-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Strangers in England

Aymar Mariño-Maza is the 2018 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

Figure 1: Dutch Gables in London

As Dutch As the Dutch Gable

The first thing you should know about the Dutch gable is that it’s not exactly Dutch. A more appropriate name for it might be the Low Country Gable, because it first appeared in the Middle Ages across what were then Dutch, Flemish, and Walloon regions. Sadly, that name isn’t nearly as catchy. The second thing you should know is that the Dutch Gable is to the English Renaissance what apple pie is to the USA. In other words, it is so quintessential that one easily forgets that it isn’t originally English. It was imported. And here we get to the question that is at the core of this text: who imported it? The answer, you will quickly realize, is not as simple as…well, apple pie.

With that, we’ve entered the grey area, the murky, questionable, and generally problematic area in which we’ll remain until the end of this text. That’s not just because we’ve arrived in the land of the ever-cloudy skies. No, the grey we’re entering is one brought on by a series of contending factors overlaid on very little documentation. (It just so happens that refugees have a tendency to find themselves smack in the middle of grey areas.)

Figure 2: Kew Palace, London

The Kew Palace is a manor house built in 1631 for Samuel Fortrey, economist, writer, silk merchant, and—of import to us here—descendant of a Protestant refugee. Aptly called the Dutch House, the Kew Palace is an example of Artisan Mannerism, a style of architecture prevalent in England in the 17th century. Artisan Mannerism, a bastardization of Northern Mannerism, itself a derivation of Italian Mannerism, often made use of the Dutch gable as an ornamental feature. Ironically, though the gable Fortrey chose is considered of Dutch origin, neither the gable nor he himself were Dutch. Fortrey was the grandson of a refugee from Lille, which is now France, but was at that point part of Habsburg-controlled Flanders. Add to this that the Dutch gable isn’t even entirely Dutch but more broadly of the Low Countries, that the way he utilized it was as an ornament and not as a functional gable, and that it was hybridized with the Renaissance pediment, and you begin to get a glimpse of the stylistic mess we’re about to dip into.

Figure 3: Strangers Gate as the side entrance to St. Mary's the Less Church, Norwich

Kew Palace is a revealing example of the murky history (and architecture) surrounding the influx of Protestant refugees that traveled across the channel into England from France, Wallonia, and Flanders. Commonly classified as Huguenots, these groups came to England as refugees from various religiously motivated unrests in mainland Europe.

Interestingly, the origin of the word refugee in English might surprise some readers. It is a mild butchering of the French word “réfugié.” Though the word has Latin roots, it was first introduced into the British lexicon in the 17th century, just as another wave of French Protestant refugees were “introduced” into the British refuge following the 1684 revocation of the Edict of Nantes.1 This is probably the most famous influx of these early refugees, along with the one following the St. Bartholomew Day Massacre of 1572.

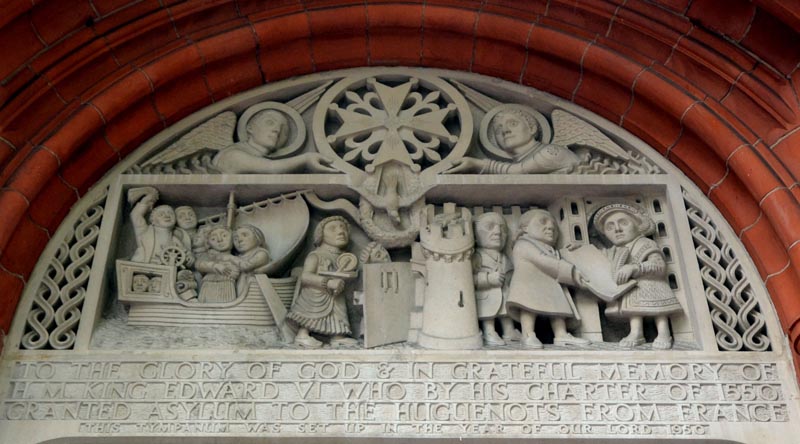

However, as early as 1550, twenty-two years before those assassinations of Huguenots in Paris, Edward VI had already signed a charter granting asylum to any Protestant refugees. This is because the French Huguenots were not the only group of Protestant refugees to enter England. By the mid-1500s, groups of Walloons and Flemish people were already making their way across the channel, driven by the Dutch Revolt, the religious and political civil war that waged between the Southern Hapsburg and Northern rebel-controlled regions between 1568 and 1648.

