-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Missing Decades, Hidden Labor: Reconstructing and Interpreting Industrial Heritage in South Africa

There is nothing magical about a gold mine. Barren and pockmarked, all dirt and no trees, fenced in all sides, a gold mine resembles a war-torn battlefield. The noise was harsh and ubiquitous: the rasp of shaft-lifts, the jangling power drills, the distant rumble of dynamite, the barked orders. Everywhere I looked I saw black men in dusty overalls looking tired and bent. They lived on the grounds in bleak, single-sex barracks that contained hundreds of concrete bunks separated from each other by only a few inches. (Nelson Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom, Chapter 9)

Standing in Pretoria’s Church Square a few weeks back, the sounds and sights of urban construction were omnipresent. Dozens of workers hefted shovels and axes under the midday sun as part of a new public work, stripping the existing surface of the square in preparation for a larger renovation. As I paused to snap a few photos of the statue of Dutch Boer president Paul Kruger at the square’s center, I heard laughter as a voice from behind me called out “You should take our picture — we are the real heroes!” A construction worker and his crew reclined nearby, having sought out the scant shade available to enjoy lunch and a much-deserved break. He said I wouldn’t be able to pronounce his Zulu name, but in English his name means “Praise God.” We talked politics (he’s a big Trevor Noah fan) and swapped stories about the places we grew up. He spoke incisively of the rampant corruption and unemployment in South Africa, which by current calculations hovers around 25%.1 Though he dreams of better pay and more fulfilling employment, in this economic climate, construction work is at the very least a job. As we parted ways, my husband asked how the future looked for him. Praise God shrugged and said, “It’s survival, my man. We just try to survive.”

Praise God (front center) with his colleagues. This photo by my husband, John Golden.

Standing there in the literal and proverbial shadow of Kruger, amidst the rubble and noise of new construction, I thought about how the historical spaces and places of South Africa continue to reverberate in the country’s tumultuous present. Especially here, in this place where the built environment was being actively remade, the rapid reinvention of South Africa over the last 150 years felt palpably present. This is after all, a young country, forged from the systematic and industrialized extraction of gold and diamonds, rising now from the rubble of one of the greatest human rights violations in recent history.2 In my capacity as the 2017 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellow, I’ll be spending the next year exploring the life and afterlife of industrial heritage sites across the globe—how they are being interpreted for public audiences, adaptively reused, left to decay in place, or razed and forcibly forgotten.

A rare public recognition of the economic role of mining labor during the Industrial Age. Sculpture by Andile Msongelwa, May 7, 2013. The inscription on the back reads: “During the 2007 wage negotiations, the Chamber of Mines of South Africa, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), UASA - The Union and solidarity agreed to recognize the role played by mineworkers in developing the economy of South Africa. This monument represents the symbolic and historical role played by mineworkers in shaping the economies of the mining towns and labour sending areas in particular and that of South Africa in general. We salute these economic heroes who risked their lives to make Johannesburg one of the most economically vibrant cities on the continent. We value their contribution to the economy and will strive for quality education for our children and the development of skills of mine workers to enable them to play their rightful role in the continued economic development of mining communities, labour sending areas and of the country as a whole.”

As heritage sites, industrial places from the nineteenth century onward occupy a strange and tenuous place within current practices of global public history. Early spaces of industrialization are key to understanding the concept of the “Anthropocene,” the now ubiquitous trans-disciplinary term for the geological age in which humans have dramatically and irreversibly altered the structure and climate of our planet. These sites, which in addition to rarely conforming to standard conceptions of aesthetic appeal, are frequently characterized by historical practices of labor exploitation and environmental pollution. Often existing at massive scale, they can be difficult to adaptively reuse. Many have left their sites and surroundings damaged, both environmentally and socially.3

The first stop on my itinerary is South Africa, where I’ve spent the past six weeks exploring the urban center of Johannesburg, before roadtripping from the mountainous Highveld region of Mpumalanga in the northeast, across the rugged central plateau, down the lush corridor of the Garden Route, and finally to Cape Town. During that time, I visited many sites of industrial production (mines, factories, ports, wineries), and the buildings constructed on the wealth generated and accumulated from those sites (company towns, museums, manor houses, hospitals, clubs, etc.).

