-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Connectivity and ‘Green’ Craft: Exploring the Infrastructure and Architecture of the Faroe Islands

Danielle S. Willkens is the 2015 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs and videos are by the author, unless otherwise noted.

On one particularly foggy morning, my explorations through the Faroe Islands started with an unexpected scene. I was staying in Hoyvík, a suburb of the capital of Tórshavn on Streymoy, and as I traveled down the winding road from my rented room, I watched a series of red-faced pre-teens run up the hill. Their teachers, bundled together in a car and assisted by warm cups of coffee, were sitting at the base of the hill, marking the students’ arms with a Sharpie as they passed to record the completion of another lap around the neighborhood school. I later came to understand that these students were participating in a weekly physical education outing, one that occurred in all forms of weather, and in the capital it was not uncommon to spot a student wandering the streets still proudly marked with their temporary tattoo. After a few weeks in the Faroes, it became clear that the nation’s inhabitants were well adapted to the Jeykell and Hyde weather of the islands, changing from bright blue skies to hail over the course of minutes (Figures 1 and 2). Despite the unpredictable weather, the outdoor occupations of fishing and farming are still the dominant professions but tourism is on the rise, growing by approximately 10% each year. It looks as though 2016 will mark a banner year: the number of annual tourists is expected to exceed the regular Faroese population of nearly 50,000.

Figure 1. Blue skies and a turquoise sea near the town of Fámjin on Suðuroy. This image was captured just a half an hour before Figure 2.

Figure 2. Thirty kilometers south of Fámjin, dense fog nearly conceals the Akraberg lighthouse on the southernmost point of the Faroe Islands, located in Sumba on Suðuroy. Such weather automatically triggers the foghorn at the now-unmanned lighthouse, sounding at 60-second intervals to warn fisherman as well as freight and commercial liners of the dangers of the obscured, rocky shore.

The Ministry of Trade and Industry have been actively campaigning for increased tourist numbers and petitioned for an independent, self-supporting agency to encourage the exploration of the Faroe Islands and Faroese culture, launching the Visit Faroe Islands Tourist Board in 2001. As evidenced by the growing number of tourists, the campaign is working and it has been bolstered by the increasing numbers of cruise ships docking at the capital city Tórshavn, the increased frequency of flights to the only commercial airport on the island of Vágar, and the cultivation of an efficient inter-island transportation network, consisting of highly maintained roads and public access to governmentally-subsidized buses and ferries (Figure 3). Nonetheless, when I shared my plans to visit the Faroe Islands, many people seemed to find it an odd choice. Although captivating for its natural sites, it appeared to be an isolated location with, perhaps, little of architectural interest (Figure 4). This, thankfully, was not the case: the islands offered an interesting glimpse into sustainable infrastructure, a built heritage that adeptly responds to the limitations of local materials and harsh realities of the North Atlantic climate, and creative approaches to industry and entrepreneurialism amid dramatic landscapes.

Figure 3. An aerial view of twilight in the capital city of Tórshvan, Stremoy.

Figure 4. An abandoned farm building in Suðuroy that represents an atypical construction for the agricultural buildings of the Faroe since it mixes the building materials of dry-laid stone, concrete with rubble for aggregate, and wood.

Navigating the Faroe Islands

Located near the centroid of a geographical triangle connecting Iceland, Norway, and the Scottish Islands, the Faroe Islands consist of eighteen islands, seventeen of which are inhabited. The islands are the eroded remnants of the Thulean plateau, characterized by deep, glacial fjords, steep mountains, and some of the largest promontories in the world, such as Enniberg in Viðareiði, Viðoy (Figures 5–7).1

Figure 5. A panoramic image of small agricultural operations near Gjógv, Esturoy, captured while traveling on the Smyril Line ferry the Norrøna from Tórshavn to Seyðisfjörður, Iceland. Launched in 1983, the ferry also serves Hirtshals in the north of Denmark. More like a small cruise ship than a ferry, the vessel can carry 1400 passengers and 450 cars.

Figure 6. An aerial view of one of the deep valleys of the Faroes, located in Elduvík, Esyturoy.

Figure 7. One of the jagged, eroded islands rising from the sea near Bøur, Vágar.

