-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Berlin: Post-War Reconstruction (or Destruction)

Sundus Al-Bayati is the 2019 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

From Baghdad to Berlin

In my first week in Berlin, my Pacer app. registered 62 miles walked. Berlin had unusually sunny weather after weeks of rain, so I didn’t want to waste any days sitting inside recovering from my jetlag, and I thought this would be a good opportunity to get to know the city straightaway. I think Jane Jacobs would agree. On my map, I outlined the sites and buildings I planned to see that were either destroyed during World War II or rebuilt after the war. I wanted to get a sense of the city first. Walking allows your mind to wander. My mind drifted back in time to the early 20th century, when the German Empire sought to expand its colonial power by connecting Berlin to Baghdad through The Baghdad Railway.

The Baghdad Railway, also known as the Berlin-Baghdad Railway, built from 1903 to 1940, was a way for Germany to strengthen its alliance with the Ottoman Empire and assert its power as a rival to Britain and France in the Middle East. The Railway would allow Germany to establish a port in the Persian Gulf, granting it access to valuable oil reserves in Iraq, and linking Germany with its colonies in Africa.1 The Baghdad Railway was part of the Ottoman Empire’s plans to develop railways to link Turkey and Iraq. The increasingly weak and indebted empire granted the bid for the construction of the Baghdad Railway to Germany’s Deutsche Bank. When World War I broke out in 1914, the Baghdad Railway was 600 miles short of its planned destination. I often wondered what kind of Baghdad it would have been had this train route existed between the two cities. Maybe instead of applying for an entry visa to Germany a month in advance, detailing my arrival and departure dates, presenting my bank statements, providing proof of address and legal residency in the U.S. and submitting booked accommodation in Berlin (before I know if I am allowed to enter the country or not), I could hop on a train from Baghdad and find myself in Berlin two days later. Mobility is a theme I fantasize about frequently being an Arab and from a Muslim country. Everywhere I go, my passport is scrutinized, and I am subjected to a lengthy visa process. I never know whether I am going somewhere until I arrive there. This year of travel will be an adventure.

As I navigate the visa process for each destination, the COVID restrictions, and the political climate in my war-torn cities, my itinerary might change. Unfortunately, there are too many cities whose urban landscape has been completely changed by war and conflict that I couldn’t fit in my year-long exploration, which I might explore if my planned itinerary is disrupted. The cities on my list are not unique in their experience of war. War and destruction have always been the history of cities. However, war in these cities is positioned in a time that is not too far in the past and not too recent that enough can be observed about their different processes of reconstruction and its effects in shaping the urban landscape. This is the reason why Baghdad, where I grew up during the UN sanctions of the 1990s and 2003 war, is not on the list. Baghdad is still in a state of destruction.

I cannot think of a more intriguing city to begin this research into the complexity of post-war reconstruction than Berlin. Not only did half of the city get damaged during World War II, but the preceding era of Nazism, and the subsequent years of the city’s division manifested to the world as the Berlin Wall, make Berlin a city that continuously contends with its identity and past. This struggle is present all over the city.

In his War and Architecture pamphlet from 1993, Lebbeus Woods identifies two patterns of post-war reconstruction: either erasing the old site and creating a new utopia or restoring the site to its previous pre-war condition. Woods distinguishes between two approaches of reconstructing destroyed buildings according to their type: “ordinary buildings” such as apartment buildings and offices, as well as “symbolic structures” such mosques, churches and public buildings.2 While I don’t agree with Woods that a building type could solely drive the process and narrative of reconstruction, I think it is important to differentiate between the scale of a singular structure, such as the building block, and the scale of a group of structures like the neighborhood block. For this post, I’d like to focus on two iconic buildings in Berlin that offer two somewhat opposing examples of reconstruction.

