-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

French Gothic Accent in a Spanish Cathedral

Deyemi Akande is the 2016 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

I’d say my Spanish is horrible, but that would not be an accurate assessment. To say that my Spanish is horrible would suggest that I speak the language. The truth is, other than hola, gracias, and bueno, I do not speak a word more in Spanish. Yet, here I am in Madrid doing rather well communicating with the people around. All thanks to Google on one hand, for its language translation feature, but more significantly, thanks to architecture. I only need to flash a photo of my destination to a passer-by and they always go "Ah, recto (go/continue straight)!" Architecture is a major part of a city’s identity. It gives us a sense of bearing and location. Most likely, it is to architecture we will turn to first when we seek to establish the identity of a place—even in its most basic form of a line drawing or silhouette, architecture stands up to the task of giving a dignified identity to a place.

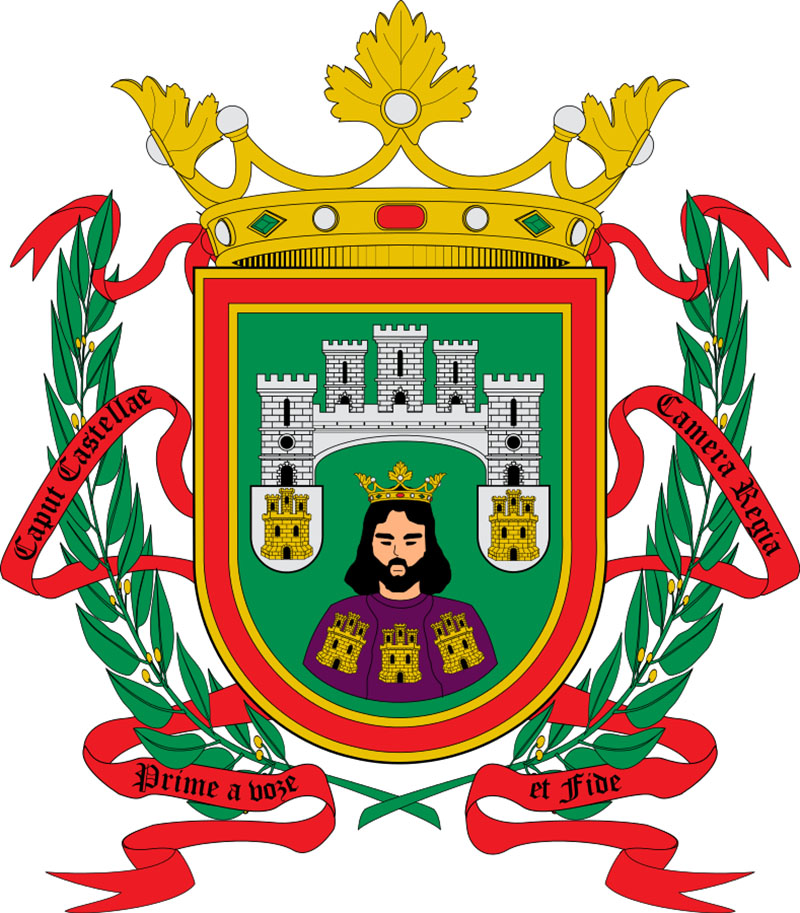

So following good advice, I have made it to Madrid to experience the beauty of the city and its architecture. Madrid has beauty, architecture, but one other trait I must add is something I have coined "architectural honesty." The folks in Madrid are keen lovers of architecture and certainly very proud of theirs but alas, the same ‘Madridians’, or more accurately Madrilenians, having noticed that I am on a hunt for exceptional cathedrals, sent me away from Madrid to a place called Burgos. Burgos is about 250 km North of Madrid. I gather from Wikipedia that it is a town of a little less than 200,000 inhabitants and a capital city of the Burgos Province. Founded by the Castilian Count Diego Rodriguez in 884 AD as an outpost of the Asturian Kingdom, Burgos is now regarded as the principal crossroad of the North of Spain. A striking Coat of Arms of the city of Burgos further accentuates the city’s stateliness. It has a pronounced use in and around the city centre. It features the burst of a crowned king. The crown has rhinestones and acanthus flowers interpolated with pearls. Also seen on the arms is a huge castle with three crenelated towers. These towers stand for the three regions where the crown of Burgos has jurisdiction and property.