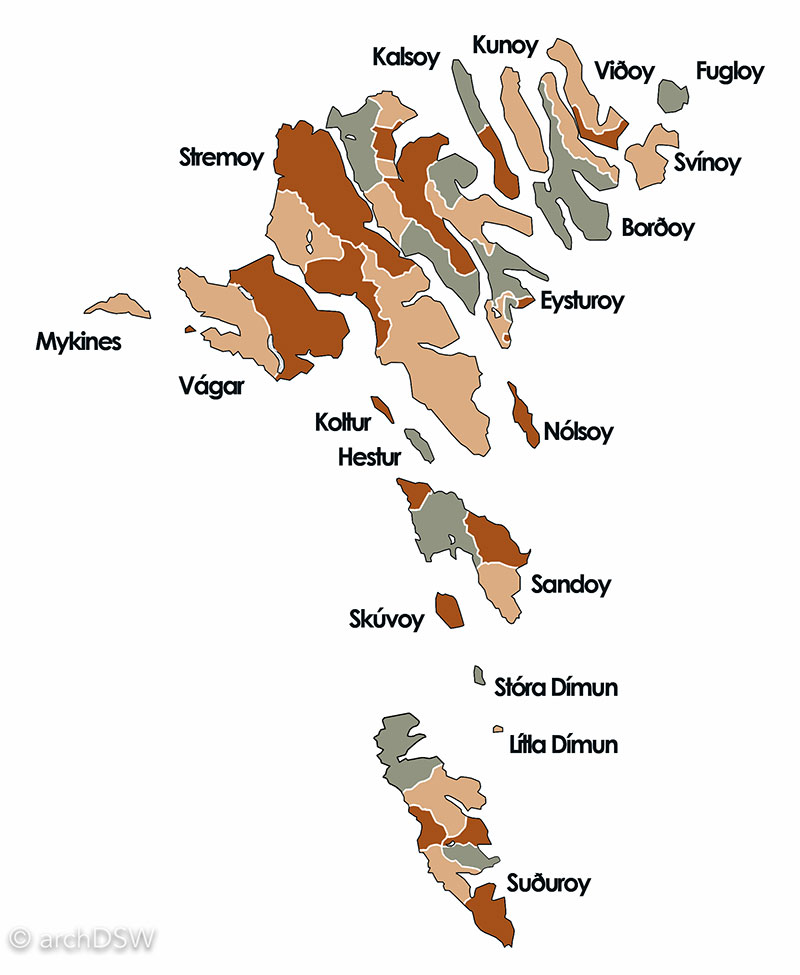

Overall, the islands are organized into a series of groups (Maps 1 and 2):

- the northern islands of Borðoy, Fugloy, Kalsoy, Kunoy, Svinoy, Viðoy;

- the ‘easterly’ island of Esturoy;

- the largest and most populous island of Streymoy and its small neighbors of Nólsoy, Hester, Koltur;

- the western islands of Vágar, home to the airport, and the sparsely populated puffin island of Mykines;

- the southern islands of Sandoy, Skuyvoy, Stóra Dímun, and Lítla Dímun;

- and the geologically distinctive, southernmost island of Suðuroy.

Map 1. The identified island groupings in the Faroes show a relatively even distribution of land.

Map 2. Beyond the clustered classifications of the islands, each of the islands are subdivided into regional districts, largely determined by geographical features such as peaks, swales, and lakes.

Although a similar climate to Iceland, the Faroe Islands are more susceptible to the impacts of North Atlantic storms and I can certainly attest to the rough seas that cancelled two attempts to visit the westernmost isle of Mykines and made for rocky ferry rides in the southern islands. Nonetheless, the islands are actively positioning themselves as a tourist destination with a new series of ‘Visit Faroe Islands’ campaigns that advertise the islands as the ‘best kept secret in Europe.’ Leveraging legends, music, turf-covered architecture, and woolen crafts in partnership with a unique geology, the Faroes are promoting themselves as a destination that marries distinctive cultural traditions with an astounding landscape (Figure 8). In 2007, National Geographic Traveler named the Faroes the best islands in the world following a survey of 111 island destinations by 522 sustainable tourism experts. The Faroes made National Geographic Traveler headlines again when they were named the winners of the readers’ choice for the best destinations in 2015, reinforcing the characteristics extolled by the Visit Faroe Islands campaign: ‘unspoiled, unexplored, unbelievable.’ During my stay in late August and early September, these seemed to be apt descriptors: the landscapes of the islands are entirely memorizing and it was not uncommon to spend the better part of a day, especially in the north, exploring with only seabirds, sheep, and the occasional whale as companions. Each town was welcoming and this post will explore how each of the villages along the peninsulas and narrow fjords consist of a predictable kit of parts. Only the largest urban centers of Tórshavn and Klaksvík, and the medieval town of Kirkjubøur, truly veered from this Faroese formula for communities.

Figure 8. An aerial view of the turf-covered homes of Elduvík, Esyturoy.

Throughout my travels I was continually intrigued by the juxtapositions of tradition and modernity. For example, despite the impressive national infrastructure that connects 85% of the Faroe Islands by roadway, about 15% of the nation relies on ferry service and there are still a few sites that are quite remote, including the three smallest islands that are accessible only by boat or helicopter, and only in the best weather conditions. (Figure 9).2

Figure 9. Fish drying on the stern of a trawler in the harbor of Skopun on Sandoy that connects the island with its neighbors, Hestur and Streymoy.

