-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Morocco: Reflections on Remembering Andalusia and the Absence of Ottomans

After my journey through southern Spain, this month finds me on the other side of the Straits of Gibraltar, in Morocco. Despite the fact that I am on a different continent, in a different country and surrounded by a different culture, the medieval and early modern Islamic architecture encountered here are every step evokes the monuments of Andalusia. Therefore, I will include some additional images from Spain that did not find their place in last month’s blog.

Figure 1: Minaret of the Kutubiyya Mosque, Marrakesh (P. Blessing)

Figure 2: Ruins of the first Kutubiyya Mosque, Marrakesh (P. Blessing)

In Marrakesh, on the outskirts of the medina, the old city, one cannot miss the minaret of the Kutubiyya Mosque (Figure 1), towering over the low roofs of the prayer hall visible on the left. As with all mosques in Morocco, access to the Kutubiyya is restricted to Muslims. Strictly enforced, this prohibition has its roots in the colonial period; it was instituted by resident general (head of the French colonial administration) Hubert Lyautey, in 1912, and maintained after Morocco’s independence in 1956. Hence, no chance to view the mosque space inside, except for the rare glimpse through an open door. Returning to the Kutubiyya, an importance aspect of this building is that it was built twice within the space of a few years. Following the conquest of Marrakech in 1147, inflicting a final defeat on the Almoravid dynasty, Almohad sultan Abd al-Mu’min commissioned the construction of the first Kutubiyya (Figure 2). Construction of the first mosque began between 1147 and 1154, and was completed by 1157; the second mosque was probably built between 1154 and 1162, although sources vary on this. Motives for the construction of two adjoining mosques within a few years are unclear; clear is, however, that both buildings remained in use jointly, and that the first mosque only arrived in its ruined state long after. The minbar of the Kutubiyya, now preserved in the ruined sixteenth-century Badi Palace in Marrakesh, was produced in Cordoba in 1137 for the Almoravid sultan, who had it destined for the mosque he founded in his capital. That building was destroyed by the Almohads, but the minbar (pulpit used during Friday prayers) remained in use in the Kutubiyya until 1962; it was carefully restored in the 1990s. This object, produced in Andalusia for a site in Morocco in the twelfth century is a direct testimony to the fact that these regions were closely connected in the Middle Ages.

Figure 3: Detail of top, minaret of the Kutubiyya Mosque, Marrakesh (P. Blessing)

Figure 4: Giralda, formerly minaret of the Great Mosque of Seville, Spain (P. Blessing)

Figure 5: Tower of Hasan, Rabat (P. Blessing)

The minaret of the Kutubiyya, built at the end of construction of the first mosque (hence, roughly around 1154–55) is monumental to the same extent as the Giralda, the minaret of the Great Mosque of Seville, built by Almohad patrons in 1184. The top of the Kutubiyya minaret (Figure 3) allows in fact for a reconstruction of the original state of the Giralda (Figure 4) that now finishes as a bell tower, added in the sixteenth century. The largest of Almohad minarets, that of the so-called Hasan Mosque (Figure 5) in Rabat, begun under the auspices of Ya’qub al-Mansur in 1195, was never finished: construction was abandoned at the sultan’s death in 1199. Standing at 44m in its incomplete state, it was likely to have been planned at twice that height. Currently, the minaret is being restored, and hence I was not able to take detailed photographs of its decoration. Neither of these minarets is accessible, so I am not able to offer the overall views that I had for the remains of the Seville mosque.

Figure 6: Qayrawiyin Mosque, Fes, minaret and room seen at center of city view (P. Blessing)

Figure 7: Qayrawiyin Mosque, Fes, view through portal on Talaa Kabira (P. Blessing)

