-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

St. Paul’s Character in St. Paul’s Cathedral

The first hint we have of the man later to become a great apostle and martyr Saint Paul was at the martyrdom of Stephen. The vicious stoning to death of Stephen is a chilling account to read, if you have a vivid imagination. So it will be easy to place Saul’s temperament for in spite of the horror, he stood and watched the slaughter with an unsettling cold calm. Thankfully, Saul is not the subject for today, Paul is. Paul, renewed by light yet unwavering in passion and strength of character. I was curious to see if Apostle Paul’s strong character or experience found expression in Sir Christopher Wren’s most valued work—St Paul’s Cathedral.

Surely I did not expect a literal translation of Paul’s experience or character in the fabric of London’s St Paul’s Cathedral though I imagine it would have been a powerful symbolic statement. In any case, my approach from the southern end of the cathedral presented me with little or no excitement at all to carry on. This, I guess is on account of the many structural distractions (leading on to the spot where the cathedral is) that the city of London presents. Also, on entering the nave, there was no ‘blinding light’ from above. The interior of the cathedral was considerably bright but far from blinding. The lights were evenly spread and indeed soft on the eye. To further dampen matters, I was informed that photography is not allowed on the interior of the cathedral. Suffice to say, the experience got off to quite a cold start.

Fig. 1: St Paul’s Cathedral, London. A view of the impressive dome and the southern façade.

Fig. 2: The ball and cross atop the cathedral dome. The cathedral dome is one of the largest in the world and it weighs about 65,000 tons.

Fig. 3: Statues of Evangelists atop the pediment of the southern transept.

Fig. 4: The nave of the cathedral near the transept crossing. The brilliant 19th-century mosaic work of the choir ceiling is clearly visible in the brightly lit interior.

The tone of my experience didn’t quite recover fully. With the luxury of taking photographs wrested from me, I was condemned to more time (than I usually have) of physical visual analysis of the building. This was perhaps a blessing in disguise for only at the instance of my sitting under the dome at the transept crossing did I begin to notice the intrinsic allure and Pauline nature of the cathedral interior. In a bit of a calculated disobedience, I went on to ‘steal’ some shots. Not paying much attention to the technical quality, I just wanted to get some photographs out in any case. Concealing the camera most of the time to take the shots, I guiltily justified my actions with a note-to-self that there were already hundreds of the cathedral photographs online anyway.

For sake of diligence, I must give a brief background of the character in question here—Saul of Tarsus, later Paul. A proud Roman and Pharisee, born a Jew in the Roman province of Cilicia. Saul was a scholar who studied religion and Jewish law in Jerusalem, and one of his teachers was the great scholar Gamaliel.1 In his time, he would have stood out from the lot on account of his education. Probably the most significant thing about Saul was that he was a staunch oppressor of the Christian movement. He was indeed on his way to Damascus to deliver letters that will authorise a full-scale battle against Christians when he encountered Christ in form of a ‘blinding light’. The encounter left him sightless and he could make his path only through guidance from his aids. His sight was later recovered in the city of Damascus under the care of a man called Ananias.2 Paul, now a transformed soul, was later to describe God as ‘unapproachable light” who no one has seen or can ever see.3 Renewed by this event, he went from firm prosecutor to brave propagator of the faith. The rest of the story as they say is history. Paul maintained a life of ‘suffering for Christ’. One that was not devoid of challenges and life-threatening situations. He was eventually martyred in Rome for bearing witness to the faith and thus became an idealized model for later Christians and arguably the most enigmatic of all the apostles.4

Fig. 5: One of the western towers topped with a pineapple. The pineapple is said to be a symbol of peace and hospitality.

Fig. 6: Squeezed on all sides yet it exhibits the resilience, boldness and true character of an evangelical masterpiece. Here St Paul’s Cathedral appears to be sandwiched between two modern structures, this is however an optical illusion occasioned by my positioning for this shot.

Fig. 7: St Paul’s column. The marble column is topped with a gilded statue of St Paul. Positioned in the northeast yard of the church compound, it is the location where Williams Tyndale’s New Testament was burned because it was in English.

Fig. 8: Closer details of the base of the column.

