-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Soundscapes of Industrial Heritage

This month, in lieu of a traditional blog post, I am submitting an “audio post” in the form of a two-part podcast. The “Sundowners” podcast that my partner John Golden and I started in July 2018 has been a way to keep friends and family apprised of my Brooks travel, and to workshop ideas that eventually make their way into this SAH blog series.1 You can access this month’s special two-part episode by clicking the links below, or by searching for Sundowners wherever you typically download your podcasts. Below the links, you’ll find a complete transcript of both episodes, including references and supplementary visual material.

Part 1: Sounding Industrial Places

Sarah Rovang: Hello, and welcome to a special two-part episode of Sundowners. You’re listening to part one, Sounding Industrial Places. I’m Sarah Rovang, the Society of Architectural Historians' 2017 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellow. As usual, I’m joined on this podcast by my spouse and sometime traveling companion, John Golden. Hi, John.

John Golden: Hi, Sarah. It’s good to be here. I like to call myself the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellow’s Fellow. Anyway, if you've been following this podcast, you know that it’s usually structured as a conversation.

SR: But today we’re doing something a little different—this episode will unfold as a spoken word essay, soundtracked by many of the ambient and interpretive soundscapes I’ve encountered during my travels. John has offered to provide another voice as part of this essay, and do a little voice acting, which you’ll hear in a minute.

JG: And this two-part podcast will double as your monthly blog post for the Society of Architectural Historians, right?

SR: Yes, exactly. So, if you want to read a written transcript of this podcast along with supplementary visual materials, please go to SAH.org, where there’s a link to the Brooks blog on the home page. You will also be able to find footnotes and reference materials there, along with more complete descriptions of the various sound clips we’ll be playing throughout both episodes.

JG: As a bit of background for those new to the podcast, I traveled with Sarah in Chile, Japan, and South Africa for the first half of her Brooks Fellowship during 2018. Since then I’ve been back home watching the dogs while she continues her travels abroad. So we’re recording this via Skype—my audio is captured by a nice mic, and hers is coming through AirPods. So that explains the difference in audio quality. Anyway, in these two episodes, we’ll be placing particular emphasis on the places that Sarah has traveled solo in Europe since January.

SR: In part one, “Sounding Industrial Places,” we’ll talk about the soundscapes of industrial heritage, how sound impacts our experience of architecture, and how we can understand the different types of sound we might encounter at an industrial heritage site.

JG: In part two, “Listening to the Industrial Past,” we’ll talk about what it means to hear industrial heritage sites as contemporary listeners, and how sound can be effectively curated and deployed as part of a public history experience.

SR: So put on a pair of stereo headphones, and get ready for this special extended two-part episode on architecture, sound, and industrial heritage.

Intro Music: The Limiñanas, “Tigre du Bengale - Instr.,” The Limiñanas, Trouble In Mind Records, LLC, 2010.

SR: Last month, I made a journey to the coal mining landscape of Wollonia in Southern Belgium. Here, four nineteenth-century coal mines share a UNESCO inscription. Upon arriving at the Bois du Cazier, a mine about one and a half hours South of Brussels, I picked up an audio guide.

The most distinctive architectural feature of the Bois du Cazier site is the mining headgear, marking the shafts where miners would descend far below the surface of the earth. The two towers were nicknamed “les belles fleurs” (the beautiful flowers). In addition to the headgear, the administration buildings and several of the processing and engineering structures have also been preserved and reused as interpretive sites and museum spaces. Several memorials commemorating the tragedy of August 8, 1956 also exist on the site, such as the mural seen here.

JG: I imagine that by this point in your stint as the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellow, you’ve listened to your fair share of audio guides in all kinds of industrial heritage places.

SR: Yes, and I’ve heard a lot of different approaches. This audio guide though was a little different. Instead of the omniscient third-person narrator, you know, the one who sounds like this...

JG (voiceover): On your left, you will see the remnants of a 1895 coal shaft. Note in particular the craftsmanship of the Flemish brickwork.

SR: This one featured two voice actors, playing the roles of Luigi and Monica—a former coal miner and his sister. It was an interesting idea and surprisingly effective. In the story created by the guide, the character of Luigi was returning to the site for the first time since a tragic accident in 1956. This catastrophic event claimed the lives of over 250 miners at the sites, many of them Italian immigrants like Luigi and his family. The first few stops on the audio guide feature Luigi reacting to the site’s transformation from working mine to touristified industrial heritage site.

JG (voiceover): It’s quiet now... you can hear the birds chirping. It’s so peaceful, and so nice. How will people ever know what the mine was actually like? How will they know what that day was like... the day of the accident?

SR: This commentary was some of the first that I’ve heard to acknowledge how industrial places change once they are transformed from active, working sites into curated heritage sites for public use. Beyond that, the audioguide addressed the idea that this transformation is not limited purely to the visual component, but to the complete sensory experience.

JG: How did that change the way you were interacting with this particular site?

SR: Luigi’s comments prompted me, once I was done with the audio guide, to listen more consciously as I explored the site. For example, later in the afternoon, I climbed one of the former slag heaps at the site, which today are laced with trails. Besides the occasional shout of kids playing soccer in the distance, or the roar of a jet overhead, the only sounds I could hear were those of birds chirping and the leaves of new growth-trees rustling around me.

Sound Clip: Birdsong at the Bois du Cazier Slag Heap, Bois du Cazier UNESCO Site, Belgium, February 27, 2019.

Today, the former of slag heaps of the Bois du Cazier are covered by new growth forest and feature a network of popular hiking and bike trails.

SR: The process of noting and recording sounds in the various places I’ve visited has given me new tools to engage with a site. As an architectural historian with only a few years of studio training and a graduate education in an art history program, I usually rely on visual perception in making sense of an architectural space.

JG: Why did you choose to focus on sound specifically though for this project?