Everywhere you turn for information of this town, you are sure to be confronted with this piece of information which states—Burgos has many historic landmarks but most prominent of them all is the remarkable Burgos Cathedral which was declared a World Heritage site by UNESCO in 1984. Madrid has several cathedrals but the way the people of Madrid spoke of Burgos cathedral is nothing short of a marvel. One is then left to wonder who is prouder of the cathedral, the people of Burgos or the warm Madrilenians.

Fig. 1: A view of the western Façade of the Catedral de Santa Maria de Burgos.

Fig. 2: A view of the western front from a slightly elevated position.

Fig. 3: An interesting marriage of both Gothic and Renaissance treatment of a doorway in the western front just below the rose window.

Fig. 4: A view of the Burgos cathedral water fountain with the central arched doorway of the western façade in the background.

Fig. 5: The Coat of Arms of the City of Burgos showing a golden crown and the huge castle with three crenelated towers which represent the three areas of Burgos’ jurisdiction.

So off to Burgos I went and on arrival, it was straight to the famous Burgos Cathedral. To see Catedral de Santa Maria de Burgos—as the cathedral is traditionally called—is to understand its allure and the grip of wonder it has on the people. The beautiful church is an—or for me, the—epitome of pureness of Gothic form made manifest in Spain. Some may frown at this submission however, and this would be understandable. It will be very easy to argue that while the Catedral de Santa Maria de Burgos, for the most part, is very Gothic in character and appearance, it is in no way a pure example of Gothicism. The Catedral de Santa Maria de Burgos took so many years to construct, so it consequently exhibits a multi-style character, from Romanesque through to Baroque. After the initial construction work on the cathedral, the high altar was consecrated in 1260, and then there was a long interruption of about 200 years before construction would start again. All these while, the worship grounds were in use. Thus, there is merit in the argument that Burgos is particularly Gothic, no doubt, but not the epitome of Gothicism. But, to speak of pureness of the Gothic style, one must make reference to France and its pioneering efforts at developing the ideologies that define and guide the style. The very gene and character of the Gothic vocabulary is probably more advanced in France than anywhere else, while the Gothic expression found anywhere in Europe can itself be valid in substances and gaudiness without necessary links to French beginnings. It perhaps becomes expedient not to overlook, or take it lightly in any manner, should one find a sort of direct connection to the source, particularly in the use and articulation of French styled Gothic vocabulary. As John Gade puts it in his seminal work titled Cathedrals of Spain, Burgos Cathedral is singularly picturesque and by far the most interesting of the three great Gothic cathedrals of Spain,—Leon, Toledo, and Burgos. The interest is mainly due to her vigorous organism, an outcome of more essentially Spanish preferences as well as a natural interpretation of the French importations.1 It may also be noteworthy to mention that a Frenchman called Enrique is named as the principal architect for Burgos cathedral in the 13th century. Master Builder Enrique is also famed to have worked on Leon Cathedral. Later however, in the 15th century, the German builder Juan of Cologne also worked on the cathedral, particularly on the two spires of the western end on invitation of Bishop Alfonso. However, Alfonso would never see the final work as he died before the two spires were completed.

Fig. 6: Details of the Cimborrio octagonal tower over the transept crossing.

Fig. 7: Main entrance on the southern end of the cathedral—the Sarmental Façade. The tympanum and statues were elegantly detailed.

Fig. 8: The octagonal shaped ceiling of the main chapel surrounded by walkways high above.

