-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Mines, Mills, Museums: My Year as a Professional Industrial Heritage Tourist

Sarah Rovang is the 2017 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

My final visit to a UNESCO-listed industrial site as the 2017 H. Allen Brooks Fellow entailed a slippery descent into a dimly-lit fourth-century Roman limestone cavern covered in WWI-era graffiti under the remains of a twelfth-century French abbey in Reims, France. I stood at attention among a couple dozen other tourists and innumerable bottle racks, listening to a dapper company representative explain the manufacture and global distribution of champagne. Our guide explained that even though machines can now agitate champagne so that the sediment of secondary fermentation settles in the neck of the bottle, the best bottles are still turned by hand. I struggled to imagine the carpal tunnel-inducing job of rotating tens of thousands of bottles a quarter turn to the right and an eighth turn to the left every few days. After emerging from the dank of the cellar, the other tourists and I loitered in the slick, contemporary tasting room where there were ample opportunities to purchase a few bottles for the road. Traversing sixteen-plus centuries of architectural history, the whole experience blurred the lines between craft and mass production, heritage and consumerism, local production and global economics. It was a fitting coda to an incredible year of industrial heritage travel.

Underground the Tattinger Champagne House in Reims, France. Above, a sequence of caverns dating to the Roman period. Below, newer tunnels like the one seen here were welcome refuges from the destruction of World War I in northern France. The naturally cool chalk caverns are climate-stable places to store champagne during secondary fermentation and aging.

Revisiting the Public History of Industrial Heritage

Who is industrial heritage for? Nearly every site I visited across fourteen countries and five continents had a slightly different answer to this question, targeting a specific demographic. Spelunking a champagne cave with a slew of monied Anglophone tourists was at one end of the spectrum; lingering in the shadow of a shuttered Japanese coal mine where the only other visitor was a kindly former miner was the other. Throughout the trip, I variously found myself entirely alone, surrounded by locals, or crowded by other international tourists. I encountered aged history buffs, millennial ruin-seekers, field-tripping school children, former industrial workers, family vacationers, even a few kindred scholars of industrial heritage. And each of these groups seemed to be getting something different out the sites they were visiting.

Fellow industrial heritage tourists in Tokyo, Japan; Idrija, Slovenia; Birmingham, England; and Valparaiso, Chile.

Across the board, the most engaging museums and sites were those with a clear conception of who their main stakeholders were and that targeted their public storytelling towards those key groups. The South End Museum in the industrial city of Port Elizabeth, South Africa, is a prime example of a museum predominantly serving a local population. In addition to being an impressive public history record of a once vibrant neighborhood decimated by apartheid, it is an anchor of memory for the surviving diaspora of community members and their descendants. As I wrote shortly after my visit:

This was decidedly not a museum that was out to explain the vast injustices of apartheid to foreign visitors, or even to capture or create some sweeping, master narrative about the legacy of the South End. Instead, it clearly identified the actual and real needs of its stakeholders in the community, and prioritized those, becoming a repository and safe place for individual experiences of dislocation and disenfranchisement. The restorative truth the South End Museum is providing for its community outweighs, I think, the need to cater to outsiders.

The fig tree of the old South End (at far right) is one of the few surviving remnants of the community that used to be there. It now stands at the intersection of two busy highways on the sea coast of Port Elizabeth.

Sites like the South End Museum were less common that those consciously catering to a wider regional, national, or international audience. At the tourist-oriented sites, I was frequently taken aback by how often the tone of interpretation was largely celebratory. Unfettered technological utopianism and “great man” history are still standbys at many former industrial places. Reliance on these tired and problematic tropes always felt like a lost opportunity. Interpretation, after all, has the power to determine whether public audiences experience industrial buildings, spaces, machinery, and processes as cogs within a inevitable march of progress, or as multifaceted cultural products that reciprocally shape nuanced configurations of power, privilege, and technical knowledge.

The tourist-oriented sites and museums that I found the most effective in terms of public storytelling were those that:

- Incorporated architectural interpretation and helped patrons to “read” and understand the built environment of industry. Often, the most vivid and tangible public history experiences were attached to well-preserved architectural landscapes.

The excellent interpretative signage at Humberstone in Chile helps visitors to understand how differences in pay and power were also manifested in the spatial arrangement and architecture of the nitrate mining town. Housing for lower-ranking workers (top two images) possessed less ornamentation and fewer interior rooms than the houses of engineers and administrators (second to bottom), or the house of the mine’s director (below).