Figure 4: Artillery Passage in Spitalfields, London

Take A Step

A good rule of thumb for all those entering the grey area is to take a step back and another step out. Sometimes even the worst tangles at some point split into individual threads. The mess in the middle may never come apart cleanly, but at least the broader context can be untangled.

The Protestant refugees had an impact on the architecture of England, but that impact is tangled in a much larger mess of factors that influenced both England and its architecture at the time. In order to understand the impact that these refugees had on the architecture of England, a few of those contextual factors need to be explained independently.

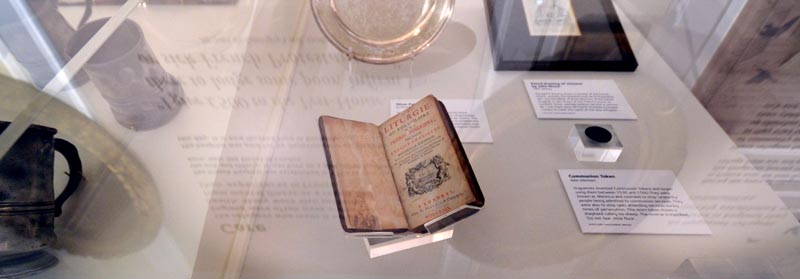

Figure 5: French Protestant Bible at the Huguenot Museum in Kent

The first is the advent of the printing press and the translation of the Bible into lay languages. Historian Samuel Smiles begins his text on the settlements of refugee Huguenots by speaking about the printing press—an apt tactic. To anyone who undermines the significance of using multiple sources, let the experience of the Protestant Reformation serve as a powerful precedent. Up until then, the only people able to interpret the holy text were those who could read Latin: in other words, priests. And, in other words, they were the ones who, under the auspices of the Roman Catholic Church, established society’s laws of religious conduct—as well as the respective punishments (and taxes) that were applied when these were broken. When Christians were finally able to read the Bible for themselves, they were no longer dependent on the parish priest to interpret the text for them. At that point, the Bible, the supposed “original” text, was used much like a secondary source: the reference with which to analyze the validity of the primary source that was the Catholic Church. And when, with their specific interpretive abilities in hand, these people found inconsistencies between sermon and text, they protested. Much in the way that the Hebrew Bible helped to perpetuate a cycle of displacement in Jerusalem, the translation of the Christian Bible was the catalyst that brought on the displacement of large groups of Protestant Christians from across Europe after the 16th century Reformation.

The advent of the printing press brought about the second factor we’ll mention: architecture books. Artisans and craftsmen across Europe (at that point, the architect was a relatively novel idea) were able to replicate the architecture styles that had been developed in Italy as well as the hybridization of these Renaissance styles with the vernacular architectures that already existed in other countries. The northern spread of Renaissance ideals and styles created these new hybridized architectures across northern Europe, styles which were then brought across the English Channel. This is a significant factor that explains the prominence of first Italian and then French and Flemish elements in Elizabethan and Jacobean architecture. As John Murray notes, “from 1550 on, British architects tended to copy the Dutch. The trend was undoubtedly accentuated by the great number of books on architecture published in the Low Countries.”2

This early form of information sharing isn’t entirely new, obviously, as trade networks, wars, and displacements have always brought about some form of cross-pollination. But the book sped up the process dramatically. The once distinct and iconoclastic styles secluded within the disparate parts of Europe began slowly to interact with one another, not as localized mixtures but as more general dissemination. This is a faint foreshadow of the deeply interwoven web of styles that make up the world we currently live in, due of course in part to that other great information-sharing revolution: the advent of the internet.