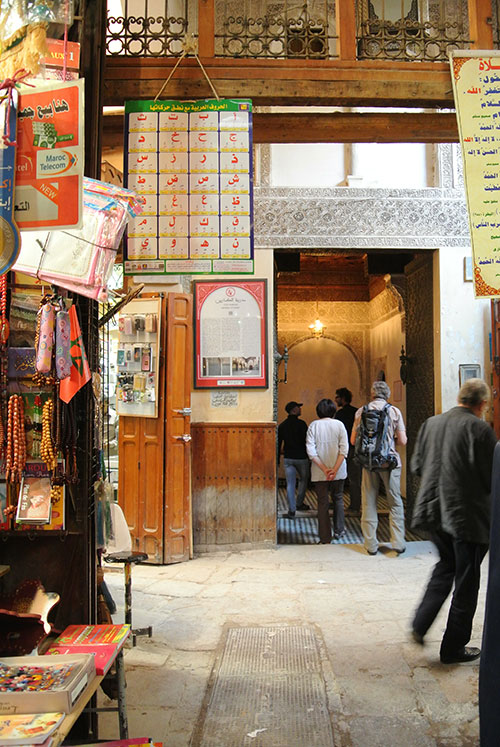

Of the few glimpses of mosques that I can offer, one is of the Qayrawiyin Mosque in Fes (Figures 6 and 7). One of the oldest mosques in Fes, it was founded in 859 and expanded multiple times, particularly under Almoravid rule in the twelfth century; the current form goes back to the fourteenth century. The mosque is located in the middle of the medina of Fes, a living space that is very much inhabited by the local population, full of stores and artisans’ workshops, rather than a tourist site (Figure 8).

Figure 8: View of Talaa Kabira street in the medina of Fes, with Bou Inaniya Clock at left (P. Blessing)

Figure 9: Bu Inaniya Madrasa, view of courtyard (P. Blessing)

Figure 10: Bu Inaniya Madrasa, view of prayer hall (P. Blessing)

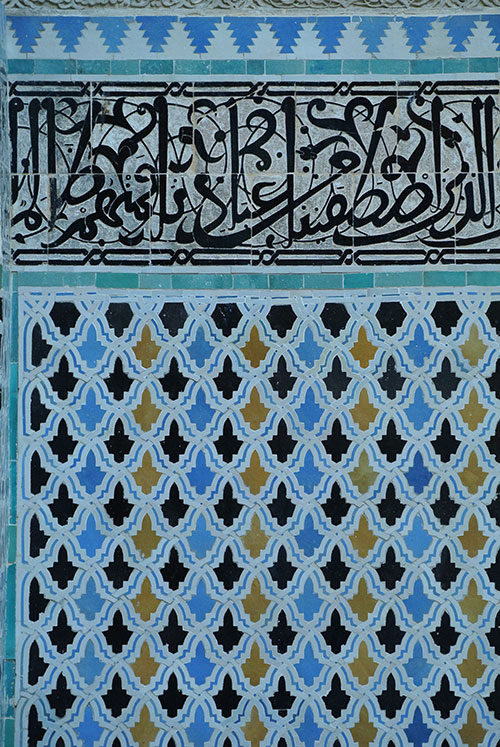

This same street view also show what remains of the fourteenth-century water clock that belonged to the Bu Inaniya Madrasa, founded by Merinid sultan Faris ibn Ali Abu Inan al-Mutawakkil in 1350. While the clock no longer functions, the madrasa is still in use, even though it can be visited. Entering into the monument, one is faced with a large courtyard, paved with marble (Figure 9). At the far end, and arcade divides the mosque space from the madrasa; access is restricted to Muslims, yet the open arches allow for a view into this small prayer hall (Figure 10). The decoration of the courtyard is one that is repeated in contemporary and later monuments in Morocco: tiled dadoes, stucco decoration with inscriptions and floral motifs, and carved wood under the eaves (Figures 11, 12, 13).

Figure 11: Bu Inaniya Madrasa, tiled dado (P. Blessing)

Figure 12: Bu Inaniya Madrasa, detail of stucco decoration with founder’s name (P. Blessing)

Figure 13: Bu Inaniya Madrasa, detail of carved wood under the eaves (P. Blessing)

At the center of the courtyard, the reflection of the building is caught in a pool (Figure 14); this recalls the intricate visual effects that I observed in the Alhambra last month. Since the madrasa also serves as a mosque, it has a minaret—visible from the courtyard, but not from the covered street outside (Figure 15). It is useful to remember here that this madrasa, along with the Madrasa al-Attarin that I will discuss next, is a close contemporary to the Nasrid palace complex in the Alhambra. The difference is in context: the abundance of decoration and different materials used for the sultan’s residence in Granada is here transposed into a religious monument. The only base for comparison to a religious monument in Nasrid Spain is the remaining prayer room of the Madrasa in Granada, where stucco decoration abounds but the tiles and wood used in exterior courtyard facades do not exists. This observation makes me think about the fluid nature of an architectural decoration that can serve multiple purposes; of inscription panels that can bear poetry just as well as Qur’an passages.

