-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Medieval Masons and Gothic Cathedrals

Deyemi Akande is the 2016 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

There is an old legend that suggests that the striking design of the Cologne Cathedral was in fact given to Master Gerhard of Ryle by the devil.1 Even the ability to build the impossible structure was ascribed to the same source. In fairness to this fable, the size and magnificence of the Cologne Cathedral is worthy of otherworldly credits and it makes good sense that a fantastic legend such as this is the only way Middle Age Cologne could explain this incredible structure taking shape before their eyes. A fantastic cathedral however, no devil builds! This cathedral, as all others we know and have come to adore, is a result of the tireless and brilliant coordination of the rare and inestimable gifts of men we know as masons.

I am now in Germany, the land of the Rhine, the pride of the early Goths, and a place of many remarkable cathedrals. Almost everywhere you turn, you are confronted by one towering spire or the other. And every one of these masterpieces has its own unique story. In the center of the story, always, is a master mason; the architect of the impossible, a gifted and cerebral one, a craftsman who knows his trade too well. One other thing the master mason knows too well, is that more times than naught, he is only there to initiate the ‘miracle’ and almost never sees the work in completion. Many cathedrals take too long to finish and to be a master mason in the first place, you must have invested your years. In spite of this, many masons still maintained a type of dedication we may hope for now only in theory. What makes the mason so exceptional in thought? Why, in spite of the odds, are they so meticulous? What did building a cathedral mean to the mason for them to give sweat and blood to it even in low pay and less than ideal construction conditions? We know now against popular notions that many were not even men of the faith—such that we could argue that they do it in reverence and worship to God. Yet, they offer their skills with the highest conduct exalting royalty—both heavenly and earthly in the most astounding figural and architectural display that men may ever know. Why?

Figure 1: A painting by artist and German architect Vincenz Statz, 1861. ‘And it Will Be Completed,’ the vision of the finished Cologne Cathedral in watercolor.

Figure 2: Chisel and mallet in hand, the lone mason, brilliant craftsman and a gift to humanity. This stone representation of a mason hard at work was found in front of the Mason’s lodge at the east end of Cologne Cathedral.

Figure 3: Stone statue on masonry: A clear example of the beauty and intricacy of a mason’s work.

Figure 4: Statue of Saint Peter in the south-eastern end of the Cologne cathedral.