The islands are, pleasantly, not tainted with foreign chains or restaurants, but this also means that one has to carefully plan journeys and meals since it is entirely possible to find yourself on an island without a single shop or convenience store; even Tórshavn and Klaksvík become ghost towns on Sundays when the vast majority of businesses close and governmentally-sponsored public transportation systems cease regular operations. Portions of the islands, particularly the north, are sparsely populated but steady, 4G-network service is available throughout the Faroes to the extent that even areas of the North Atlantic provide a steady signal for fisherman and ferry-goers (Video 1). Additionally, projects such as ‘Sheepview360’, a grassroots initiative in partnership with Google to digitally document the islands using the quadrupeds that outnumber Faroese inhabitants two-to-one, successfully pairs traditional husbandry with technology.

Video 1. Despite the remote location and lack of a natural harbor, the town of Trøllanes on Kalsoy has a strong network signal that keeps the agricultural community connected.

As briefly mentioned in the August blog post and illustrated in this map produced by the Visit Faroe Islands Tourist Board, the nearly 2,000 square kilometers of the eighteen Faroe Islands are connected through an impressive, nationalized system of ferries, bridges, and tunnels through layer-cake mountains of basalt with coal cores. In the 1980s, the government sponsored a series of new roads and tunnels, bolstering the interconnectivity of the islands and this dedication to transportation infrastructure has not waned. During my visit, I saw three tunnels under construction: one replacing a small midcentury construction and two entirely new routes, one on Viðoy to replace a cliffside road prove to landslides and a large, subterranean tunnel that will connect the islands of Streymoy and Sandoy. Additional subterranean tunnels are in the planning phases: two to connect the southern islands and one to relieve traffic congestion between the two most populous islands of Streymoy and Esturoy, proving that twenty-first century infrastructure projects are key proprieties for the Faroese government. This, however, may also be an indication of the islands’ desire to increase tourism while providing an essential financial structure to support the maintenance of national transportation infrastructure: the two extant subterranean tunnels Vágatunnilin (2002), connecting the airport at Vágar with the capital island of Streymoy, and Norðoyatunnilin (2006), connecting the second most populous isle of Eystuory with the both have associated tolls. In addition to the governmentally-sponsored videos that instruct visitors about the perils of driving in the Faroes, such as the proliferation car-challenging sheep and one lane tunnels, the tourist board has imposed a travel-friendly system for navigating the national infrastructure considering that the rental cars on the islands are equipped with digital chips that register trips through the tunnels and automatically charge renters the 100 DKK fee for a round trip journey (Videos 2 and 3). This system is particularly effective due to the highly ordered structure for points of arrival and departure for visitors to the Faroe Islands.

Video 2. Scenes from the Faroe Islands, exploring the island of Eysturoy.

Video 3. Scenes from the Faroe Islands, taking the ferry from Klaksvík to Syðradalur to explore the island of Kalsoy. The drive passed through the following towns: Húsar, Mikladalur, and Trøllanes.

Unlike the array of airlines that operate through Iceland, only three companies manage transport by land and sea to the Faroes Islands, meaning that the nation does not function as a popular layover destination. Although the Royal Trade Monopoly was disbanded in 1856 and the Act on Faroese Home Rule passed on March 23, 1948, recognizing the Faroe Islands as a ‘self-governing community within the Kingdom of Denmark’, much of the Faroes still operates with a monopoly mentality. For example, until the introduction of Iceland Air flights in 2014, the sole airport for the Faroe Islands served only Atlantic Airways, a national, commercial airline founded in 1988. Similarly, only the Smyril Line ferry (the Norrøna) provides service to Iceland and Denmark. As the leading tour coordinator, hotel liaison, and rental car company, the relatively new and rapidly growing 62°N operates a tourism monopoly in the Faroes. Finally, in terms of consumer consumption, Føroya Bjór has bottled the islands’ regulated supply of beer and soft drinks since 1888.

The Community Kit-of-Parts in the Faroe Islands

The Saga of the Faroe Islanders, recorded in the c.1380 manuscript Flateyjarbók, describes the Viking era from 980 to 1040 and relays the struggles of early settlers in their quest for arable land on the acidic and mineral-poor islands. Wildlife, however, was plentiful: when traveling in the 9th century, the Irish monk Dicuil nicknamed the area the ‘sheep islands’ and ‘paradise of birds.’3 These designations are still true: sheep are celebrated in the governmental seal, on postage stamps, and in the branding of a number of nationalized companies while much of the tourist economy, currently rated at 50,000 visitors a year, revolves around the unparalleled bird watching available throughout the archipelago: the puffin sanctuary on Mykines with only ten regular inhabitants, the famous bird cliffs of Vestmanna on Stremoy, the ‘bird islands’ of Fugloy in the north, and the opportunity to spot some of the more four million birds from over 150 species that are found throughout the islands.