The third factor: the economic prosperity of Tudor England. Due to a series of interrelated factors such as shifting trade relations, the colonization of the Americas, the end of the Black Plague, and an upsweep in population,3 England’s economy under the Tudor reign grew. The expansion of the economy created a larger job market and urban growth in cities such as London, which went hand in hand with the integration of the new workforce, ultimately sweeping England into the industrial revolution.

Figure 6: Frontispiece over front door of French Protestant Church in Soho, London

The fourth factor has to do with the struggles between systems of power: the Protestantization of England. It seems that, if you pull hard enough, you find that all the troubles experienced by the masses can be traced up to those lucky few pulling strings. Power struggles between monarchs and their subjects, between monarchs and the Church, and between monarchs and other monarchs—that just about sums up the whole of European history up until World War I. One among this long list of struggles is of particular interest to us here: the gloriously blatant one between Henry VIII and the Catholic Church. This battle over marriage laws led to the creation of the Church of England. After breaking with the Catholic Church, the nation became a beacon for Protestants across the mainland. And, after its renewed Protestantism under Elizabethan rule, which began in 1558 (after the short return to Catholicism under Mary Tudor), England became a natural destination for the mainland Protestants fleeing persecution from the power of the Catholic Church. Elizabeth and subsequent monarchs’ dedication to the notion of religious freedom (superficial and tenuous though it may have been) was integral to defining England as a safe haven for those religiously persecuted by the Catholic Church across Europe at the time.

This transition in the country had an architectural expression, which leads us to the sixth and final factor we will note: the dissolution of monasteries across England. When the Catholic Church lost power in the country, all the monasteries, priories, convents, and friars were disbanded, then either recycled or destroyed. The newfound availability of buildable lands, coupled with the aforementioned burst of economic prosperity in the country, led to a great push to build new architecture. The powerful men of England therefore built luxurious manors upon these newly redistributed lands.

Figure 7: Flemish and French Mannerist details on the Jacobean manor house façade at Audley End House

Strange Influence

The Elizabethan and Jacobean styles were the architectural birth that came about when many of the previously described factors came together. An example that helps to illustrate this “factoral medley” is Audley End House, which itself is a historical medley. Originally constructed as a Benedictine priory in 1139 (then elevated to an abbey), the land and structure were acquired in 1539 by Sir Thomas Audley after the dissolution of the monasteries. Audley converted the abbey into a manor house and made a first set of alterations. In the first decades of the 17th century, Audley’s descendant, Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk, made more alterations to the mansion, creating the symmetrical double-courtyard configuration in the Jacobean style, of which only a single face of the inner courtyard survives.

Figure 8: Audley End House

A few craftsmen are credited with the Jacobean design, including the descendant of a Flemish refugee, Bernard Jenssen. Jenssen was a stone mason who may or may not have also taken part in the design of Northumberland House in the Strand (built by Howard’s uncle, Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton, on the site previously occupied by a convent). The obscurity of his involvement in both of these important designs may be due in part to the lack of documentation with regards to building craftsmen, stone masons, and carpenters at the time. And yet, the mere fact that his name, that of a first generation immigrant, is mentioned within the history of such significant buildings is if nothing else indicative of the manner in which some of the refugees managed to integrate into English society. If Jenssen did in fact contribute to the design, it might help to explain the pervasive—if restrained—use of Northern Mannerist details throughout the design.

When it comes to stranger influence on English architecture, the truth is that there are very few clean-cut answers. As we’ve noted before, there are many additional factors that help explain the French and Flemish architectural influences across England at the time that the refugees came. Among these are included the availability of books on architecture, the travels of craftsmen and builders, as well as existing trade between England and mainland Europe.

