-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Cities and Celebrations in Snow: An Introduction to Tourism in Japan

Danielle S. Willkens is the 2015 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs and videos are by the author, unless otherwise noted.

My first few weeks in Japan have been filled with travels around Hokkaido, the northernmost island and largest of Japan’s forty-two prefectures, as well as some of the colder regions of Honshu. With this itinerary, I visited three of the snowiest cities in the world and this allowed me to experience some of the sites and events associated with Japan’s famous snow festivals (Figure 1). Navigating icy conditions in both urban areas and on mountainous slopes with crampons strapped to my boots the unwelcome souvenir of a sprained ankle from Cuba, has been a challenge but memories of the warm Caribbean sun kept most shivers at bay on the coldest days.

Figure 1. A ski jump and moguls temporarily installed in the center of Sapporo.

Although dramatically different in terms of climate and culture, 2016 marked the largest visitor numbers for all three of the selected islands for this study sponsored by the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. Like Iceland and Cuba, the number of tourists to Japan has nearly doubled since 2012. However, unlike the previous two nations on my travels, only a small number of visitors to Japan come from the United States, tourism is not a main economic driver at only 10% of the nation’s GDP, and as a much larger nation than Iceland or Cuba, geographically and in terms of population, Japan has many more national tourists.1 Nonetheless, leveraging an incredibly efficient system of public transportation and network of accommodations, with growing interest in room sharing possibilities like Airbnb, Japan hopes that the promotion of omotenashi [Japanese hospitality] will grow foreign tourist numbers as the nation looks towards hosting the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo. More than 50% of the venues for the Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics will use existing structures, some of which were constructed for the 1964 Olympic Games. These sites, along with some cultural heritage sites that will feature heavily in the tourist landscape of the games, will be discussed in a future post since Japan hopes to reach 40 million tourists in 2020, a massive and ambitious increase from last year’s unprecedented 24 million visitors.

Aside from the government’s cultivation of tourism, the development of apps by both Japanese and foreign software companies are also helping to entice visitors and assist with navigation. Like other cities, a number of guidebooks are available as apps and e-books but other apps specifically highlight the architectural heritage of the island. The Japan Architecture Map provides geo-location and basic information for about 6,000 projects, providing a useful compliment to other guidebooks and architectural history references since it predominantly covers projects from the midcentury to the present. Although English signs are prevalent in major cities such as Kyoto and Tokyo, Google Translate app’s instant camera translation option has been extremely useful for labels and museum signage. The app also helps highlight the problems of overly stylized typography: as a pet peeve of many designers, these graphic embellishments do not work with the app’s dynamic recognition system.

Learning Curves and Sukiya2

Through both the study and design practice, I was aware of the many spatial and structural differences between traditions in Western and Japanese architecture. However, no amount of reading, documentary screenings, or visits to period rooms or 'eastern-inspired' sites could have truly prepared me for the experience of Japanese architecture.3 After only a few weeks, I find myself entirely enthralled and, as a very eager student, I find myself needing to learn an entirely new architectural language. This is not just in terms of the vast, associated vocabulary but also in relation to the basic components of architectural composition for Japanese architecture prior to the 1870s. After this time, Japan experience the forced expansion of international trade and the end of sakoku [imposed seclusion]; the subsequent influx of Western architectural influence during the first period of ‘modern’ Japan in the Meiji Era (1868-1912) dramatically changed the nation’s built landscape and its perception of architectural tradition (Figure 2).4

Figure 2. Layers of spaces and signature use of shadows within a portion of a noodle shop from the Hokkaido Historical Village. The decoration shows a mixture of Japanese and Westerns items during the early Meiji era. In both residential and civic architecture, the proportional relationships between floor and ceiling differ from Western. In my attempts to capture the interiors of 'traditional' Japanese architecture, it has been necessary to sit or kneel in many spaces to actually capture a representative photograph whereas verandas, used for circulation, require a standing pose.

The form, materiality, and structure of walls are different since the concepts of post, beam, and cladding are redefined. The labels of 'door' and 'window' are no longer applicable because of the layered and flexible approach to enclosure, such as tsumado [side doors] and shoji and fusuma screens. I am beginning to understand the incredible variety associated with the screen and I find that it is necessary to return to the fundamental term of 'aperture'. The modularity and materials form distilled spaces that, although simple and even bare at first glance, are infinitely fascinating in their attention to detail, proportion, and their relationship with the greater site, visually and climatically.