The Faroes operated, largely, as a substance farming economy from the Viking age to the mid-1800s when attentions shifted to fishing.4 With little attention to commercial endeavors and access to a limited material palette, most of the buildings in the Faroe Islands are utilitarian. This does not imply, however, that the buildings are constructed without embellishments or thoughtful detailing (Figures 10 and 11).

Figure 10. The bright white doors and trim of this residence in Sandur on Sandoy strongly contrast with the tar-covered cladding. As evidenced by the location of the chimney, the roykstova is the heart of the home.

Figure 11. As an atypical structure, constructed entirely of stone, this residence sits in Sandur, adjacent to one of the many small lakes on Sandoy.

Unlike Iceland where corrugated iron, aluminum, and roughcast are the dominant materials, the vast majority of structures in the Faroe Islands are made of either wood, imported from Denmark or Norway, or board formed concrete. Fieldstones, largely basalt, were used for foundations and on of the most intriguing aspects of traditional Faroese architecture is the use of birch bark that acts as proto-flashing, protecting the stone structure or the end grain of the wooden cladding from water spilling from the deep profile, turf-covered roof (Figure 12).

Figure 12. A view of the birch ‘flashing’ in a traditional house in Tórshavn, Streymoy.

Tar was used as weatherproofing so the Faroese towns in the 19th century would have presented a largely uniform series of dwellings. Occasionally, brightly colored paint was used to distinguish the doors, framing elements, and sills of individual homes (Figure 13). The introduction of corrugated iron for weatherboard, however, altered the Faroese built landscape and offered homeowners the opportunity to select almost any color for their residence. This evolution in residential architecture makes it relatively easy to distinguish older towns from those of the 20th century: as a communal mandate, many of the historic towns retain black or red cladding in contrast to the rainbow palettes of newer villages (Figure 14).

Figure 13. A typical home in the Tinganes region of Tórshavn, Streymoy.

Figure 14. The brightly colored homes of Gjógv on Eysturoy provide an interesting contrast to the frequent grey skies of the Faroe Islands.

Many of the popular images of the Faroe Islands present a very provincial nation, filled with crumbling sheep sheds, picturesque boathouses, and long grasses growing wildly on simple, gabled homes and churches (Figure 15). Although this is a relatively accurate picture of the vernacular landscape, it is critical to note that there are carefully constructed regulations for land use and the organization of villages. From the medieval period, the precious arable land of the Faroes has been designated as bøur, the ‘infield’ heart of village that is divided into plats for crops, hay, and winter grazing. Everyone in the village has access to a portion of the bøur as well as a portion of hagi, the designed ‘outfield’ of uncultivated land used for summer grazing. Land laws also provided that each villager had access to a cliffside for bird hunting and, where accessible, communal boats slips in the harbor (Video 4).

Figure 15. The remnants of dry laid stone fishing huts line the largest lake in the Faroe Islands, located near Sørvágur on Vágar.

Video 4. Drone footage of the Sandvík on Suðuroy, Faroe Islands, featuring a microcosm of Faroese built and natural forms: plot lines subdiving arable land, small wave breaks and boathouses, a mining enterprise, and striking birdcliffs.

The Faroese government continues its support of communal infrastructure. Even in the smallest of towns, consisting of less than ten inhabitants, there are streetlights, access to public transportation, and partially mechanized harbors for fishing (Figure 16). Although few towns have gas stations, convenience stores, or some form of a café, almost every town has a small public restroom with a generous, heated space complete with long benches for hikers, campers, and travelers to escape the unpredictable weather and comfortably wait for the local bus or ferry. Traditionally, villages had a parish church and cemetery; and the modern kit-of-parts for a typical Faroese village now also includes a football pitch and local landmark, as evidenced by the layout of towns such as Nólsoy (Figures 17-19) and Skálavík on Sandoy (Video 5).

Figure 16. A view of the bus stop and postal box, and in the distance the harbor, of the small town of Gjógv on Eysturoy.

Figure 17. Translated as ‘the narrow island, Nólsoy is a short ferry ride from Tórshavn and features a mixture of traditional turf-covered houses and colorful metal-clad residence. An archway made from the jawbone of a sperm whale marks the harbor’s entry.

Figure 18. Unlike more modern churches, the cemetery of Nólsoy is adjacent to the church (1863).

Figure 19. Presenting an aerial view of Faroese contrasts, the well-groomed football pitch of Nólsoy sits below the a series of deteriorating stone structures that once comprised the heart of the town.

Video 5. Drone footage of the Skálavík, Sandoy on the Faroe Islands, featuring the harbor and a stone church from 1891.

As illustrated in the preceding photographs of Nólsoy and the aerial footage of Skálavík, parish churches can be found in almost every Faroese village. The 18th and early 19th century structures are typically made of stone, sometimes with wooden cladding for increased insulation, and have turf roofs (Figure 19–23). In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the craftsmen of each community used the local church as an opportunity to showcase their well-practiced skills in woodworking, developed through boat building and residential construction, and the delicacy of their metalworking. Each church has a distinctive color palette, an embellished screen or series of unique apertures, and an iron weathervane proclaiming the year of consecration. Select churches have preserved hardware, such as the door handles of Húsar’s church (1919) on Kalsoy that feature pilot whales (Figures 24a and 24b).