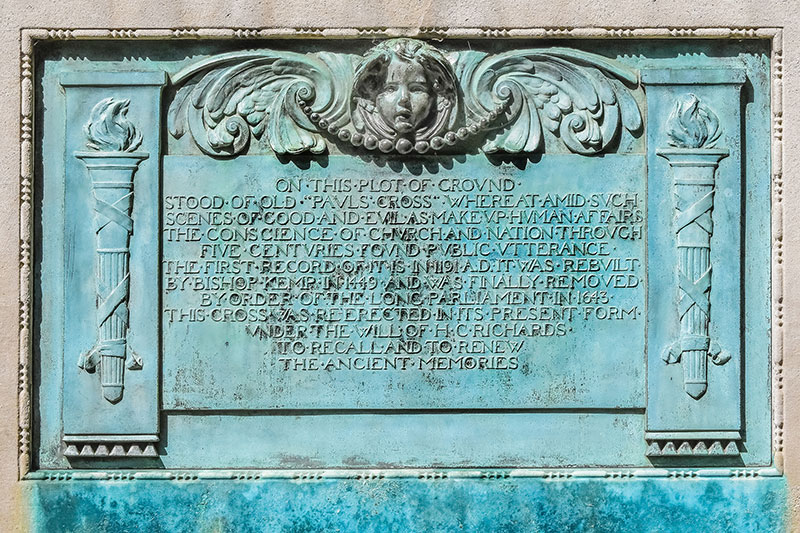

Fig. 9: A plaque tells of the history and significance of the spot where the column is found. Amongst other information, it relates that “On this plot of ground stood of old, Paul’s cross."

Fig. 10: Gilded statue of St Paul in the northeastern corner of the church yard.

Fig. 11: A view of Paul’s Column and a part of the cathedral dome.

St Paul’s Cathedral: Bearing the Marks

For the sake of brevity, I will restrict myself to only a few thoughts here. The idea of a direct relationship between Apostle Paul’s personality and St Paul’s Cathedral physical structure is of course on first thought ludicrous. However, we must constantly be reminded of the danger there is in limiting our minds from exploring alternate and sometimes marginal insights to our study of architecture. One is unclear if Sir Christopher Wren considered the personality of the Apostle Paul as he designed the new London cathedral (however covertly). I am not convinced that he did. If he did, I will assume it was not too profoundly. It seems more logical that mathematics and geometry was his inspiration—after all, Sir Wren was an astronomer and mathematician, technically never trained as an architect. Further, if indeed in the Baroque canons, there is such a practise of directly translating natural forms into actual architecture in an act of mimicry, then in the case of St Paul’s cathedral, I fear we may have something of a dreadful building. I have here no intention of being blasphemous but on recorded accounts and by today’s standards (possibly by ancient standards as well) Paul of Tarsus was not a very attractive man. Wren may find nothing of appeal in Paul’s physical appearance to translate to his architecture I will presume. The same cannot be said for Paul’s ecclesiastical journey however. I am bold to conclude that should Christopher Wren have inquired into Paul’s ecclesiastical life for a design inspiration, he would not have had to search for long. That said, in an 1882 publication, Phillip Schaff refers to the apocryphal Acts of Paul and Thecla (AD 170) as the earliest written description of the Apostle Paul. He was described as "bald-headed, bow-legged, strongly built, a man small in size, with meeting eyebrows, with a rather large (or long) nose."5 Also, in the scriptures one will recall the line referring to Paul’s physical appearance as unimpressive.6 Further, I would imagine the recurring danger and hazards of his profession will constantly dispose him to a less than attractive appearance. It is reasonable to assume that if a frenzied crowd stoned and dragged a person to the point where they were sure he was dead, as it happened to Paul in Lystra in the Acts. 14: 19, he would not look like very much thereafter. A man who has endured much scarring in the name of the gospel in those early days will leave very little to our guessing eyes. Perhaps the remarks in his letter to the Galatians referred to his scars, bruises and injuries as much as they did to a symbolic identification with ChriSt “I bear on my body the marks of Jesus”.7