Scottish architect and ornamentalist Christoper Dresser (1835-1904) was one of the first designers to explore Japan and his three months of travel in 1876 and 1877, covering more than 2,000 miles, were recorded and published as Japan: Its Architecture, Art and Art Manufactures (1882).5 The foreword initially apologizes for adding to the already voluminous record of material on Japan from a Western lens, but he explains that his motivation was to look from a design perspective and “observe what an ordinary visitor would naturally pass unnoticed.”6 I have found that the time and detail Dresser devoted to examining and drawing even the smallest details has been a useful reference for my own investigations and a source of inspiration for certain on-site sketching exercises:

With these nails I am positively delighted, and I feel constrained to stay and note their forms in my sketch-book (sic); yet while thus engaged I know that I am a drag on my companions. But here we have not only nails but hinges—grand hinges—hinges two to three feet in length. And besides hinges we have metal plates and bindings on the doors. In Nara the old metalwork would supply the art student with material for study, and examples to copy, for weeks.7

Frozen Architecture8

Hokkaido is the northernmost prefecture in Japan and it is often characterized as a pioneering area of Japan because of the cold winter climate and rough terrain. It, too, was a place that experienced Meiji era ‘modernization’, transitioning from an island of fisherman to one with several pop-up cities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that were based on speculative industries, such as mining and even beer brewing (Figures 3 and 4). The Hokkaido Development Commission was established in 1869 to jumpstart this ‘modern’ development on the island, harnessing local resources. To assist with this endeavor, the Commission started the Sapporo Agricultural College, now known as Hokkaido University, and one of the educational institution’s historic buildings serves as one of the most historic landmarks of downtown Sapporo (Figure 5).

Figures 3 and 4. The first brewing operations of the Kaitakushi Brewery, later known as the Sapporo Brewery, started in Tokyo but operations were moved to Hokkaido in 1870s when the company realized the cold weather of the northern island was perfect for brewing and provided ease access to ice for shipping. The company’s operations were modernized in 1894 and visitors to the Sapporo Beer Museum, opened in 1987, can walk though a repurposed boiler house and storehouse. Although all of the displays are in Japanese, the museum provides laminated sheets in an array of languages for each of the interpretive boards. With a holistic approach to the design and information relayed within the concise museum area of the complex, the display boards were attached to cleanly welded frames and thoughtfully illuminated to appear as if these industrially inspired objects are floating above the refinished warehouse floors.

Figure 5. Now known as the Tokeidai [the Clock Tower] (1878), Development Commission architect Kikou Adachi originally designed the structure as the multi-functional military drill hall for the Sapporo Agricultural College. It housed lectures, a specimen room, gymnaicis, and the annual graduation ceremony that celebrated a new cohort of Japanese scholar-farmers who were equipped with the skills and practical knowledge to help develop Hokkaido’s resource-rich landscape. This building, as well as the former Hokkaido Governmental Building and many other historic structures in the city, has a red star that was symbol of the Hokkaido Development Commission.

One of the primary reasons that my time in Japan started with a visit to the north during the coldest time of the year was the motivation to experience the ephemeral architecture of the Sapporo Yuki Matsuri, the annual Snow Festival (Figures 6-11). This year marked the 68th for the festival that occurs during the first few weeks of February. The popularity of the festival resulted in the expansion of the program and it now entirely dominates the central areas of the city, occupying three main sites: massive state-sponsored sculptures in snow and ice line the linear park of Odori, smaller sculptures and competitions occur at Susukino, and the Tsu Dome transforms into a field of slides and winter games, primarily for children. Restaurants and other businesses along the streets of Sapporo also join the festivities by commissioning sculptures and other decorations for their properties. Although occupied with playful sculptures in snow and ice during early February, the Odori site plays an important role in the urban planning history of Sapporo since it once served as the street dividing the various regions of the gridded city: the residential district to the south, the governmental district to the northwest, and the industrial district to the northeast.

Figures 6 and 7. Views of the snow festival at night.

Figure 8. A detail from the elaborately sculpted entablature of the Arc de Triomphe.

Figure 9. Walking around the expansive grounds of the Odori site one morning, I had the chance to speak with a number of the festival's volunteers and master craftsmen and women who were eager to explain the differences between working with snow and ice for the creation of such astounding yet temporary sculptures. Ice, they explained, was much more forgiving: with the proper tools and skills, melting, repairing, and refreezing could correct an error or structural inaccuracy. Such repairs are nearly impossible with snow so mistakes could be entirely detrimental to the integrity of the sculpture.

Figure 10. A visit to the top of the Sapporo TV Tower provided one of the best views of the Snow Festival along the Odori Park.

Figure 11. The former Hokkaido Governmental Building (1888), also known as the Red Brick Office, serves as a local history museum, archive, and the grounds serve as winter wonderland for visitors to build their own snow sculptures.

This year, the largest sculpture in snow was a 1:3 replica of the Chukondoh [Central Golden Hall], located within the Kohfukuji Temple complex of Nara (Figure 12). Originally constructed in the Hein Period, the building experienced several fires and an extended period of decline from 1717 that resulted in a disassembly project in 2000. However, this process led to the unexpected archaeological discovery of the foundations of the original Central Golden Hall and the reconstruction should be completed by the fall of 2018. Although a fraction of the scale, the Chukondoh-in-snow had carefully articulated architectural elements, directly modeled on known details from the original temple such as onigawara [end tile with fearsome looks] and miteuke [structural joints comprised of various, stacked blocks] (Figure 13).

Figure 12. At night, the project became a stage for events and games.

Figure 13. A detail of the Golden Hall’s craftsmanship-in-snow.