Figure 20. The church in Sandur on Sandoy was constructed in 1839 but it is the sixth church on the site. Located near one of the more fertile areas of the Faroes, Sandur has been a site of worship since 1000 and archaeological excavations have uncovered the remains of eleven early Christian burials.

Figure 21. The church of Hvalvíksvegur on Streymoy dates to 1837 and closely resembles the Sandur church.

Figure 22. The church in Húsavík on Sandoy dates to the 1840s.

Figure 23. Built in 1891, the church in Skálavík on Sandoy has the atypical addition of a transept.

Figures 24a and 24b. The church at Húsar on Kalsoy celebrates the grinds of the Faroe Islands, a communal pilot whale hunt described in more detail in the later portion of this blog post.

Many churches also serve as local memorials, featuring scaled models of wooden fishing boats and ships that were lost at sea, such as the model of the Danish East India Company’s Norke Løve, donated to Havnar kirkja (1788; rebuilt 1865), also known as the Tórshavn Cathedral, by surviving members of the crew (Figure 25). Besides holding some of the Faroe’s most detailed ship models, Tórshavn Cathedral established the formula that would be replicated in parish churches throughout the country: entry through a gabled porch and vestibule before passing through the doors to a narrow nave, with a gallery on the western end, and choir on the east (Figure 26-28).

Figure 25. A view of one of the detailed ship models in the Tórshavn Cathedral.

Figures 26-28. Views of the interior and exterior of the multi-colored Tórshavn Cathedral.

Select parish churches function as defacto museums, housing important artifacts to local and national history. To provide curious visitors access, the keys to such churches are typically held by local elders, with directions to their home or a phone number taped to the church’s door. Arguably one of the most prized Faroese treasures held outside of the National Museum is the original flag (Figure 29) of the Faroe Islands, nicknamed the Merkið, which resides in the church of Fámjin on the southernmost island of Suðuroy (Figure 30 and Video 6).5

Figure 29 and 30. Jens Olivver Lisberg and his friends designed the flag and first raised it over the church in 1919 but it was not officially flown until April 25, 1940. Prompted by the Germany occupation of Denmark, the British government sent a convoy to the Faroes to prevent Axis occupation. Banned from sailing under the Danish flag, a Faroese ship bound for Aberdeen raised the very same Merkið that is preserved behind glass in the church.

Video 6. Drone footage of the Fámjin on Suðuroy, Faroe Islands, home to the church that houses the nation’s first flag.

Despite the typical arrangement and relatively predictable features of Faroese churches, there are a handful of religious architecture anomalies in the islands that help make each town, sometimes separated by only ten kilometers, distinctive and memorable (Figures 31–34).

Figure 31. The stone church in Eiði on Eysturoy was constructed around 1881 and features some of the more elaborate, albeit garishly painted, doors in the Faroe Islands.

Figure 32. The church at Sandvík on Suðuroy has an octagonal tower and roughcast over stone, sourced from the adjacent quarry.

Figure 33. Perched above the basalt columns of Tvøroyri on Suðuroy, the wooden components of the local church was prefabricated in Norway then shipped to the town for construction in 1908.

Figure 34. Oddly proportioned and built in the neo-gothic style, the church at Vágur on Suðuroy was constructed in 1939.

The Tale of Two Cities: Klaksvík and Tórshavn

Since I flew to the Faroes, driving to Klaksvík, Borðoy, shortly thereafter and departed the islands via ferry in Tórshavn, the two largest cities on the islands essentially formed bookends for my visit. This, in hindsight, was serendipitous since Klaksvík and Tórshavn are atypical sites in the Faroes due to their scale, urban density, and the amount of new construction underway. Unlike many of the traditional Faroese towns scattered across the islands’ winding coastlines, Klaksvík and Tórshavn are disconnected from the formula of bøur and hagi. Instead, these cities are pushing forward with trade ambitions, expanding their deep natural harbors to receive cargo and cruise ships (Figure 35).

Figure 35. A panoramic view of Tórshavn illustrating the varied topography and architecture of the capital’s harbor region.

New concrete, glass, and basalt-clad towers are rising along the harbors and unlike other parts of the islands where homes and agricultural structures that have outlived their purpose are left to weather and deteriorate in the elements (Figure 36), scaffolding fills the streets and alleys of Klaksvík and Tórshavn in support of restoration and preservation projects (Figure 37).

Figure 36. An architectural ghost near the harbor of Nólsoy, with a re-cladding project in the background that shows the stained pine board before it receives a new coat of paint.

Figure 37. A view of the conversion of a fish processing plant in Tórshavn, with traditional Faroes homes and midcentury housing blocks in the background.

