-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

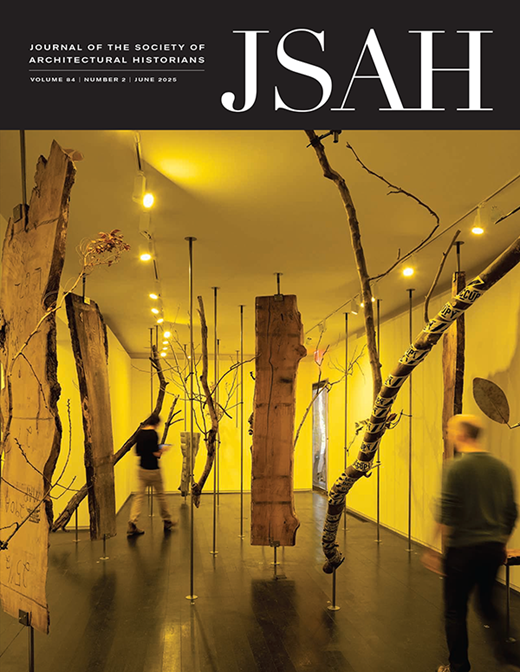

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Innovation and Institutional Memory at Dunbar High School

In December 2010 Adrian Fenty, then mayor of Washington, D.C., announced the highly anticipated plans for the re-design of Paul Laurence Dunbar High School. The Office of Public Education Facilities Management (OPEFM), a city agency created in 2007 to fulfill campaign promises for a complete overhaul of the school system, had conducted two design competitions in two years with the hopes of selecting a winning design for the Dunbar building. During the course of the two competitions firms the caliber of Foster + Partners, Adjaye Associates, and Pei Cobb Freed & Partners submitted designs for the twenty-first century manifestation of the high school.

In December 2010 Adrian Fenty, then mayor of Washington, D.C., announced the highly anticipated plans for the re-design of Paul Laurence Dunbar High School. The Office of Public Education Facilities Management (OPEFM), a city agency created in 2007 to fulfill campaign promises for a complete overhaul of the school system, had conducted two design competitions in two years with the hopes of selecting a winning design for the Dunbar building. During the course of the two competitions firms the caliber of Foster + Partners, Adjaye Associates, and Pei Cobb Freed & Partners submitted designs for the twenty-first century manifestation of the high school.

How did this design competition for a public high school become such a high profile event? Was it Washington politics as usual, showboating on the part of the mayor and city government, which had grappled with bad press on the state of the education system in the nation’s capital? What was at stake here?

Paul Laurence Dunbar High School, the first municipally funded public high school in the nation for blacks, was founded in 1870 as the Preparatory High School for Colored Youth. [1] The school moved numerous times during the next twenty-one years, housed in makeshift locations until finally settling at M Street between First Street and New Jersey Avenue, N.W., where the first substantial building for the school was constructed. It was rededicated as the M Street School and remained there for twenty-five years.

In 1916 a new building was erected in response to the growing student body – the design of the school building by municipal architect Snowden Ashford was a testament to the hopes and wishes of its community. Ashford was credited with more experience building and maintaining schools than any other architect of the early twentieth century. [2] One critic later noted that because Ashford did not discriminate in design “Washington's black schools were separate but truly equal to their white counterparts.” [3] The three-story building employed Tudor references with a running parapet along the roof and a central fortified tower on the facade, and contained large windows and a ventilation system. On January 17, 1916 the new M Street High School was renamed Paul Laurence Dunbar High School in honor of the deceased poet.

Throughout segregation, and despite overcrowding over the years, Dunbar High School flourished, upholding the high tradition of its predecessor the M Street School. Dunbar’s academic success was born out of racial discrimination during the era of segregation – its concentration of highly educated black teachers, some of whom held doctorates, were denied employment at other educational institutions. This misfortune turned out to be a blessing for students who were guaranteed a first-rate education at Dunbar.