- Addressed the tension between the local idiosyncrasies of industrialization and the global and homogenizing forces that shaped industrial sites and their architecture.

The interpretation at the fan-shaped artificial island of Dejima in Nagasaki, Japan, addresses the early global influences on the supposedly “isolated” Edo-era Japanese islands. Dejima, where Dutch traders were allowed to live in exchange for a tribute to the emperor, became an early nexus of international contact and cross-cultural exchanged between Japan and Europe. The restored interiors and high-quality multi-lingual storytelling illustrate the ways in which early Japanese industrialization relied on a unique blend of local artisanal practices and imported technical knowledge.

- Recognized that industrial architecture and technologies are still fundamentally cultural products. For the sites I visited in Europe, this also meant de-centering European experiences and technical knowledge in favor of a more global reading.

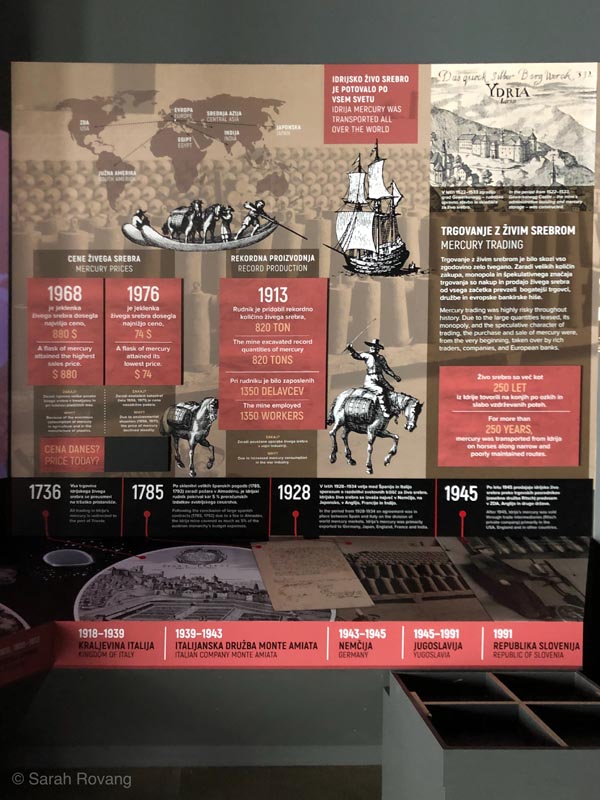

The signature tour of the UNESCO-listed mercury mine in Idrija, Slovenia (above) is complemented by the museum at the restored Hg Smeltery (middle) and the Mestni muzej Idrija (Municipal Museum, below). Both museums compellingly show the role of the Idrija mine as part of a larger network of global trade and political economies.

- Focused more on the lived experiences of a diverse array people rather than the specifics of technical processes, or used technology as an entry point to human experience.

The Ghent Industriemuseum (MIAT Ghent) presents the history of textile manufacture in the northern Belgian city as a series of individual stories, told in Dutch, English, and French (and subtitled in all three). Based on the lives of real individuals, the stories encompass the experiences of factory workers from a variety of backgrounds, engineers, and even a woman factory owner. Presented as well-acted videos, these stories make palpable how the vicissitudes of the global textile industry affected everyday lives.

- Grappled with the aestheticization of industrial ruins and the “dark tourism” aspects of industrial heritage.

The architectural audioguide at Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art in Cape Town, South Africa reveals the complex social history of this former grain elevator-turned art museum. Designed to provide employment for poorer whites in the days before formalized apartheid, this building was part of a structure of economic disenfranchisement for non-white people in South Africa. While architect Thomas Heatherwick’s sumptuous re-envisioning of the elevator and silo spaces sometimes distances itself from the problematic history of the structure, many of the site-specific art installations engage the building’s history and confront the darker aspects of its uselife, and that of the South African industrial landscape at large.

- Brought industrial legacies to bear on the postindustrial present. In other words, these were the sites that acknowledged how the Industrial Revolution, for all of its advancements, is also implicated in enduring consequences of colonialism, slavery, fossil fuels, habitat loss, fanatic nationalism, and modern warfare.