Although home to a population of just 5,000, a quarter of the size of the capital of Tórshavn, the city of Klaksvík felt absolutely metropolitan in comparison to other towns I passed en route: there were several stores and gas stations, a brewery, and an active harbor in the center of the city.

Figure 38. An aerial view of Klaksvik, showing the city nestled between the mountains and two fjords.

Vikings settled in the area for its rich potential as a natural fishing harbor between two, deep fjords (Figure 38). With a varied terrain featuring the majority of the Faroe's tallest peaks, the northern islands were largely detached from the more populous islands of Eysturoy and Streymoy until the Norðoya tunnel opened in 2006, connecting Klaksvík to Leirvík on Eysturoy. Therefore, until the last decade, Klaksvík provided all of the essential services for the northern islands: it was named an independent municipality in 1908 and it has been home to a hospital since the 1890s, a hydroelectric station opened in the 1930s, and a technical college was founded in 1936. Klaksvík grew substantially in the early 20th century with the rise of the fishing industry due to the introduction of steam trawlers in 1911 and the foundation of a national steamship company in 1919. The Faroe Seafood Export Company followed a decade later and the latter half of the twentieth century saw the rise of fish processing plants until the ‘Black October’ crash of the nation’s fishing industry. Revived by rising fish stock, the discovery of oil, and the newfound tourist industry, now the second-largest economic generator in the nation, the cranes of working in the primary cities of the Faroe Islands indicate ambitions to grow the population, industrial enterprise, and support a new influx of travelers.

Beyond its distinction as an urban center, Klaksvík also has a few key constructions that help reveal aspects of the nation’s history and the northern city’s aspirations for future growth, ranging from recreational facilities to the largest religious structure on the islands. Unlike Iceland, where even the smallest of municipalities have a thermally heated community pool, the Faroe Islands do not have hot springs. Heartily, many Faroese swim in the North Atlantic, since only Klaksvík and Tórshvan offer indoor swimming pools. The remnants of Klaksvík's early swimming pools, the first in the Faroe Islands and built in 1902, are still visible along the southeast coast of the city (Figure 39). These waterfall-fed pools were replaced with a downtown, indoor Aqua Center in 1974 and the facility recent underwent a renovation.

Figure 39. An aerial view of Klaksvík’s abandoned swimming pools.

Not far from the center of the city is Christianskirkjan (1963), an Evangelical Lutheran church designed by Danish architect Peter Koch in the style of a Viking Hall and built to accommodate 1,000 (Figures 40 and 41).

Figures 40 and 41. Built in the Norse style, the wooden bell tower of Christianskirkjan is detached from the seven bay sanctuary.

The stone and slate exterior with a gable roof punctured by tall, transverse windows shelters a triple height nave with exposed wooden framework. The warm tones of the stained wood, with intricate joinery details as well as tongue and groove panels, contrast with the cool, chamfered columns and beams that support the roof and two-tiered gallery. Raised high above the parishioners, nearly blending into the shadows of the wooden ceiling, is an 8-oar grindboat (Figure 42). Unlike the scaled modeled of wooden fishing boats and ships that hang from the ceilings of smaller parish churches, Christianskirkjan’s vessel is a historic artifact and an ever-present reminder of the perils, and marvels, of the sea: the wooden boat was the only one to survive a storm in 1913 that claimed the lives of all but two fishermen from Skarð on Kunoy. Following the accident, the remaining inhabitants moved to Haralssund, Kunoy, and Klaksvík.

Figure 42. A grind is a school of pilot whales and hunts in the Faroe Islands date to 1584. Still part of Faroese culture and advertised as ‘sustainable, regulated and communal’ by the whaling division of the Faroese government, much to the chagrin of animal activist groups and Greenpece, grinds still occur and I witnessed the end of one in while passing through Haralssund. Once a fisherman spots grind, he alerts fellow fishermen to help drive the whales into a fjord where they are beached and their spinal cords are cut with intricately carved, traditional whaling knives.

A notable fresco, a rare medium within the islands’ extant collections, adorns the eastern wall of Christianskirkjan. The work was originally created for a cathedral in Viborg, Denmark, in 1901; however, the damp walls of the church forced the removal of work and it was installed in the National Gallery in Copenhagen before it found a home in Christianskirkjan. Continuing its patronage of religious artwork, Christianskirkjan commissioned local artist-carpenters Edward Fuglø and Sjúrður Sólstein to create a series, entitled Jesus from Nazareth, featuring ten intricately carved wooden roundels. Although the pieces depict stories from the life of Jesus, the artists integrated references to Faroese landscapes and found objects from local fisherman (Figure 43).

Figure 43. Measuring approximately four feet in diameter and nearly a foot deep, the wooden roundels showcase a new method of creative, Faroese carpentry.