Constructed of 3,000 tons of snow that was modeled into 4,500 blocks and sixty different, modular pieces, the temple was fabricated by members of the military's Self-Defense Forces Operation Platoon who received guidance from approximately twenty skilled snow and ice sculptors. To undertake such a large and intricate project the team built a miniature version of the temple in December and this mockup helped the team identify specific molds that needed to be constructed for repetitive pieces in the full-scale iteration. Scaffolding was erected in early January then the team began the construction of a snow foundation before they started the three-week process of laying ice blocks and carving details with picks, chainsaws, and special sculpting tools. Throughout the two weeks of the Snow Festival the team conducted regular inspection and maintenance and on February 13th the temporary monument, along with the rest of the festival's structures, was demolished.

Sapporo is the most famous city for the celebration of ‘snow-itecture’, but several other sites take advantage of the cold weather to attract visitors. Although castles are picturesque in the snow, icy conditions on the fortification’s grounds can be a deterrent and visitor numbers typically decline in the winter months. For Hirosaki Castle (b.1603), however, early February is one of the busiest times because of the Yuki-Doro [snow lantern festival] (Figures 14-16). Since 1977, the castle’s grounds have been home to the construction of large-scale lanterns, celebrating the region’s cold winter and taking advantage of the shortened period of daylight. My visit to Hirosaki Castle, fortuitously, coincided with National Foundation Day so I was able to explore the grounds for free, observing the area in both daylight and nighttime illumination. Navigating the slippery grounds, it was clear that children had the best means of transportation with their small, plastic sleds. Nonetheless, the more than 200 lanterns and 300 igloos, combined with the dramatic lighting of the castle, gatehouses, and colorful bridges over icy moats made the skids and occasional falls worth the trek.

Figures 14-16. Vibrantly painted rice paper covers many of the lanterns, casting a colorful glow on the snowy paths and sculptures, while the simple ‘igloos’ create a field of light set within a dramatic backdrop.

Besides the famous lantern festival, Hirosaki Castle is currently benefitting from a rise in tourist numbers because of the interest in a structural stabilization project. In 2015, the castle was moved to an adjacent site due to shifting foundations from earthquakes in 1983 and 2011; the current Google Maps satellite image of the castle grounds actually shows the structure mid-move during the 2015 Cherry Blossom Festival. A team is meticulously repairing the original, laid stone foundation of the castle and hopes to finish by 2021 (Figure 17). At that time, the castle will be returned to its original site and additional stabilization and restoration projects will continue through 2026.

Figure 17. The individual stones of the foundation have been numbered for accurate reconstruction and a temporary platform now sits between the original castle site and its temporary home, giving visitors the opportunity to view the ongoing work from an elevated position.

As evidenced by events in Sapporo and at Hirosaki Castle, certain sites are leveraging the region’s heavy snow to lure visitors from busy ski slopes of northern Honshu and Hokkaido to urban and historic areas. Nature tourism, too, is experiencing an increase in winter visitors (Figures 18-19 and Video 1). Several tour companies and local buses transport visitors from neighboring cities to onsen [hot spring] sites in Yamanouchi, Nagano Prefecture. A key attraction in this region is the Jigokudani Park in the Joshinetsu Kogen National Park that is home to a troop of more than 150 Japanese macaques, commonly known as snow monkeys. The park was established in 1964 but a railway company recently purchased it and, consequently, the physical and tourist infrastructure of the site have been improved in the last two years. At some point, while fingers and toes lose feeling due to the frigid temperatures, one has to wonder who the real ‘wild animals’ are at the site: the monkeys enjoying the natural hot springs in their custom-built pool or the visitors paying entrance fees to trudge miles through the snow.

Video 1. A trek through the forest to watch snow monkey hijinks.

Figures 18 and 19. Visitors crowd the hot springs for close views of the snow monkeys but the site has controlled access and watchful staff, safeguarding the monkeys and their habitat.

Festival Sites, Out of Season

Visits to the Sapporo Snow Festival and other northern sites such as the Yama-dera are entirely compelling in the snow, yet time in conditioned museums and historic sites in the Hokkaido and northern Honshu were welcome places to escape the cold temperatures and strong winds (Figures 20 and 21).

Figure 20. Easily accessible from Sendai, Yama-dera is known as the ‘mountain-temple’ but it actually contains a series of temples, garden shrines, and a number of stone Jizō, a Buddhist guardian of travelers and children. The climb to the top of the mountain consists of more than 1,000 steps and in the winter they are packed with snow and ice, making the pilgrimage to the top quite an exertion and the return trip to the bottom a series of treacherous slides.

