-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

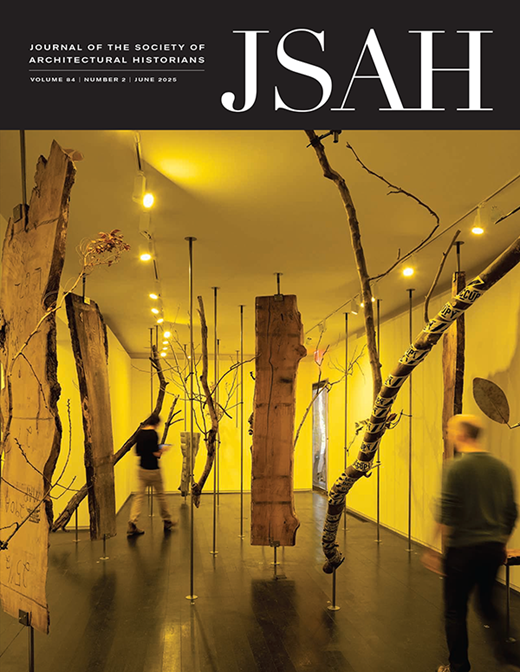

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Syria’s Cultural Heritage: Another Casualty of War

As I lectured on the Great Mosque of Damascus in my Introduction to Islamic Art class a week ago, I thought: my students may not have a chance to see this masterpiece. It too could fall victim to the devastating violence underway in Syria. And just two days ago, on April 24, 2013, the early medieval minaret of the Great Mosque of Aleppo was reportedly collapsed due to shelling. (Before-and-after photo above from BBC.)

For an architectural historian of the Middle East, the last couple of years have been both exhilarating and devastating. The Arab Spring continues to unfold, transforming societies and spaces in unpredictable ways. On the one hand, public spaces in cities like Cairo are more vibrant than ever. Tahrir Square has become a household term associated with revolution and youth movements. On the other hand, in Syria, the Arab Spring has devolved into a violent conflict with no end in sight. The human cost is shocking: over 70,000 Syrians dead, and counting.

Why is it that cultural heritage is an inevitable target in any civil strife, war, or atrocity? As the human cost mounts in the conflict in Syria, cultural heritage has become collateral damage. Some sites have become theatres of war: like the citadel of Aleppo, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world. Some sites, deserted for centuries, are occupied again by refugees fleeing the conflict: The famous dead cities in Northern Syria, unique witnesses to the history of early Christianity. Late antique ruins and catacombs hardly provide the amenities of everyday life to traumatized displaced people. but they are a place to hide for a while.

And looters, both professional and amateur, are taking advantage of the breakdown of law and order to conduct “informal excavations” in archaeological sites or taking objects from museums. They are harvesting artifacts to sell on the black market.The region includes well established neworks of artifact smugglers. Syria is experiencing a version of what happened in Iraq: museums looted, archaeological sites plundered, a thriving black market. It has been reported that groups are selling antiquities on the black market to buy weapons.

It is very hard to document the damage to Syria’s cultural heritage accurately and comprehensively. Syrians are extremely proud of and attached to the ancient history of their country; many of them, amateur guerilla reporters and activists, have compiled a mass of raw data, video and information about the destruction of cultural heritage. Emma Cunliffe compiled a sobering report in May 2012. ICOM is in the process to compile a “Red List”, a list of artworks that have or may be looted, as a guide to Interpol.

What will happen? I stubbornly cling to the hope that Syrians and Syria will get past this conflict, they will rebuild and repair lives and monuments and social bonds. I hope, but in fact, no one knows.

I dread the point in this Spring where we will discuss the Citadel of Aleppo, that astonishing masterpiece of medieval military architecture perched on a hill layered with monuments from the most ancient periods of human habitation. I want to show my students the raw footage of the destroyed gates of the citadel, with the now-smashed victory inscription of Al-Zahir Ghazi, one of Saladin’s sons. Our students need to know how fragile the built environment is in conflict and war. We cannot look away.

| HEGHNAR WATENPAUGH is a historian of art and architecture of the Middle East at the University of California Davis. She is interested in cultural heritage, gender, and space. |

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top