Although the harbor at Klaksvík manages some commercial shipping, a new container port was constructed north of the city a few years ago, making Klaksvík a well supplied, yet compact center for commerce on the islands. For the last decade the city hosted the Summerfestivalurin music festival Looking towards future development, the city held an open, international urban design competition for a new city center in 2012. The Danish firm Henning Larsen Architects, winners of the competition, proposed a star-shaped mixed use structure that will provide a new, covered city center that will allow for civic events out-of-doors despite the variable weather. The project also proposed a series of urban canals to better connect business and recreationalists to the harbor. The municipality is still finalizing the full details of the district plan, including the establishment of a new Maritime Museum, but construction for several elements, including a new residential block with ground story commercial space, broke ground in the summer of 2015 (Figure 44). It is anticipated that by 2017 the dramatic transformations of Klaksvík’s urban center will be in full effect.

Figure 44. The four story mixed-use block will offer new residents uninterrupted views of the surrounding mountains and access to the new, urban canal system and semi-conditioned town square.

Tórshavn, literally translated as ‘Thor’s harbor’, is the smallest capital in the world in terms of land area and contains the only traffic lights in the Faroe Islands (Video 7). Located on the southeastern coast of Streymoy, it proved to be a convenient base for exploring the rest of Streymoy and Eysturoy as well as the southern portion of the nation. As the largest city, Tórshavn is home to approximately 40% of the nation’s inhabitants as well as a free city bus network that serves the suburb of Hoyvík.

Video 7. Drone footage of the capital city, Tórshavn on Stremoy, Faroe Islands.

As a settlement with Viking roots and a quickly expanding commercial harbor, the city presents a series of compelling, yet disorienting, contrasts in terms of technology and aesthetics. For example, the narrow winding streets of the Tinganes, the site of the area’s parliament since 825 and the old warehouses of the Royal Trade Monopoly, are situated in the heart of the harbor where traditional wooden boats dock next to modern trawlers with sonar and wind turbines (Figures 45–49). Twice a week, the oak schooner Norðlýsið sails to explore the caves of neighboring Hestur, passing the billows of smoke from the massive Smyril Line ferry Norrøna and container ships in Vestarvá harbor along the way. Perched above this scene is the Skansin fort, originally constructed in 1580 to protect the harbor from pirates and rebuilt in the early 19th century following a series of attacks by Turkish and British forces. Today, like Tinganes, the fort is preserved as a tourist destination, frozen in time (Figure 50) while the sprawl of Tórshavn continues into the hills, populated with newer structures: modern housing blocks, the community resource and celebration of Scandinavian design and culture known as the Nordic House (1983), and the nation’s only array of big box stores.

Figure 45. An aerial view of the streets and turf-covered buildings of Tinganes.

Figures 46-48. The architecture of the Tinganes has familiar features from Faroese vernacular structures, such as turf roofs and painted wooden cladding, but some of the buildings have costly half-log clapboard and many of the buildings’ foundations have a unique composition of rubble walls, bonded together with shell and lime mortar.

Figure 49. One of the capital’s few hotels is visible in the background, towering above some of the area’s more famous turf-covered restaurants that receive their fresh catch directly from the adjacent harbor.

Figure 50. Some of the best views of the capital can be seen from the star-shaped fort and the lighthouse is one of the most recognizable landmarks of the area.

Although an interesting city with museums and a layered approach to urban fabric that provides insight to the ways the Faroese architecture has evolved, some of the most interesting aspects of capital region are outside of the city. For example, twenty minutes south of Tórshavn is Kirkjubøur, the site of a medieval settlement that was once the heart of the Faroe Islands (Video 8). Now a small town that receives chartered tour buses from the capital, Kirkjubøur has Viking roots but is best known as the site of a cathedral and early seminary.6

Video 8. Drone footage of the medieval town of Kirkjubøur on Stremoy, Faroe Islands.

Prior to the Reformation, the church owned more than half of the land in the Faroe Islands and Kirkjubøur served as the religious and legal seat.7 As a large stone ruin with thick moss-capped walls, Magnus Cathedral (b. 1300) is one of the most striking structures in all of the Faroes (Figures 51-58). Originally commissioned under the patronage of Bishop Erlendur (1269–1308), the project started with great ambitions but locals rebelled over the cost of the structure and slow construction meant that is was unfinished at the time of the Reformation. The use of stone cavity walls, a sacristy with a crumbling spiral stair, pointed arches, and weathered carvings, found on several extant corbels and stone plaques, are unlike anything else in the Faroes. Today, the building is partly sheltered by an ‘umbrella’ of aluminum panels and steel scaffolding in hopes of keeping water from the friable stone and protecting the structure from further erosion (Figure 59).

Figures 51-58. Views of the massive walls and gothic elements of the Magnus Cathedral.

Figure 59. To protect the building from further deterioration, the cathedral’s cap was installed in 2010.