Fig. 9: Details of the ornate piers below the octagonal main chapel in the Burgos Cathedral.

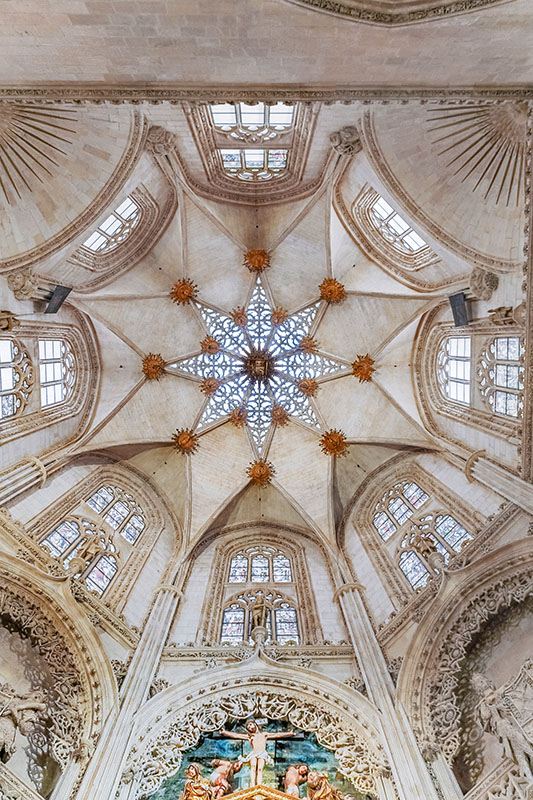

Fig. 10: Details of the ornate star shaped ceiling of the main chapel in Burgos Cathedral.

Fig. 11: The high gates of the central cathedral choir.

Fig. 12: The star shaped vault ceiling over the Chapel of the Constables in Burgos Cathedral.

Fig. 13: A view of the star shaped vaults above the chapel of the Constables in Burgos Cathedral.

Fig. 14: Parts of the choir stalls with overhanging Gothic styled chandelier lighting. A part of the two faced organ can be seen to the top left in the background.

Like many great gothic cathedrals we see today, the Catedral de Santa Maria de Burgos stands on the site of a much older Romanesque church, which gave way to the newer and bigger building we have now. King Ferdinand III of Castile is famed to have ordered the construction of a cathedral at Burgos on the nudging of Bishop Maurice, an Englishman who became bishop from 1213 to 1238. Maurice’s missions took him through those parts of Germany and France where the enthusiasm for cathedral-building was at its height, and he had time to admire and study a forest of exquisite spires, while on his sojourn. Naturally he returned to his native city burning with desire to begin a similar work there, and probably brought with him master-builders and skilled artists of long training in Gothic church-building.2 The foundation stone on the site of the former Romanesque church was laid on July 20, 1221.3 The current edifice boasts of three naves and an amazing routine of chapels with an array of the best examples of 14th- and 15th-century decorative sculptures. The central nave is higher and wider than the two lateral ones.4 The cathedral dome features a brilliant Mudejar vault.

While one cannot miss the bold Italian renaissance style finish of parts of the great church, the interior of Burgos cathedral is classically French in taste. It presents some of the finest examples of gilded sculpture of the time. The northern transept arm is occupied by the great Renaissance style "golden staircase" leading to the Puerta de la Coroneria, which has been closed for a long time now. The sublime piece is rich in effect, faithful in detail, and of strong expression. Carefully situated in relation to the masonry, it ornaments the northern end of the transept with much perfection and splendour. Further, the gilt metal railing in the interior of the cathedral is as exquisite in workmanship as in design. It was created by the renowned master craftsman and architect Diego de Siloé. Siloé was the architect of the cathedral in the beginning of the sixteenth century.

