-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Railroads and Reconstructions: Transportation as a Tourism Conduit in Central Honshu

Danielle S. Willkens is the 2015 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs and videos are by the author, unless otherwise noted.

April was a month of holidays and celebrations in Japan, ranging from Hana-matsuri [Buddha’s birthday] to Easter Holidays that released most schoolchildren from their studies for two weeks.1 These events also coincided with the full blooming of sakura [cherry blossoms] in much of Central Honshu, the region roughly bounded by Kyoto to the west and Tyoko to the east. This means that city parks have been so densely packed with groups of family and friends that patches of grass are barely visible between the elaborate picnic spreads, consisting of blankets covered with assortments of drinks, snacks, and games for young and old. The flowering landscape, holidays, and warmer temperatures of spring have activated urban spaces and revealed a culture of repose that, until this point in my travels, has been absent in Japan. This week, too, is a festive one in the country. The end of April and beginning of May are known as Golden Week and it has four of the nation’s sixteen public holidays: Showa Day (April 29th), Constitution Day (May 3rd), Greenery Day (May 4th), and Children’s Day (May 5th). The last holiday in the sequence is known for its array of carp streamers so I am very much looking forward to the displays.

This month, the majority of my time was spent between Kyoto and Osaka visiting temples, gardens, and museums, with a few trips farther afield to experience sites in different seasons (Figures 1 and 2). Throughout my time in Japan, travels between sites, both historic and contemporary, have been relatively easy to navigate despite language barriers because of apps like Google Maps and the incredible flexibility of Japan Rail Passes, available only to foreign visitors. Sold for seven, fourteen, or twenty-one continuous days of use on the national rail system as well as certain buses and private railways, these passes provide travelers with the opportunity to experience sites and landscapes across Japan at a fraction of the cost. For example, the cost of a round-trip journey on a high-speed train between Tokyo and Kyoto is nearly the same price as a 7-day pass. As a test for upcoming, global events in the nation such as the 2019 Rugby World Cup and the 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games, Japan Rail is selling passes in Japan at select train stations. Previously, visitors had to use partnering tour companies in their home nations and order their passes before traveling to Japan. If adopted, this new, on-site system, will be just one more way that the railways of Japan have bolstered tourism, dispersing concentrations of foreign visitors in the main cities of Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka to other, smaller sites that are more closely linked to domestic tourism of cultural heritage. As a bit of an ode to the railways of Japan, this month’s blog will focus on the ways that Japan’s trains shaped tourism from historical and contemporary perspectives (Videos 1 and 2).

Figures 1 and 2. Dramatically different views of the Hida Historical Village and the Takayama Jinya captured in late February and, again, in late April. The sites were originally discussed in my first research blog post on Japan, found here.

Video 1. Scenes from the train traveling between the castle towns of Nagahama and Hikone in the Shiga Prefecture, east of Lake Biwa.

Video 2. Scenes from the train traveling between Nagoya in the Aichi Prefecture and Takayama in the Gifu Prefecture. The Wide View Hida lines have oversized windows to view the gorges and rapids around the Mashitagawa River and the Nihone Rhine. A view of portions of the landscape in the winter can be found here.

Navigating Cultural Capital

Much of the available literature on tourism in Japan focuses on either travel within Japan during the Edo Period or on anthropological and geographical studies of Japanese citizens abroad.2 The former, however, provides some valuable insights on current tourism patterns in Japan, especially in Central Honshu. During the Edo period, daimyo and their associated traveling parties, ranging from 150 to 2,500 members, spent nearly half of each year commuting between their territories and Edo to pay tribute to the Shogun. Because of the expense of such journeys, this practice helped the Shogun retain physical and financial control of the daimyo but it also cultivated tourism industries for the nearly 250 traveling parties that entered Edo each year.3 For example, the Yoshiwara entertainment district in Edo grew and monzen machi [temple towns] were established to accommodate traveling parties who made cultural pilgrimages to sites like Ise, Kyoto, and Nara (Figures 3–7). In 1899 when the Tokyo Teacher Training School (now the Tokyo College of Education within Tsukuba University) took its first recorded study tour, the future teachers followed the path of Edo era travelers and visited Ise, Kyoto, and Nara.4

Figures 3 and 4. The main street in the ‘temple town’ of Ise still resembles its pre-Edo roots and is lined with sake breweries and fishmongers. In the 18th century the town was home to more than 600 inns but today the majority of visitors take trains and charter buses from Nagoya and Osaka.