Since Magnus Cathedral was never consecrated, the adjacent stone structure painted white, known as Ólavskirkjan [St. Olaf’s church], serves as the area’s place of worship (Figures 60 and 61). Elements date to the 12th century but due to its location next to the unrelenting sea, the church has been rebuilt and restored several times. In the medieval period, the site was a popular pilgrimage site and was known as the ‘Monk’s church,’ with recent archaeological excavations revealing artifacts such as a Canterbury coin from 1218–1235.8

Figures 60 and 61. Views of the Ólavskirkjan in Kirkjubøur.

From the 1400s to the mid-1800s, the area’s parishioners sat in sixteen pews with richly carved ends (Figures 62–64). These rare artifacts of medieval Faroese craft are now the centerpieces of the national history museum in Hóyvik, known as Føroya Fornminnissavn, and were once the subject of an intense dispute of cultural heritage between the Faroese and Danish governments. Removed to the Museum of National Antiquities in Copenhagen in the mid-1800s, the pew-ends were only returned to the Faroe Islands in 2002 as part of a 400-piece heritage settlement signed in the summer of 1999.9

Figures 62-64. Details of the Kirkjubøur pew-ends.

Finally, the last site in the rich triad of Kirkjubøur architecture is a preserved farmhouse from the 11th century, known as the Roykstovan (Figures 65–70). As one of the oldest, continually inhabited wooden houses in Europe, the Roykstovan now functions as a hybrid structure, with a living history museum in a part of the building and a family residence in the other.10 This creates an interesting, experiential contrast for visitors with the opportunity to explore the details and wares of a traditional home while listening to the sounds of a vacuum cleaner running in an adjacent room and children playing beneath the farmhouse’s various overhangs. This juxtaposition of medieval and modern life is particularly compelling considering that the Patursson family currently residing in the Roykstovan are the seventeenth generation to call the structure home.

Figures 65-70. Views of the Roykstovan, with stone foundations quarried from the neighboring hillside, logs imported from Norway, and an interior depicting farm life in the 19th century.

Prospecting Tourism in the Faroe Islands

Although weather interruptions to ferry schedules spoiled several planned excursions, I was able to traverse the large extent of eleven of the eighteen Faroe Islands. Successful drives and ferry trips around the northern and southern regions provided glimpses of the coastlines of all but Mykines and Fugloy (Map 3).

Map 3. The dark fill on the map identifies the sections of the Faroe Islands archipelago that were explored during the island travels.

Never more than five kilometers from the sea, the Faroe Islands are filled with carefully built vernacular structures that mediate a harsh climate while blending into the landscape through their low profile and turf-covered roofs. These architectural traditions continue in new architectural projects around the island and since the contemporary trend of green roofs has much deeper roots in the Faroes, several structures experiment with new forms and prefabricated solutions for sustainable architecture in the rapidly growing country (Figure 71).

Figure 71. These geodesic vacation homes (2000) near Sørvágur, Vágar illustrate a new era in Faroese architecture that blends vernacular precedent with new materials and forms. Designed and marketed by a Tórshavn-based architecture firm, Easy Domes Ltd., the homes come in a prefabricated kit of twenty-one panels that can be constructed on almost any site with specially designed fasteners.

With one of the highest birth rates in Europe and the desire to expand the tourism industry, the Faroes are poised to reshape the nation in the twenty-first century but it will, hopefully, not come at the cost of abandoning the self-sufficient community structure found in the small villages, tucked within the picturesque fjords of the islands.

Bibliography

An Historical and Descriptive Account of Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands. New York, NY: Harper & Brothers, 1844.

Hróarsson, Björn, ed. Faroe Islands Today. Kópavogur: Printskill, 2008.

Proctor, James. Faroe Islands. Chalfont St. Peter: Bradt Travel Guides, 2013.

Schei, Liv Kjörsvik, and Gunnie Moberg. The Faroe Islands. Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2003.

Swaney, Deanna. Iceland, Greenland & the Faroe Islands. London: Hawthrone for Lonely Planet, 1997.

Wylie, Jonathan. The Faroe Islands: Interpretations of History. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1987.

1 Björn Hróarsson, ed. Faroe Islands Today (Kópavogur: Printskill, 2008), 127.

2 Statistics provided by the Visit Faroe Islands Tourist Board.

3 An Historical and Descriptive Account of Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands, (New York, NY: Harper & Brothers, 1844), 317-24.

4 Deanna Swaney, Iceland, Greenland & the Faroe Islands (London: Hawthrone for Lonely Planet, 1997), 533.

5 Liv Kjörsvik Schei and Gunnie Moberg, The Faroe Islands (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2003), 40.

6 Ibid., 74.

7 Jonathan Wylie, The Faroe Islands: Interpretations of History (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1987), 13.

8 Schei and Moberg, 130.

9 Ibid., 244.

10 James Proctor, Faroe Islands (Chalfont St. Peter: Bradt Travel Guides, 2013), 64.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top