-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

The Right Textbook

It wouldn't be late August, if I weren't gripped by the annual anxiety that I have chosen the wrong textbook for the imminent architectural survey starting in a few days. The year-long survey (ancient to medieval in the Fall, Renaissance to late modern in the Spring) is a staple of our teaching whether in departments of art, architecture, or art history. This year's anxiety comes with the realization that I have taught a version of this survey continuously for a decade and in a range of public, private, small, and large universities. But I also realize that I have never used the same textbook two years in a row. Every April an inevitable sense of disappointment with the current textbook throws me into a crisis that translates into a different choice for next year's bookstore order. As the new academic year lurks around the corner from summer's pedagogical distance and scholarly satisfaction, the text book choice of April (the cruelest month) comes with a dose of self doubt. My seasonal anxiety was heightened this August after finding a new package in my departmental mailbox, a review copy of Richard Ingersoll's revised Spiro Kostof in World Architecture: A Cross-Cultural History (2013).

Teaching architectural history is a complex enterprise with competing narratives, methodological styles, and philosophies. Like our fellow art historians, we face a finite set of options (Gardner, Janson, Stokstad) established by publishing houses that contribute to our students' amassing of debt. Based on my own conflicted experiences, this is how I map out the textbook terrain for a general college-level introduction to architecture.

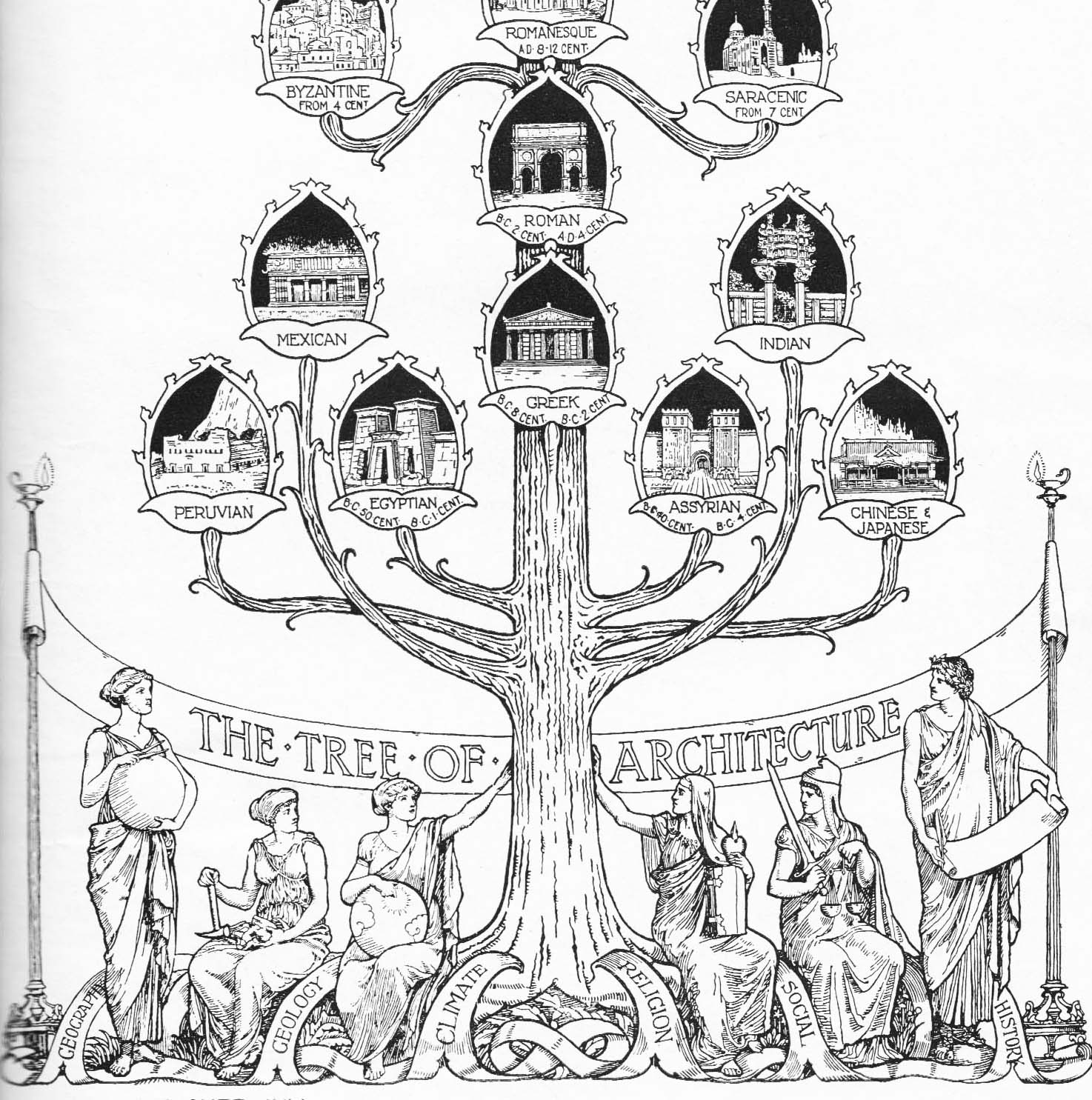

The High Road. One classic approach to architectural history is to keep it elevated within the realm of high art. Educated in a Warburg School academic genealogy, Marvin Trachtenberg's Architecture: From Prehistory to Postmodernism (1986) was my point of entry. As a specialist in premodern architecture, in particular, I marveled at Trachtenberg's ability to animate the canon with the spirit of the liberal arts and the ideals of high culture. Although serving well advanced art history majors, Trachtenberg proved to become more and more unworkable with a general student pool. David Watkin's History of Western Architecture (1986) is another alternative, but its brevity on ancient architecture always discouraged me from adopting it. Built on the tradition of Nikolaus Pevsner's Outline of European Architecture (1943), the high road proudly asserts that architecture is a cultural expression superior to ordinary building, after all, "a bicycle shed is a building; Lincoln Cathedral is a piece of architecture." Thanks to the migration of Germany's prominent architectural historian, the high road flourished in the late 20th century, replacing older American models, such as Banister Fletcher's comparative method or the associationist tendencies of Ruskinian aestheticism.