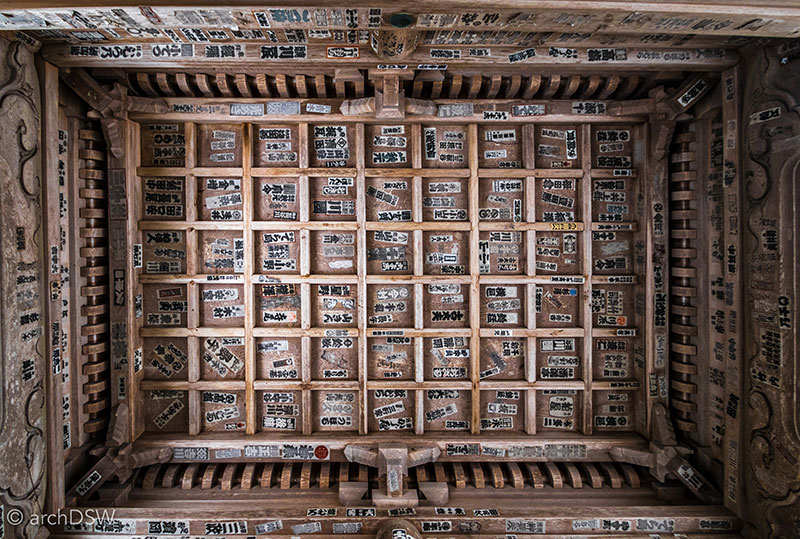

Figure 21. Senjafuda [shrine tags] adorn the gates and temples throughout the site.

The Nebuta Museum Wa Rasse is one of the many examples of facilities that provide a warm space to explore the products of Japan’s numerous festivals, outside of the specific event’s celebration season (Figure 23 and 24). In 2002, the Canadian firm Molo, with lead designers Stephanie Forsythe and Todd MacAllen, won a competition to design a display space for some of the famous, large-scale floats from Aomori’s August festival (Figures 24 and 25). The festival dates to the 8th century and consists of nebuta: large, sculptural lanterns made from vibrantly painted washi paper that is stretched over frames of wire and bamboo (Figures 24 and 25). These constructions, depicting historical and mythical stories, can reach nearly thirty feet tall and up to sixty feet long. Paraded through the streets with a team of coordinated handlers, contemporary floats are illuminated with intricate systems of light bulbs for nighttime display and some of the floats are even designed to float down a stretch of the Oirase River adjacent to Aomori.

Figure 22 and 23. Views of the Nebuta Museum.

Figure 24 and 25. Views of the nebuta and its underlying structural system.

Since 2010, five of each year’s best floats are selected for yearlong display in the Nebuta Museum. In addition to the changing exhibits, the museum displays the history of the parade and the nebuta tradition as well as a series of ‘head’s by designated nebuta masters (Figure 26). For the design of the museum Molo, a firm now known for their soft shelters and expandable paper furniture, enlisted d&dt Arch, Frank la Revière Architects Inc. and structural engineer Kanebako were later added to the project team. Together, they created a building within a skeletal framework of 'red steel ribbons' and this form creates a modern reinterpretation of an engawa [veranda]. Unlike the engawa of traditional homes, the museum is not elevated or made of wood. Instead, a series of roughcast panels sit on a gravel bed, mediating a slopping site and allowing the large floats to slip through the designed gaps in the screen and into the exhibition space after passing through the building’s large, concealed doors. Situated along the river and surrounded by large piles of snow, the screen looks more like a large curtain rippling in the cold wind than an element of building enclosure.

Figure 26. The larger-than-life heads line the museum’s corridors.

Although few festival museums have an architectural enclosure as captivating as Aomori’s, other cities allow visitors to explore festival culture out of season. For example, in Takayama, a historic city described in more depth later in the post, visitors can see elaborate Edo-era floats and karakuri [automatons]. In town, visitors can explore the Festival Float Exhibition Hall, adjacent to the Sakurayam Hachiman Shrine. The Takayama float festivals occur each autumn and spring, with eleven or twelve floats parading through the narrow streets and the cross colorful bridge of this Edo-era merchant town. The floats were typically stored in yatai-gura [storehouses] in the town, with thick, plastered walls and tall doors to accommodate the float's height. Some of these storehouses are still visible in the town and several are still in use but a rotating array of floats occupy the Festival Float Exhibition Hall to allow visitors a closer look at the carved elements, gilding, and lacquer of these large and impressive constructions (Figure 27). As illustrated in the exhibit’s interpretive boards, event elements not visible to parade-goers, such as the float’s interior panels, were decorated to create a total work of art. It is hard to imagine that some of the floats dating to the 17th century were even decorated with precious gems and the wonderment associated with these structures multiplies with the addition of marionettes that, through the coordinated operation of thirty-six strings, could dance and perform acrobatics. The floats are displayed behind large glass panels and a ramp around this enormous jewel box allows visitors to view the floats from various heights, with costumed mannequins serving as useful scale figures. Since visitors cannot get too close to these preserved floats or see the marionettes in action, the city of Takayama commissioned another festival site. Reached by local bus, Matsuri no Mori ‘Festa Forest’ outside of town is a large, underground structure that houses contemporary reconstructions of lacquered, Edo-era floats (Figure 28). The practice of float reconstruction helps ensure that the traditional crafts associated with float making are preserved across generations. In addition to the six floats, with timed performances of the float’s robotic marionettes, the site has modern day karakuri including three large taiko drummers. In addition to being examples of master craftsmanship, some of the floats in Takayama are part of the newly minted ‘Yama, Hoko, Yatai, float festival in Japan’ addition to UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage List. Designated in late 2016, the floats join a list of 300 other ‘intangible cultural heritages’.