Figures 5–7. Photography is prohibited at the Grande Shrine so this creates a more tranquil, observant atmosphere and provides a break from the exercise of dodging selfi-sticks that is commonplace at other temples around the nation. Here it is possible to closely examine the intricate joinery and gilding of the buildings in parallel with the attention paid to the natural elements of the site. For example, bamboo straps protect the base of impressively large cedars from inadvertent damages by passing pilgrims.

With this history of Edo era tourism in mind, it is easier to understand why these sites have been domestic tourist destinations as well as key sites for understanding vernacular architecture. While the capital and port cities were rapidly changing during the industrial revolution, cities like Nara and Kyoto served as prime examples for the reflective study of traditional design and construction: between 1889 and 1891, Imperial University’s first Japanese architecture instructor led his students in an extensive survey and measured drawing project for thirty-eight temples in Kyoto and Nara (Figures 8–10).5

Figures 8–10. Famous for its sacred deer that bow to visitors, especially when being bribed with special cookies sold on-site, Nara is home to dozens of Buddhist temples. Standing in front of the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Todai-ji (12th century), it is hard to fathom that although it is the largest wooden building in the world, the current configuration of Todai-ji is smaller than the first structure that stood on the site between 760 and 1180. With a system of stacked beams and brackets, the inner sanctuary of Daibutsuden [Great Buddha] is from the early 18th century.

Since the late 19th century, railroads have also been at the heart of Japan's tourism industry to sites such as Kyoto. In consultation with engineers from the West, the first railroad in Japan was completed in May 1872, connecting the port of Yokohamma with Shinbashi, Tokyo to the north.6 A few years later, Kobe, Kyoto, and Osaka were connected. In 1893 the Welcome Society of Japan was founded to enhance foreign tourism in the nation, at that time only around 10,000 visitors traveled to Japan a year.7 The group produced guidebooks and posters, marketing accessible sites and cultural highlights. Although there is a complicated history with respect to the nationalization and privatization of railways in the early 20th century it is crucial to note that the rail systems and tourist industry have maintained a dependent and largely beneficial relationship for both domestic and foreign tourists. These early transportation connections, however, may also be credited for what art historian Chelsea Foxwell calls ”self-museumification” and today Kyoto is home to seventeen UNESCO World Heritage Sites.8

Kyoto, perhaps, is the best example of a city where certain areas underwent successive redevelopment and others were preserved but at the cost of commodification (Figures 11 and 12). It is an overwhelming city of cultural and architectural contrasts (Figure 13). Despite my research on Kyoto, my subconscious still expected to find a city filled with tightly packed, low-rise buildings. These layered, wooden buildings would hold hidden gardens and the city's skyline would be anchored by the shadows of the region's surrounding mountains. Although one can find streets filled with traditional buildings and gardens that occupy the foothills of the Kyoto Prefecture, using views of Mount Atago, Hiei, and Kurama as 'borrowed' landscapes, the number of skyscrapers and monolithic residential towers is daunting. The brightly lit blocks lined with high-end retailers, commercial chains, and dense shopping arcades are portions of modern Kyoto that rarely appear in guidebooks or popular images advertised in travel magazines or posters in Japan’s own railway stations. Instead, one can find photographs of the narrow Nishiki Market, filled with an array of stalls and home to Kyoto's seafood sellers for more than 800 years. Shoe stores, cafes, pharmacies, and souvenir shops now crowd portions of the labyrinthine market but, with the help of a local, it is still possible to find historic retailers, offering everything from traditional sweets like seaweed candy to fans and hand-pressed stationary.