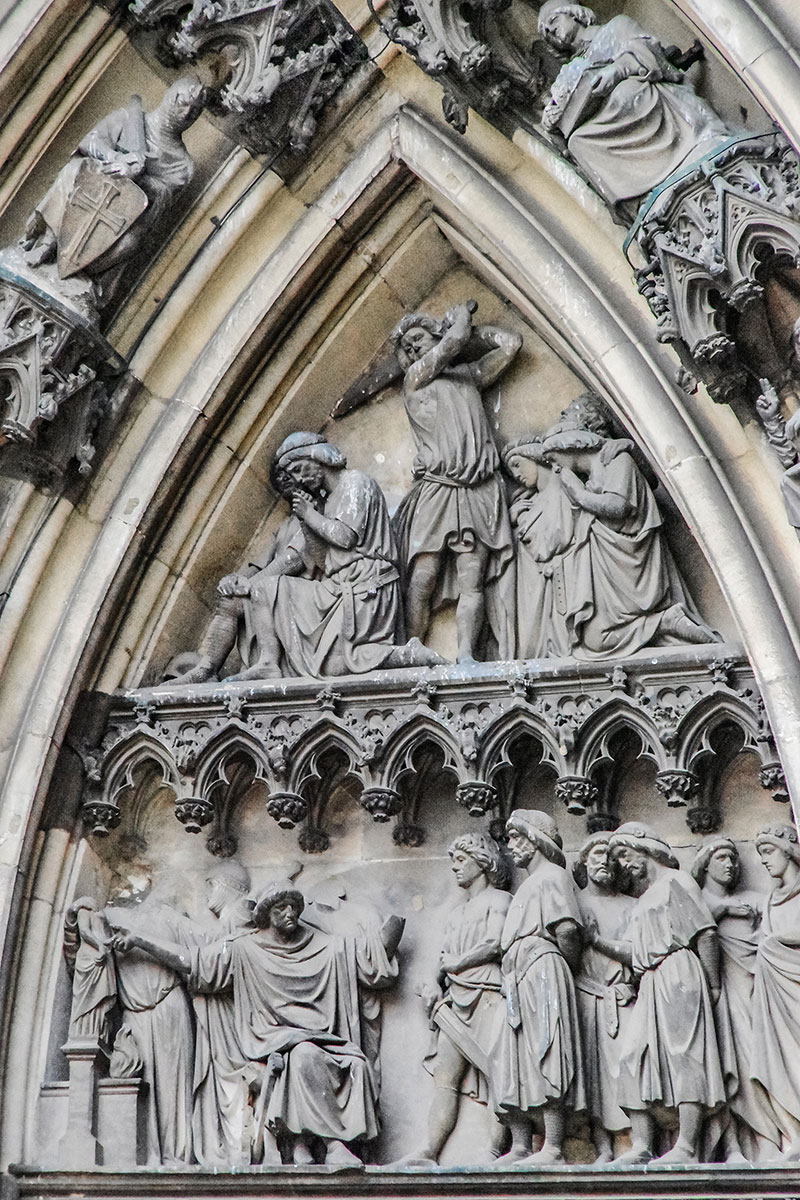

Figure 5: The mason’s work exalting earthly kings.

Figure 6: Carved capital at the Magdeburg cathedral.

Figure 7: Details of the cathedral tower in Frankfurt. A clear example of the beauty and intricacy of a mason’s work.

I have asked why, just so perhaps we may be able to learn something from their art of dedication. Let us look a little at the nature of the mason’s craft. If we called them the illusionists of the medieval era, we may not be faulted—for one can safely refer to most of the art and structures created by the medieval mason as nothing short of illusory magic on account of their seeming improbability. Cragoe in the article The Medieval Stonemason asserts that they were not monks but highly skilled craftsmen who combined the roles of architect, builder, craftsman, designer, and engineer.2 Many, if not all masons of the Middle Ages learnt their craft through an informal apprentice system. They would generally be members of a guild comprised of different artistic styles and varying skill levels. There were three main classes of stonemasons. They were the apprentice, journeymen and the master mason. At a cathedral construction site, the master mason is usually the head and he oversees the work of all skilled and unskilled laborers. His army of workmen will include carpenters, layers, metal-smiths, carriers, rope makers, and even occasionally animals—oxen. What the medieval mason lacked in technology, he made up for it in ingenuity and personal skill. The combination and coordination of their collective skills are what gave us the architectural miracle we see today.

The work is a long, hard, and mostly dangerous one. More times than we wish to admit, many of the master masons—though they died old, they didn’t die of old age—a number were in fact killed or fatally injured at or by the very cathedral they dedicated themselves to build. Master mason Gerhard of Ryle who was the first master and key brain behind the Cologne Cathedral fell from the scaffolding of the cathedral in April 1271 and died.3 There is the debate that Gerhard fell under mysterious circumstance. This has fed well into the myth of his purported deal with the devil for the design of the cathedral. Gerhard was not as lucky as William of Sens who also had the same accident but survived. At Canterbury Cathedral in 1178, master mason William of Sens also fell from the scaffolding during his inspection of the high vaults and was paralyzed.4 Countless of other cathedral site workers have either fallen to their death or been crushed by collapsing portions of the edifice.

Figure 8: Ornate cross-like form on the tip of one of the pediments on Cologne cathedral, a clear example of the beauty and intricacy of a mason’s work.

Figure 9: One of the statues on the Western portals of Cologne Cathedral. A shepherd and his sheep.

Figure 10: Monstrous in size, coloured by age, it stands regal and stately. The towers of the Cologne Cathedral.

Figure 11: A miniature size installation showing a typical medieval construction site. An insight into the life and work environment of medieval masons.

Some notions will suggest that the dedication of masons can be related directly to the amount of money paid them. They argue that the church would often put a huge sum of money into building construction and this served as good incentives for the masons and other construction workers. It appears generally sensible, but I fear it may not be totally accurate. Though the church would be raking in quite a sum through the sales of indulgence and the exhibitions of relics, we know that the economics and financial management of cathedral construction is anything but seamless and structured. Besides, through the years the need for skilled masons fluctuated depending on the times and the finances available. There have been instances, particularly in Norman areas around the 11th century, when farm workers would sometimes be on hand to work at church construction sites as semi-skilled labor for free. This may have undermined—to some extent—the overall value attached to the work of members of the mason’s guild.5 Mostly after the fall of the Roman Empire, there was a decline in the use of stone in much of Western Europe as timber became more favored. Masonry, however, came back to the fore from around the 10th century and by the 11th–12th centuries, the re-emergence of stone as a key building material had reached a new peak with religious buildings.