Therefore again I understand how absurd it may appear as to even consider the thought of any expression of Paul’s physical outlook and/or experience in the building of St Paul’s cathedral. Experts of Wren and his works may surely cringe at the slightest suggestion that such may be the case of the master’s design thought process, nevertheless, I am persuaded that there may be a thing or the other to learn from approaching St Paul’s cathedral from this point of view. Sir Christopher Wren has an amazing record of building 52 churches in London through his career and being famed to be one of the most distinguished promoters of the English Baroque, surely there must be some type of allegiance to the practise of figural representation and the craft of incorporating symbols in design. Wren had travelled to Paris where he met the great Baroque sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini in 1665. This must have had an ideological impression on Wren as his later works showed clear articulations of both Bernini and Francesco Borromini’s Italian architectural styles carefully tempered with the more sober and strict classical style of Inigo Jones.8

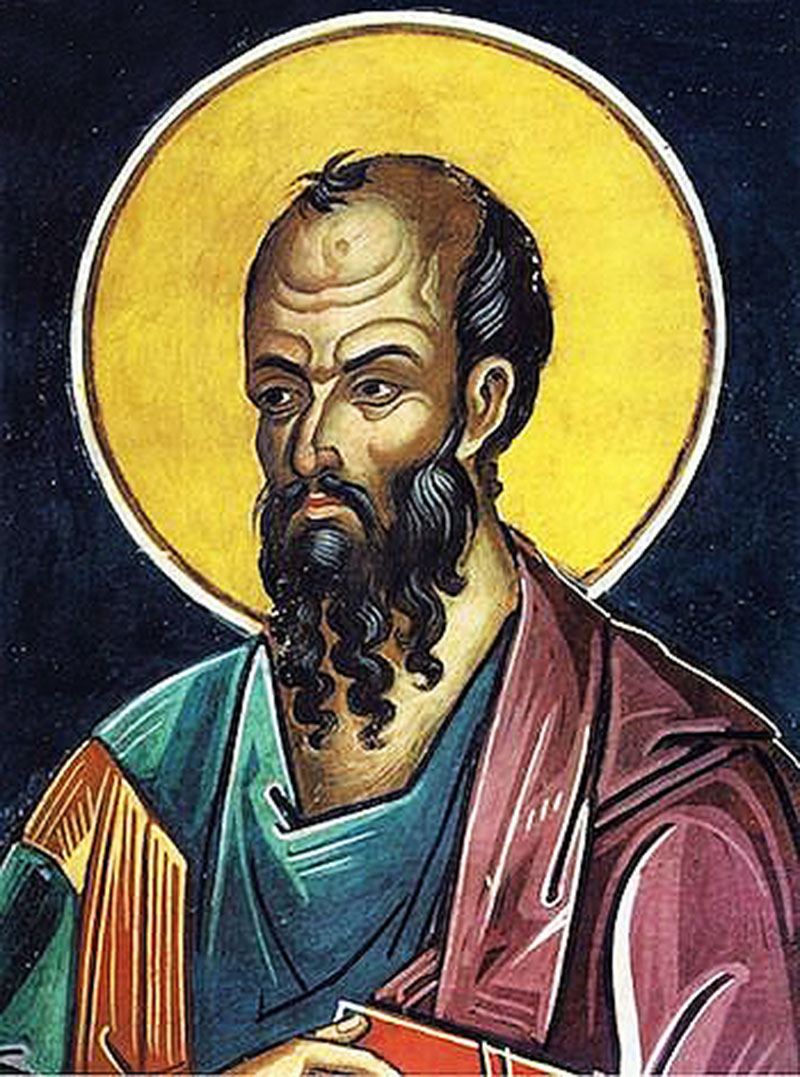

Fig. 12: A 3rd-century medallion showing the Apostles Peter and Paul. Here is one of the earliest visual representation of St Paul. Paul is to the left, one will notice his bald head. This gives some credibility to the apocryphal material. Source: Sacred Museum of the Vatican Library

Fig. 13: An Orthodox icon of Apostle Paul. Source: Icon of 16 century, Mount Athos Monastery of Stavronikita.

Fig. 14: That’s me ‘photobombing’ this shot I secretly took in the choir area of St Paul’s Cathedral around the baldacchino.

Fig. 15: Ceiling décor in the southern transept.

Fig. 16: Ornamental piece with vegetal and figural designs.

