-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

John Jager: Unknown Prairie Architect in Minnesota. Part 1

John Jager (1884-1947) was an artist, intellectual and Prairie School architect whose work has gone almost completely unrecognized, due in part to a career split between Europe and the United States, and in part to his own insistence on anonymity. Jager was described by William Gray Purcell, his lifelong friend, as the “silent partner” in the firm of Purcell and Elmslie. Purcell and Elmslie rivaled Frank Lloyd Wright in the number of Prairie School commissions completed, but Jager fell into self-chosen obscurity following the dissolution of Purcell and Elmslie in 1921 and the crash of 1929. I was fortunate to encounter the work of Jager while working on a National Register of Historic Places Nomination for Wolf Island, MN. Jager never abandoned the ideals of progressive and organic architecture, and spent well over twenty years of his life crafting Wolf Island into his vision of a perfect organic union of cabin and island, which will be the subject of part 2 of this essay.

Jager was a Slovenian born in Carniola, Austria in 1871. He graduated from the Vienna Polytechnicum in 1899 (the height of the Vienna Secession), and immediately went to work on city plan for the earthquake-ravaged Ljubljana. Jager was interested in the idea of a Slovenian national style in architecture, and his work was heavily influenced by Slovenian folk art and architecture. In 1901 as a captain in the Imperial Royal Government Service of Austria, he led the rebuilding of the Austro-Hungarian Legation which had been destroyed during the Boxer Rebellion. During his time in China, he developed a fascination with Asian culture, and he began his extensive collection of Japanese handicrafts, with a focus on metalwork, textiles, and wood-block printing (not unlike the similar passion of Frank Lloyd Wright).

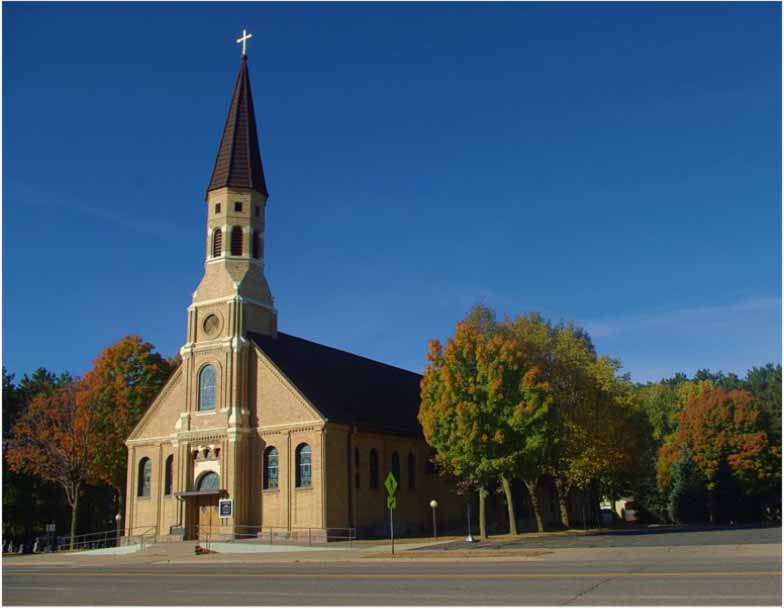

Jager immigrated to the United States in 1902, where he married Selma Erhovnic, a Slovenian artist he knew from Austria. Soon after his arrival, Jager published a booklet on church architecture, hoping to gain clients. Jager designed the Church of St. Bernard in St. Paul, and the Church of St. Stephen, in Brockway Township, Minnesota (both NRHP properties). St. Bernard's was one of the first reinforced concrete buildings in Minnesota. The structure is a unique with its Art Nouveau detailing, and is frequently referenced as an icon in a working-class district. The church at St. Stephen was designed for a Slovenian community from Carniola, and Jager devoted endless hours to managing every detail of the design and construction of the church and its interior.