For these and other reasons, however, the fact is that the Low Countries had a significant impact on England at the time. As Murray states, “[t]he Low Countries were the bridge over which many European concepts and customs of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries crossed into England.”4

Figure 9: Blickling Estate, Norwich

It should be noted that the first known group of craftsmen that migrated to England from the Low Countries were not Protestant refugees. As the tourism website for Norfolk proudly reminds its readers, “the North Sea has always been a carrier, not a barrier.”5 Andrew Pettegree argues that the Protestant refugees coming into London “were able to join a well-established and settled foreign community in the city.”6 This community made up of merchants and workmen had inevitably begun to lay a mark on the city, not only within its architecture, but on also on culture, language, and the arts.

The style they were contributing to, as the reader will note in the various photographs, was still heavily set in what was already becoming the late Gothic style throughout mainland Europe. According to Mark Girouard, many have judged this style as a reactionary backslide in architectural style, while others have invoked the term Mannerism to explain the anti-classical tone of Elizabethan architecture (which is not a backwards conservative response to classicism, but a forwards emancipation from its restrictions).7 Whatever the subliminal intentions behind the style, the fact remains that it is a display of an architectural melting pot.

Figure 10: almshouse, Canterbury

The architectural impact of the Low Countries on English architecture, whatever roots it may have, is clearly extensive. Not only was it a strong influence in the 16th and 17th centuries, but elements such as Flemish brickwork and the Dutch gable were utilized well into the 19th-century Victorian Era. Much in the way the strangers were ultimately integrated into society, their architectural elements were adopted into the English architectural repertoire. Nowadays, it is supposed that one in every six English persons has Huguenot ancestry. Traveling through the southeast of England, it seems that nearly the same portion of English homes have some Huguenot influence. There are just so many Dutch gables!

The influence, of course, isn’t a simple matter of gable end décor. Custom House at King’s Lynn, built in 1683, is a design heavily influenced by Flemish architecture in an entirely different way. King’s Lynn was, at the time, an important maritime port linking England with Flanders and the home to a significant group of merchants and refugees from the Low Country. The baroque design of the custom house is a near perfect replica of the baroque civic buildings seen across the Low Countries, revealing just how influenced English craftsmen were by the architecture of the Low Countries.

Figure 11: Custom House, King’s Lynn

Weaver Town

In September 1666, a fire spread quickly across the medieval streets of London, engulfing large parts of the city in flames like the stacks of wood that it was. The fire exposed the urbanistic and architectural pitfalls of the city, problems such as too-narrow streets, lack of connectivity across the river, poor construction techniques, and the fire hazard of wooden construction. But these material bits were not the only things exposed by the fire. It also exposed what was apparently a shaky social relationship between Londoners and Strangers. Because, hidden under the well-known story of the accidental fire started in a bakery is the conspiratorial one of foreign terrorism, brought on by the arson of a city in the Netherlands at the hands of the British. Along with the flames, xenophobia spread through the city, leading to lynchings, convictions, and other violence towards immigrants and refugees from France and the Netherlands.

This is not to say that the overwhelming sentiment across England toward the refugees was negative. That has been proven false by such historians as Scott Oldenburg, who defends a sense of mutual solidarity between the English and Strangers even during the Catholic reign of Queen Mary.8 Nothing here is black or white. As we’ve already mentioned, it’s usually grey.

Figure 12: Detail of the facades of the weavers' homes on Fournier Street in Spitalfields, London. Note the penthouse spaces for weaving, posterior to the original construction.