Topography of Terror Museum

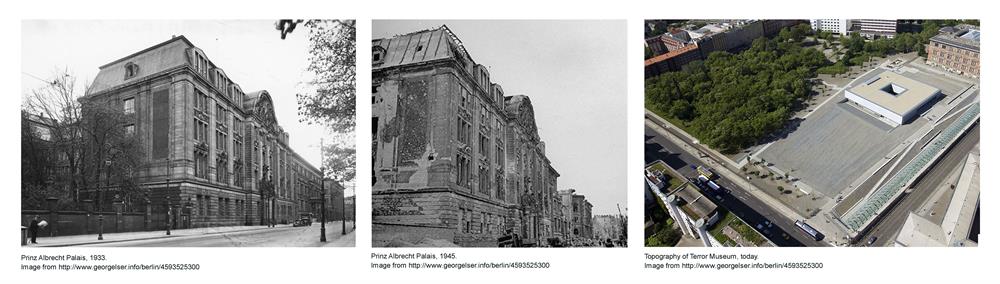

The first stop I made in Berlin was the Topography of Terror Museum. The site, formerly the Prinz Albrecht Palais, used to house the headquarters of Gestapo, Sicherheitspolizie, SD, Einsatzgruppen and SS Reich Security Main Office. The evolution of this site since World War II is a salient example of one of Berlin’s longest and most contentious debates about post-war reconstruction and its associations with the city’s history and identity.

Topography of Terror Site (click to view full-size image)

Prinz Albrecht Palaist was built in the 18th century, and later renovated by Berlin’s most prominent architect of the 19th century, Karl Friedrick Schinkel. The site was destroyed during the Allied bombing in 1945 and sat in ruins until 1949, when the West Berlin government blew up the rest. By the mid-1950s all the SS and Gestapo buildings were demolished and the rubble was cleared. The buildings weren’t so damaged as to warrant their demolition but nobody wanted to preserve the “most feared address in Germany.”3

The act of deliberately erasing what remained of one of Berlin’s historically critical landmarks and especially one without any public input would later determine the future of the site when a new generation perceived this action as a way for their government and its people to erase their tainted past and deny their connections to Nazi Germany.

Until 1981, the site sat vacant and was leased for different uses, such as to hold debris from nearby construction sites.4 In 1986, pressured by the “Active Museum of Fascism and Resistance in Berlin,” the city government led an excavation at the site and discovered the jail cells of the Gestapo.5 The discovery led to the establishment of the Topography of Terror exhibit the following year. The positive reception of the exhibit led to a rethinking of the site; following the German unification, a design competition was established to invite architects to design an exhibit space and a documentation center to continue to investigate the Nazi past. Peter Zumthor’s design was selected but the construction stopped few years later due to funding difficulties and debates about Zumthor’s design. The Zumthor design was dropped and a decade later a new architect was selected, the German architect Ursula Wilms.

As I approached the museum, I was surprised by how desolate the site felt. The new museum consists of an indoor exhibit and documentation center and an outdoor exhibit that occupies a small footprint. The rest of the site is left untouched. I learned that was the most important design criteria established by the museum commission. The sense of flatness and desertedness I felt is meant to document the deliberate flattening of the site and the subsequent years of neglect and disregard by the West Berlin government in its attempt to erase the Third Reich. The site remains a representation of the complicated relationship between Berlin and its difficult past.

The indoor exhibit, a rectangular box of metal and glass, almost hovers on the site to disrupt its history as little as possible. The outdoor portion of the museum brings the visitor close to the exposed jail cellars of the Gestapo where people were tortured and imprisoned.

Excavated Gestapo prison cells make up the outdoor exhibit

This example of post-war reconstruction challenges the traditional approach of rebuilding a replica of the old 18th-century palace that was destroyed and instead documents the historical and political forces that formed the site since the war. This form of reconstruction sees architecture beyond a mere object to be replicated to restore pre-war normalcy, but as a product of lived and shared experiences that constitute the complex narrative of a city. In its minimal intervention, the site retains evidence of the Third Reich and records the city’s dialogue with its uncomfortable past.