Across all of these different sites, rural or urban, hundreds of meters below ground or at the top the tallest building in Africa, I have been struck by the extent to which the architectural histories of industrialization and apartheid are inexorably linked. However, how (and even if) current public interpretation acknowledges that connection has varied significantly across the sites on my itinerary. As I’ve witnessed in South Africa, public history-making reveals a great deal about how a country conceptualizes of itself—its aspirations and self-perception are deeply embedded in how the past is being presented to public audiences, local and tourist alike.

In selecting sites for my fellowship travels, I relied heavily on the UNESCO World Heritage list, as well as the list of tentative sites maintained by UNESCO that are intended for current or future nominations. South Africa currently includes no industrial sites on its tentative list, which struck me as strange, since the mining industry has had an outsized impact on the economic development, urban planning, and built environment of the country over the last century and a half. However, the absence of industrial sites on the list is, in fact, a relatively recent development. In 2015, South Africa dramatically reconfigured the cultural sites included on its tentative list, removing several significant and endangered industrial heritage sites, including the mining town of Pilgrim’s Rest, the open mine at Kimberley and its associated historic structures, and the Namaqualand Copper Mining landscape.4 The justification for the change is not entirely clear, though those in the heritage business here have speculated a number of different reasons, including the desire to conserve resources and target sites with the most chance of achieving World Heritage status.5

The mining town of Pilgrim’s Rest is one of the sites de-listed from UNESCO tentative list. Today, the dwindling tourist economy seems to be barely supporting the town.

Only two modern cultural heritage sites survived the 2015 cuts: the Early Farmsteads of the Cape Winelands and the Liberation Heritage Route. A third was also added during the reorganization, which partially overlaps with the latter listing: Human Rights Liberation Struggle and Reconciliation: Nelson Mandela Legacy Sites.6 Based on my observations over the last month, this current list reflects South Africa’s preservation priorities, each of which connect to certain kinds of buildings and historical sites. The first of these paradigms is anchored firmly in the colonial pre-industrial past, and is still largely dominated by the stories and places of white colonists and settlers, mainly of Dutch Boer or British descent. The second centers on the young democracy’s ongoing attempt to grapple with the recent, and still very raw, memory of apartheid. Sites that fall into one of these two categories are virtually inescapable in the touristic landscape of South Africa.

Like an archaeologist peeling back stratigraphic layers of European architectural influence, my road trip across South Africa has taken me progressively deeper into the built remains of the past. The International Style office buildings in downtown Jo’burg and apartheid-era township housing of Soweto gave way to the late Victorian corrugated tin of mining towns in the Mpumalanga Province, then to rusticated brownstones in the Northern Cape, and eventually to the white-washed gables of Cape Dutch manor houses in the agricultural lands of the Western Cape.

Driving west from Wilderness to Franschhoek a few weeks back, my husband and I stopped for an afternoon break in Swellendam. By this point in our drive, much of the historic building stock was firmly late seventeenth- or eighteenth-century, dating to the late days of the Dutch East India Company. This is the architectural heritage that has been carefully preserved at Swellendam’s Old Drostdy Museum, an impressive complex of historic and new buildings meant to evoke life in the late 1700s under Dutch colonial rule. Here, the second oldest jail in South Africa opens out onto a courtyard (or Ambagswerf in Afrikaans) of recently constructed thatched buildings, each housing the trappings of a different trade, such as tanning, milling, cobbling, and barrel making. Across the street, the Drostdy (or magistrate’s house) stands as an exemplar of early Cape Dutch architecture. In addition to reconstructed period rooms, one hallway charts the development of the Cape Dutch vernacular through the various expansions and changes made to the manor over time. Mayville, another, smaller house from the mid-nineteenth century illustrates the changing lifestyle of Swellendam’s middle class.7

Cape Dutch heritage at the Old Drostdy Museum in Swellendam, South Africa. While the prison and the Drostdy (or magistrate’s house) both date to approximately 1750, the mill is a modern recreation that is part of the Ambagswerf, or trade yard, meant to demonstrate a variety of pre-industrial occupations.