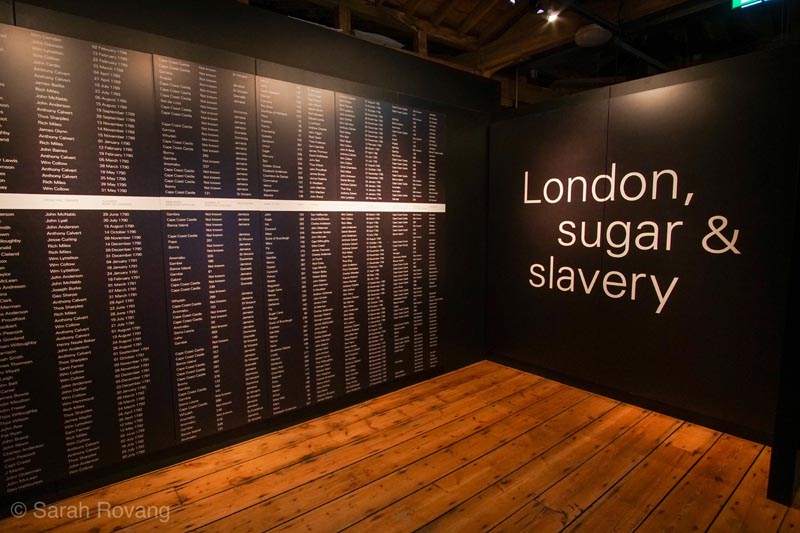

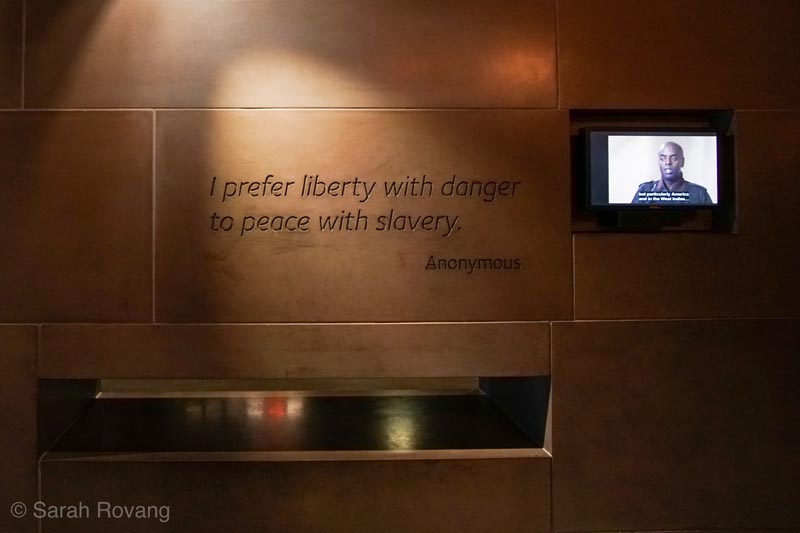

Both London and Liverpool contain numerous historical sites that engage the history of the Industrial Revolution in the U.K. The Museum of London Docklands and the International Museum of Slavery, Liverpool both contend with the ways in which Britain’s industrializing economy perpetuated the North Atlantic slave trade, and the lingering effects of the exploitative trade relationships that the empire forged across the globe.

Go Abroad to Go Broad: Process and Experience

As a fledgling scholar, I fully subscribed to the notion that knowledge production at the Ph.D. level constituted tiny outward pushes in the ever-ballooning sphere of human knowledge. Accordingly, as the Brooks Fellow I expected to travel to new places, conduct research in the field and archives, synthesize my findings with secondary readings, and voila: new architectural history knowledge! And that was precisely how my first weeks in Johannesburg went: devouring the urban history books out of my AirBnB host’s substantial library over coffee, visiting museums and archives or going on walking tours during the day, and then writing up my analysis in the early winter twilight hours. It all felt stable, sustainable, and familiar. And it all immediately fell apart as soon as the road trip leg of my South African excursion began. After the ten-hour drive from Pilgrim’s Rest to Kimberley across a flat desert landscape punctuated only by the occasional factory or ostrich farm, I barely felt fit to locate dinner, much less “produce knowledge.” And given the pace of travel that persisted throughout much of the rest of my fellowship year, I often found myself in a similar position. I had to fundamentally rethink the way I conceived of “creating knowledge” on the road. It was a shift away from the archival research model and towards experiential learning, drawing on my own personal observations for primary evidence.