To what then will one ascribe the exceptionality of the medieval mason? I have sat in contemplation of this for a while and seem not to have a reasonable answer as yet. When you have the opportunity to examine the mason’s work on Gothic cathedrals around Europe, you will indeed be forced to pause and ask questions. Perhaps being born of this era, I am unable to, or incapable of making sense of the opulent nature of the medieval mason’s work particularly when viewed in context of aspects like the economics, functionality, and other factors that color modern understanding of reasonability. What I am capable of, however, is to see clearly, that after 800 years (and in some cases, more) these great cathedrals are still in use for their original purpose and in comparison to castles, pyramids or any other massive stone structure of the early ages, cathedrals stand a step ahead of others. If this is not reasonable, then I am at a loss for what is.

Figure 12: The blending of materials—a giant oak sculpture of St Michael gracefully hangs on the stone pillars in the nave of the Cologne Cathedral. The statue was made by Georg Grasegger in 1919 to commemorate the dead of the First World War.

Figure 13: One of the fine floor mosaic pieces in the ambulatory of the Cologne Cathedral. In the center is a model of the great cathedral itself.

Figure 14: Richly decorated ambulatory floor. The very vibrant colour of the mosaic adds life to the passageways.

Figure 15: The isle of the southern end showing impressive vaulting.

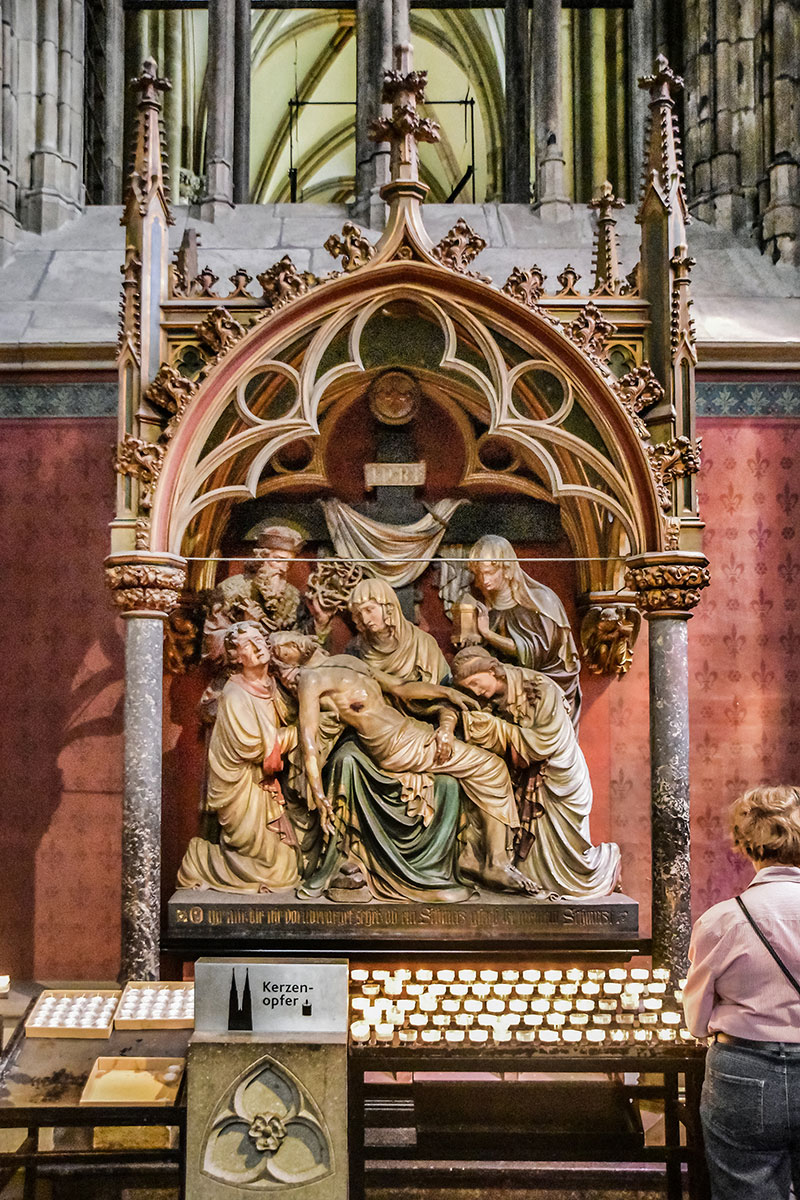

Figure 16: Pietà—an altar piece of one of the shrines in the Cologne Cathedral.