Figure 11. The pop-up Hermès Gion-mise concept store by Koichiro Oniki, scheduled for operation for only nine months, within a traditional machiya [townhouse] along Hanamikoji in Gion, Kyoto.

Figure 12. A geisha negotiating the pedestrian and car traffic along Hanamikoji in Gion, Kyoto on her way to the famous Ichirki Chaya teahouse.

Figure 13. A rockabilly group dances in front of the imposing Kyoto City Hall (1927), by Goiichi Murata, on a warm Sunday afternoon.

Somewhat ironically, Kyoto is home to the largest railway museum in the nation yet, internally, it is a city that relies on buses for its public transportation to sites like the Golden Temple, the meditative rock garden of Ryoan-ji, or Ando’s Garden of Fine Arts. Opened in 2016, the Kyoto Railway Museum is highly interactive in reference the exhibits, the inclusion of fifty-three historic trains in the covered plaza and working turntable, and the visitors' connection with contemporary railways since the building's roof terrace overlooks the bustle of Kyoto Station (Figure 13). The new museum replaced the Umekoji Steam Locomotive Museum, housed in the old Nijo Station, and absorbed collections from the Modern Transportation Museum, once located in Osaka. Although much of the museum occupies a new structure, designed by Tohata Architects & Engineers, the project was part of a larger revitalization initiative for an underdeveloped part of town, once a freight yard, that the city has been transforming through recreation and tourism endeavors since the mid-1990s. Bordering an elementary school, Umekoji Park opened in 1995 and was later populated with several of Kyoto’s preserved trolley cars-cum-souvenir shops. Amid animal rights and public access controversies, the Kyoto Aquarium (2012) by Tokyo Architects and Engineers opened on the north edge of the park and despite initial protests, the combination of the park, aquarium, and railway museum have created an active and successful 'edu-tainment' region for school-aged children. Craft fairs and pick-up soccer games occupy the park on the weekends, activating this playful oasis adjacent to one of Japan's busiest railway terminals.

Figure 14. A view from the Sky Terrace of the Kyoto Railway Museum of a Tokaido Shikansen “bullet” train heading southwest to Osaka, with modern Kyoto and the pagoda of Toji (c.796) in the background.

Surrounded by trees and historic trains, the Kyoto Railway Museum feels like a world unto itself within the city and in many ways this replicates the experience of visiting other destinations in and around Kyoto (Figures 15–25). There are quick transitions from densely packed urban areas to pristine, contemplative gardens and sacred sites. However, there are other areas that are so inundated with visitors in the busy spring season that it is difficult to fully comprehend the historic or environmental contexts. Tourists are glued to their smartphones, navigating to parks with apps tracking the peak cherry blossom blooms in area and on a sunny April day the Nijo-jo Castle becomes engulfed in another, modern moat: a sea of charter buses.

Figure 15. A view across the reflecting pond to Kinkaku-ji, the Golden Pavilion. Originally constructed in the late 14th century, the current structure is a replica from 1955, built after a devastating act of arson in 1950 by a deranged monk.

Figure 15. A view across the reflecting pond to Kinkaku-ji, the Golden Pavilion. Originally constructed in the late 14th century, the current structure is a replica from 1955, built after a devastating act of arson in 1950 by a deranged monk.

Figure 16. A gardener painstakingly removes leaves from the moss of the Silver Pavilion’s gardens. Recent restoration work revealed that the building was once covered in colorfully painted tortoise shell patterns, like Kiyomizudera, but it seems unlikely that the paint brushes will touch the pure, muted forms of the Silver Pavilion anytime soon since the small, recreated fragment of the building’s coloration is hidden behind the gift shop and tea room.