The Humboldt Forum

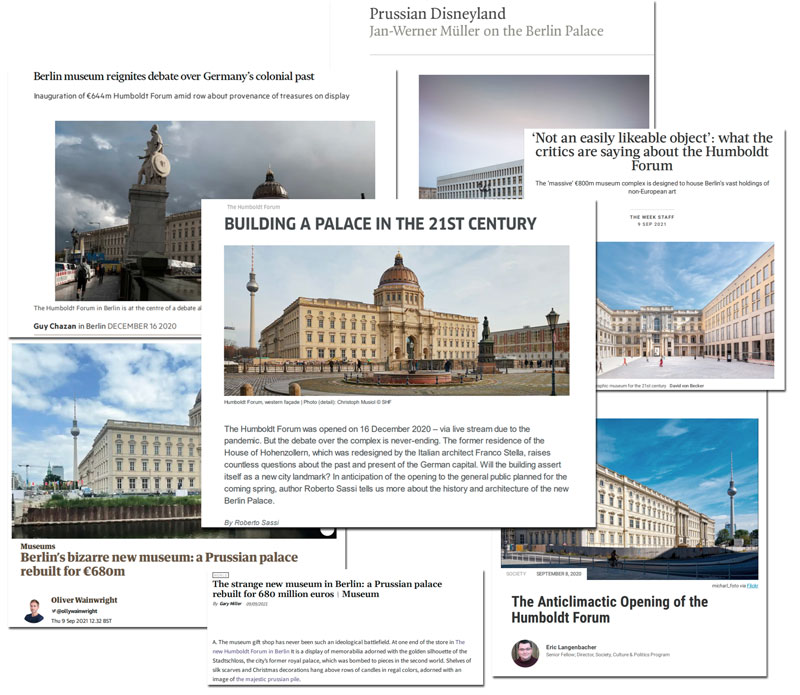

A thirty-minute walk east of the Topography of Terror Museum stands another controversial example of post-war reconstruction: the Humboldt Forum, or as the political science professor Jan-Werner Müller calls it, “Prussian Disneyland.” It’s a lucky coincidence for me to be in Berlin while the controversy about this building is very much present in the minds of Berliners. The museum opened its doors on July 20th. Perusing news articles around the time of the museum’s opening gives an idea about the ongoing controversy directed at the architectural form of the building that unapologetically reconstructs an icon of Germany’s colonial past. The debates about the reconstruction of the palace have been ongoing since the fall of the Berlin Wall.

A snapshot of recent articles following the opening of the Humboldt Forum

The newly opened Humboldt Forum, view from the Spree River, Berliner Dome on the right

Reconstructed baroque facades against the modern concrete grid of the eastern facade

Reconstructed baroque facades against the modern concrete grid of the eastern facade