SR: Well, I didn’t pick sound as an aspect of this study because I’m a gifted audio engineer, or because I’m even especially attuned to sound. I guess I chose to focus on sound for two reasons: the first was aspirational. The only way I was going to get better at listening was if I actually practiced.

JG: And the second?

SR: The second was because: of all of the other senses we engage when we explore a space, sound, besides sight, is the sense most transmissible through digital media. I might not be able to share with you the chill of a mercury mine in Slovenia, or the chocolatey smell near a cocoa factory in the Netherlands, but I can upload a relatively high-fidelity audio recording of both of those places and at least give listeners an approximation of what those sites sounded like. And through that, perhaps bring our listeners a different impression of these industrial heritage spaces.

Sound Clip: Recording of Swedish pop music at the Norrköping Arbetets Museum (Museum of Work) in Norrköping, Sweden, March 13, 2019.

SR: I want start then today, by talking briefly about what kinds of sounds we might hear at an industrial heritage site.

JG: Right, let’s run through a few examples. To start with, as at any tourism site, you’re probably going to hear the sounds of other people at the site. There might be conversation, footsteps, or the sounds of other visitors engaging with the different interpretive displays or activities.

Sound Clip: A field trip at the M/S Maritime Museum In Helsingør, Denmark, March 21, 2019.

A group of young visitors explores the M/S Maritime Museum In Helsingør, Denmark, designed by the Bjarke Ingels Group (completed 2013). The museum is situated within a former dry dock.

SR: Depending on whether the site is outside or not, there might be natural sounds, created by weather events, flora, or fauna.

Sound Clip: A flock of chickens at Skansen, an open-air living museum in Stockholm, Sweden, March 9, 2019.

Opened in 1891, Skansen is the oldest open air museum in Sweden. The architectural collection includes vernacular structures of the indigenous Sami people, farmsteads from various eras and regions in Sweden, along with civic buildings, churches, and other structures. The scene with the chickens seen here is from a townscape with structures dating from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

JG: There will probably be some incidental sounds. Depending on the site’s location, there might be the sound of a plane passing overhead, or of car traffic...

Sound Clip: Car traffic and construction at the former industrial site NDSM in Amsterdam, Netherlands, Feburary 22, 2019.

Previously one of the largest shipyards in the world, NDSM (Nederlandsche Dok en Scheepsbouw Maatschappij) neighborhood in Amsterdam is today an artist community. Recent development and gentrification have changed the soundscape of the site—construction and traffic sounds are omnipresent.

SR: Or for an indoor site, maybe the roar of the ventilation system in the background.

Sound Clip: HVAC Sounds in a gallery at Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art in Cape Town, South Africa, August 30, 2018.

Designed as a “separate architectural universe,” the gallery space of Zeitz MOCAA resembles a convention white cube format, in stark contrast to the cathedralesque core space. See my SAH blog post on adaptive reuse in Johannesburg for more on Zeitz MOCAA.

SR: In addition to these incidental sounds, there is the whole range of sound that has been curated as part of the visitor experience—what we might call intentional or interpretive sound. The first and most obvious part of the interpretive soundscape is one we’ve already mentioned—the audioguide or audio tour. As we move through the site listening, that audio narration becomes part of our sound experience of that heritage space.

JG: And depending on whether that guide is transmitted through headphones, or the single-speaker model where you hold the guide up to one ear, the audioguide may or may not make it more difficult to hear and notice other sounds.

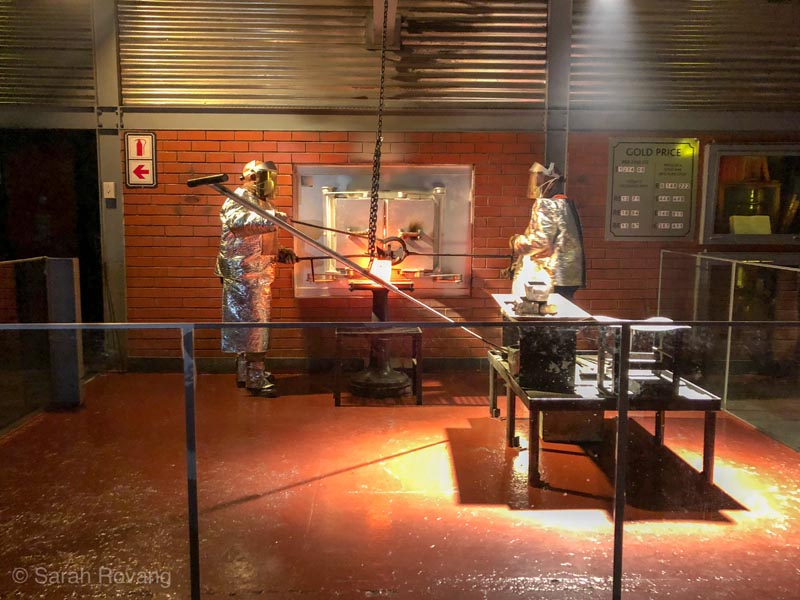

SR: Or, the audio narration might be a shared experience, such as this voiceover at a gold-pouring demonstration at the Gold Reef City theme park in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Sound Clip: Gold pouring demonstration at Gold Reef City theme park in Johannesburg, South Africa, July 25, 2018.

Gold Reef City is a theme park and casino complex located adjacent to the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg, South Africa. Built directly on top of a former gold mine, historic gold mining has been incorporated into the theme park’s attractions. In addition to touring the uppermost level of the old gold mine and a small mining museum, visitors can witness a demonstration of “gold pouring” (which, perhaps unsurprisingly, does not feature real gold).

JG: But there are other types of sounds that are used in an interpretive and intentional capacity to shape the visitor experience of a space.

SR: At an industrial heritage site, we might hear the sounds of created by operational machines onsite, such as this seventeenth-century windmill turning at Zaanse Schans in the Netherlands.