Old Drostdy is typical in many ways of the architectural heritage that has survived through apartheid and continues to flourish under South Africa’s democratic government. When apartheid ended in 1994 and Nelson Mandela became the country’s first democratically elected leader, the new government took stock of what had constituted heritage under the previous regime. What they found was a strong bias towards sites that emphasized the role of white, colonial actors.8 In particular, many national monuments declared under the National Party’s apartheid government were colonial sites located in the Western Cape, the province that includes Cape Town. By prioritizing early Dutch manor houses on historic farms and vineyards above other kinds of buildings, the National Party sought to legitimize its claim to power through association with this particular architectural tradition. So while heritage conservation in South Africa has broadened to include more diverse buildings and landscapes since 1994, it is undeniable that many of the sites valued by the apartheid regime have been well cared-for and remain in excellent condition today. The public history challenge for these sites has been to reframe the stories and meanings of these places in light of post-apartheid attempts to decolonize history, giving voice to non-white actors and telling a more inclusive range of stories. Places like the great Dutch colonial farms must confront the ways in which, as landscapes of power, they perpetuated the systematic disenfranchisement of non-white people, either overtly through the institution of slavery, or through more insidious means, such as the establishment of pass laws or other legislation meant to restrict freedom of movement.

Many of the historic Cape Dutch sites such as Old Drostdy use the methods and strategies of vernacular architecture in a public history setting. Diachronic explorations of changing floor plans such as this are common in Cape Dutch manor houses. Equivalent analysis is rarely found at industrial sites.

At many of the colonial sites on my South African itinerary, the move towards restorative justice through public storytelling seems to be happening slowly and incrementally. In the former stables of the magistrate’s house at Old Drostdy, a small installation about slavery sits next to the historical carriage and saddles. And in the main house, one of the rooms has been set aside for a short exhibition about the life of Nelson Mandela. Indeed, the inclusion of what might be termed a “Mandela room” has been undoubtedly the most frequent intervention towards telling the story of apartheid and the freedom struggle. This is true of almost all historic sites I’ve visited, including those with little to no historical connection to Mandela.

At the McGregor Museum in Kimberley, one of the featured exhibitions highlights Mandela’s connections to the Northern Cape Province. Designed by D.W. Greatbatch, and completed in 1897, the McGregor Museum began its life as the brainchild of Cecil Rhodes, infamous British colonialist, diamond magnate, and instigator of the Anglo-Boer War. Having made his fortune in the diamond mines of Kimberley, Rhodes funneled much of his wealth into the architectural betterment of the city, including this building, which he imagined as a sanitarium. The “sanitarium” quickly became a hotel, and later served as Rhodes’s hideout through the Siege of Kimberley during the Anglo-Boer War. The ballroom, the best-lit and most prominent exhibition space in the museum, is now occupied by the Mandela material.

Mandela, as a figure who is universally revered in South Africa, in public history settings has become a less controversial or objectionable way of acknowledging the apartheid past. If my experiences at Robben Island (where Mandela was held for 18 years during his prison sentence) or at his home in the township of Soweto are any indication, Mandela tourism is a big draw for both international and domestic audiences. The Mandela sites seem to be so attractive and effective in part because they give a face to the apartheid story. If we consider the spaces of apartheid as those meant to dehumanize through containment, surveillance, incarceration, and de-personalization, Mandela provides an entry point into that larger landscape. Consider Soweto (short for Southwestern Townships), a sprawling conurbation that today houses some 1.2 million people and during the 1970s and 1980s was a hotbed of resistance to apartheid. The environment of Soweto is one of seemingly endless houses constructed in succeeding waves as black Africans were displaced and relocated from their homes in and around Johannesburg. The scope of Soweto is staggering, but many visitors seem to find the connection to Mandela’s story a way of grasping Soweto. Sadly, the areas directly adjacent to the Mandela house (a block that also includes Desmond Tutu’s home) have been architecturally and economically transformed to suit the demands of tourism. As my husband put it, this area felt like “Disneyland Soweto,” sanitized for mass tourist consumption. Fortunately the same cannot be said for Robben Island. This inscribed UNESCO site has retained the full force of its austerity since its conversion from prison to historical site. The only material difference between Mandela’s cell in B-Block and the rest of the cells on the long corridor is the addition of a standard-issue red bucket, of the kind prisoners would have used as toilets.

The photo of the roadside stand, taken by John Golden, is from an area of Soweto that was a men’s hostel (basically a fenced compound for workers) during apartheid. Note that you can buy a fat cake (fried dough) for 1 Rand, or about 7 cents US. The video, also by John Golden, shows a more developed portion of Soweto, comprised of houses built in the 1970s. Both are extremely different urban conditions from the area shown in the third photo, which depicts the streets around the Mandela and Desmond Tutu houses. Here, many of the houses have been upgraded over time, the roads are well-maintained, and space has been made for tour bus parking.