Figures 17 and 18. The view from the “Pure Water Temple” of Kiyomizudera (b.780) are some of the best in Kyoto and the site is currently undergoing a massive roofing renovation project and is covered in an elaborate system of bamboo scaffolding. However, the recent restoration of other shrines and pagodas in the complex present viewers with vibrant painted architecture

Figure 19. There are two different routes to Kiyomizudera: one through a terraced, sprawling cemetery and another along the steep Higashiyama District, a series of streets crowed with tourists ad stalls selling macha, django (sweet dumplings made from rice flour) and souvenirs.

Figures 20-22. Although much less popular than the adjacent botanical gardens, Ando’s Garden of Fine Arts (1994) provides an interesting juxtaposition of water, sloping concrete forms, and recreated artworks, presented at the same scale as the originals. Through ramps, plateaus, and promontories, Ando allows visitors to make closer inspections of the famous works and see them in an open-air context; with the exception of Monet’s Water Lilies- Morning that is submerged in a floating, concrete pool.

Figures 23 and 24. Identified as an unparalleled example of Hein architecture and located southeast of Kyoto, Byōdō-in (1053) consists of gardens and the Phoenix Hall, housing the large, wooden Amida Buddha. Intricately carved Unchu Kuyo Bosatsu surround the Buddha but almost half the original fifty-two figures in the hall have been relocated to the on-site Temple Museum (2001), designed by Akira Kuryū (b. 1947). Through the use of topographic and material changes, the site manages to effectively unite historic and contemporary architecture: the new building is partially subterranean Temple Museum (2001) and its board-formed concrete walls and wooden screens provide a darkened atmosphere for inspecting preserved wooden sculptures and bronze casts from the site. Here, and at several other historic and sites and galleries around the nation, posted signs prohibit sketching. In certain gardens and buildings this seems logical: pathways are too narrow and can be crowded so sketchers would impede the flow of traffic. However, at sites like Byōdō-in the rules discouraging sketching, even in pencil, seem curious and almost arbitrary since photographs are permitted throughout all of the site but the Buddha Hall.

Figures 25–27. The massive complex of the Kyoto International Conference Center (b. 1963) by Sachio Otani can hold 7,000 conference participants, with more than seventy conference rooms spread between the main building, the annex and the event hall. Otani won an open competition for the site along Lake Taragaike and created a reinforced concrete mega structure, with adjacent gardens and paths that feel like floating engawa, extending the building further into the expansive landscape. With a plan focused on circulation for large groups of people, open stairways, stacked lobbies, and wide hallways create spaces for serendipitous meetings and discussions. The main conference hall housed the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change that resulted in the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 and guided visits of the complex can be arranged online.