Sound Clip: The operation of a flour-grinding windmill at Zaanse Schans, Netherlands, February 19, 2019.

One of several operational windmills at Zaanse Schans, this one still grinds flour using a mill stone. For more about the architecture of Zaanse Schans, refer to my SAH blog post on European architectures of wind and water.

JG: Or, to give a more contemporary example powered by electricity, this industrial cotton loom at the Museum of Industry in Ghent, Belgium:

Sound Clip: A contemporary industrial cotton loom at the Museum of Industry in Ghent, Belgium, February 24, 2019.

A docent at the Ghent Museum of Industry (MIAT) operates the contemporary industrial cotton looms shown here as part of a permanent installation that illustrates the complete process through which raw cotton is transformed into consumer-ready woven textiles. The operator wears ear protection, as a single loom can generate up to 90 decibels of noise, which is the equivalent of a power mower, or an airplane one mile away. The museum space was originally a textile factory, and the demonstration looms operate in an acoustical condition similar to those in which they would have been heard when the factory was still in business.

SR: We might also hear recorded sounds, played on loudspeakers, through sound cones, or other sound transmission devices. Back at the Bois du Cazier, there was also a recreation of a mine gallery, or tunnel, complete with an atmospheric sound installation.

Sound Clip: An audio recreation of a mine gallery at the Bois du Cazier in Belgium, February 27, 2019.

An above-ground recreation of a mine gallery at the Bois du Cazier mine in Belgium, complete with atmospheric acousmatic sound recording.

JG: And all of these sounds, whether recorded or live, intentional or incidental, interact with the spaces where they are generated. Broadly speaking then, you can say that sound activates space.

SR: Although, theoreticians of sound sometimes argue whether the sound component of a place can be separated out from the holistic impression of space we get as embodied beings.2

JG: So in other words, sound is just one of many non-visual sensory inputs that our bodies receive while exploring an environment—there’s the temperature of the space, the feeling of the materials, the smell. And so you could say that it’s hard to isolate just the sound from all the rest of that experience?

SR: Exactly. And I do believe that sound is part of a more complex, emergent phenomena that, with those other senses, forms our overall experience of a space. But I also think that by considering sound in isolation, we can still learn new things about the built environment, which is—as an architectural historian—ostensibly my aim.

JG: So, how can we think about the soundscape of an industrial heritage site more concretely?

SR: Well, the term “soundscape” was coined in the 1960s by R. Murray Schafer, a composer and audio ecologist. Because of Schafer’s background, much of sound studies has its origins in the environmental movement.

JG: Many of the first works by Schafer and his followers focus on the ecological aspects of sound, using terms drawn from environmental studies, such as the “overpopulation of sound.”3

SR: Or even just think of the title of Rachel Carson’s famous book Silent Spring. Soundscapes were used as a way of understanding changing global ecology. The decline or extinction of certain species could be observed through their absence from the soundscape.

Sound Clip: Wilderness National Park, Wilderness, South Africa, August 13, 2018.

JG: Schafer’s pioneering work on sound has given us many of the terms that scholars of sound still use to describe the makeup of a soundscape.

SR: We’re not going to go through Schafer’s full theory here, but there will be links on the SAH website where you can learn more. (See Further Reading list below.)

JG: As more scholars continued to contribute to the emerging field of sound studies, certain critiques developed of Schafer’s original idea of the soundscape.

SR: One of these was that Schafer’s soundscape seemed to be a kind of acoustical dataset—the net sum of the sounds in a place. For cultural historians, this presented a problem. They argued that listening, like seeing, is shaped by cultural expectation. So, some scholars reformulated the idea of a soundscape to include that element of culture. For instance, French historian Alain Corbin believed that:

JG (voiceover): Like a landscape, a soundscape is simultaneously a physical environment and a way of perceiving that environment; it is both a world and a culture constructed to make sense of that world.4

SR: We are going to be coming back to this idea in part two, but for now, just keep this in the back of your minds—this notion that sounds are inseparable from all the cultural baggage they carry.

JG: Now let’s switch gears for a second and talk about the intersection of sound and architecture, in particular the idea of “spatialized sound.”

SR: To illustrate this idea, we’re going to do a little experiment. I’m going to play the same music clip three times.

Music Clip: 03 Gymnopédie No. 2 Lent et Grave, composed by Erik Satie, c. 1888.

SR: And here's the second version...

Music Clip cited above, overlaid with Sound Clip: Footsteps in the Atacama Desert near Humberstone nitrate mine, Chile, December 11, 2018.

SR: And finally here’s the third...

Music Clip cited above, overlaid with Sound Clip: Footsteps in the Musée des Arts et Métiers, Paris, France, February 13, 2019.

JG: Which of those three recordings called up an image of a place? Probably the second two, right?

SR: And how did the auditory quality of those footsteps affect the way you imagined the space? The first recording, I created while I was walking through the desert landscape around nitrate mine at Humberstone in Chile. And in the second, I was walking across a creaky wooden floor at the Arts et Métiers Museum in Paris.

The two very different built environments heard in the preceding sound clips. Above, Humberstone nitrate mine in Chile and below, the hall of machines at the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris, France.

JG: The echos and reverberations, along with the human element of the footsteps naturally creates a sense of space in addition to the musical component.

SR: And what kinds of acoustical qualities do we associate with industrial heritage sites? These come directly from the architectural form and materials of the site.

JG: Obviously not all sites are the same, but many industrial places are characterized by large, open spaces—the rational and open factory floor, the cylinder of a former gas tank, or the broad sprawl of an airplane hangar.

SR: In addition, particularly in later industrial sites, we start to see the use of new materials in large quantities—concrete, steel, and glass, for example.

JG: These materials and the shapes of the spaces themselves create reverberatory effects.