In 1904 Jager built his home at 6 Red Cedar Lane, Minneapolis. Jager, with assistance from Purcell, designed Red Cedar Lane as a subtle but definitively landscaped street above Minnehaha Falls. He personally planned and maintained the eponymous red cedars, and he carefully chose a mix of conifers and deciduous trees that insured Red Cedar Lane was always green. Jager founded the Hiawatha Heights Improvement Association and encouraged all architecture in the area to achieve a harmony between structure and nature. In his design Jager was insistent that the neighborhood would preserve and enhance the natural beauty of the area, even to the point of presreving the natural contours of the land. Historian Larry Millett has said, "It would be hard to find a more beautiful street in the Twin Cities."

Following World War I, Jager went to Yugoslavia as a representative of the American Red Cross agricultural commission from Minnesota. The commission was headed by his brother, Major Frances Jager, who was a Catholic priest and a respected authority on bees. John Jager later received the Yugoslav Crown First Class as an award from Yugoslavian government. The Western Architect (of which Jager was an editorial assistant), described his intended work in words that so well capture the Prairie Architecture ideal we may suspect Jager himself wrote them (1918):

"Mr. Jager. whose professional abilities are varied and of a high order, will engage in a work unique in architectural accomplishment. Going from a country where the people as a rule think that any carpenter can "design" a cottage and therefore are satisfied with the "free plans" furnished by lumber dealers . . . he will demonstrate that a wide architectural knowledge fittingly applied can improve the livable qualities of even fifteen-dollar mudhuts."

Upon his return, Jager enjoyed a period of relative prosperity working for the conservative architectural firm of Hewitt and Brown, who has recently completed the Minneapolis Institute of Art as a staid Classical Revival structure . While working at Hewitt and Brown, Jager also was assisting Purcell and Elmslie in their work, largely out of his love of the progressive architecture designed by the firm. Jager refused, however, to take credit for the work he did at either. During these years, Jager formed a close friendship with William Purcell, and their voluminous correspondence reveals a dedication to Prairie School architecture and progressive ideals that continued strong well into the 1950s.

While Jager’s friendship with Purcell would last, his architectural career faltered. In 1928, however, Jager was laid off from Hewitt and Brown, and the crash of 1929 devastated his personal finances. Jager, under great financial distress, was forced to sell much of his personal art collection to his old employer and fellow Asian-art enthusiast Edwin Hewitt. The fate of his collection is an excellent example of how his own zeal for anonymity combined with misfortune led to his being forgotten. Upon his death, Hewitt himself donated his collection to the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, including Jager's unmatched collection of 1700 tsuba (sword guards). Subsequently the Hewitt collection has been on display, and formed the basis of special exhibits. Largely forgotten is that Jager personally was responsible for the quality and scope of much of the collection.

From the 1930s onward, Jager was never fully employed or able to exercise his skills and knowledge in a professional capacity. From 1933 to 1942 he served as the Superintendent of Public Works under the CWA and WPA programs. How he supported himself on the small salary of that job and through the years of underemployment remains unclear, although he received frequent and ongoing financial support from Purcell, whose family fortunes weathered the depression.