A Town Reassembled by Train: Meiji-mura

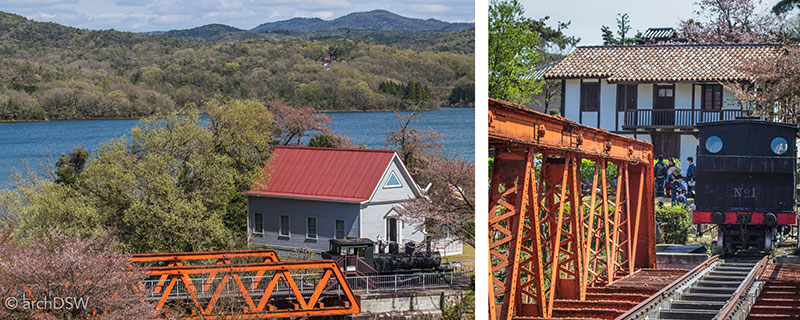

Traveling north of Kyoto to Japan's largest train station at Nagoya, connected to a 13-story shopping mall, it is possible to take a bus or regional train to Inuyama to visit one of the most extraordinary, and possibly overlooked, architectural sites in Japan: Meiji-mura. Similar to the Hokkaido Historical Village in Sapporo, the Hida Folk Village in Takayama, and the Edo-Tokyo Open-Air Architectural Museum west of the capital, Meiji-mura is an ‘architectural theme park’ that is catered to domestic tourism more than foreign visitors. In the spring, teenagers on school trips fill the site in their distinguishing uniforms, taking selfies with costumed interpreters and running between the food vendors and various exhibits installed in the sixty-eight historic structures, listed here with the exception of the most recent structure added in 2007. Divided into five areas, the park occupies nearly 250 acres around Iruka-ike Lake, a reservoir 16km in circumference. The park is so expansive that it offers (for a fee) three modes of historic transport: an imported steam locomotive (1874) from England, a streetcar from the Fushimi Line of the Kyoto electric Railway, and a ‘village’ bus.

There is little scholarly work published in English about the park, but landscape architect Susan Herrigton’s article provides a useful way of reading the open-air museum as a site, like other parts of ‘museumified’ Japan, that exists out of place and time.9 On the eve of the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo, the first year in Japan’s history that would record more inbound than outbound tourism, architect Yoshiro Taniguichi (1904–1979) recognized that much of Tokyo’s historic fabric from the Meiji Period (1868–1912) would be destroyed to modernize the capital. Soliciting the financial and logistical aid of a childhood friend and railroad baron, Moto-o Tsuchikawa (1903–1974), Taniguichi founded Meiji-mura as a site for the relocation and preservation of significant structures that would have otherwise met the demolition crane. With fourteen buildings, the park opened on March 18, 1965.10

Structures were added on a yearly basis between 1965 and 1990, with relocation and reconstruction costs often covered by partnerships with Japan National Railways. Over the course of its development, the park became a place to study the formal characteristics associated with western architectural influence, but the buildings are treated as objects within the landscape and have little interpretation on their typology, functional aspects, or construction methods. The signage around the open-air museum focuses on relaying key dates, explaining the roles of relevant historical figures, and displaying a plan for each building. Therefore, the park and its architectural artifacts form a picturesque garden composition (Figure 28). A visitor rarely approaches a building in a straightforward manner and is, instead, rewarded with an on-axis view only after walking around the building. There are unexpected turns in pathways and framed views as well as moments encapsulating the Japanese garden concept of meigakure [hide and reveal] (Figure 29).

Figure 28. A view of Area 5, with two bridges, the Cabinet Library (1911) from Tokyo, and a fragment of the Head Office of the Tokyo’s Kawasaki Bank (1927)

Figure 29. A portion of the Mie Prefectural Normal School (1888) was relocated to the site but now provides a framed view of the landscape instead of the surrounding town of Kuramochi Nabari.

The large area of land reserved for the park at its inception allowed for a ‘suburban’ approach to building placement in the 1960s and 1970s but as more structures were added, the fabricated village began to infill the spacious plots (Figure 30).11 The park’s name also became a misnomer: structures were added from the Taisho (1912–1926) and Shōwa (1926–1989) eras. This evolution created what, at first glance, appears to be an architectural hodgepodge of building types and materials but it actually puts disparate styles and forms in conversation, illustrating advancements in building, practical sciences, and engineering. The number of schools at the park underscores the value of education in diverse settings, from rural and urban contexts to specialized structures for students with special needs: there is a high school physics and chemistry theater (1890) from Kanazawa’s Fourth National High School, the auditorium of the Chihaya-Akasaka’s Primary School (1897), and the entry porch to the main building of the Tokyo School for the Blind (1910). Factories highlight the rise in industrial production and several of the objects of infrastructure highlight mass production and the needs of a growing nation (Figures 31–33). The relocated churches in the park illustrate the different architectural styles that could be associated with Christianity, a religion practiced by only about 1% of the nation’s population (Figures 34–40).

Figure 30. A view over the ‘urbanized’ composition of Area 2.