SR: You hear this art installation at the Färgfabriken contemporary art museum in Stockholm and you can instinctively know, without any other information, that you’re not listening to, let’s say, a living room full of draperies and overstuffed furniture.

Sound Clip: Sound from a video installation by artist Theresa Traore Dahlberg at Färgfabriken art gallery, Stockholm, March 10, 2019.

Theresa Traore Dahlberg’s “In the Wake of Shifts and Memory” at Färgfabriken in Stockholm. This show stitches together the cultural contexts of Sweden and Burkina Faso, touching on themes of the artist’s transnational identities and more broadly, the legacies of colonial industry in today’s postcolonial hightech production practices. The former factory structure of Färgfabriken was renovated in 2011 by Petra Gipp Arkitektur, who describes the building as an “archive,” encoding layers of time through the building’s various uses over the past century as ammunition factory, paint factory, and art museum.

JG: So now that we’ve established what a soundscape is and how it might interact with the architecture of a space, let’s talk a bit more about how we might categorize sound at a heritage site.

SR: We’ve mentioned the difference between incidental and interpretive sounds already. The next key feature we will address is the source of sound—is it created by something live on the site that we can see and identify, or is it being piped in?

JG: Sound theorists have used the term acousmatique, or acousmatic, to refer to sounds whose sources can not be seen, such as loudspeakers or any other similar sound transmission device.

SR: The term derives from the Greek term, akousmatikoi. This referred to certain students of the mathematician Pythagoras, who, as the story goes, had to sit behind a screen and just listen without actually seeing the teacher.

JG: For some sound theorists, using a loud speaker is the modern equivalent of putting a screen between an orator and the audience.5

SR: Acousmatic sounds can serve several purposes in a heritage context. They can reanimate the site through the addition of sound that was historically accurate to that space—for instance, here in this recording of the Norrköping Museum of Work. The Museum of Work is located in a former textile factory, and this sound installation, played in a small, enclosed room, is meant to simulate both the quality and the volume of the industrial textile machines that would have been used in the space during the mid-twentieth century.

JG: Don’t worry, we turned down the volume for the podcast version!

Sound Clip: Textile factory volume demonstration, Norrköping Arbetetsmuseum (Museum of Work), Norrköping, Sweden, March 13, 2019.

Another museum in a former textile factor, the Norrköping Museum of Work (Arbetetsmuseum) in Sweden is notable for the focus that it places on the lives of women workers, and issues of unionization, personal liberty, child care, and pay equity. Norrköping boasts one of the best preserved industrial cores in Europe, and the work museum sits at the heart of this waterfront industrial district. Many of the former industrial buildings are now used by the local college for student life and classroom space. The sound installation you can hear in the clip is shown in the first image above.

JG: Acousmatic sound might also take the form of spoken narration, such as voice actors or recorded oral histories telling human stories, giving voice to certain experiences. This might also include other non-industrial sounds, such as the actions of daily life.

SR: For instance here, at the pulperia, or general store, of Humberstone nitrate mine in Chile, an acousmatic sound recording evokes the sounds and the dialog of the fabric shop within the general store.

Sound Clip: Acousmatic sound representing the action of a fabric shop in the pulperia, or general store, at Humberstone nitrate mine, Chile, December 11, 2019.

The pulperia, or general store, supplied everything nitrate miners and their families needed for daily life, because the location of remote mines like Humberstone made regular travel to larger port cities impossible. The scale and complexity of this structure testifies to the prominence of the pulperia in the daily life at a salitrera (Chilean nitrate mine). Miners were also frequently paid in tokens rather than actual currency, which were only exchangeable for goods at the general store.

JG: Another category of the industrial heritage acousmatique is that of art sounds, installations meant not to recreate the past, but to engage the space in a new auditory way.

SR: Here’s an example from Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art in Cape Town where the recording of a unaccompanied choral piece is projected into the museum’s core space, a vast latticework of concrete grain silos partially carved away to create a new public space for the museum.

Sound Clip: Acousmatique site-specific art installation at Zeitz MOCAA, Cape Town, Johannesburg, August 30, 2018.

The core space of Zeitz MOCAA, which spans a carved-out atrium comprised of the interstitial space between the old elevator building and silo building, is animated by the addition of sound installations, which magnify the cavernous feeling of the space.

SR: Sometimes, acousmatic sounds are used metonymically, or as smaller pieces that represent or stand in for the idea of “industry” or the “industrial revolution” as broad abstract concepts.

JG: We’ll be talking more about this potentially problematic approach a lot more in part two.

SR: Yes, we’ll be building on the ideas and concepts that we discussed today, and returning to this critical notion that listening is not a neutral act.

JG: It might seem like an obvious fact, that the way we hear and make sense of sound is deeply influenced by culture.

SR: Many of us, particularly those in predominantly visual fields like art and architectural history, understand that a photograph does not 100% represent “reality”.

JG: In other words, the lived moment seemingly preserved in a photograph is gone, irrecoverable, and the image we see in a photograph is not a direct reflection of reality. We’ve been taught this, and most of us regard photographs with a bit of suspicion, knowing that we are always getting a cropped or Photoshopped fragment, mediated by the intentions of the photographer, edited to make it a hit on Instagram.

SR: While this is also true of sound recordings, I think there’s less awareness of them as incomplete records of a moment in time and space. We treat acousmatic sounds as acoustical facts rather than part of a multi-sensory, interpreted heritage experience. Frequently, we don’t recognize the way in which we, as listeners, are listening in ways that are culturally contingent and colored by our own preconceptions about industry and the very conditions of modernity.

Sound Clip: Acousmatic sound of a spinning mule jenny at the Ghent Museum of Industry, Ghent, Belgium, February 24, 2019.

JG: That wraps up the first part of our two-part series. Part 2: Listening to Industrial Spaces is available wherever you get your podcasts.