Figure 17: The Cologne Cathedral showing the two western towers and part of the southern façade.

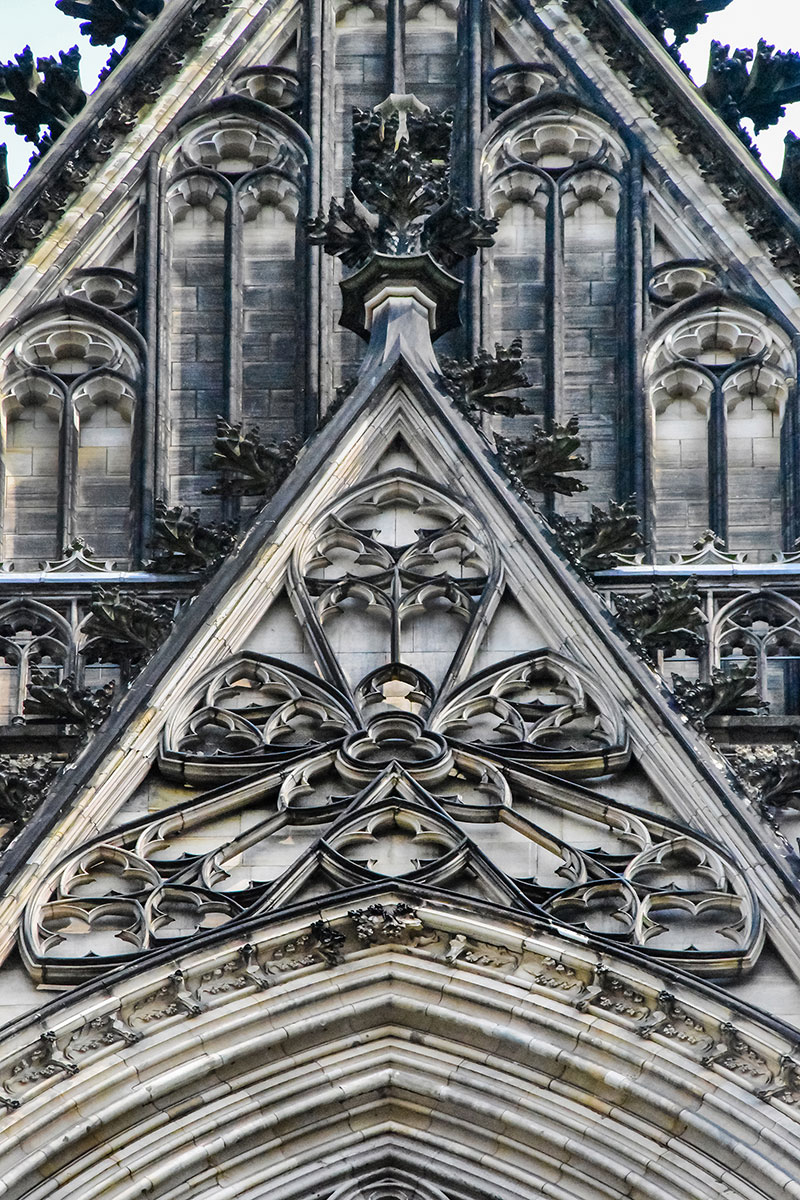

Figure 18: Close up of masonry details on the western façade.

Figure 19: Detail of the hand of one of the sculptures on the western facade of Cologne cathedral. The hand holds an axe in one hand and a book (Bible?) in the other. The axe has a cross quite visibly engraved on it.

Figure 20: A sculpture celebrates a sculptor (or perhaps all men who work with and shape stone) at work.

Clearly, sometimes questions are answered and other times they are not. In this case, the later seems to be my fate. The whys that I have raised in the early part of this article may have to linger a while longer as I am yet unable to proffer answers to them. In all I have seen, however, there is evidently something unique about the masons of medieval times. It is unclear to me if the key to their dedication is in the reality of their time. I presume it best to leave that for all to ponder further on. Suffice to say though that such dedication to a craft, such nobility, and perhaps such patience and order will continue to be rare even now and the near future. The arguments for and against this position obviously will be for another time.