Figure 31. The Rokugogawa Iron Bridge (1909) is thought to be oldest in the nation and it spans a portion of Area 4 while supporting a static display of a steam locomotive (1897) imported from the United States for the Bisai Railway.

Figure 32. The Tokyo Central Station Police Box (1914) is a ferro-concrete structure that once housed twelve police officers, ready to assist with the frequent visits between foreign dignitaries and the Emperor.

Figure 33. Seen from the light keeper’s house of Sugashima Lighthouse (1873), the Shinagawa Lighthouse (1870) from Tokyo is the oldest in the nation and shows how the park melds buildings from different places into paired compositions.

Figures 34 and 35. The Uji-yamada Post Office (1909) is still in active operation, allowing visitors to send postcards and letters from within the Meiji-mura complex. The public was relegated to a small area of the building, naturally lit by the conical dome floating above a drum of clerestory windows, and an open, factory-inspired plan throughout the rest of the structure facilitated expedited work.

Figures 36 and 37. St. John’s Anglican Church (1907) from Kyoto, a Western structural system mixed with Japanese carpentry traditions: the windows used intricate wooden joinery and the groin vaults integrated bamboo.

Figures 38 and 39. The Neo-Gothic cathedral of St. Francis Xavier’s (1890) was originally located in Kyoto and the experimental use of double paned, colored glass creates a vibrant interior in afternoon light.

Figure 40. St. Paul Daimoji Church (1879) was originally located in the center of Japan’s Christian population in Nagasaki and like many other structures on the site, it raises more nuanced questions about the building’s architectural history: nearly twenty years passed between the dismantling of master craftsman Isekichi Ohwatari’s church and the building’s relocation to the park in 1994.

Unlike other open-air architectural museums in the nation, Meiji-mura has several buildings from abroad and others that showcase developments in environmental manipulation (Figure 41). However, these are stories largely untold at the park and leave visitors without ways of understanding the social or performative factors that shaped the built environment. Although the buildings at Meiji-mura are divorced from their original sites, the Oguma Photography Studio (1908) from Nigata Prefecture illustrates an important level of attentiveness to building orientation: the skylights on the studio's upper floor originally faced north, providing beneficial levels of diffused daylight in an era before the widespread integration of artificial lighting, and this cardinal orientation was retained when the building was relocated to the park (Figures 42 and 43).

Figures 41. The Evangelical Church and pastor’s house (1907) from Seattle, Washington was originally constructed by an American family but later used by Japanese immigrants. Other foreign properties in the park include the Japanese Immigrant’s Assembly Hall (1889) from Hilo, Hawaii and a Japanese Immigrant’s House (1919) from Registro, San Paulo, Brazil.

Figures 42 and 43. The Oguma Photography Studio was located in Honmachi Jyoetsu in Niigata Prefecture. The building's skylights are not oriented true north but, instead, to the northeast. The configuration is matched at the Photography Studio of Hirose (1924) that is preserved at the Hokkaido Historical Village in Sapporo. It is possible that this orientation provided the studio more optimal morning light and the drying room, located on the southwestern side of both home, longer periods radiant heat. Unfortunately, few of the buildings at Meiji-mura or other open-air architectural museums explore building typologies, materials, or functionality in much depth so the structures become occupiable objects than can only be decoded with additional research and analysis off-site.

Sites like Meiji-mura raise interesting questions with reference to foreign tourism and sustainable operations. The site is not easily discovered, making it a very purposeful destination and based on my visit and research, the three main groups that the site receives to are Japanese schoolchildren, architectural enthusiasts, and film crews. Many of the structures are now approaching an age where they have been at Meiji-mura longer than they were on their original sites, so how will the park deal with critical questions of preservation? Although filled with more sites than can be thoughtfully covered in one day, there is available space and it will be interesting to see if the park continues to add structures that expand the definition of ‘historic’ into the later Showa (1926–1989) or Heisei (1989–present) periods. There are fewer plans for sweeping overhauls of historic buildings in conjunction with the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo but there is clearly a culture of impermanence associated with post-war buildings in the capital: could portions of the charred Nakagin Capsule Tower (1972) be relocated to Meiji-mura or will from façades from Tokyo’s haute couture areas in Ginza or Omotesando eventually occupy the hills of the park? As mentioned in last month’s blog post, notable contemporary structures like Ando’s Rokko Chapel are falling into disrepair so a new home in an open-air museum could be inline with Japan’s approach to the curation of architecture, if there are champions for the preservation of modern buildings.