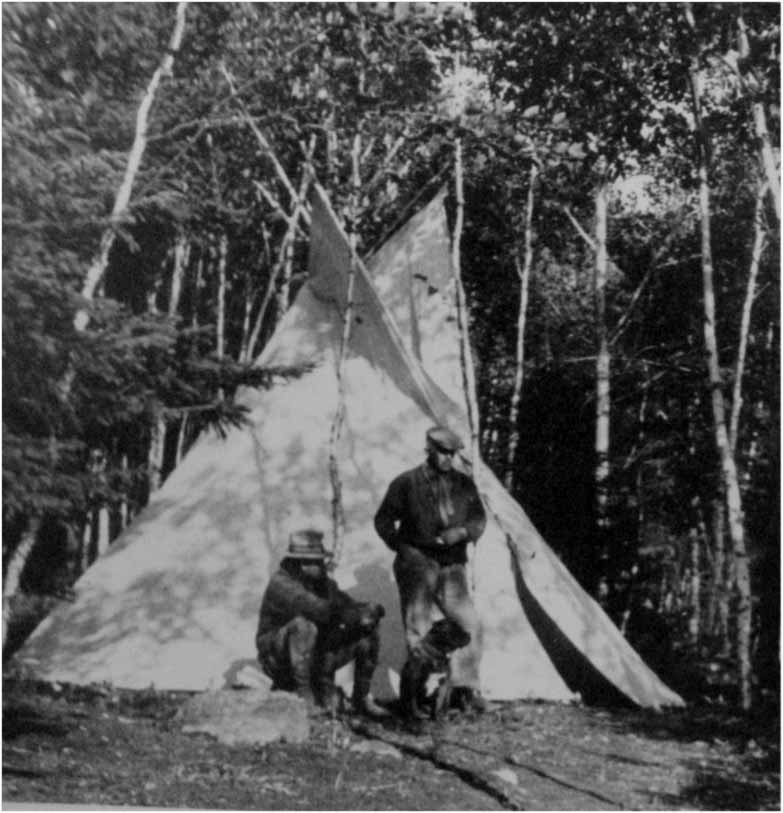

Jager occupied his time by participation in the intellectual community of Minneapolis, intense studies of linguistics, and as an editorial associate of the Northwest Architect. From the 1930s until his death at the age of 88 in 1959, Jager spent innumerable hours organizing the papers of Purcell and Elmslie. His near-obsessive attention to detail, matched by Purcell's similar organization of his papers, resulted in the spectacular Purcell collections of the Northwest Architectural Archive at the University of Minnesota. The bulk of Jager’s creative energies, however, went into the design of the cabin, trails and landscape of Wolf Island, where he spent each summer alone.

The breadth and depth of this intensely private man’s activities will, however, never be fully known. His eclectic library, as well as his own voluminous writings have largely disappeared (another factor in his relative anonymity). His widow Selma Jager tried to do some sorting, but in the end, most of his papers were burned on Selma's instructions. His remaining papers as well as a collection folk arts and crafts are curated at the Slovene Academy of Sciences and Arts.

Acknowledgment: Barbara Bezat (Northwest Architectural Archives), Richard Kronick and Mark Hammons provided much need assistance in navigating the voluminous William GrayPurcell papers as well as direction in understanding Jager and Purcell. Dr. Maja Lozar Štamcar, Senior Curator at the National Museum of Slovenia, has shared information about Jager’s work in

Ljubljana.

PHOTO CREDITS:

Fig. 1. John Jager (1918), William Gray Purcell Papers (N3), Correspondence - John Jager, Northwest Architectural Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries

Fig. 2. Church of St Stephen, St. Stephen, MN (ChipCity/Wikimedia Commons/CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Fig. 3. Church of St Bernard, St. Paul, MN (McGiever/Wikimedia Commons/CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Fig. 4. William Purcell (left) and John Jager (1928), William Gray Purcell Papers (N3), Correspondence - John Jager, Northwest Architectural Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gebhard, David, and Patricia Gebhard. Purcell & Elmslie: Prairie Progressive Architects. Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith Publisher, 2006.

Hammons, Mark. Guide to the William Gray Purcell Papers. St. Paul, MN: Northwest Architectural Archives, University of Minnesota, 1985.

Hammons, Mark. Purcell and Elmslie, Architects. In Minnesota 1900: Art and Life on the Upper Mississippi, 1890-1915, ed. Michael Conforti. Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 1984.

Millett, Larry. AIA Guide to the Twin Cities: The Essential Source on the Architecture of Minneapolis and St. Paul. Minnesota Historical Society, 2007.

After a successful academic career at St Cloud State University (Assistant Vice President for Research and Faculty Development, Professor of History and Archaeology), Richard M. Rothaus founded Trefoil Cultural and Environmental, a cultural resource management firm with vast experience in historic preservation and archaeology in Minnesota, South and North Dakota, as well as the Mediterranean (Corinthia, Greece; Cilicia Turkey; etc). His work with the preservation of historic landmarks has led Rothaus to the discovery of John Jager.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top