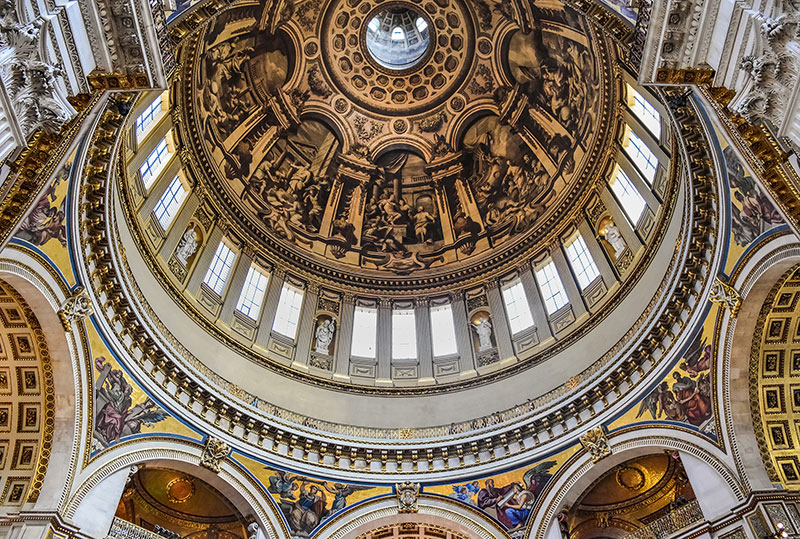

Thus, in visually analysing the interior, my attention is drawn to the paucity of colours on the interior of the cathedral dome. As we saw in my last post, no artist will falter in the opportunity to render the interior of a dome in the most vibrant colours that capture the transcendental mood we like to experience when we think of heaven. Most domes present a wonderful tone of joy and beauty, sometimes in the most innocent colours—but, what are we to make of the English painter James Thornhill’s 1715 paintings in the dome of St Paul’s? Without hesitation I am inclined to equate the medium of rendition to the austere nature of Paul. I see this lone brown tone of the murals as a representation of the singularity of Paul’s purpose after the experience on the road to Damascus. The mural captures key experiences of Paul’s ministry and clearly avoids any distractions. One is compelled to focus on the stories of Paul’s life related in the work. Though records show that Sir Wren had intended to use mosaic for the finishing of the interior of the dome, still the ‘sombre’ painting agrees with the general low tone of ornamentation in the cathedral. Queen Victoria is said to have complained at one point that St Paul’s was too ‘dull, dingy and undevotional’. The vivacious display of mosaics we see today in the choir ceiling of the cathedral was designed by William Richmond and was installed as a response to the queen’s remark.9 The baldacchino was designed by Stephen Bower and it represents something of Wren’s original intentions—it too rendered in deep colours, though partly gilded and so beautifully crafted but nonetheless sombre in every nature imaginable.10

Speaking of Symbols—The Blinding Light

While fully understanding the challenges of designing for 17th-century English royals and aristocrats particularly at a time when London had suffered a most damaging blow in the 1666 Great fire and a renaissance was priority for royals like Charles II. Even Sir Wren’s design of the cathedral was rejected twice. I will leave this discussion with a thought here. How symbolic would it have been if Sir Wren borrowed the ingenious concept of the oculus from the Pantheon in Rome? For what purpose we may ask? Imagine if a strong and directional light came into the cathedral through the oculus, outshining the ambient light. Crafted such that as the sun rises in the east, it shoots a strong beam of light that hits the nave towards the western end and gradually moves along the nave towards the great altar illuminating the inner dome and creating a bright spotlight on the star in the middle of the cathedral transept at noon thereafter moving further towards the altar as the day proceeds. Seeing that the experience of Saul on the way to Damascus is so critical to the ‘creation’ of the person we know as Paul, what can be more symbolic of the redemption of Saul and his translation to Paul as he is drawn closer to God (symbolised by the altar) through light. The moving of the light through the nave may then represent the story of the life of Paul as he was initially far off and being transformed by the mystery of the great light, he found a straight path through the same light unto God. The movement of the light in the cathedral will then serve as a reminder of Paul’s journey in faith and conversely a recurrent call to all to come to Christ who is seen to be the light of the world.

Sure this will require dramatic changes to the structure of the dome. Most post-Romanesque churches often aspire for such vertical height at all costs hence the prospects of the thoughts expressed here are rather dim—still how glorious a sight it will be to behold the great light appearing every day inside the cathedral and symbolically showing the path for those who are yet far off to draw near. Just like it did for Paul in the early years.