SR: Script, editing, and producing for this episode by me, with additional editing assistance from John Golden. All sounds in this podcast were recorded by me in my capacity as H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellow unless otherwise noted. You can see more visual material and read the complete transcript of this episode at SAH.org.

JG: Our theme music is by The Limiñanas. And it wouldn’t be an episode of Sundowners without our signature sign-off.

SR: Happy trails, listeners.

Exit Music: The Limiñanas, “Tigre du Bengale - Instr.,” The Limiñanas, Trouble In Mind Records, LLC, 2010.

Part 2: Listening to the Industrial Past

Sarah Rovang: Hello, and welcome to a special two-part episode of Sundowners. I’m Sarah Rovang, the Society of Architectural Historians’ 2017 H. Allen Brooks Traveling Fellow. This part is called Listening to the Industrial Past. If you haven’t yet heard Part 1: Sounding Industrial Places, I suggest you go back and do so now. Once again, I’m joined by my spouse and sometime traveling companion John Golden. Hi, John.

John Golden: Hey, Sarah. It’s good to be back.

SR: In this second part, we’ll be talking about the ways in which cultural conceptions of industrial sound have changed over time and how, as contemporary listeners, we can better understand industrial heritage by learning to listen with a contextual awareness of the past.

JG: We’ll also talk about the ways in which curators and museum professionals can use sound at industrial heritage sites to help audiences experience these sites in new and unfamiliar ways. So let’s jump right in.

Intro Music: The Limiñanas, “Tigre du Bengale - Instr.,” The Limiñanas, Trouble In Mind Records, LLC, 2010.

SR: In the previous episode we talked about how, within the field of sound studies, some cultural and social historians critiqued the initial formulation of what we call a “soundscape.” These historians argued that a soundscape should include both the culture of listening and understanding as well as the actual sounds themselves.

JG: As a refresher, scholar Alain Corbin (paraphrased here by scholar Emily Thompson) defines a soundscape as: “simultaneously a physical environment and a way of perceiving that environment; it is both a world and a culture constructed to make sense of that world.”6

SR: So let’s break that definition down into its two parts and address each in turn: first, the environment, or the sounds themselves, and second, the way in which we as listeners understand and make sense of that environment.

Sound Clip: Corazza Monoblock Machine at the Museum of Industry, Bologna, Italy, February 2, 2019

The clip heard here is from the Museum of Industry in Bologna, an institution which is notable for its adaptive reuse of a former brick and terra cotta factory. Seen here is the kiln, which has been transformed into interpretive space on the museum’s ground floor. The museum also owns an impressive collection of functional machines from Italy’s post-WWII manufacturing boom.

JG: The whir of a motor, the whistle of a train, the clacking of a loom, the shudder of a lift pulling up raw ore from deep within a mine—these are the sounds that we typically associate with the Industrial Revolution.

SR: Today, we live in a built environment where sound is heavily engineered. Acoustical designers can use advanced materials and spatial forms to shape the soundscape of the buildings where we live, work, and play.

JG: But industrial sounds such as those I just mentioned predate the advent of modern sound engineering.

SR: In the groundbreaking book The Soundscape of Modernity, cultural historian Emily Thompson explored the ways in which during the twentieth century, sound was “gradually dissociated from space until the relation ceased to exist.”7

JG: In other words, the new field of acoustical engineering tried to eliminate the reverberatory qualities of architecture that used to so directly link sound and place. And in addition, many of us now listen to music or podcasts like this one on headphones, further divorcing the source of sound we hear from our immediate environment.

SR: Yeah, it’s a pretty radical contrast with some of the very site-specific sounds I’ve encountered during my travels. One of the most significant revelations of my time in Europe has been how loud industrial machinery could be even in the era before steam power and electricity. A windmill like the one we heard in part one at Zaanse Schans, or even a hand loom, can produce a staggering amount of noise.

Sound Clip: The operation of a flour-grinding windmill at Zaanse Schans, Netherlands, February 19, 2019.

JG: But the scale and quality of that industrial noise changes significantly in the nineteenth century, when both the machines themselves, and the buildings that contain them, begin to have more metallic components and harder surfaces. A wooden loom in a wooden and stone room, however loud, sounds radically different from a metal loom in reinforced concrete room. Similarly, a nineteenth-century water-powered rice pounder made from stone and wood...

Sound Clip: Water-powered rice pounder at Shuiseikan UNESCO World Heritage Site, Kagoshima, Japan, September 19, 2018.

JG: (yelling) Sounds very different from a mid-twentieth-century concrete hydroelectric dam!

Sound Clip: Shimizusawa Hydroelectric Dam, near Yubari, Japan, September 13, 2018.

Though I wasn’t able to access the Shimizusawa Thermal Power Plant when I visited in September, I did get some impressive footage of the nearby hydroelectric dam, along with an impromptu self-guided tour Japan’s postindustrial and economically depressed Yubari region on Hokkaido.

SR: So, much of the twentieth-century desire to eliminate reverberation and echoes had to do with the ways in which architectural sounds changed during the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century. And with the advent of steam power, and eventually electricity, machines got larger and more powerful. And building surfaces became harder and interacted with those machine sounds in new ways.

JG: This change in the acoustical qualities of industrial architecture came even more to the fore when the architects of the modern movement began using these industrial materials to design “machines for living in.”

SR: For example, this Danish critique of the architecture of the Bauhaus cleverly conflates the visual reflections created by all those new hard surfaces with the auditory equivalent:

JG (voiceover): “In acoustic terms, the room is like a tin box, each word pounding on the lid, sides and bottom. The glazed area in itself is too big, and light from the lower panes bounces in vicious reflections off the floor and tables and into the eyes, which cannot shield themselves from light coming from below.”8

SR: In the wake of such critiques, the architectural soundscape of the twentieth century became increasingly homogenized and detached from any sense of place. As Emily Thompson puts it:

SR (voiceover): “Clear, direct, and nonreverberant, this modern sound was easy to understand, but it had little to say about the places in which it was produced and consumed.”9

SR: This drastic shift points to the fact that somewhere, between the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, attitudes towards industrial noise and the associated modern spaces where this noise was created, changed.