Figure 14: Bu Inaniya Madrasa, reflection of courtyard façade in pool (P. Blessing)

Figure 15: Bu Inaniya Madrasa, minaret, seen from courtyard (P. Blessing)

Built slightly earlier, in 1323–25, the smaller Madrasa al-Attarin has a narrow courtyard that is difficult to capture in an overall view (Figure 16). The decorative scheme closely resembles the one in the Bu Inaniya Madrasa: from bottom to top—tiles, stucco, carved wood. The variations lies in the details, in the motifs used for the tiles, especially (Figure 17). In the small prayer room, a bronze chandelier (Figure 18) offers an example of fourteenth-century metalwork, even though it now comes with electrical wires and light bulbs. The entrance (Figure 19) of the madrasa is located that the end of the Talaa Kabira, one of the main streets of the medina; like the other madrasas in Fes, this monument does not strike with a monumental portal, but rather with the splendor of its courtyard.

Figure 16: Madrasa al-Attarin, view of courtyard (P. Blessing)

Figure 17: Madrasa al-Attarin, detail of tile decoration (P. Blessing)

Figure 18: Madrasa al-Attarin, chandelier (P. Blessing)

Figure 19: Madrasa al-Attarin, entrance (P. Blessing)

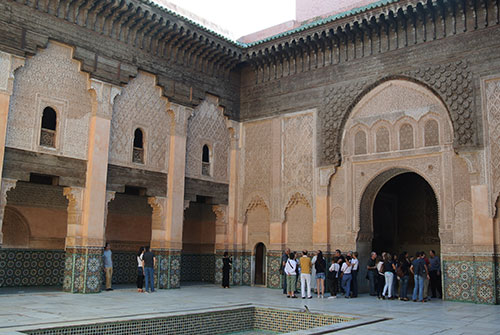

This decorative vocabulary neither stopped in the fourteenth century, nor with the end of Merinid rule. It continued to be used into the eighteenth century, and even the nineteenth-century mansions that now often serve as hotels still have recourse to rich tile and stucco decoration. One of the most pertinent examples, since it is also a madrasa like the two monuments just discussed, is the Ben Youssef (Ibn Yusuf) Madrasa in Marrakesh (Figures 20 and 21). Even though it carries the name of a fifteenth-century Merinid governor, the current monument was built for Saadian sultan Sidi Abdallah al-Ghalib in the mid-sixteenth century. Striking at first sight is its monumental scale, much larger than the Madrasa al-Attarin and the Bu Inaniya.

Figure 20: Ben Youssef Madrasa, entrance (P. Blessing)

Figure 21: Ben Youssef Madrasa, view of courtyard (P. Blessing)

Considering the date of this structure, and the fact that its decoration is so closely continuing that of monuments built two hundred years earlier, I all of a sudden came to a realization. This was the first time in my travels in the Arab world that I was in a region never conquered by the Ottomans. With the conquest of Greater Syria and Egypt in the winter of 1516–17, these regions were integrated into the Ottoman Empire. Even though local architectural and artistic cultures remained strong, everything was progressively covered, to various degrees, with a layer of Ottoman visual culture. The pencil minarets and large round domes immediately click “Ottoman.” Even when a local technique like ablaq, the striped black-and-white stone technique typical of Ayyubid and Mamluk architecture in Syria, continues to be used, monuments like theDarwishiya Mosque in Damascus, built in 1574 (Figure 22) betray their Ottoman pedigree.

Figure 22: Darwishiya Mosque, Damascus, Syria, in a photograph taken in 2005 (P. Blessing)

I could have used many more examples of Ottoman monuments in the Syria or Egypt, yet this one will stand in here for the ways in which the Ottoman conquest transformed architecture. In Morocco, however, we are faced with—in the words of my friend and colleague Heather Ferguson—non-Ottomanized space. This is a new direction of thinking that I will need to pursue. This is exactly the type of insight emerging from travel in places beyond one’s research focus that the Brooks Fellowship makes possible.