Figure 27. A view from the elevated platform in the Festival Floats Exhibition Hall.

Figure 28. Like the Nebuta Museum, the darkened conditions of the Festa Forest highlight the float’s lanterns and reflective surfaces.

Urban Architectural Collections and Reconstructions

This post could easily feature an array of museum sites in Hokkaido or northern and central Honshu since these areas are filled with a rich array of historic sites and collections but I will, instead, conclude this month’s post with a contrast between two different heritage conditions I experienced in February in Japan: Takayama, a town as a living museum, and Hokkaido Historical Village, an open-air museum featuring a recreated series of towns. The first allows visitors to experience two eras simultaneously, such as shops and homes from the Edo era while having easy access to public transportation and modern conveniences, and the second entirely transports visitors to another time and place.

Once an Edo era castle town, Takayama in Gifu prefecture, came under the control of the Tokugawa government in 1692. As a center for the region’s timber production, Takayama developed into a city with refined wooden architecture as well as a center of commerce for the cloth trade, woodworking, and sake brewing. Today, it is a city of museums that celebrates the merchant class, the float-making tradition, and still has seven active sake breweries (Figures 29 and Video 2). It offers visitors the opportunity to explore urban and rural heritage sites, serving as a microcosm of Japanese architectural heritage, traditional craftsmanship, and innovative design.

Know as ‘little Kyoto in Hida’, the preserved areas of Takayama are composed of three main historic districts: Sanno-machi, Ichino-machi, and Nino-machi. These streets are lined with two-story wooden homes, covered in cedar shingles, and shallow rainwater collection lines running to the canal.

Figure 29. Water for the city comes from the nearby mountain springs and this is one of the reasons Takayama became known for its sake. During the forty-five day brewing cycle in January and February, visitors can enter one of the city’s breweries, beneath a newly hung sugidama [cedar ball], to take a tour and try the flowery, unpasteurized sake that Edo era occupants once consumed

Video 2. A walk through some of the preservation districts and shrines of Takayama in the Gifu Prefecture.

In many senses, the preserved streets of Takayama feel similar to Narai-juku (Figures 30-31 and Video 3). At approximately one kilometer and sited along the Narai River, Narai-juku is the longest, preserved post town along the Ero era Nakasendo Road that once connected Edo [Tokyo] and Koto. Designated as an Important Preservation District for Groups of Traditional Buildings in 1978, the historic area of Narai-juku consists of a streetscape of wooden townhouses, anchored by the Sennen-ji Temple on one end and a reconstructed version of the Sizume Shrine on the other. Once known as the primary town for purchasing lacquered products, especially bowls and combs, historic structures have distinctive signage advertising wares and overhanging eaves that shelter the entryways to shops and offices. Although the site is a popular destination for tourists and hikers alike, and is often used for filming period pieces, Narai-juku was a ghost town during my visit due to a local event in a neighboring town.

Figures 30 and 31. Views of Narai-juku and the play of light from the textured wooden surfaces and screens.

Video 3. Travel on Japanese Rail lines between Nagano and the Edo era post town of Narai-juku.

Unlike the small scale of Narai-juku, Takayama contains the historic town as well as a series of shrines following a mountain path to the castle ruins, a modern town with several high-rise hotels, a midsize train station, and several museums in the city and its environs, ranging from preserved historic sites to a private collection of early 20th-century decorative arts objects that was recently converted into a public museum. The Takayama Jinya (1692-1898), one of the oldest preserved government houses from the Edo era, is a substantial site that was in regular use until it was converted into a museum in 1969 (Figure 32). Since then, several restoration and archeological projects have allowed the site to expand interpretation on the walled complex and its guardhouse, offices, and newly reconstructed storehouses. With more than sixty offices as well as facilities for scribes, the governor, and his support staff, the site is a complex one to explore. The massive ohiroma [conference room] has forty-nine tatami mats and could be divided into three different rooms, proving that flexible office space was not just an invention of the modern era. Although a large complex, the details of the site are no less thoughtful than a teahouse or small dwelling: layers of screens separate spaces, engawa line inner courtyard gardens, and 152 mamuki usagi conceal the timber structure’s nails and were intended to bring happiness to the building’s occupants (Figure 33). Integrating digital technology into the site, the oshrasu [civil law court] and ginmisho [interrogation room] used an app called Tabido for an augmented reality experience, showing visitors what the rooms may have looked like while in use during the Edo period. However, poor connectivity in the structure caused connection issues, proving that some of the most enterprising ideas often have technical difficulties in practice.

Figure 32. A view of the wall enclosing the complex and one of the offices

Figure 33. A view into one of the many inner courtyards of the complex, illustrating the seamless connection between inside and outside.