Fig. 17: The (inner) dome of St Paul’s Cathedral. The current painting is an 1853 recreation of James Thornhill’s work based on the life and ministry of St Paul.

Fig. 18: A view of the cathedral’s inner dome plus mosaic pieces on the triangular spaces between the arches of the dome columns. The mosaics feature depictions of Old Testament prophets like Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel etc. Designed by Alfred Stevens and George Frederic Watts and was installed 1864–1893.

Fig. 19: A view of part of the cathedral’s inner dome.

Fig. 20: Details of the mural inside the inner dome. Here Apostle Paul is shown in Malta after a shipwreck.

Fig. 21: A view of the cathedral’s choir showing the brilliant 19th-century Mosaic work on the choir ceiling. Also the oak wood choir stalls can be seen on both sides.

Fig. 22: Details of the ceiling art in the quire of St Paul’s Cathedral. The baldacchino is seen further in.

Fig. 23: Details of the baldacchino in St Paul’s Cathedral.

Fig. 24: The baldacchino surmounted by a gilded statue of Jesus.

Fig. 25: The transept crossing area directly under the dome. The floor motive resembles a sun or star with rays around it. In the very center is a copper plate with perforation in it. The pattern made by the perforations appear to be two interlocked diamond shapes.

Fig. 26: A view of the southern transept. Interestingly, a strong light enters through a clerestory window from the right and hits the sculptural pieces on the lower left, drawing our attention to the work.

Fig. 27: Photo of the interior of the Pantheon showing the effects of light entering the space through the oculus. Source: http://pictureofperfectyouth.blogspot.com.ng/2015/07/vatican-city-and-rome.html

A Note on St Albans

Away from London, I venture a few miles north to a town less familiar but nonetheless of great importance to church history in Britain—St Albans. Here we find the St Albans Cathedral, named after the very first British martyr. A short note on Alban is noteworthy here. Alban is believed to have lived during the 3rd century in the old Roman city called Verulamium, located in the valley below the present cathedral.

In the early times when Christianity was still a forbidden religion, Alban gave refuge to a Christian priest called Amphibalus who was fleeing for his life. Alban, was so moved by the priest’s faith and courage asked that he be taught more about this faith. In time being now inspired by his new faith, Alban crafted a plan for the priest to escape the authorities when they eventually came for him. Alban exchanged garments with the priest allowing the priest to make his escape. The Roman authorities arrested Alban instead, and he was brought before the city magistrate. In his trial, Alban publicly declared his newfound faith and refused to sacrifice to the Roman gods. Consequently, he was sentenced to death. Thus, Alban is brought out of town and made to walk up hill (to the site where the cathedral now sits) where he was beheaded, making him the first British martyr. A simple church was erected over his grave making it the oldest site of continuous Christian worship in Britain.11

Fig. 28: Western façade of St Albans cathedral. A hint of the old tower can be seen to the left.

Fig. 29: A view of the western and older southern facades. The southern walls are mostly of the Early English and decorated era with some 19th-century repair work done on the buttresses of the southern facade.

Fig. 30: A view of the western front designed and built by Lord Grimthorpe in 1880 replacing a fine 15th-century window and much to the disapproval of many.

Fig. 31: A view of the old Norman tower and the much newer southern transept of the St Albans Cathedral.

Fig. 32: Stones and tiles from the ancient city of Verulamium used to (re)build portions of the cathedral in the late 11th century.

Fig. 33: Vestiges of the Early English legacy of the cathedral: pointed arches in one of the cathedral’s isles.