Returning to the Ben Youssef Madrasa, the details of the decoration enchant once more with the combination of tile, stucco, and woodcarving. The mosque, located in the axis of the monument, is here a relatively large space. The mihrab, deeply recessed, is covered with a muqarnas dome; the stucco retains some of its original polychromy (Figure 23).

Figure 23: Ben Youssef Madrasa, dome over mihrab (P. Blessing)

Several other monuments also show the continued use of the type of decoration developed in Nasrid Andalusia and Merinid Morocco. Since I have not had the opportunity to write about funerary architecture in my post on Andalusia (where no such monuments remain), let me now turn to two examples. The first is the so-called Saadian Tombs (Figure 24) in Marrakech, the burials of several rulers of dynasty of the Saadians in the second half of the sixteenth century. Hidden behind a large mosque, this funerary garden was closed up in the eighteenth century and, according to local and guidebook lore, not rediscovered until 1917. Numerous burials are placed under slabs decorated with tile mosaic devoid of inscriptions, while others have marble steles embedded in them (Figure 25). Several mausolea—in shape reminiscent of the fourteenth-century pavilions of the Court of the Lions at the Alhambra—are also part of the site (Figures 26 and 27).

Figure 24: Saadian Tombs, Marrakesh, entrance (P. Blessing)

Figure 25: Saadian Tombs, Marrakesh, tomb slabs (P. Blessing)

Figure 26: Saadian Tombs, Marrakesh, view of small mausoleum (P. Blessing)

Figure 27: Saadian Tombs, Marrakesh, interior of large mausoleum (P. Blessing)

A very different view presents itself at the fortified necropolis of Chellah, just outside the walls of Marrakesh (Figure 28). Here, the ruined burials of several Merinid rulers are placed next to a Roman site, dotted with marabouts, the tombs of saints (Figure 29). The Merinid remains consist of the ruins of a mosque, madrasa, bathhouse, and mausoleum, all built in close proximity to each other. On a decidedly un-architectural note, the site is home to a large colony of sedentary storks who have built theirs nests on the minaret (Figure 30) and atop the ruins of the madrasa (Figure 31). I will leave the reader with these images, given the abundance of other sites that could be discussed, and the little space that remains.

Figure 28: Necropolis of Chellah, Rabat, portal (P. Blessing)

Figure 29: Necropolis of Chellah, Rabat, view: Roman ruins in foreground, Merinid mosque at far left, marabout at far right (P. Blessing)

Figure 30: Necropolis of Chellah, Rabat, Merinid Minaret (P. Blessing)

Figure 31: Necropolis of Chellah, Rabat, courtyard of madrasa (P. Blessing)

Recommended Readings

Alaoui, Amina El Alami. Ombres sur l’amandier (Rabat: Casa Express, 2013).

Andalusian Morocco: A Discovery in Living Art, Museum with no Frontiers Series (Rabat: Ministry of Cultural Affairs of the Kingdom of Morocco and Vienna: INGO Museum with no Frontiers, 2002).

Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. Egypt's Adjustment to Ottoman Rule: Institutions, Waqf and Architecture in Cairo, 16th and 17th Centuries (Leiden and New York: Brill, 1994)

Bloom, Jonathan M., Ahmed Toufiq et al. The Minbar from the Kutubiyya (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998), out of print, pdf available at: http://www.metmuseum.org/research/metpublications/The_Minbar_from_the_Kutubiyya_Mosque# (accessed 18 November 2015)

Ghouirgate, Mehdi. L’ordre almohade (1120-1269): Une nouvelle lecture anthropologique (Toulouse: Presses universitaires du Mirail, 2014).

Lintz, Yannick, Claire Déléry and Bulle Tuil Leonetti, eds., Le Maroc médiéval: Un empire de l’Afrique à l’Espagne, exhibition catalog, Paris: Musée du Louvre and Hazan, 2014.

Rivet, Daniel. Histoire du Maroc (Paris: Fayard, 2012).

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top