The Social Edge. For those trained in a more vernacular or anthropological approach, Spiro Kostof's A History of Architecture: Settings and Rituals (1985) has been an obvious choice. In spite of my scholarly anthropological affinities, I had always found Kostof more difficult to teach, as it failed to essentialize in ways that were expedient and necessary for the art-historical curriculum. Kostof seemed especially weak in Trachtenberg's periodic strengths and my own fields of interest in the Middle Ages. As Robert Ousterhout noted, Kostof's Byzantine chapter is one of the weakest, which is strange considering that he was a native Constantinopolitan. Ingersoll-Kostof's new World Architecture fills me with hope, although sadly the book came too late for this year's choices. Ingersoll has complemented Spirof's "democratic" approach with broad global strokes. Organized under 20 chronological periods that are defined by date alone, rather than by civilization, Ingersoll offers tackles three settings with its period. Although one fears that this might prove too complicated for a teleological schema, Ingersoll opens up the possibilities of selecting one's personal narrative from the 60 case-studies. So it is possible to tell the good old story of Romanesque begetting Gothic, the Renaissance begetting Baroque, etc.

World Architecture. It has become increasingly difficult to teach western architecture in isolation. Nevertheless, western architecture is a tradition that, if diluted too much, fails to have a disciplinary force. Seeking to satisfy a global breadth, Building Across Time: An Introduction to World Architecture (2008) maintained the canonical western sequence but added substantive sections on Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Michael Fazio, Marian Moffett, and Lawrence Wodehouse have made the shift from western to global as easy as it can be. I have enjoyed their approach very much, although the non-western chapters struggle to fit with the western story of prominence. Bridging the divide of cultural versus social expression, Fazio, Moffett, and Wodehouse seemed to have succeeded in producing a well illustrated textbook. I would have staid more loyal to the enterprise had the later chapters been as strong as the earlier ones. The last section on late modernism and beyond seems to have disintegrated into a list of options.

Building Language. What teachers of architectural history confront is an utter illiteracy among the students on how to read visual form in the built environment. Whether western, global, or sociological, the standard textbooks had assumed some kind of foundation in the virtual world. Since the survey of architectural history is commonly the only architecture class that students may take, building a linguistic basis for understanding the constructed world becomes an increasing need. This challenge had already been clear to historians teaching in schools of architecture, where the past offered the linguistic foundation for design. Francis Ching's Architecture: Space, Form, Order (1975), Steen Eiler Rasmussen's Experiencing Architecture (1959), and Christian Norberg-Schultz's Meaning in Western Architecture (1975) have all been wonderful primers to the phenomenology of architecture, but have not made good substitutes to the historian's discipline. Leland Roth's Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History, and Meaning (2007) is the best alternative for an integrative linguistic approach. Roughly a third of this compact book is devoted to the Vitruvian architectural basics (utilitas, firmitas, venustas) before tackling the albeit short chronological sequence. I know that a few other architectural historians invested in "understanding" buildings have abandoned textbooks altogether. Others use Carol Strickland's sparse Annotated Arch: A Crash Course in the History of Architecture (2001) that complements with original sources material and hands-on exercises.

Thematic Entanglements. When the Oxford History of Art series adopted a thematic approach to its textbooks, I was very excited. Dell Upton's Architecture in the United States (1998) truly rocked my world and gave me countless hours of productive discussions in seminars geared to the American scene. Similarly, Barry Bergdoll's European Architecture 1750-1890 (2000) remains my favorite primer to that complicated century-and-a-half of proto-modernity. Unfortunately, the thematic approach is inconsistent in both chronological coverage and quality. Even in times where I have succeeded in weaving a tapestry of thematic readings, the students have become frustrated with the different voices confronting them with every turn. I have found it impossible to string along enough thematic textbooks for an extensive survey. The verdict is not out, of course, but it seems that the students flounder in a thematic framework because most lack the rudimentary chronological foundation. I find that many students love architectural history because it gives them a primer in the sequential dialectic of cultural and social expression. Their architectural history might be their only college level history and they crave a coherent textbook.

Perhaps I'm restless. Perhaps I expect wonders from a textbook. Perhaps I put too much value to these choices. But I don't find myself alone in lacking confidence when asked, "What is your standard textbook?" Even after ten years of trying, I am still searching for a stable textbook to partner with for the next decade. I need a book whose exorbitant cost I can at least justify to the students in good faith. By testing different books each year, I make my job harder, needing new images, new dates (which range wildly from textbook to textbook), and new assignments. At the same time, switching textbooks keeps me focused on some pedagogical concerns. I would like to think that one day, we'll have enough digital resources to make this nagging choice go away. Most likely, the choices will multiply and in their cheapness become more burdening.

I thank my students over the years for test-driving all these expensive choices. I am sure that they are all well served considering the chaotic alternatives. If you have a favorite textbook in your survey, please, tell us about it. I look forward to a permanent relationship.

"The Tree of Architecture" above, comes from Banister Fletcher's old classic, A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method for Students, Craftsmen & Amateurs (1st ed. 1896; last ed. 1986)

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top