This process of reorienting to a new way of being in the world, of encountering historical sites and museums across the globe, also came with a corresponding call to reevaluate how I was recording and sharing my experiences.The relative newness of the H. Allen Brooks Fellowship is a double-edged sword when it comes to carving out one’s own place among the pantheon of former fellows. There is not enough institutional memory around this fellowship for its expectations to have ossified in any substantial way. Conversely, the handful of previous scholars seemed like giants as I began my travel year. Indeed, I felt a deep sense of insecurity about the fact that I wasn’t going to fill up whole sketchbooks with immaculate drawings, nor did I have the photographic expertise to capture arresting, print-quality images. Over the course of the year, my photographs did get noticeably better and I grew a little bit less shy about sketching in public, though my favorite drawings tended to be of people looking at buildings rather than the buildings themselves.

But within the first several months, I quickly settled on writing as the main medium for recording my travels, and sharing those meditations with a broader audience. In addition to the monthly SAH blog post, I maintained a weekly newsletter and a weekly podcast co-written with my partner, John Golden. I recorded my daily activities in bullet-form journal entires. I started a personal blog as well, but quickly found that I had overstretched myself. Instead, my daily Instagram posts became the most immediate venue where I processed and shared my experiences. Cumulatively, all these writing practices allowed me to experiment with format, voice, and style. Occasionally, an SAH blog post veered towards the overly academic, and risked coming off as a half-baked journal article. The most successful written pieces were those that started with my own personal experience and direct observations.

For the majority of my time on the road, I was between jobs and cut off from the digital resources of university libraries and JStor. At first, the lack of easily downloadable journal articles made me anxious: where would I find sources to footnote? But as I relaxed into this new mode of experiential mindfulness, I found myself gradually more willing to trust my own intuition, letting cross-cultural connections and synthetic thinking occur organically. I revisited the work of other great observational writers: Jane Jacobs, Ada Louise Huxtable, J.B. Jackson, Reyner Banham, and Umberto Eco, to name but a few favorites. I re-read William Zinsser’s classic non-fiction manual, On Writing Well. I followed along with the New York Times’ 52 Places Traveler, whose harried pace made me feel better about my own frantic itinerary. And most importantly, I pushed through my introversion and cultural shyness and talked with docents, guides, locals, and fellow tourists.

Experiential learning in progress at Cullinan Mine, South Africa and the Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture, Japan.

As I explored and read with an open mind, I found myself striving more towards the syncretic thought-webs of Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas or Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project rather than the microhistories I’d become so used to reading and writing. I was no longer aiming for that tiny, brilliant pinprick of new knowledge, but for networks of new connections within the existing sphere. The days I spent exploring non-industrial sites or art museums ceased to be days that I regarded as “off-task” and instead represented yet more opportunities for unexpected connections. My observations became Instagram posts, which in turn constituted the seeds of the monthly SAH blogs. In the months and years to come, I look forward to further developing my observations from the fellowship year into longer articles or a book.

Above, the Norwegian Viking Ship Museum in Oslo and the interior and exterior of Bokmål Heddal stavkirke in Notodden, Norway. Below, traditional wooden shipbuilding in progress on Chiloé, Chile, and the interior and exterior of the Church on Chonchi, Chiloé. Both forms of wooden architecture rely heavily on the techniques of naval architecture and carpentry. These were sites that I visited on “off days” from industrial heritage, but which added significantly to my experience and understanding of architectural history in a broader way.

Since returning to the United States, I have begun another research fellowship. I’m back in the archives and my shelves are again full of books. But I’ve brought the “Brooks style” of thinking and writing with me. The historic homes I’m currently studying are an hour’s drive from my office, and I’ve taken every opportunity to visit them along with a variety of guides and colleagues. I don’t go with any particular mission in mind, except to learn from the experiences of the people who know these places intimately.

Final Note of Thanks to SAH

I am immeasurably thankful to the Society of Architectural Historians for this truly life-altering opportunity. My parents provided substantial moral and financial support over the course of the year, and made the last few weeks of travel particularly meaningful and productive. My in-laws not only provided dog-sitting during the first half of my travel year, but opened their apartment in Paris to me while I explored Europe. The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum was flexible and understanding about delaying some planned projects a full year while I was away on the Brooks Fellowship. A whole array of friends and colleagues intersected with me over the course of the year, bringing new insights and welcome company to my adventures. Countless local guides, docents, AirBnB hosts, hotel concierges, and airline employees made me feel at home across the globe. Finally, I’m tremendously grateful to my husband, John Golden, who was my driver and companion across South Africa, Japan, and Chile, and my dauntless editor for nearly every written piece that I put out into the world.

With John Golden at the Tomioka Silk Mill in Japan.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top