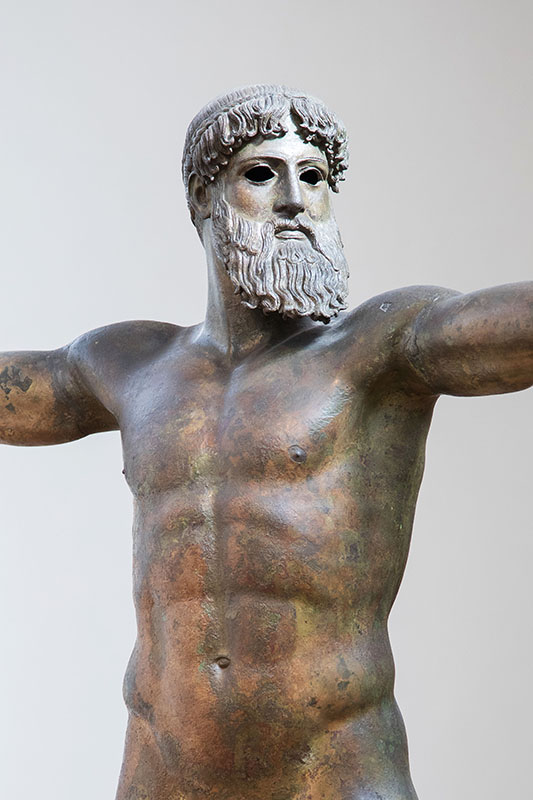

If one is bemused by the collection of the Acropolis Museum, then he has not visited the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Formerly called the Central Museum but renamed in 1881, the National Archaeological Museum boasts of over 11,000 pieces of valuable exhibits. The museum is said to be the largest in Greece and one of the most reputed on the world scene for its rich collection, which provides a detailed picture of ancient Greek civilization. The Neo-Classical building was designed by L. Lange for the Greek government and the construction, which started around 1865, was completed in 1889. The museum houses world renowned pieces like the bronze statue of Poseidon, known as the Artemision Bronze, the famous gold funeral mask of Agamemnon, which has been dated to 1550–1500 BC, several well preserved frescoes and wall art from antiquity, several friezes, and remnants of different architectural elements of great temples. From its metallurgy collection, it also boasts of the famous Antikythera mechanism. The museum’s 120-year-old library of archaeology is also a collection to marvel at. With over 20,000 volumes, it houses several rare volumes on art, science, ancient religion, and philosophy.

Fig. 37: View approaching the National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Fig. 38: Roof-mounted sculptures to the left of the approach view of the National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

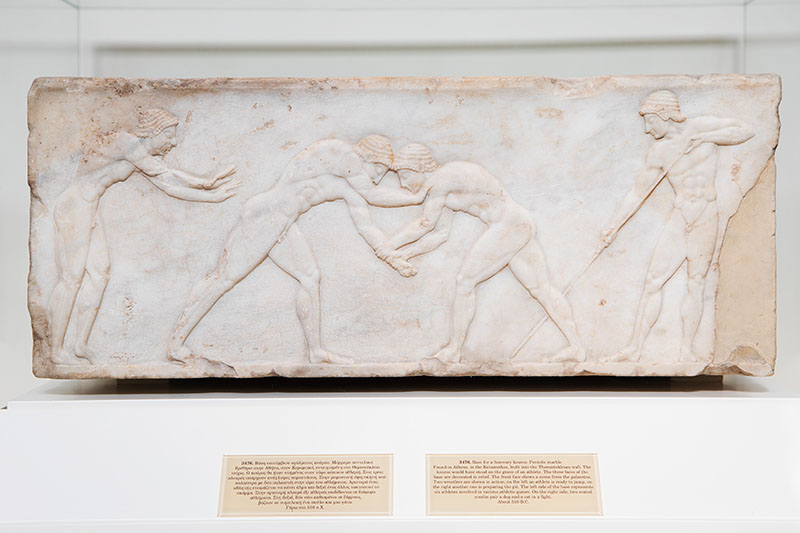

Fig. 39: The base of a funerary kouros made of Pentelic marble. The fine piece built into the Themistokleian wall was found in Kerameikos in Athens and it is date to around 510 BC.

Fig. 40: Fragments from the largest rotunda in ancient Greece—The Tholos. The Tholos was built between 365–355 BC. The lion heads acted as a water sprout, a type of gargoyle. Several heads lined the base of the rotunda’s roof.