Many of the refugees who came were artisans. Due to the labor demand within the weaving industry, upon reaching England many of those who might otherwise have been employed in other trades quickly transitioned, employing the weaving techniques they had once used simply to supplement their primary trades.9

As Christine Riding notes, the quality of craftsmanship among Huguenot refugees was well established in England, to the point that it was stated “hardly anything vends without a Gallic name.”10 On a more consequential scale is the role attributed to them by Lien Bich Luu within the development of England, and more specifically London, as the “engine of manufacture.” Luu argues that the immigrants served as “the principal conduit via which many skills and industries travelled from the more advanced parts of Europe to England, offering a faster route to industrial development.”11

The strangers became synonymous with weavers, specifically when it came to the more elaborate silk-weaving techniques. Spitalfields, the neighborhood with the largest concentration of Huguenot refugees, was known as Weaver Town. Strangers flocked to the area due to the readily available properties being constructed there and, more significantly, to its location outside the city gates and, consequently, outside the guild regulations. Nowadays, we still retain the shells of the material culture of this weaver town. The material in this case is mostly brick, some wood, and bits of glass.

Figure 13: Facades of the weavers' homes on Fournier Street in Spitalfields, London

Some examples of Stranger homes still survive. The ones pictured in this text were originally built as shells upon land owned by a pair of English lawyers. These shells would be rented out to the strangers, who would then fill them in and occupy them. The dissimilar style of the penthouses reveals how they were built: as utilitarian modifications included by the strangers at a later date. Since weaving silk is a delicate craft that requires a good amount of light, the additions were furnished with large windows in order to create well-lit work spaces. The newcomers were also responsible for installing the piping in these dwellings, and a few of their ornately branded pipes can be spotted on the facades of these buildings. A few more examples of such structures are scattered within Spitalfields. Examples include 18 Folgate Street, the known residence of a Huguenot silk weaver, and 56-58 Artillery Lane, an old Huguenot shop front from 1756.

Figure 14: Spitalfields Market, London

The architectural influence of the Strangers on Spitalfields doesn’t end there. Spitalfield weavers were an integral part of London’s economy and as such, many Huguenots involved in the trade became wealthy and even influential. A mark of this influence can be found at the very social center of Spitalfields: the Spitalfields Market. In 1682, King Charles II granted John Balch, a Huguenot silk throwster, the right to hold a market in Spital Square. Since its inception, the market has served as the economic center point of the East End and as a magnet for many future generations of strangers. From Jewish to Irish to Bangladeshi, Spitalfields and its bustling market have been home to a melting pot of immigrants and their dreams of becoming part of the ever-alluring city of London.

Figure 15: Christ's Church in Spitalfields, London. This 18th-century Anglican Church was funded in part by Huguenot descendants.

Walking through Spitalfields nowadays, it is hard to imagine the pastoral landscape that once served as the visual backdrop for the early immigrants settling there. Originally a hospital (from which the area derives its name—“spital” as in hospital) surrounded by fields, the Spital of St. Mary’s was dismantled after the dissolution of the monasteries, just around the time that the fields around it began to be urbanized. Soon after the Great Fire of 1666, the area lost all signs of what had once given it its name. Today, visitors can look down through a glass floor at the scarce stone walls that make up the rediscovered remains of the hospital.

Just as mercilessly, it seems, the refugees seem to have disappeared into the fabric of English cities and villages, weaving their way, though not without effort, into so many layers of English culture. Looking for the clues of the refugee settlements nowadays is a bit like trying to untangle single inconsistencies within a woven silk sheet, finding those near-invisible bumps, or spotting those single off-pattern knots. Thankfully, there have been writers, researchers, and descendants of these refugees that have invested the time to search for such subtle signs of life. If it were not for them, writing this piece would have been like trying to make an exact science out of if’s and if not’s. Because even when you spot what appears to be a sure sign of refugee influence, something like a Dutch gable for example, it’s usually too good to be true—or at least too good to be entirely true. If nothing else, let this study serve as a kind reminder to the traveler who does not take the time to research the spaces he or she visits that things aren’t always as they seem.