If Mandela/Freedom Struggle sites and Cape Dutch architecture are the two major cornerstones of preservation right now—representing a pre-industrial colonial vision of the country, and the troubled time during and after apartheid—this still presents a narrow and incomplete reckoning of South Africa’s architectural heritage.9 What has been left out is the period between the beginning of mining consolidation and the official start of apartheid, between roughly 1890 and 1948. Critical for understanding what would come afterwards, it was during this period that much of the groundwork of apartheid was laid. Apartheid, as a spatial strategy of separation, was in large part made possible by the existing reconfiguration of the economic and built landscape of South Africa that accompanied industrialization. Many of these tactics had been first pioneered under slavery, but were radically accelerated and expanded during the early twentieth century, creating mass-produced spaces of racial segregation that mirrored the logic of industrial resource extraction and the manufacture of consumer goods.

This critical epoch in South Africa’s history is notably absent even at actual industrial heritage sites with intact buildings and material culture dating from this period (including those removed from the UNESCO tentative list in 2015). The Kimberley Mine Museum and historic village, a DeBeers-funded spectacular complete with tiny, intricate dioramas of the historic mine and a flashy, outrageous “diamond room,”10 seems to pointedly sidestep the period after the mine’s consolidation. Compared to many similar historical sites in South Africa, which are sadly understaffed and underfunded, the Kimberley complex is a festival of high-production-value multi-media installations. But underneath all of that flash, the museum ultimately emphasizes a relatively narrow story—one that ends precisely before the initiation of industrialized mining.

In many ways, Kimberley was the site that triggered the “Mineral Revolution” of South Africa. After the discovery of diamonds in 1866 sparked the first major diamond rush in the region, Kimberley generated much of the wealth and capital that then fed future mining exploits in and around Johannesburg and further east towards Cullinan, Pilgrim’s Rest, and Barberton. The diamond and gold mining boom fundamentally altered the political and economic landscape of the region, triggering the accumulation of wealth into the hands of a few, and the aggregation of people and culture in new urban metropolises such as Pretoria and Johannesburg.

Kimberley was the first city in the Southern Hemisphere to install electric street lighting, some of which has been preserved as part of the historical complex near the Big Hole. It also featured an early electric streetcar system, which for 10 Rand (about 75 cents), visitors can still ride. The most exhilarating part of the trip was when the streetcar unexpectedly departed the historical village and continued out onto modern roadways outside the complex. Given that the streetcar only runs when there are enough passengers to fill it, its appearance on the streets of Kimberley must not be terribly frequent, which would explain the surprise and confusion of pedestrians and drivers we encountered.

At Kimberley, the initial mining process was one of individual claim owners mining small tracts of land, often no more than 4 x 4 meters. Miners dug these claims with hand tools and the assistance of inexpensively hired indigenous workers. However, once the holes became too deep to be profitably mined by hand, and makeshift scaffolding began to cause insurmountable safety problems, more machinery and organized labor were required to construct underground tunnels. The requirement of more industrialized means of extraction necessitated the consolidation of the mining industry. At Kimberley, the DeBeers company eventually amassed a monopoly and took complete control of the mine. In Johannesburg, where early surface-level mining quickly gave way to heavily engineered deep mining, the diamond magnates of Kimberley bankrolled the digging of gold mines, and further enriched themselves in the process.

Some of the more subtle and effective interpretive devices at Kimberley were the painted “claims” that covered the floor of the main exhibition hall. It was helpful to actually experience these claims at scale, which, given the size of the Big Hole, gave some sense of just how many miners might have been working in the early days of the mine. The subsequent dioramas show the contrast between the early decades of opencast mining, where miners maintained individual claims and constructed scaffolding as the mine went deeper, versus the capital- and machinery-intensive underground mining process of the consolidated DeBeers company.