The main façade of the Catedral de Santa Maria de Burgos features a gallery of statues of the Castile monarch that are, in a sense, reminiscent of the gallery of kings on the Notre Dame Cathedral of Paris and that of Amiens. Both the gallery of statues of the Castile monarchs and the starred rose window of the Puerta del Perdon are flanked by two 82-meter towers with magnificent 15th-century spires on each. These spires have become the mark of identity for the Burgos Cathedral. They stand like twins holding hands on a slow, long walk. These brilliant works of Juan de Cologne now define the skies of Burgos; they have become the handsome duo towering three hundred feet above the heads of the multitudes below. The Catedral de Santa Maria de Burgos’s twin towers are such a glorious site to behold.

Fig. 15: La Escalera Dorada (The Golden Staircase) was designed by Italian architect Diego de Siloé in 1523.

Fig. 16: In the heart of the cathedral, the beautifully gilded altar piece of the main chapel.

Fig. 17: Alter piece in the Chapel of the Nativity.

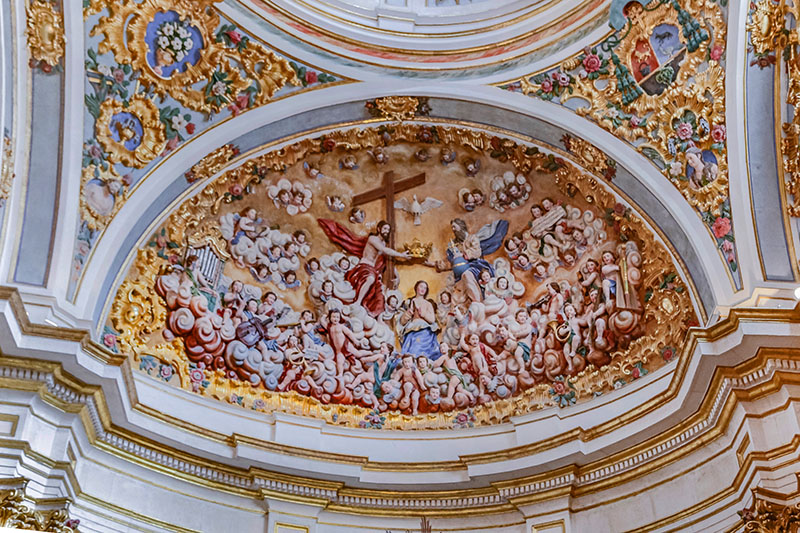

Fig. 18: Oval cupola of the Nativity Chapel with medallions of Saints in Burgos Cathedral.

Fig. 19: A gilded ornate altar piece of the chapel of Constable in Burgos Cathedral.

Fig. 20: Details of the Chapel of Constable altar piece.

Fig. 21: The beautifully detailed ceiling art of the main sacristy (Sacrestía Mayor) inside the Burgos Cathedral.

Fig. 22: Baroque style ornamentation of the ceiling of the cathedral sacristy lantern copula.

A Short Note on Valladolid

About 127 kilometres southwest of Burgos is the former Celtic settlement area now known as Valladolid. Valladolid is beautifully lodged between two rivers, Pisuerga and Esgueva, very much like the ancient city of Mesopotamia, and quite like Mesopotamia, this northern Spanish city is indeed a lovely place with a rich array of flora. Valladolid was very briefly the capital of Spain in the 17th century under Phillip III, before the position was inevitably returned to Madrid. Valladolid is also famous for being the city where the great explorer Christopher Columbus died in 1506. Originally from Genoa, Columbus had moved to Portugal and later to Spain. Columbus, on the patronage of King Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile who themselves got married in Valladolid 1469, made several transatlantic voyages before he fell gravely ill and died on the 20th of May 1506, believing that he had reached the Indies, and the place where he drew his last breath is now a museum created in his honour.5

Being a rather strategic district of political and social influence, the city boasts of several iconic buildings—not only regal, but political, artistic and religious in function as well. The Valladolid Cathedral, officially called La Catedral de Nuestra Senora de la Asuncion (The Cathedral of Our Lady of Holy Assumption) is a prominent structure in the city. Originally designed by Juan de Herrera, it was to be the biggest religious structure in the whole of Europe but was never fully built. Another very interesting building in Valladolid is the National Museum of Sculpture, also called Museo Nacional de San Gregorio. The museum was founded in 1842 and it houses an array of works that span over 600 years from paintings to sculpture.