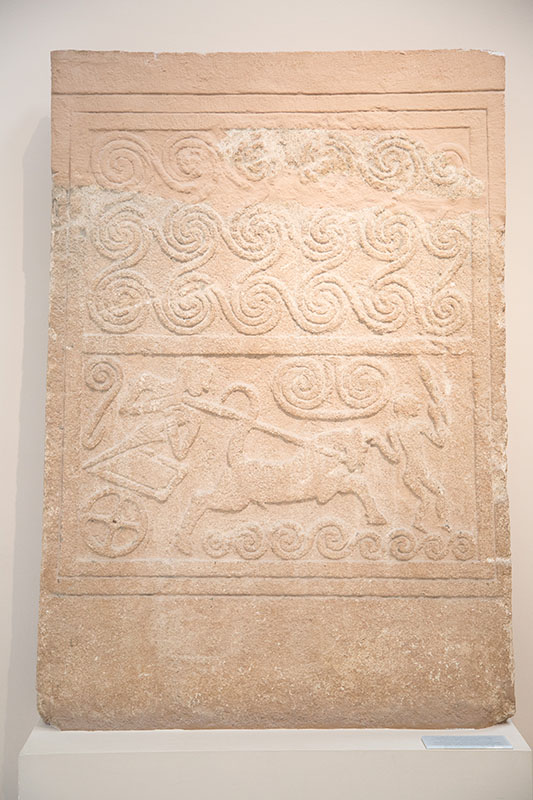

Fig. 41: Funerary stele made out of Poros stone features a chariot scene. This piece is a 16th-century work and was found at a Mycenaen grave.

Fig. 42: Another grave stele made of Pentelic marble and dated around the 4th century BC. This piece if from the north western part of Athens.

Fig. 43: The bronze statue of Poseidon also known as the Artemision Bronze. The slightly larger than life size naturalistic piece was recovered from the sea off Cape Artemision hence the name.

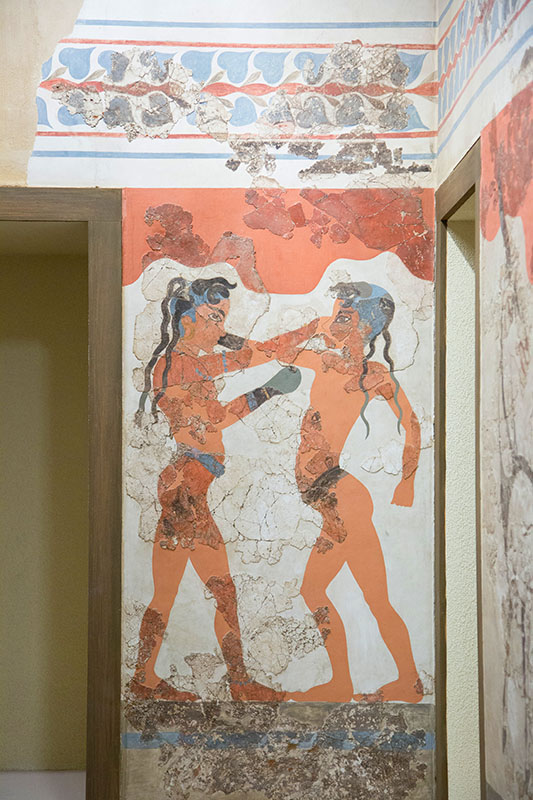

Fig. 44: A beautiful and well preserved fresco from the island of Thera. This room features delicate paintings on plastered walls. The ‘Boxing Children’ and the antelope frescoes are now both celebrated works in their own rights.

Fig. 45: Detail of the ‘Boxing Children’ fresco.

Fig. 46: Another fine example of well-preserved wall fresco found in Akrotiri. The fresco features a colorful landscape in spring. Researchers believe that the art depicts the rocky landscape of Theran before the volcanic eruption.

Fig. 47: Detail of the landscape in spring fresco from Akrotiri.

Ruins are obviously more than just the reminders of an illustrious past, they are also stencils for future. Ruins speak to persistence and a quality that becomes imperative if the future is to see a trace of the present. These critical thoughts about ruins are instructive to me even as I battle with the cultural conflict inside me about the value of ruins. In all, I find some sense and direction in the words of Georg Simmel from his essay “The Ruin” as quoted by Brian Dillon in his article "Fragments from the History of Ruin": "Architecture is the only art in which the great struggle between the will of the spirit and the necessity of nature issues into real peace, in which the soul in its upward striving and nature in its gravity are held in balance. Nature begins to have the upper hand: the brute, downwards-dragging, corroding, crumbing power produces a new form. But at what point can nature be said to be victorious in this battle between formal spirit and organic substance? The ruin is not the triumph of nature, but an intermediate moment, a fragile equilibrium between persistence and decay."7

Fig. 48: A view of the city of Athens in the lowlands around the Lycabettus hill.

Fig. 49: Athens city centre in the lowlands around the Acropolis hill.

Fig. 50: A night view of the Parthenon on the Acropolis hill.

1 Marwa Al-Sabouni, The Battle For Home: The Vision of a Young Architect in Syria (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2016), 8.

2 Patricia Morton, "The Afterlife of Buildings: Architecture and Walter Benjamin's Theory of History" in Rethinking Architectural Historiography, ed. Dana Arnold, Elvan Altan Ergut, and Belgin Turan Ozkaya (Routledge, 2006), 360.

3 Rumiko Handa, “Learning from the Ruins: Theorizing the Performance of the Incomplete, Imperfect, and Impermanent” (paper delivered at Architecture, Culture, and Spirituality Symposium, 2012).

4 Brian Dillon, “Ruin lust: Our love affair with decaying buildings,” The Guardian, February 17, 2012, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2012/feb/17/ruins-love-affair-decayed-buildings (accessed January 11, 2018).

5 Brian Dillon, “Fragments from a History of Ruins,” Cabinet, Issue 20 Ruins, Winter 2005/06.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top