The interpretive apparatus of the Kimberley Mine Museum places an overwhelming emphasis on the period before the consolidation of DeBeers. The twenty-minute movie that is at the heart of the visitor experience tells the story of a British journalist and a native African laborer who separately travel to Kimberley to seek their fortunes. With its raucous saloons, diamond markets, and brothels, the cinematic portrayal of early Kimberley recalls popular conceptions of the American Old West. The film concludes with the two protagonists disenchanted and abandoning the mine in the late 1880s. This tendency to romanticize the rough-and-tumble scrabble for gold in the mine’s early years is carried on throughout the museum, where the exhibits play up the “heroic” actions of early diamond magnates, the geological processes through which diamonds are created, global myths and traditions about diamonds, and the present-day manufacturing of diamond jewelry. The life and experiences of workers in the mines during the period from roughly 1890 to the mine’s shutdown in 1914 are peripheral at best. Any discussion of the function and operation of the modern DeBeers corporation is markedly absent.

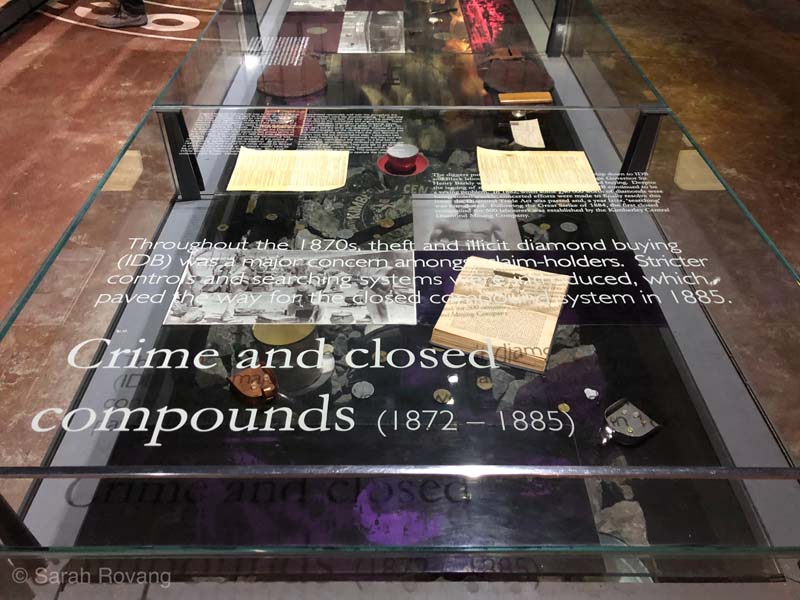

Consolidated mining companies such as DeBeers frequently owned company towns and exerted extreme control over the built environment of their workers. Under the justification of “preventing diamond theft,” black African workers were increasingly restricted to tightly controlled compounds characterized by overcrowding, inadequate sanitation, and insufficient food. Workers were subjected to invasive strip searches each day when moving between mine and compound. During the early twentieth century, the compound system rapidly spread to other industries, becoming in many ways the precursor of the townships and hostels that predominated during apartheid. Compounds were planned on strict geometries, which enabled maximum surveillance and control. Different tribal groups were not allowed any contact, a move that mine owners typically justified as “preventing ethnic strife,” but which, in actuality, helped prevent the organization of labor across tribal lines.11