Several extraordinary house museums also occupy the historic districts of Takayama and two were of particular interest: the Kusakabe Mingei-kan Heritage House (1852, reconstructed in 1879 after a fire) (Figures 34-37) and the Yoshijima House (1907) (Figure 38). The merchant house of Kusakabe Mingei-kan was constructed by lead carpenter Jisuke Kawashiri the expansive network of beams and columns have been darkened by years of charcoal burning in the irori [open hearth]. With the family rooms of the home, the lack of clutter means that the eye is drawn to the details of construction: each joint and layer of paper within the shoji screens was considered and every yumihari chochin [bamboo and paper lantern] has a unique construction to illuminate the home, representing an era prior to electrification. Although constructed several decades later, the Yoshijima House has similar features such as tall ceilings and a complex weave of wooden structural members in the lofted ceiling above the home’s store and reception room for visitors. This impressive construction was intended to symbolize the strength and stability of the family and its associated sake business. In both homes, visitors are required to take off their shoes. Although this added to the chill within a space where your breath was already visible, it provided another means of connecting with the site and its history. Moving from stone to polished wood to tatami mats, one became aware of internal rooms' arrangements and hierarchies through not just sight but also touch.

Figures 34-37. Views of the exterior and interior of the Kusakabe Mingei-kan Heritage House.

Figure 38. A series of screens create a Japanese version of enfilade in the Yoshijima Heritage House.

Although beyond the main purview of this post, the decorative arts gem of the Takayama Museum of Art (1997) is not to be missed. Housing a private collection of more than 1,000 pieces of glass and furniture from the Scottish Arts and Crafts and the Vienna Secession movements, as well as the Art Nouveau and Art Deco periods, this purpose-built museum takes full advantage of the site and surrounding mountain views. Designed as a series of intimate rooms, the architecture of each gallery directly responds to the objects within. For example, a cruciform space houses a fountain (1926) by René Lalique that once stood in a shopping arcade of the Champs-Élysées (Figure 39). Each of the four sides of the fountain has a caryatid made of amethyst-colored glass and these Deco figures conceal a metal substructure and the fountain's piping system. Adorning one of the open stairs is a pair of sculptures, once complimented by a painting by Gustav Klimt from the Beethoven Frieze of the Vienna Secession house (1902) by Josef Olblich. On the upper floor of the museum there is a pastiche of period rooms representative of Art Nouveau and the Vienna Succession, with works by Emile Gallé, Otto Wagner, Josef Hoffman, and Kolan Moser. Perhaps one of the most striking rooms of the museum is one that houses a number of authentic and reproduced works by Charles Rennie Mackintosh, inspired by the drawing of a dining room in the 'House for an Art Lover’ competition of 1901 (Figure 40). In advance of the SAH's Annual Conference in Mackintosh’s Glasgow in early June, it seemed particular interesting to see a wood and glass screen from the Hill House as well as a mantel panel from the frieze of the Willow Tea Room. In homage to the Mackintosh collection on-site, the museum's café resembles a reinvented Glasgow tearoom, complete with reproduction silverware, tea sets, and lighting fixtures. Although few guidebooks or even decorative arts journals mention the site, Takayama actively promotes the museum and during the warmer months of the year, a vintage London double-decker bus provides free transportation between the Takayama station and the museum.

Figure 39. Dramatic and ever-changing colored lighting within the room containing the Lalique fountain helps highlight the water feature’s intricate detailing.

Figure 40. Filled with a mix of original and recreated pieces, the Macintosh room blends several of the designer’s favored motifs into one, eclectic space.

As a relatively small city, Takayama is popular with Japanese tourists looking to experience Edo life outside of the bustle of Kyoto but it is a site often overlooked by foreign tourists. Nonetheless, it is an ideal site for its preserved historic districts, museums and for exploring the nearby UNESCO World Heritage sites of Shirakawa-go and Gokayama. Takayama even has an open-air museum focusing on vernacular traditions in the era, the Hida Folk Village (Figure 41-43). The site, organized around a reservoir from 1931, holds several structures designated as National Important Cultural Properties, including a mid-18th century home from Kawai-sho in the northern part of Hida that survived the disastrous earthquake of 1858 and a seiro-gura (Figure 44).

Figure 41. The artificial pond, constructed as a rice patty reservoir, also provided the surrounding homes with a place for recreation and winter ice harvesting. During both visits to the Hida Folk Village, there was freezing rain but the fires within select structures, lit to guard against the chill, helped to add another dimension to the experience.

Figures 42 and 43. The steeply pitched roofs of the vernacular homes were designed with a substantial wooden structure and thick layers of thatch to resist the enormous winter snow loads that would be upwards of eight feet deep in the winter.

Figure 44. This wooden structure served as a storehouse, primarily for food, in snow-laden regions of the nation and the joinery method used to connect the rough-hewn timber allowed the wood to expand in high humidity, insulating the warehouse, and contract in low-humidity to allow more air flow through the building. This passive system helped maintain a relatively consistent temperature throughout the seasons.