Figure 21: Western façade of the Cathedral of Saints Catherine and Maurice, also known as Magdeburg Cathedral.

Figure 22: Details of a portion of the western façade of Magdeburg Cathedral.

Figure 23: Details of the pinnacle of one of the towers of Magdeburg Cathedral.

Figure 24: Statues atop the western façade of the Magdeburg Cathedral. At the peak is the Virgin Mary, lower left is St Maurice brandishing the Holy Lance, and lower right is St Catherine.

Figure 25: Ornate capital at the Magdeburg Cathedral courtyard. A fine example still of the creations of medieval stone masons.

Notes on Some Cathedrals—Cologne, Magdeburg, Frankfurt

Even by today’s standards, the size (height) of Cologne Cathedral is imposing to say the least. Like many cathedrals I have seen in my travels, the current masterpiece sits on the site of an older church or cathedral that has been destroyed by fire. Between April 1246 and November of 1247, the cathedral chapter of Cologne decided to replace the old Carolingian church with a modern one.6 Archbishop Konrad of Hochstaden laid the foundation for the new cathedral on the Ascension of the Virgin Mary in 1248. As mentioned earlier, the first architect of the cathedral was Master Mason Gerhard who is believed to have studied the art of Gothic architecture in France. The story from Gerhard to the second master mason who took over after Gerhard’s demise—Master Arnold—is a long one, but suffice to say that the building was in construction for very many years with intermittent disruptions to construction. The completion of the cathedral, being the largest in Germany, was celebrated as a national event on 14 August 1880, 632 years after construction had begun. As it was told, everyone who mattered was present at the opening ceremonies.

The most distinguished work of art in the cathedral is the Shrine of the Magi, commissioned by the archbishop of Cologne in 1190. This piece takes the shape of a traditional basilica church. It is said to be made of bronze but covered with silver and gemstones. Made by Nicholas of Verdun, it is believed to hold the remains of the Three Wise Men. In 1864, the shrine was opened and it in fact contained bones and garments.

All through the Cologne cathedral there is a deliberate theme of the adoration of the Magi both on stained glass windows, choir stall screen paintings, triptychs, and altarpieces. The setting shows the Three Wise Men visiting baby Jesus and offering gifts. The stained glass pieces were so naturalistic and vibrantly colored—quite a sight to behold.

At Magdeburg, the Cathedral of the Saints Catherine and Maurice also proved a worthy sight to behold. Age shows on this building—but not in a bad way. Age colors it in a way that you can’t but adore it. Here again, the wonders of the work of masons are made apparent. It is a cathedral dedicated to the Saints Catherine and Maurice. Maurice we will recall is famed to be the first black Catholic saint. In the quire of the cathedral, one will find a rather austere but telling statue of Saint Maurice. He is said to be an Egyptian born ca. 250 CE in the Thebes region. A Roman soldier and eventual leader of the all Christian Theban Squadron. After refusing to sacrifice to old Roman gods and repeatedly challenging orders to attack Christian settlements, the Emperor ordered his ranks to be decimated by killing every tenth man in a line up. Despite this, the Theban squadron under the leadership of Maurice is said to be resolved to meet their death rather than go against God’s will. In the end, according to the writings of Eucherius, Bishop of Lyon ca. 450 CE, the emperor ordered all that is left of the 6000 Theban squadron be executed. Martyred for his beliefs, Saint Maurice is today a patron saint to many groups and war veterans. While there is nothing strange about seeing sculptures of saints on Gothic cathedrals in Europe, a black saint is indeed uncommon and noteworthy. Magdeburg Cathedral is said to have 29 sculptural representations of St Maurice on the architecture but probably the most commanding of the presence of a strong-willed general is the piece in Fig. 39.

In Frankfurt as it was in Cologne and Magdeburg, I am faced with the wonderful craft of the mason and how in the many years, it continues to be a beacon and source of inspiration to many. Though the Frankfurt cathedral currently standing is of far newer origins, it nonetheless evokes and animates the exceptional abilities of the stone masons.

Figure 26: The shrine of the Magi. This reliquary sarcophagus is said to hold the remains of the Three Wise Men and it resides in the quire of the Cologne Cathedral.

Figure 27: A fine example of the ‘Bavarian windows.’ Here the theme is the Adoration of the Shepherd and Magi in the middle and the four prophets in the lower levels—Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel.

Figure 28: Stained glass details of the middle pane—showing the Adoration of the Shepherd and Magi.