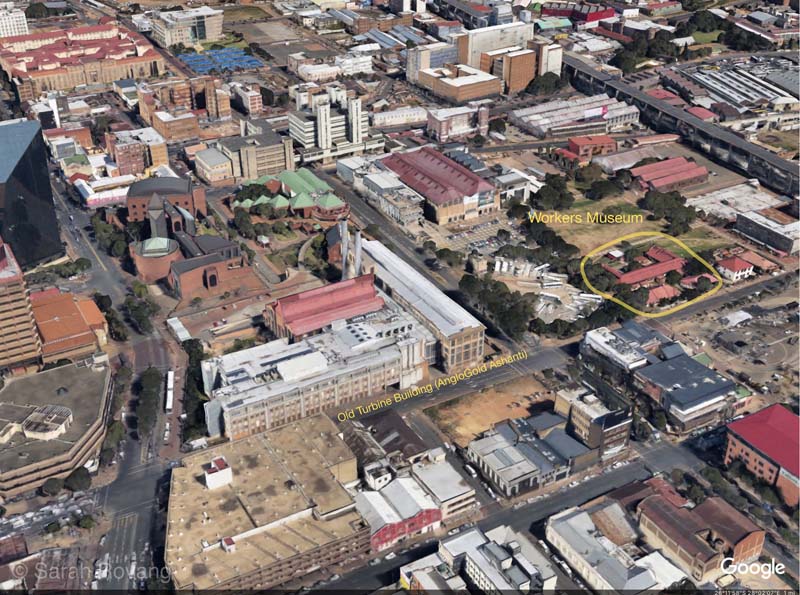

Although most major industrial sites in South Africa had associated worker compounds at some point in history, few of these sites have survived, and even fewer are accessible to the public. One exception is the fantastic Worker’s Museum in Johannesburg. This museum, which unfortunately did not allow photographs, very convincingly argues that the struggle of apartheid was largely synonymous with the struggle for organized labor. Housed in a 1913 compound that was home to the workers at Johannesburg’s electric utilities company, the museum’s main “artifact” is the historic built environment itself, which is effectively cast as a microcosm of the larger demographic and cultural shifts that accompanied urbanization and industrialization in South Africa.

Situated in the heart of Newtown in Johannesburg, the Workers Museum is further distinguished by its location near the original worksite of the laborers—the electric utilities building across the street. The former turbine building is one of South Africa’s outstanding examples of industrial architecture adaptively reused, and a topic for a future blog post.

The workers who lived in compounds like this one came not only from the local area, but migrated from other parts of South Africa in search of better work and opportunities. Many of the rural hardships experienced in the late 1800s and early 1900s were strategically manufactured to “encourage” (read: coerce) rural men to leave their families and seek work in urban areas. Artificially high “hut taxes” and other forms of exploitation made village living so difficult that many men had no choice but to try their chances in a job where they would be forced to live in a compound for nine months out of the year. Reproductions of letters of complaint written by compound residents testify to the harsh conditions of daily life, as do the buildings themselves. The main exhibition space at the museum is one of the dormitories where black workers lived in crowded, filthy conditions—a stark constrast to the separate houses where their white counterparts resided in the very same compound. Recreational spaces for the black workers were incidental rather than part of the design (the yard could also be used for chatting, games, or the “gumboot” dancing developed by miners as a pastime). By contrast, disciplinary spaces occupied an outsize position in the complex, with corporal punishment carried out in the central courtyard as a warning to other workers. However, as much as compounds confined and restricted movement, they were also sites of resistance and frequently fertile ground for organized labor movements. The Worker’s Museum charts the development of union action through the twentieth century, crediting organized labor with some of the most effective actions taken against the National Party’s apartheid regime.12 Given the role of organized labor in the freedom movement, it is not surprising that South Africa’s constitution now guarantees the right of workers to unionize.

The week after my visit to the Workers Museum, I spent several hours 763 meters underground in the Premier Diamond Mine, an operational mine located in Cullinan, about an hour northeast of Johannesburg. After resurfacing, I attempted to track down the mine’s historical worker compound. Before the mine tour, I’d spent the morning wandering around Cullinan’s Main Street, which is comprised of quaint, stone houses converted into shops and cafés (previously occupied by white miners and managers). It’s very easy to buy a diamond in Cullinan, or to see a recreation of the Cullinan Diamond, which is now part of the British Crown Jewels. And a visitor can view virtually any piece of historical mining equipment, thanks to the free open-air museum and children’s play area (“You climb on the machinery at your own risk!”). However, as far as I could discern, visiting the worker’s compound is currently impossible for a tourist. A panel about the worker’s compound in the small mining museum played up the “upgrades” made to the compound over time, which provided the workers with more recreational options over the years. The museum did not, however, include any indication of where the compound was located on the site or whether it was open to the public. Using what little information I could find online to locate the old worker’s compound, we drove out on a dirt road until we were eventually confronted with a concrete barricade and a barbed wire fence. A report on the Heritage Portal concerning South Africa’s most endangered heritage sites noted that the Cullinan compound is currently in danger of subsiding into the open mine pit, irreparably damaging this complex, and with it, severing the architectural connection to the stories of thousands of workers over the course of the twentieth century.13 Although apartheid officially ended in 1994, its aftereffects certainly echo in places such as Cullinan, revealing the disparities in whose history is being preserved and made accessible to public audiences, and whose history is hidden behind a barricade and left to the forces of time and gravity.