The Hida Folk Village is a museum out-of-doors that used the preserved remnants of an early 20th century village as the base for establishing a larger collection of vernacular structures. Homes and storehouses under the threat of demolition were moved to the site and reconstructed, providing visitors the to opportunity explore more than thirty historic structures and, in warmer weather, watch living history demonstrations. Although a rich site on a varied landscape, the scale of the Hida Folk Village pales in comparison to the Historic Village of Hokkaido, outside of Sapporo. Located near the Historical Museum of Hokkaido, a midcentury structure with recently redesigned exhibits that explore the history of the indigenous people of Hokkaido, the Ainu, and the geological composition of the island, the Historical Village of Hokkaido is an expansive open-air museum with more than sixty buildings from the Meiji (1868-1912) and Taisho (1912-1926) periods on a 120-acre site. All of the buildings were moved from sites around Hokkaido to the museum’s property and placed within a series of distinct conditions: an urban setting with a centralized streetcar, a fishing village, a farm village, and a mountain village with a logging pond and canals (Figure 45).

Figure 45. A view of the ‘main street’ in the recreated town. In the warmer months, a streetcar operates between the allée of trees.

Unlike downtown Sapporo, densely packed with tourists and locals exploring the various sights and events associated with the 68th Annual Snow Festival, the Historical Village of Hokkaido was practically empty. In the winter, the site lowers its prices since much of the living history aspects of the museum are in hibernation: there are few, if any, costumed interpreters around the complex and many of the interactive exhibits are under protective coverings. In the warmer months, visitors help bring the buildings and the museum's collections to life: one can make postcards in the early 20th-century printing presses of the post office or participate in a noodle making at a traditional ramen shop. In the winter, the Historic Village of Hokkaido reminds one of a Japanese iteration of Williamsburg, where the majority of buildings are not just authentic recreations but are, instead, historic structures and the doors to all of the historic homes, warehouses, and businesses had been left open for quiet exploration. As someone with experience in museum studies and as a former interpreter at the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Monticello, the idea of an unsupervised historic site is quite unsettling. In spite of this, I was pleasantly surprised to see that of the few visitors I encountered at the site, from various countries and a range of ages, all respected the posted signs and seemed genuinely interested in the content: the sliding wooden doors that sealed most buildings were carefully handled and shoes were removed in exchange for slippers at the sites that required extra care for the preservation of recreated tatami mats and original wooden floors. As a site outside of the urban core of Sapporo, located near the Napporo Forest Park, it takes some purposeful planning to access the Historical Village of Hokkaido with coordinating public transportation so it should not be surprising that those who make the journey are interested in history, architecture, or traditional construction techniques. The deep snow, icy paths, and biting wind also make the site a bit inhospitable in the winter, but for those who make the trek, it was a truly unparalleled opportunity to explore a wide array of building types.

During my visit, the site was akin to a ghost town and the strong winds blowing through the site caused a symphony of eerie sounds in the historic buildings, rattling windows and the protective palettes used to guard the glass from falling snow and ice. Inside, the wind and occasional visitor caused the worn, wooden floors and walls to creak. Although unnerving at moments, visiting during such cold and quiet conditions meant that I had the majority of the structures to myself and, thus, had the opportunity to look closely at original joinery and screen details. The vast majority of interpretation at the museum is in Japanese, but this site is a treasure trove for any architectural enthusiast since almost every building has a small board near the entrance with a detailed plan and brief notes on the building’s original location and its relocation to the museum’s site. Unfortunately, an illustrated tome on the site does not exist in English, so the images below are intended to give a small picture of the village’s rich built landscape and encourage others to make the journey to explore for themselves (Figures 46-54).

Figure 46. Once Sapporo's main Railway Station (1908-1952), this colorful Victorian structure now serves as the gateway to the historic village and houses a small café and shop as well as the main operational offices for the open air museum.

Figure 47. Many of the buildings have a simple latch systems to protect the doors and windows from the site’s strong winds; notice the repurposed mitten that helps protect the lock from freezing.

Figure 48. Serving as a bold marker for the town’s main ‘intersection’, the Brick Police Box operated in downtown Sapporo from 1911 to 1971. Notice the school in the background, discussed in the following caption.

Figure 49. The exhibits within the walls of Hokkaido’s first Junior High School provide a glimpse into education during the early 20th century.

Figure 50. The bold colors and form of the Hirose Photography Studio (1924) are unmatched in the historic landscape: the black and red paint reflect in the snow and the large, glazed roof provided beneficial natural light for the portrait studio.

Figures 51 and 52. One of the first structures visitors encounter on the site is Kondon's Dueing Shop (c.1898) and this building was originally located in the northern city of Asahikawa. In response to the climatic conditions, the building has a double skin of glass and paper screens, affixed to a thickened wooden structure. The glazed panels also have protective wooden shutters on the exterior and the working rooms of this shop were further insulated through the use of a circulation gallery: the core of the building is encircled by hallway, adding an additional layer of protection from the infiltration of cold air.