Figure 16: Brick Lane Mosque in Spitalfields, London

The unassuming building that marks the intersection of Brick Lane and Fournier Street tells the story of a much more powerful intersection. The building was originally built by Huguenots in 1741 as a Protestant church, then converted into a synagogue (after a short and unsuccessful bout as an Evangelical Christian conversion center for Jewish immigrants), and is currently a mosque. Nestled discretely into the urban fabric, this structure is a material metaphor for the long-term Huguenot experience in England. Recycled and rebranded, it is also a metaphor for the histories of the city at large.

Figure 17: Street in Sandwich

Sandwiched in the Brickwork

Sandwich is a little-known town a half-hour car ride from the tourist-filled Canterbury. Contemporary visitors would have a hard time reconciling its current sleepy scene with the town’s long history of economic, political, and naval significance. But if they take a moment to look past its culinary call to fame (the Earl of Sandwich is credited with inventing the sandwich so as to gamble without stopping to eat), they will be surprised to discover that the town was once one of the most important port towns of England.

Located strategically at the mouth of the Wantsum Channel, a major shipping route linking England and Continental Europe, Sandwich served as a maritime gateway into London, until silting in the channel made navigation of large commercial boats impossible. Declining the petition of the town to desilt the river, Queen Elizabeth offered instead an unexpected solution to the declining economy: refugees.

So, a hundred years after the last French forces destroyed roughly half of Sandwich, a different wave of people found their way into the town. The immigrants were granted permission to occupy many of the structures left in disuse or disrepair, with the requirement that these be repaired by the new owners. Material traces of these reconstructions can be found throughout Sandwich, where the Flemish applied their native brickwork and styles atop the original constructions. These constructions were already a medley of eras and regions, including stones taken from Roman walls as well as stones originally intended for the construction of the Canterbury Cathedral (but which were somehow left behind during the unloading and loading at the port). The Flemish bricks reveal but one layer within the beautifully messy construction of the town’s history.

Figure 18: St. Peter's Church, Sandwich

As early as February 1570, the local government passed a series of laws restricting the professional capabilities of its Stranger population. One of these measures being that “no carpenter, bricklayer or mason might work other than as a hired hand without official permission, unless an Englishman has already refused the job.”12

One example of this law being executed is the Fisher Gate, upon which the Strangers designed the third floor with its gable roof. Unable to construct it themselves, they paid for English citizens to lay the bricks. Another example is the Church of St. Peter’s. The Strangers were given access to St. Peter’s Church, once again with the caveat that they rebuild the structure but that the bricklaying be done by Englishmen. The tower, notably distinct from the rest of the façade, is the work of these Strangers.

But there is another element of interest in that façade, what John Hennessy, chairman of the Sandwich Local History Society, called a small show of rebelliousness on the part of these Strangers. Aggregated onto the main building and built much like so many walls across Sandwich—let’s go ahead and call it what it looks like: a “junkyard style”—we find the quirkily and playfully off-color Dutch gable.

Figure 19: Renovated building with exposed brickwork in the Flemish fashion

This “rebellious” Dutch gable, added by these refugees, is but one of the many expressions of rebelliousness that are literally and metaphorically rooted in the foundations of the town. Because, underneath the quaint image of medieval waddle-and-daub houses along the port street, lay the remains of smuggler dens, with their hidden storage spaces and underground tunnels that clandestinely connect the churches and the many pubs (so many pubs). Many of the Strangers that came to the town fit right in with this subversive culture, involved as they were in the Troubles of 1566 in Flanders. The Council of Troubles was the Duke of Alba’s response to heresy and rebellion, words which at that point were synonymous across much of Europe. Many of the new inhabitants of Sandwich were involved in the events surrounding the Troubles, returning at various point to Flanders and conducting secret meetings, prison breaks, and other forms of armed resistance.13 These refugees weren’t desperate and weak; they were rebels. Not exactly the image of Protestants with which we’ve grown familiar.