Part of the challenge I’ve faced in this first six weeks of travel has been to develop a working method for decoding richly-layered and complicated public history experiences like those at Cullinan, Kimberley, and the Worker’s Museum. The public storytelling component of my project has added a “meta” layer to what I’m looking at in any given site; not only am I investigating the historical architecture itself, but also analyzing all of the other narrative devices and aspects of that architectural experience. As part of my documentation process, for instance, I’ve been creating audio recordings of the various places I’ve visited. This process has heightened my awareness of how auditory cues are deployed to evoke certain experiences, and the ways in which that sensory input alters the visual and bodily experience of moving through a historical space. Particularly interesting have been the instances (such as the one heard in the sound clip below) where certain media or devices are telling one story, while another story is being told by the lived experience of the site. This will be a topic to which I will be undoubtedly returning in future blogs.

In contrast to the vision of pre-industrial Kimberley given by the main exhibition hall, movie, and open-air historical village, the audio installation included in a small mock-up of the underground mine tells a different story. In this sound installation, which includes a dramatic simulated dynamite explosion near the beginning, the industrial process of underground mining (of the type that happened from the late 1880s through 1914) is vividly brought to life. The intensity and volume of the sound gave some slight indication of the poor working conditions faced by underground miners, foreshadowing Mandela’s description in the epigraph of this post of a cacophonous 1940s gold mine in Johannesburg.

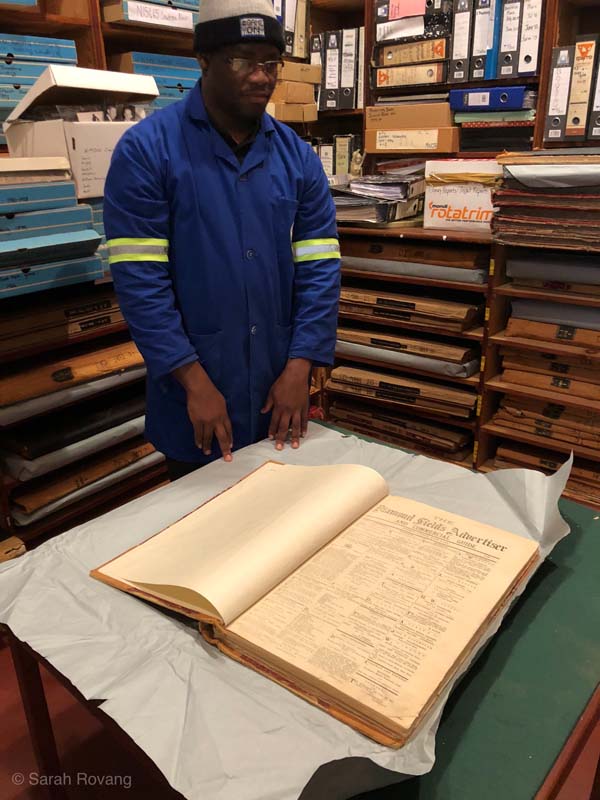

On my second day in Kimberley, having toured the Mine Museum and seen the famous Big Hole, I arrived at the Africana Library, which advertises one of the best collections of historical photographs and records in the Northern Cape. This beautifully-preserved 1887 building originally functioned as Kimberley’s first public library, its collection assembled largely out of donated books brought to Kimberley by those who had come to seek their fortunes in the mine. Our tour guide, Michael, also serves as an assistant librarian and archivist. A longtime resident of Kimberley, all of his training has been in-house, conducted on an as-needed basis. Faced with a harsh, arid climate and limited resources, the library has been forced to triage the preservation of its collection, digitizing the oldest and most fragile works before they disintegrate. Michael glowed with pride as he described the recent purchases made possible by a grant from the National Lottery: a new book scanner and a climate control system for one of the rooms in the stacks. Despite his white-collar job, Michael wore the ubiquitous blue jumpsuit with green neon reflective stripes donned by so many workers in South Africa. His garb brought me back to my conversation with Praise God, whose crew wore the same attire. Beyond providing a decent living, heritage work was clearly providing Michael with a means of engaging with the past and future. Further, jobs like Michael’s promote greater inclusion in the production of public history, expanding who has a true stake in the creation and performance of heritage. In South Africa, it’s not nearly enough to increase public access to historic properties, or to simply include more and varied sites on the UNESCO tentative list (though these things are certainly important as well). More people need to feel like stakeholders in heritage; included in the ongoing and still troubled process of reconciliation. Facing a lack of funding and pernicious government corruption, it’s unclear how the country will execute such a feat.

Want to learn more about my Brooks Travelling Fellowship Experience?