Of all the buildings in Valladolid, I took particular interest in the San Pablo de Valladolid (St Paul’s Convent Church) building. From the west end, the building presents a detailed ornamented façade that appears to be sandwiched between two relatively plain towers that house the church bells. A sparsely ornamented, but nonetheless interesting cross stands majestically in the front of the church overlooking it like a guardian. Beyond this cross is a line of stone pillars that appears to act as a barrier. These small pillars mounted by crests holding creatures are now quite abraded and it’s hard to tell with all certainty what creature they are, but beyond this, one can confidently say that they add a kind of firmness and sense of character to the main structure, which is clearly of Gothic extraction by all rights.

Fig. 23: A view of the western façade of the San Pablo de Valladolid. Notice the cross in the foreground.

Fig. 24: An abstracted view of the main entrance door and the details of the ornamentation on the western façade of San Pablo de Valladolid.

Fig. 25: Sculptural details on the western façade.

Fig. 26: Details of the sculptural ornamentation and the Rose window on the western façade of the San Pablo Church in Valladolid.

Fig. 27: Another view of the sculptural ornamentation of the western façade.

Fig. 28: Abraded creatures holding crests on short stone columns in front of the San Pablo Church.

Fig. 29: The cross majestically positioned in front of the San Pablo church.

Fig. 30: A view of the main door way and the richly ornate ogival styled arch about it.

Fig. 31: The church pediment braced on both sides by the tip of the church towers. Inside, one will catch a glimpse of the church bells.

Fig. 32: The heavily ornate entrance of the National Museum of Sculpture in Valladolid.

Fig. 33: A close up of the relief sculpture on the façade of the National Museum of Sculpture in Valladolid.

The San Pablo church was commissioned by Juan de Torquemada in the mid-15th century and Simon de Colonia is favoured to have designed the façade we see today. Though the building did not have the type of patronage that one will see in a big city cathedral, it has presence that tells you it is important. San Pablo de Valladolid has had its fair share of history making events. The most recent might be the case of a young Muslim man charging into the church during a wedding ceremony earlier this year, making quite a scene. The young man from Morocco is said to have been shouting ‘Allahu arkbar’ as he ran towards the alter destroying the alter cloth and giving the wedding guest quite a scare as they thought he may be armed or might be on a suicide mission. He was later arrested outside the church building.6 There was thick suspicion in the air as visitors walked around and took photographs of the building. I do not want to sound paranoid but I would swear that my every move was keenly watched by the security—as most times, I was the only person of colour (African descent) there. It is usually upsetting that people move away when you come close to share a view. However, in my travels through the year, I have learnt to ignore the ignorance, empathise with them as they struggle with their fear of the unknown, and uncompromisingly, enjoy the architecture!

1 Gade, John Allyne, The Cathedrals of Spain. (Cambridge: The Riverside Press, 1911) 36.

2 Ibid., 38.

3 Huylebrouck, D., Buitrago, A.R., Iglesias, E. R., “Octagonal Geometry of the Cimborio in Burgos Cathedral,” Nexus Network Journal Vol.13, No. 1, 2011, 195, DOI 10.1007/s00004-011-0057-5; published online 26 February 2011.

4 Ortega, L.M., Perelli J., Alberruche, J., “The Spires of Burgos Cathedral,” In Structural Analysis of Historical Constructions.

5 Roger Crowley. Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the first Global Empire. (New York: Random House, 2015) 161.

6 Mclaughlin, K., "Fanatic storms a Spanish wedding shouting 'Allah is great'," Accessed 20th December 2017.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top