JG: Which means, to move onto the second part of our soundscapes equation, the culture of listening must have changed as well.

SR: As many scholars of sound and industry have noted, for the nineteenth-century listener, the sound of modern industry was widely regarded as positive, and synonymous with technological progress. James Watt, the British inventor of the steam engine, once remarked upon the connection between sound and industry, noting that:

JG (voiceover): “I once adjusted the machine so that it made less noise. But the owner cannot sleep, when he cannot hear its rage. People seem to join the power of the machine because of the noise. Modest skills are neither recognized by humans nor machines.”10

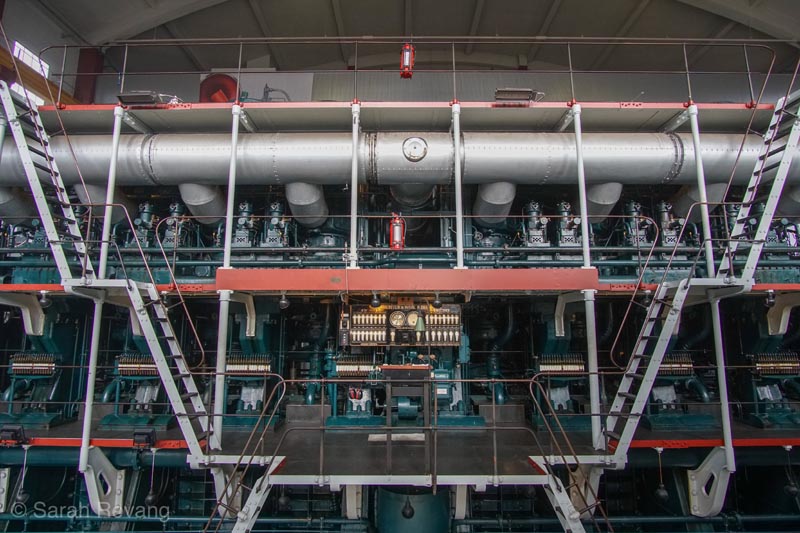

Sound Clip: Diesel engine demonstration at DieselHouse, Copenhagen, Denmark, March 17, 2019.

DieselHouse Museum in Denmark, Copenhagen. This massive Diesel engine built by Burmeister & Wain was the largest in the world for more than a decade after its construction in 1933. The building that houses it was part of the H.C. Ørsted Værket company and was built in anticipation of this massive generator in 1932. The engine supplied much of Copenhagen’s energy demands for many years and served as a backup generator until the early 2000s. It is still operational today, but is only used for educational and demonstration purposes, such as the one in the sound clip heard here.

SR: For Watt, industrial noise was a signifier of power and productivity. And even though this noise might have been unpleasant or undesirable for those living and working within earshot of factories, mines, and mills, little was done during the nineteenth century to mitigate that noise. Environmental historian Peter Coates even likens the expansion of noise to notions of manifest destiny and cultural imperialism:

JG (voiceover): “An onward-marching Euro-American civilization filled the great auditory void of the wilderness with sonic meaning...To the early nineteenth-century modernist ear, mechanical sounds and the noisy bustle of commerce bespoke prosperity. Quiet was synonymous with indolence, backwardness, and stagnation. For the nineteenth-century advocate of industrial progress, a place where you could hear the grass grow (or only the cartwright's mallet and the horse's whinny) was not somewhere you wanted to be.”11

Sound Clip: Diesel engine demonstration at DieselHouse, Copenhagen, Denmark, March 17, 2019.

Sound Clip: Rooster and chickens in the yard of a house in the company town of Crespi d’Adda, UNESCO World Heritage Site, January 29, 2019.

Since the cotton mill at Crespi d’Adda near Milan, Italy is no longer active, much of the company town now has a rural and pastoral feel, amplified by the rustic soundscape of chickens and gardening activity.

SR: In other words, while contemporary listeners might call industrial sounds “noise pollution” and find solace in a soundscape of nature uninterrupted by human activity, listeners of 150 years ago would have had very different associations with those same auditory events.

JG: As a result, when we (as contemporary listeners) hear interpretive sound at an industrial heritage site, even if those sounds are historically accurate to the site and space, we are bringing a different set of cultural expectations and beliefs to our listening experience.

SR: In addition to cultural changes in how we listen, there are also the physical changes and acoustical changes that happen when industrial spaces are transformed from places of active work into heritage sites.

JG: Spaces are renovated to accommodate the flow of visitors, new structures are added, and machinery is cleared away to expand museum space.

SR: At the same time, the original architectural fabric may change over time due to weathering and decay. The soundscape of the Humberstone nitrate mine in Chile, for example, is now typified by rusted sheet-metal cladding that makes a very distinctive sound in the wind:

Sound Clip: The whistling and creaking of rusted sheet metal in the industrial sector of Humberstone nitrate mine, December 11, 2018.

The Humberstone Engine House, part of the salitrera’s industrial sector where the above sound clip was recorded. As the sheet metal cladding on these industrial structures has rusted and decayed, new sound elements emerge.

JG: At many sites, nature has been allowed to reclaim former industrial landscapes, and birdsong and trees in the wind like you heard at the Bois du Cazier mine in Belgium have taken the place of active machinery.

Sound Clip: Birdsong at the Bois du Cazier Slag Heap, Bois du Cazier UNESCO Site, Belgium, February 27, 2019.

SR: So, knowing that the physical environment of a working nineteenth-century industrial site AND the culture of listening around it are both unrecoverable, how should curators and museum professionals approach the element of interpretive sound at such a site?

JG: And further, what can interpretive sound add to an industrial site, knowing that a complete recreation of historic sound, and the historical culture of listening to that sound, are lost to the past?