Read the Rovang Eye Blog

Subscribe to the Rovang Eye Weekly Newsletter

Listen to the Sundowners Podcast

Follow @sarahmoderne on Instagram

- Trading Economics, “South Africa Unemployment Rate.” Last updated July 31, 2018. Accessed August 29, 2018. https://tradingeconomics.com/south-africa/unemployment-rate ↩︎

- Johannesburg, which is now one of the leading urban, economic powerhouses of Africa, is less than 150 years old. It has the distinction of being a city whose history coincides with the age of photography, and has been extensively documented in the photographic medium. For more on the early architectural history of Johannesburg, see Gerhard-Mark van der Waal, From Mining Camp to Metropolis: The Buildings of Johannesburg, 1886-1940, Pretoria: C. van Rensburg Publications for the Human Sciences Research Council, 1987. ↩︎

- For more on the motivations and goals of my Brooks Fellowship project, you can listen to the pilot podcast of Sundowners (https://anchor.fm/sarah-rovang/episodes/Sundowners-Episode-1-e1s5rq), or read the transcript at https://rovangeye.com/2018/07/28/sundowners-ep-1-conversation-at-a-party/. ↩︎

- For more about the 2015 UNESCO de-listing, and its possible consequences on the ground for these endangered industrial sites, visit my two-part blog on Pilgrim’s Rest. https://rovangeye.com/2018/08/14/there-is-no-law-here-the-pilgrims-rest-mystery-part-1/ and https://rovangeye.com/2018/08/17/pilgrims-rest-part-2/ ↩︎

- Jacques Stoltz, “SA removes sites from the UNESCO world heritage tentative list,” The Heritage Portal, October 25, 2015; originally published July 24, 2015. Accessed August 19, 2018. http://www.theheritageportal.co.za/article/sa-removes-sites-unesco-world-heritage-tentative-list ↩︎

- UNESCO World Heritage Listing of inscribed and tentative sites in South Africa. Accessed August 29, 2018. https://whc.unesco.org/en/statesparties/za ↩︎

- The Old Drostdy Museum in Swellendam. Accessed August 29, 2018. http://www.drostdy.com ↩︎

- According to a “Report on Future Direction for Heritage Conservation in South Africa.” South African government document, October 1994. Architectural archives at the University of Witswatersrand. ↩︎

- Preservation activists are actively addressing the ways in which heritage in South Africa neglects or ignores certain kinds of narratives and agents. As the summary of a 2006 conference on the state of the country’s heritage preservation noted, “State-led commemorations of nationalist achievements and struggle histories have been highly selective, liable to elevate ruling party histories and heroes over others, often ignoring unions, youth or women, and dealing with violence selectively or not at all.“ In other words, even though heritage sites related to the Freedom Struggle and apartheid expand public understanding beyond the kinds of colonial, Eurocentric sites privileged in earlier eras, they too come packaged with their own set of biases and assumptions. JoAnn McGregor and Lyn Schumacher, “Heritage in Southern Africa: Imagining and Marketing Public Culture and History,” Journal of Southern African Studies 32, no. 4 (December 2006): 655. ↩︎

- https://www.debeersgroup.com/southafrica/en/who-we-are/de-beers-in-south-africa/kimberley.html ↩︎

- Nelson Mandela explains the organization of the compounds by tribes this way: “The mining companies preferred such segregation because it prevented different ethnic groups from uniting around a common grievance and reinforced the power of the chiefs” (Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom, Chapter 9). By contrast, signage at Kimberley gives an explanation of the compound system that does not explicitly mention race: “Throughout the 1870s, theft and illicit diamond buying (IDB) was a major concern among claim-holders. Stricter controls and searching systems were introduced, which paved the way for the closed compound system in 1885.” At Cullinan, the given explanation reads: “Due to internal fighting between the different ethnic groups the mine split the shifts along ethnic groups and accommodated them in compounds according to ethnic groups.” ↩︎

- http://www.newtown.co.za/heritage/view/index/workers_museum ↩︎

- Heritage Monitoring Project. “Our vanishing heritage – South Africa’s top ten endangered sites 2016.” The Heritage Portal, September 22, 2016. Accessed August 19, 2018. http://www.theheritageportal.co.za/article/our-vanishing-heritage-south-africas-top-ten-endangered-sites-2016 ↩︎

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top