To conclude, below are a few images of Meiji-mura’s most famous building and arguably the reason why so many foreigners make the trip to the site: a portion of the lobby and reflecting pool of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel in Tokyo (1923–1968). Wright’s trips to Japan began in 1905, driven by his interest in Japanese prints and desire to supplement his waning architectural income by serving as an art dealer.12 It is estimated that he spent more than $500,000 on prints, noting that Japanese ukiyo-e were, "one of the most amazing products of the world, and I think no nation has anything to compare with it."13 With an established appreciation of Japanese art and culture, he was recommended for the task of designing a new Imperial Hotel that would be, “a building that would be an object lesson to Japanese and Europeans and Americans alike."14

Kathryn’s Smith’s article “Frank Lloyd Wright and the Imperial Hotel: a Postscript” comprehensively outlines the struggles following the commission and Wright’s six trips to Japan between 1916 and 1923, riddled with illness, art forgery scandals, fires, and the Great Kantō earthquake that rattled, but did not destroy, the hotel on its opening day of September 1, 1923. The stability of the building, credited to its steel frame and reinforced ferro-concrete, and its use as an unofficial center for relief and recovery contributed to Wright’s architectural and structural hubris, and even landed him a place in Who’s Who in America.15 With the Imperial Hotel, Wrieto-San, as he was known in Japan, had achieved international architectural fame.

The three-story hospitality masterpiece, with its courtyards, cast concrete ornaments, and reinterpretation of Japanese lanterns using carved Ohya turf stone and terra cotta blocks, was dismantled in 1968 to make way for a new, high-rise hotel but thankfully portions of the building made their way to Meiji-mura for preservation. Today, the building has an active café and small shop, with carefully placed curtains that suspend the illusion that the structure is little more than a fragment of its original incarnation. The reproduction chairs and tables make the lobby a welcoming space to rest and observe the intricacies of the interior, imagining the times when stars like Marilyn Monroe and Charlie Chaplin were guests.

Today, Wright’s Imperial Hotel is frequently used as a set for photography and film projects. On the day of my visit, the lobby was a backdrop for a few elaborately dressed ‘vampire geisha’ but it has been used for period pieces and Japanese dramas. Hopefully, some of these projects are revenue generating for the park since a substantial restoration and preservation project cannot be too distant for this building with visible signs of water damage and friable stone.

For those interested in more on the building, a range of postcards and printed ephemera can be found on the Imperial Hotel page of the Wright Library and those in Chicago can actually see the only known piece of the building on exhibit outside of Japan: a lantern fragment in the Architecture and Design Gallery of the Art Institute of Chicago.16

Figure 44. An aerial view of the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, c. 1935–1940. Image from Film and Digital Times.

Figures 45–47. The exterior of Wright’s Imperial Hotel at Meiji-mura.

Figure 48. A postcard showing the interior of the Imperial Hotel in the 1930s.

Figures 49-52. The interior of Wright’s Imperial Hotel at Meiji-mura.

Bibliography

Foxwell, Chelsea. "Japan as Museum? Encapsulating Change and Loss in Late-Nineteenth-Century Japan." Getty Research Journal, 1 (2009): 39-52.

Funck, Carolin, and Malcolm Cooper, eds. Japanese Tourism: Spaces, Places and Structures. 1 ed. New York, NY: Berghahn, 2013.