In fact, even in France, Huguenots were not a weak minority, and especially were not weak in terms of the contemporary French power dynamics. The state of things at the time of the Bartholomew Day Massacre looked more like the brink of civil war than a one-sided persecution. Of course, this state of civil war teetered on persecution at various times throughout the struggle, both within France and in the Low Lands. However, the fact remains that many of the refugees that made it across to England were not destitute or uneducated. As such, many were able to make a living, integrate into society, and positively affect their environments even as refugees.

So when refugees from Sandwich decided to move on to London, the impact was significant. Backhouse goes as far as to write that the Strangers’ emigration from Sandwich was akin to “signing the death warrant for the once prosperous town and port.”14 The decline of the town in terms of maritime importance was linked to a broader series of factors, among which the loss of those Strangers played a role, but perhaps not the dramatic one depicted by Backhouse. In the short time they populated the town, however, they left their mark, and not just that of a few bricks.

Figure 20: Interior of United Reformed Church, Sandwich

Hand-To-Mouth

When you imagine a Protestant, what comes to mind? It may be bold of me to say this, but I bet an image of self-restrained religious fanatics popped into your head like all well-formed stereotypes tend to do. Well, that’s exactly where we will turn to next. Because, like all stereotypes, this one has a grain of truth, and we can find that grain in architecture.

When the Strangers came to Sandwich, they helped build a church. Like good Protestants, they built a structure that embodied the values they wished to embody themselves. Adapting an outbuilding and recycling pieces of the boat that had brought them over to England, they helped fashion a space as austere as a Protestant Church ought to be. The unadorned space reveals the ideological intentions of its inhabitants, known as Independents, whose denomination was in large part a reaction to the extravagance and theatricality of the Roman Catholic Church.

Figure 21: Placard upon a column at the United Reformed Church, Sandwich, reading: “These two pillars were gifts of French refugees recognizing kind hospitality received in Sandwich. They are masts of the ships in which they reached these shores. Date 1685”

But this form of bare-bones expression of faith isn’t the only aspect of Protestantism that came to the fore of the refugee identity. Another aspect that marked the refugees was their charitable role in English society. According to law, the refugees were granted asylum so long as they took care of their own poor. As a result, giving alms became an integral part of the Huguenot way of life in England—as well as an important marker of their culture in the eyes of their fellow English neighbors.

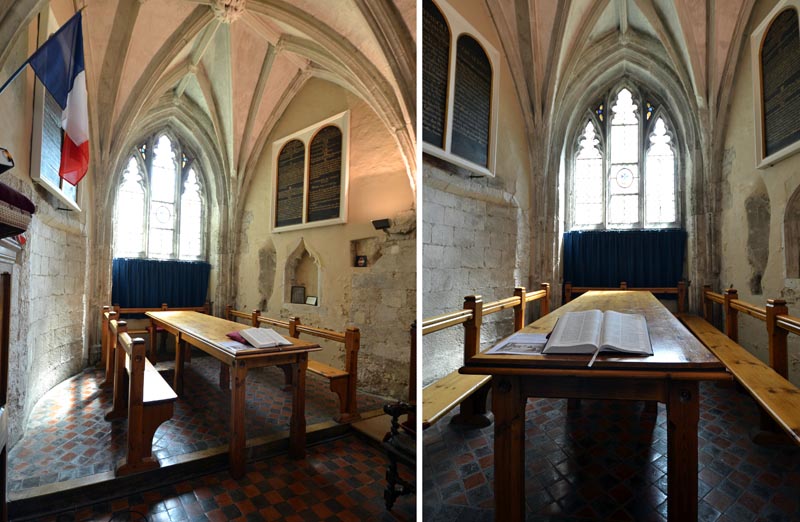

Figure 22: French Church in the Crypt of Canterbury Cathedral

Cryptic Ends

We’ll end with a disappearing act.