Figures 53 and 54. Warehouses and multi-functional structures fill the fishing village. Much of this portion of the site, as well as the farming and mountain villages, was inaccessible due to the heavy snow.

Changing Seasons

One aspect of my planned schedule for this fellowship provided the opportunity to spend several months in each country in order to visit certain sites multiple times and experience the changing light, climate, and tourist numbers associated with different seasons. With this in mind, I hope to return to several of the sites referenced in this first blog posting about travel in Japan, exchanging snow piles for cities and sites filled with cherry blossoms. During March and April, I look forward to the celebrations associated with the rites of spring. During this season of renewal, I will visit a number of traditional gardens to study the sakuteiki, the six basic composition elements of Japanese landscape design, as well as the sequence ‘hide and reveal’ employed in miegakure. The spring will also be filled with extended explorations in Kyoto and southern islands, with plans to return to Tokyo for many of the national holidays in May.

Bibliography

Carver, Norman F., Jr. Form & Space in Japanese Architecture. Kalamazoo, MI: Documan, 1993.

Dresser, Christopher. Japan: Its Architecture, Art, and Art Manufactures. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1882.

Gorpius, Walter. "Architecture in Japan." In Katsura: Imperial Villa, edited by Virginia Ponciroli. New York, NY: Phaidon Press Ltd., 2011.

Locher, Mira. Japanese Architecture: An Exploration of Elements and Forms. North Clarendon, VT: Tuttle, 2015.

Nute, Kevin. Place, Time, and Being in Japanese Architecture. London: Routledge, 2004.

Reynolds, J. M. "Teaching Architectural History in Japan: Building a Context for Contemporary Practice." Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 61, no. 4 (2002): 530-36.

Screech, Timon. The Western Scientific Gaze and Popular Imagery in Later Edo Japan: The Lens within the Heart. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Tanizaki, Jun'ichirō. In Praise of Shadows. Translated by Thomas J. Harper and Edward G. Seidensticker. New Haven, CT: Leete's Island Books, 1977.

Taut, Bruno. Fundamentals of Japanese Architecture. Translated by Glenn F. Baker and H. E. Pringsheim. 2nd ed. Tokyo: Kokusai Bunka Shinkokai, 1937.

Ueda, Atsushi. The Inner Harmony of the Japanese House. Translated by Stephen Suloway. Tokyo: Kodansha, 1998.

Yaguchi, Yujin. "American Objects, Japanese Memory; Landscape and Local Identity in Sapporo, Japan." Winterthur Portfolio 37, no. 2/3 (2002): 93-121.

1 The area and populations, in parenthesis, of the nations as of late 2016 are as follows: Cuba 42,430 mi2 (11.27 million), Iceland 39,770 mi2 (323,002), and Japan 145,900 mi2 (127.3).

2 "This term refers to the “abode of empty"; spaces are characterized by the regularity of a structural grid, the use of natural materials, and strong connections between inside and outside.

3 The following readings have been essential to my initial studies: Norman F. Carver, Jr., Form & Space in Japanese Architecture (Kalamazoo, MI: Documan, 1993); Walter Gorpius, "Architecture in Japan," in Katsura: Imperial Villa, ed. Virginia Ponciroli (New York, NY: Phaidon Press Ltd., 2011); Kevin Nute, Place, Time, and Being in Japanese Architecture (London: Routledge, 2004); J. M. Reynolds, "Teaching Architectural History in Japan: Building a Context for Contemporary Practice," Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 61, no. 4 (2002); Timon Screech, The Western Scientific Gaze and Popular Imagery in Later Edo Japan: The Lens within the Heart (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996); Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows, trans. Thomas J. Harper and Edward G. Seidensticker (New Haven, CT: Leete's Island Books, 1977); Bruno Taut, Fundamentals of Japanese Architecture, trans. Glenn F. Baker and H. E. Pringsheim, 2nd ed. (Tokyo: Kokusai Bunka Shinkokai, 1937); Atsushi Ueda, The Inner Harmony of the Japanese House, trans. Stephen Suloway (Tokyo: Kodansha, 1998); Yujin Yaguchi, "American Objects, Japanese Memory; Landscape and Local Identity in Sapporo, Japan," Winterthur Portfolio 37, no. 2/3 (2002).

4 From a vocabulary standpoint, the organization, diagrams and descriptions of Locher’s book have been very helpful. See Mira Locher, Japanese Architecture: An Exploration of Elements and Forms (North Clarendon, VT: Tuttle, 2015).

5 Christopher Dresser, Japan: Its Architecture, Art, and Art Manufactures (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1882). Available online: https://archive.org/details/japanitsarchitec00dres For information on other foreign designers who explored Japan in its early modern years see

8 Since there is little published information on smaller museums and their interpretation, much of the information in the following section is from the actual display boards in the museums. Throughout my travels, I have been heavily reliant on an incredible app called CamScanner to capture images from museums and subsequently generate annotated and organized PFDs. If any readers would like to see captures from specific sites, please contact me by posting a note in the comments section of the blog or by emailing.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top