Herrington, Susan. "Meiji-Mura, Japan: Negotiating Time, Politics, and Location." Landscape research. 33, no. 4 (2008): 407-23.

March, Roger. "How Japan Solicited the West: The First Hundred Years of Modern Japanese Tourism." Paper presented at the 17th Annual CAUTHE: Tourism-Past Achievements, Future Challenges, Sydney, 2007.

Meech, Julia. Frank Lloyd Wright and the Art of Japan: The Architect's Other Passion. New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, 2001.

Meech-Pekarik, Julia. "Frank Lloyd Wright and Japanese Prints." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 40, no. 2 (1982): 49-56.

Nakagawa, Koichi. "Prewar Tourism Promotion by Japanese Government Railways." Japanese Railway & Transportation Review 15 (March 1998): 22-27.

Nute, Kevin. Frank Lloyd Wright and Japan: The Role of Traditional Japanese Art and Architecture in the Work of Frank Lloyd Wright. London: Chapman & Hall, 1993.

Smith, Kathryn. "Frank Lloyd Wright and the Imperial Hotel: A Postscript." The Art Bulletin 67, no. 2 (1985): 296-310.

Suzuki, Akira. "Gaikoku Mura: Photogenic Tourism for Hypertourists." AA Files, no. 48 (2002): 33-38.

Wendelken, Cherie. "The Tectonics of Japanese Style: Architect and Carpenter in the Late Meiji Period." Art Journal 55, no. 3 (1996): 28-37.

Zukowsky, John. "Section of a Lobby Lantern from the Imperial Hotel, Tokyo." Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 30, no. 1 (2004): 26-94.

1 The Japanese celebration of Buddha’s birthday does not align with the Buddhist calendar.

2 Carolin Funck and Malcolm Cooper, eds., Japanese Tourism: Spaces, Places and Structures, 1 ed. (New York, NY: Berghahn, 2013), 5.

3 Ibid., 21.

4 Akira Suzuki, "Gaikoku Mura: Photogenic Tourism for Hypertourists," AA Files, no. 48 (2002): 48.

5 Cherie Wendelken, "The Tectonics of Japanese Style: Architect and Carpenter in the Late Meiji Period," Art Journal 55, no. 3 (1996): 30-32.

6 For the best history on this topic see Roger March, "How Japan Solicited the West: The First Hundred Years of Modern Japanese Tourism" (paper presented at the 17th Annual CAUTHE: Tourism-Past Achievements, Future Challenges, Sydney, 2007).

7 Koichi Nakagawa, "Prewar Tourism Promotion by Japanese Government Railways," Japanese Railway & Transportation Review 15 (March 1998): 22.

8 Chelsea Foxwell, "Japan as Museum? Encapsulating Change and Loss in Late-Nineteenth-Century Japan," Getty Research Journal, 1 (2009): 40.

9 Susan Herrington, "Meiji-Mura, Japan: Negotiating Time, Politics, and Location," Landscape research. 33, no. 4 (2008).

10 Ibid., 408.

11 Ibid., 408-09.

12 For more on Wright’s fascinating, and problematic, career as a Japanese print importer and dealer see Julia Meech, Frank Lloyd Wright and the Art of Japan: The Architect's Other Passion (New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, 2001); Julia Meech-Pekarik, "Frank Lloyd Wright and Japanese Prints," The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 40, no. 2 (1982); Kevin Nute, Frank Lloyd Wright and Japan: The Role of Traditional Japanese Art and Architecture in the Work of Frank Lloyd Wright (London: Chapman & Hall, 1993).

13 Meech-Pekarik, 56.

14 Kathryn Smith, "Frank Lloyd Wright and the Imperial Hotel: A Postscript," The Art Bulletin 67, no. 2 (1985): 297, n. 8.

15 Ibid., 310.

16 John Zukowsky, "Section of a Lobby Lantern from the Imperial Hotel, Tokyo," Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 30, no. 1 (2004).

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top