SR: To try to answer that question, I want to focus in for a few minutes on the most frequent interpretive sound strategy I’ve observed across the globe: adding a recording, played over loudspeakers, of a period-appropriate industrial machine in action.

JG: This goes back to the idea of acousmatic sound we talked about in part one: that particular category of interpretive sound where the original source of the sound is hidden or dissociated from the listener. Here’s an example of this kind of an acousmatic recording being played at a heritage site:

Sound Clip: Acousmatic sound of a spinning mule jenny at the Ghent Museum of Industry, Ghent, Belgium, February 24, 2019.

SR: The sound you heard just now is from a recording at the Museum of Industry in Ghent of a spinning mule jenny.

JG: This is a vast textile machine that spins raw fibre into thread in mass quantities. The automatic, or self-acting version of the machine, was invented in the 1820s. These machines were often operated by children before the eventual introduction of child labor laws.

SR: The museum in Ghent has a rare example in its collection, presented as the single artifact in a long, custom-built space. At one end of the darkened room, archival film footage plays, showing child workers using one of these machines.

The permanent exhibition on the top floor of the Ghent Museum of Industry (MIAT) is comprised of a series of single-room exhibitions that flow in chronological order, each in separate, enclosed structures scattered across the open daylight factory floor. One of these room-sized displays is the darkened room that houses the spinning mule jenny, one of the rarest and largest artifacts in the museum’s collection.

JG: This museum in Ghent is located in a former textile factory, where such a device would have been operated. The interaction between the space, the machine artifact, the film, and the sound, creates a complete sensory experience.

SR: A few days later, I went to the House of European History museum in Brussels. In the part of the general exhibition devoted to industry, I was surprised to hear this sound again:

Sound Clip: Acousmatic sound of a spinning mule jenny at the Ghent Museum of Industry, Ghent, Belgium, February 24, 2019.

SR: But in this second experience, the acousmatic sound of the spinning mule jenny was disconnected from any signification of what created that sound. Gazing at industrial artifacts from across Europe, some of which did have to do with textile manufacture, I realized that this sound was being used metonymically, or symbolically.

JR: So, in other words, by using this distinct sound in an exhibition meant to encompass the entire European Industrial Revolution, this recording of the spinning mule jenny was meant to signify a lot more than just a single advancement in textile machinery—it was standing in for broader abstract concepts like mass production, rationalization, and the dehumanization of the factory worker.

SR: There’s nothing wrong with using sound to evoke a feeling or idea. Many industrial sites use sound in precisely this way. What I think can be problematic though is the use of sound in a way that conforms to visitor’s preconceptions.

JG: Ideally, a public history experience prompts us to confront the past in a new way, causes us to examine our entrenched beliefs and maybe revise them.

SR: The issue I have with so much acousmatic sound used at industrial heritage sites is that it functions as glorified audio set dressing. Take the M/S Maritime Museum in Denmark, for example.

JG: This building has gotten a lot of press because it was designed by the famous contemporary Danish architect Bjarke Ingels, and cleverly reuses the underground site of a former shipyard. The installation itself presents a highly produced but very general view of Danish maritime culture. The exhibit is soundtracked by old film footage and sound effects:

Sound Clip: Acousmatic maritime military soundscape from the M/S Maritime Museum, Helsingør, Denmark, March 21, 2019.

A slick, high production-value historical display at the M/S Maritime Museum In Helsingør, Denmark, which opened to much acclaim in 2013. The theatrical polish of the permanent exhibition rivals that of the architecture, an award-winning Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) design sunk below the earth in a historical dry dock in the Helsingør shipyard.

JG: Within the model of museum as entertainment, the richness of the Maritime Museum’s soundscape creates atmosphere and enhances the overall museum environment.

SR: But I would argue that creating atmosphere is not exactly the same as historical storytelling. Catering to stereotypes of seafaring culture, these sounds effectively perpetuate our preconceptions rather than prompt us to examine them. For that reason, some of the auditory interventions I’ve found the most enlightening and rewarding in industrial heritage spaces are those that strive towards art over historical accuracy.

JG: Sound installation art broadens the range of visitor experiences in an industrial site and might even inspire us to look closer, in addition to listening closer. Take that formative sound art piece by composer John Cage: 4’33”.

SR: In the performance of 4’33”, which can be executed with any instruments and number of performers, musicians are instructed not to play their instruments for the duration of the piece. What is typically at the forefront of such a performance—that is, live music, drops away, revealing instead the incidental soundscape of the performance hall.12 A cough, the rustling of a program, the sound of the ventilation system—all these sound events became part of the piece.

Sound Clip: Visitors being “silent” in a piece by James Turrell called “Open Sky” at the Chichu Museum of Art, Naoshima, Japan, October 10, 2018.

JG: Other more recent examples of sound art engage specifically with industrial heritage. For instance, the work entitled “A View of a Landscape” by artist Kevin Beasley currently at the Whitney Museum in New York.

SR: In this work, Beasley repurposes a twentieth-century cotton gin as a kind of musical instrument, employing this industrial machine for its auditory potential rather than its original intended use of processing cotton fibre. In doing so, Beasley defamiliarizes this potent historical object, bringing to light issues of space, race, power, and industrialization in the American South.

JG: Links to more information and videos of this work can be found as part of the podcast transcript at SAH.org.

SR: I’ve encountered sound installations in a variety of contexts in a number of the industrial heritage sites I’ve visited. For instance, there was this really evocative sound installation by the Belgian artist François Curlet as part of a recent solo show called “Crésus & Crusoé” at MAC’s, or Musée des Arts Contemporains de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles at the Grand Hornu. But before we play you the clip, we need to describe the space.

JG: MAC’s shares its space with the Grand Hornu, an early nineteenth-century Belgian coal mine, which shares its UNESCO listing with the Bois du Cazier, the site we discussed in part 1.