Figure 29: In closer detail still. And they brought gifts to the Messiah and Saviour.

Figure 30: The fountain of St Peter at the South-eastern end of the Cologne Cathedral.

Figure 31: Masonry and sculptural details on the Cologne Cathedral.

Figure 32: Details of floor mosaic according to the design of August Essenwein 1885–1892.

Figure 33: Details of floor mosaic showing floral patterns according to the design of August Essenwein 1885–1892.

Figure 34: Western Façade of the Magdeburg Cathedral.

Figure 35: Details of masonry and ornamentation on the western façade of the Magdeburg Cathedral.

Figure 36: One of the 29 figural representations of St Maurice on the Magdeburg Cathedral.

Figure 37: Another of the 29 figural representations of St Maurice on the Magdeburg Cathedral. This one is found on the clerestory level just above the quire.

Figure 38: Another of the 29 figural representations of St Maurice on the Magdeburg Cathedral. This is found on the western façade (exterior) of the cathedral.

Figure 39: Probably the most enigmatic of the 29 figural representations of Saint Maurice in the Magdeburg cathedral. Placed directly opposite the statue of Saint Catherine in the Quire of the cathedral, it is a rather austere but telling piece.

Figure 40: A beautiful example of the fluidity of stone in the hands of the mason and sculptors of the early era. This piece is inside the Magdeburg cathedral.

Figure 41: The two towers of the Magdeburg cathedral. Notice the ratio of the car and people to the size of the cathedral.

Figure 42: Western tower of the Frankfurt Cathedral.

Figure 43: The baptismal font inside the Frankfurt Cathedral.

Figure 44: Detail of the font cover.

Figure 45: A lovely rendition of the famous Pieta in the nave of the Frankfurt Cathedral.

Figure 46: Columns and vaulting of the nave of Frankfurt cathedral.

A Small Note on Berlin

Very early in my visit to Germany, I had made it a point to visit the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin, and visit I did. The gate is a must see if you ask me. There is something richly magical about a piece of the ‘old’ made manifest in the new. The gate appears majestic and spirited as ever, surmounted by its iconic quadriga, it wields a type of wisdom that comes with age. As I stand before the monument, I couldn’t help but feel a sense of place and importance, for here where I stand, stood many—commoners and royals alike. Here, the grounds have supported wars and rumors of wars. The trees have witnessed the passing of time like no other can boast. And the architectural monument proudly embodies the vestiges of time itself.

As I soak in the aura of the Brandenburg gate, it suddenly became clear to me that to say I stand before this gate will amount to a compositional error. It will suggest that ‘I’ firmly hold a ground here, but how can we claim any form or grounds in comparison to the gate itself, an unmoving persona that has stayed its ground since 1791? This gate was here when Napoleon in 1806 rode triumphantly on horseback after defeating the Prussians in the battle of Jena-Ausrstedt. It was here, when Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany in 1933 and a huge parade came through its laps. It was here, all during the horrors of the world wars, seeing men, women, and children lack, want, and die. It was here as witness when the Berlin walls kept people and dreams apart. It was also here when President Reagan charged General Secretary Gorbachev to tear down this wall. I would wager that there is a good chance this gate will continue to be here for many years to come—the same, we cannot say for ourselves, mortals. So how then can I suggest that I stand before this great gate? It is the Brandenburg gate that stands, the rest of us are merely passing through.

Figure 47: A painting by Charles Meynier shows Napoleon’s triumphant entry through the Brandenburg Gate in 1806 after the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt. Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 48: Soviet soldiers at the Brandenburg Gate in 1945 during World War II. Photo Credit.

Figure 49: The Quadriga of the Brandenburg Gate

Figure 50: The Brandenburg Gate in 2017.

Figure 51: A view of Frankfurt showing the River Main in the foreground.

Figure 52: A view of Frankfurt showing the River Main.

1 Ruland Wilhelm, Legends of The Rhine; The Cathedral Builder of Cologne, Trans. Mitchell A. and Findlay H. J. (Cologne: Hoursch & Bechstedt, 1906)

2 Cragoe C. Davidson, accessed June 27, 2017, The Medieval Stonemason (2011) http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/middle_ages/architecture_medmason_01.shtml

5 Brooke C. N., The Normans as Cathedral Builders, text of a lecture given in Winchester 1979, The Architectural History of Winchester Cathedral (Winchester: R. Willis 1980)

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top