As a result of the commanding faculty, combined with a rigorous college preparatory curriculum, Dunbar sent many of its graduates to a number of prominent colleges, including Howard, Amherst, Williams, Oberlin, Radcliffe, Smith, Harvard, Vassar, and Yale. [4] Some of the better-known graduates of Dunbar include Benjamin O. Davis, the first black general in the United States Army, and innovator in blood plasma research Dr. Charles Drew. Suffragist Mary Church Terrell and educator Anna Julia Cooper, one of the first black women to receive a Ph.D., both taught at the school. Cooper also served as principal of the M Street High School for the school from 1902 to 1906.

Desegregation and a population shift stemming from the Second Great Migration played a major role in the perceived decline of Dunbar as a leading educational institution. While the process of desegregation did not change the racial demographic of Dunbar’s students, due in part to a Board of Education clause that stated students were prohibited from attending schools outside their neighborhood residential boundaries, it did dramatically change the socioeconomic status of the students. The academic change within Dunbar High School was more drastic than its physical transformation as the school’s prestige began to diminish. The school slipped from high rankings and association with Washington’s African American upper-middle-class in the 1950s to ultimately being characterized as "a failing ghetto school" by conservative economist Thomas Sowell in 2002. [5]

After the 1968 riots that followed the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the District of Columbia Redevelopment Land Agency collaborated with the Model Inner City Community Organization (led by Walter Fauntroy) in an effort to revitalize the school’s neighborhood while combatting the increasingly negative reputation of the school and its facilities. The new $17 million Dunbar High School constructed in 1977 by Bryant & Bryant was both a high-rise and open-plan school. The success of open-plan schools was particularly dependent on the correct implementation of their design with new teaching methods that worked to complement the specially configured spaces, innovative furnishings, and carpeting. Teaching methods included team teaching, modular teaching, and non-graded levels of instruction that emphasized the individuality of each student’s learning processes.

Washington Post architecture critic Wolf Von Eckardt praised the new design noting “its brick and mortar arrangement does away with the confining, authoritarian rigidity of the old egg crate classrooms and recognizes that the constant in our time is change, that education is a fluid process.” [6] The design was the most ambitious, avant-garde, and expensive for a public school in the metropolitan area, costing more than four times the amount estimated to bring the 1916 building it replaced up to code. [7] The ahistorical approach to the new design signified a rejection of the past and a focus on contemporary and future needs, revealing the strong disconnect between past accomplishments and the state of the institution in the 1970s.

The competition-winning design announced by Mayor Fenty in December is by the team Ehrenkrantz, Eckstut & Kuhn and Moody-Nolan. In many ways, it resembles the 1977 building it replaces: it is at the forefront of contemporary design practices for educational facilities, it incorporates flexible learning spaces, and it intends to re-define monumentality in a modern context.

The new school differs in its embrace of the past and historical figures associated with the institution. Yet in the 120 years since the erection of the M Street School facilities, the institution has been housed in three different buildings, and by 2014 the number will be increased to four. The constant reincarnation of Dunbar every thirty years strikes at the heart of the institutional memory of the school, creating a fractured narrative of the nation’s first high school for blacks. Additionally, the tradition of politicians and activists using Washington public schools as experimentation grounds for policy and architecture leads to a repetitive cycle of high design, incompetent maintenance, and destruction.

Dunbar is a particularly worthwhile case study because of the historical association of great accomplishment that continuously pushes its innovative designs. Here, the grand posturing of the school’s architecture reveals an insecurity about the academic and cultural climate of the institution today, and the belief that architecture does have the power to redirect the course of a school that has depleted and fractured institutional memory.

Notes

1 U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form for M Street High School , 2.

2 See Kimberly Prothro Williams, “Schools for All: A History of DC Public School Buildings 1804 – 1960,” District of Columbia Historic Preservation Office (2008).

3 S. J. Ackerman, “Architect of the Everyday,” Washington Post , November 6, 2005.

4 Jervis Anderson, “A Very Special Monument,” New Yorker (March 20, 1978): 93, 100.

5 Thomas Sowell, “The Education of Minority Children,” in Education in the Twenty-First Century , ed. Edward P. Lazear (Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 2002), 79-92.

6 Von Eckardt as quoted in Jervis Anderson, “A Very Special Monument,” New Yorker (March 20, 1978): 111.

7 Michael Kiernan, “Razing Fight Begins Anew,” Washington Star , February 28, 1975, B 1.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top