SR: The space itself is pure neoclassical Utopianism. In fact, the architect of the Grand Hornu was very directly inspired by the French architect Ledoux’s plan for the Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans.

The architect of the Grand Hornu, Bruno Renard, was directly inspired by Ledoux’s 1804 book, and the site incorporates many features similar to the Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans. A former coal mine and company town, this site was nearly razed in 1969 to make room for a shopping mall parking lot. It was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2012 and today shares its space with two art museums, in addition to housing office space and serving as an occasional community gathering and theater space.

JG: If you have no idea what we’re talking about, remember that you can see all the visual material by going to SAH.org and navigating to the Brooks blog from the homepage!

SR: Anyway, so imagine this planned community, which centers around an oval shaped center courtyard. All of the structures are really monumental and quite imposing.

JG: And one side of that oval, the former administration building, has been converted into this art museum, MAC’s, and several new, very contemporary-looking structures have been added.

The blend of old and new construction at MAC’s, and the interior gallery stairs where I heard the sound installation that was part of Belgian artist François Curlet’s recent exhibition there.

SR: So it’s in that space where I heard this sound installation piece:

Sound Clip: Acousmatic sound from art installation by François Curlet at MAC’s, Grand Hornu, Mons, Belgium, March 1, 2019.

JG: You’ve got some pleasant harp music, with the occasional bleating sheep in the background.

SR: In this former industrial building, the overall effect upends your expectations of how the space should sound. Hearing this very idyllic and even rural sound collage made me really stop and think about the what expectations and assumptions I had brought with me to this site.

JG: Rather than just reflecting visitors’ preconceptions about industrial spaces back to them, this kind of sound intervention disrupts cliché and stereotype and makes you wonder—what do we really know about the landscape of industry?

SR: At the end of the day, the element of sound at industrial heritage sites is a conversation between museum professionals and listening audiences.

JG: Visitors who are aware that the soundscapes they encounter are not just neutral backdrops have a much greater chance of appreciating the nuances of their public history experience.

SR: And conversely, museum professionals who use sound as an integral interpretive element that transcends the standard soundtrack of industry have a greater chance of communicating the importance of preserving and interpreting industrial places.

JG: Thanks for listening to this special episode of Sundowners. If you enjoyed this and would like to catch up on back episodes, you can search for Sundowners wherever you get your podcasts.

SR: Script, editing, and producing for this episode by me, with additional editing assistance from John. All sounds in this podcast were recorded by me in my capacity as H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellow unless otherwise noted. You can see more visual material and read the complete transcript of this episode at SAH.org.

JG: As always, our theme music is by The Limiñanas.

SR: Happy trails, listeners.

Exit Music: The Limiñanas, “Tigre du Bengale - Instr.,” The Limiñanas, Trouble In Mind Records, LLC, 2010.

Further Reading

Coates, Peter A. “The Strange Stillness of the Past: Toward an Environmental History of Sound and Noise,” Environmental History 10, no. 4 (October 2005), 636-665.

Corbin, Alain. Village Bells: Sound and Meaning in the Nineteenth-Century French Countryside. London: Papermac, 1999.

Fowler, Michael. “On Listening in a Future City.” Grey Room no. 42 (Winter 2011): 33.

Gunderlach, Jonathan. “Exploring a Character-Defining Feature of Historic Places.” APT Bulletin: The Journal of Preservation Technology 38, no. 4 (2007): 13-20.

Schafer, R. Murray. The Tuning of the World: Toward a Theory of Soundscape Design. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1980.

Sterne, Jonathan. The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction. Durham: Duke University Press, 2003.

Thompson, Emily A. The Soundscape of Modernity: Architectural Acoustics and the Culture of Listening in America, 1900-1933. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2004.

Further Listening

Gordon Hempton, “Silence and the Presence of Everything.” On Being with Krista Tippett,original airdate May 10, 2012.

Twenty Thousand Hertz podcast.

“Ways of Hearing,” Showcase podcast by Radiotopia.fm, originally aired Summer 2017.

- Conceived as “conversations architecture, place, and global travel,” “Sundowners” was named for the ritual that concludes the day on an African safari—a practice of gathering with friends and strangers over food and drinks to watch the sunset and reflect on the day. ↩︎

- One of the more prominent scholars to endorse this theory is social anthropologist Tim Ingold. Michael Fowler, “On Listening in a Future City,” Grey Room no. 42 (Winter 2011): 33. ↩︎

- Refer to Raymond Murray Schafer, The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World (1977). For a succinct summary of Schaffer’s work within the context of historical preservation, see Jonathan Gunderlach, “Exploring a Character-Defining Feature of Historic Places,” APT Bulletin: The Journal of Preservation Technology 38, no. 4 (2007): 13-20. ↩︎

- Alain Corbin, as paraphrased by Emily Thompson, The Soundscape of Modernity: Architectural Acoustics and the Culture of Listening in America, 1900-1933 (Cambridge, Mass.; London, England: MIT Press, 2004), 1. ↩︎

- Fowler, “On Listening in a Future City,” 26. ↩︎

- Alain Corbin, as paraphrased by Thompson, 1. ↩︎

- Thompson, 2. ↩︎

- Quote from Danish magazine Kritisk Revy (Critical Review), founded by Poul Henningsen, published 1926-1928; quote as seen at the Danish Designmuseum in Copenhagen, Denmark. ↩︎

- Thompson, 3. ↩︎

- Quote from James Watt (1736-1819), as it appears on the interpretive signage at the DieselHouse Museum in Copenhagen, Denmark. ↩︎

- Peter A. Coates, “The Strange Stillness of the Past: Toward an Environmental History of Sound and Noise,” Environmental History 10, no. 4 (October 2005), 643. ↩︎

- Fowler, “On Listening in a Future City,” 38. ↩︎

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top