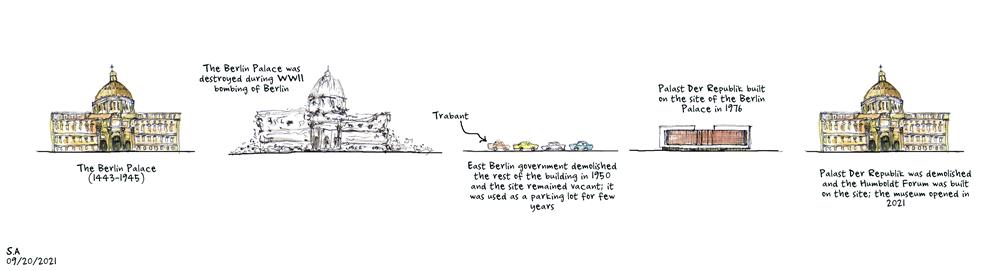

The original Berlin Palace was built in 1443 and became the royal residence of the Hohenzollern until 1918. King Fredrick I of Prussia ordered the expansion of the palace, which was completed by architect Andreas Schluter in 1713 to become one of the largest and most important buildings of Northern Baroque architecture.6 The palace was severely damaged during the bombing of Berlin, but other parts of the building, including the iconic facades, survived. After a few years of neglect, the East German government demolished the building in 1950, claiming the site too damaged to preserve. They proposed it become a square for mass demonstrations for the proletariat to express their struggles and needs. The site remained undeveloped for over a decade and was used as a car parking lot until 1973, when a new building was constructed by the GDR government, the Palace of the Republic.7 The new modernist building housed the Volkskammer, the parliament of the German Democratic Republic, as well as public and cultural spaces like a bowling alley, cinemas, theaters, and restaurants.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Palace of the Republic was closed due to the discovery of asbestos contamination. In the following decade, controversy about the future of the site took central stage again in Berlin between proponents of demolishing the site and reconstructing the vanished Berlin Palace as a symbol of unified Germany and preservationists and activists who saw the Palace of the Republic an integral part of the history of Berlin and its divided era.8 Nonetheless, in 2003 the Bundestag voted to demolish the building, and it was not until 2007 that a decision to rebuild the 18th-century Berlin Palace—or parts of it—was passed.9 The plan was to rebuild three of the lost facades and the Berlin Palace dome, based mainly on photographs since no detailed drawings of the building exist, and have the interior of the building serve as a space for cultural programming. Today, three of those new-old facades stand next to a fourth of a modern architectural style. It now houses a collection of non-European art such as artifacts from Asia and Africa, looted by the German Empire.

The newly reconstructed baroque facades of Humboldt Forum

Humboldt Forum and Berlin Television Tower (Berliner Fernsehturm) to the right

The Atles Museum viewed from inside the courtyard of Humboldt Forum

An interior courtyard in the Humboldt Forum where modern and baroque walls meet

Close up of the reconstructed baroque details in the interior courtyard of the museum

Before it was reborn as the Humboldt Forum, the Berlin Palace was sort of temporarily reconstructed once before. In 1993, the businessman Wilhelm von Boddien founded a lobby group that was essential in winning the debate to rebuild the Berlin Palace. Using private funding, the group managed to erect two full-scale facades from painted canvas attached to a massive scaffolding structure.10 The idea was to demonstrate the importance of this reconstruction in reclaiming its place back in the historical center of Berlin next to the Berliner Dome and the Berlin Cathedral. This was a successful strategy to win favorable public opinion. The art mockup is an uncommon example of public participation in the discussion of what replaces a destroyed building in the aftermath of war and its implications for people’s sense of history and place. Was the public manipulated by nationalists?

Sketch_Understanding the History of the Site (click to view full-size image)

Being the latest creation at the end of a long cycle of construction and destruction, the Humboldt Forum stands as a clear example of how a city’s buildings are continuously molded by ideological and political forces. More importantly, it demonstrates who has the power to decide what stands in the place of a destroyed building and thus deciding what fragment of the past is told. The recent controversy is focused on the use of the Humboldt Forum for the display of looted objects but there is another equally important debate: was the erasure of the Palace of the Republic that already stood there for over 30 years warranted? To intentionally deconstruct an existing landmark that represents the very identity of this city, the city of the Berlin Wall, and construct in its place an empty vessel of a vanished royal past, seems to be no more than an act of vengeance and a symbol of triumph of the neoliberalism that West Germany pivoted to immediately after World War II.

The two iconic sites, on opposite sides of the Berlin Wall, are two among many destroyed during the war but they are exemplary in their ability to present a fundamental theme in the narrative of this city, the ongoing struggle between remembering and forgetting.

History of the Site

The Palace of the Republic lives on in the museum store as keychains and cups among other things

Marx and Engels Statue remains in Marx-Engels Forum in front of the former Palast Der Republik and the current Humboldt Forum

References:

1 McMeekin, Sean. The Berlin-Baghdad Express the Ottoman Empire and Germany's Bid for World Power. Belknap, 2012.

3 Topographie Des Terrors, https://www.topographie.de/en.

4 Ladd. The Ghosts of Berlin: Confronting German History in the Urban Landscape. The University of Chicago Press, 1997.

6 Ledanff, Susanne. “The Palace of the Republic versus the Stadtschloss: The Dilemmas of Planning in the Heart of Berlin.” German Politics and Society, vol. 21, no. 4, 2003.

7 Ladd. The Ghosts of Berlin: Confronting German History in the Urban Landscape. The University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top