The Western Crypt at Canterbury Cathedral is the official home of the Église Protestante Française de Canterbury, granted to the Huguenot refugees in Canterbury by the royal decree of Elizabeth I in 1576. Easily filling the massive underground space, these early refugees numbered 2,500 by the end of the 16th century. The numbers fluctuated due to the influx of further refugees and natural causes such as the plague. However, the factor that had the most enduring trend is the assimilation of the refugees into the host community. Intermarriage and the Anglicization of these refugees led to the dwindling of the congregation. This dwindling is apparent in the shrinking of space allocated to the French Protestant Church within the crypt. As the numbers dwindled, so did the square footage of the church. It once filled out the entire western end of the crypt, but by the 1820s it was restricted to the south aisle. Nowadays, the church is contained in the Chantry of the Black Prince, which has been blocked off by elaborate wooden partition walls and fitted with the original wooden furnishings.

This spatial evolution is a material expression of how the Huguenots embedded themselves into English society, joining the Anglican Church and marrying into English families, all the while still sustaining a culture fiercely proud of its roots. It is heartwarming to see and listen to the descendants of these refugees looking fondly into their shared past. In a time where the refugee is so often denigrated and where so many struggle day in and day out with the stigmatization that comes with being thought of as “the other,” whether that’s because of skin color, religious expression, cultural norms, or the language one speaks, the expression of refugee pride exhibited like a heart upon the sleeve of these Huguenot descendants are an unexpected display of human dignity.

A few images of that pride stand out with tender clarity: an eager woman with grey hairs pointing up to a street sign and telling a smiling crowd that her ancestor lived right here; a tour guide with a stack of old photographs announcing, with a knowing glint in his eye, that his wife is a descendant of the Lefebvre family line; a spotlessly attired gentleman declaring, as he adjusts his suspenders, that he is able to give sermons in French and converse in Flemish; and the receptionist at the Huguenot Museum eagerly asking visitors if they have any Huguenot background—a question to which I unwittingly answered, “I’ve read a few books.”

Figure 23: French Protestant Church of Canterbury, interior of the Chantry of the Black Prince in the Crypt of Canterbury Cathedral

1 The Origin of ‘Refugee’. (n.d.) In Merriam-Webster’s Words At Play Dictionary. Retrieved from https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/origin-and-meaning-of-refugee

2 Murray, J. (1957). “The Cultural Impact of the Flemish Low Countries on Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century England.” The American Historical Review, 62(4), 837-854. doi:10.2307/1845516

3 Blanchard, I. (1970). “Population Change, Enclosure, and the Early Tudor Economy.” The Economic History Review, 23(3), 427-445. doi:10.2307/2594614

6 Pettegree, A. (1986). Foreign Protestant Communities in Sixteenth-century London. Oxford: Clarendon.

7 Girouard, M. (1963). “Elizabethan Architecture and the Gothic Tradition.” Architectural History, 6, 23-39. doi:10.2307/1568281

8 Oldenburg, S. (2009). “Toward a Multicultural Mid-Tudor England: The Queen's Royal Entry Circa 1553, ‘The Interlude of Wealth and Health,’ and the Question of Strangers in the Reign of Mary I.” ELH, 76(1), 99-129. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/27654654

9 Backhouse, M. (2017). “The strangers at work in Sandwich: Native envy of an industrious minority (1561–1603).” In Hermans T. & Salverda R. (Eds.), From Revolt to Riches: Culture and History of the Low Countries, 1500–1700 (pp. 61-68). London: UCL Press. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1n2tvhw.12

10 Riding, C. (2001). “Foreign artists and craftsmen and the introduction of the Rococo style in England.” In Littleton, C., Vigne, R. (Eds.), From Strangers to Citizens (pp. 133-143). London: The Huguenot Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

12 Kent Archives Office, Sa/Ac5, fos 166v, 179. See British Library, Manuscript Room, Additional 27, 462, fo.1

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top