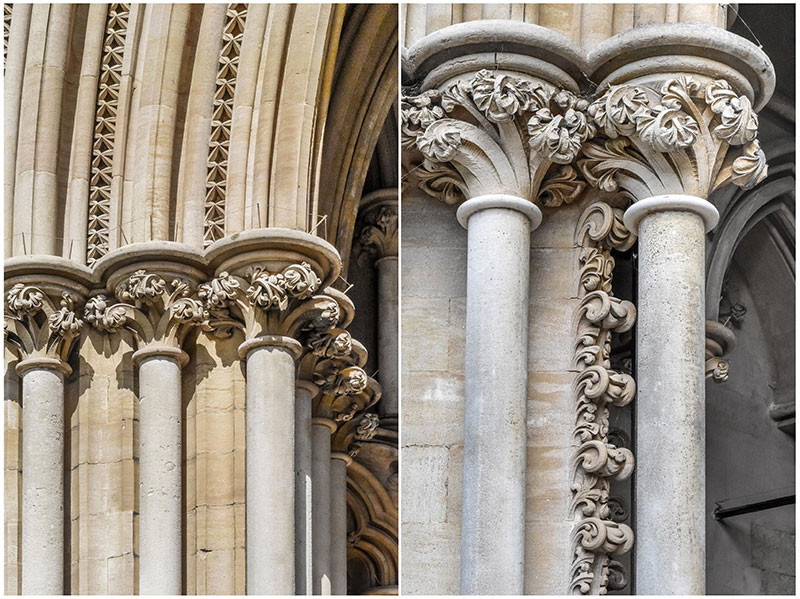

Fig. 34: Ornate floral patterned capital in St Albans cathedral.

Fig. 35: Solid matter comes alive taking organic form and yielding to the mason’s chisel—such beautiful example of the masons’ work. Columns from the St Albans cathedral.

Several historians bare testament to the early church erected in honour of St Alban. Bishop Germanus of Auxerre recorded his visit to St Alban’s church in 429 AD. In the early 8th century, the chronicler Bede, in his work Ecclesiastical History, also mentioned the church’s beauty and called it a befitting piece worthy of Alban’s martyrdom. It was, however, Abbot Paul of Caen that would bring much significance to the structure in 1077 by rebuilding the church in the Norman style and erecting the great tower from bricks and tiles from the ruins of Verulamium, the old Roman town where Alban lived.

The church today is a mixture of architectural styles on account of its long years. It boasts of one of the longest naves in all of the United Kingdom. 85 meters (276 ft) of absolute history and a symbol of consistency. Though several effigies of St Alban (both old and new) are found in the cathedral, the most important item may well be the shrine chapel of St Alban, believed to house the collar bone of the saint. The ornately carved marble shrine is a beauty. Demolished after the Dissolution of Monasteries in the 16th century during the reign of Henry VIII, the shrine was reconstructed in 1872 from over 2000 small broken pieces found in the chapel. The shrine speaks of persistence very much like the cathedral. Covered in red and gold silk, the red is said to represent the blood of St Alban and the gold, his crown in heaven. The triangular shapes at the base of the silk cloth represent the letter ‘A’ for Alban, and in the shapes one will find embroidery of the different flowers that would have been in bloom on the hill in June when Alban climbed to meet his fate.

The high altar screen, which features a rather ornate and detailed sculptural display, draws one’s attention but above everything else, I find the ornamentation of the ceiling in St Albans Cathedral a brilliant demonstration of artistry and the finer crafts. Every area of the cathedral presents a different style and statement from different eras. From the painted flat wooden panels of the nave to the ornately decorated ceiling of the tower, the lovely Presbytery ceiling paintings and the gorgeous chantry fan vaults, looking up inside St Albans does reward you with a pleasant show of ceiling art. Further, the finishing of St Albans Cathedral ceiling does give a hint of what is to be expected in the whole of the UK.

Fig. 36: A montage art work in the nave of the St Albans Cathedral tells the story of the building of the cathedral during the time of Abbot Paul of Caen in the 11th century.

Fig. 37: A view of St Albans cathedral nave with portions of the northern wall showing in the background.

Fig. 38: A beautifully crafted baptismal bowl in St Albans cathedral with a suspended top-piece hovering above.

Fig. 39: The High Altar Screen—a graceful display of sculptural arts in the quire of St Albans cathedral. The screen features the statue of Christ, saints and notable people in the history of British Christianity. One writer says it is a feast for the eyes as the priest invites worshippers to join “with angels and archangels and all the company of heaven” as they draw near to share in Holy communion.

Fig. 40: The shrine of St Alban in the center of the chapel. Covered in red silk and mounted on an ornate marble podium, it is believed to house a relic of St Alban. Demolished during the Dissolution and rebuilt in 1872.

Fig. 41: Another view of St Alban’s shrine. The rose pattern on the shroud was designed by Suellen Pedley. This rose motive is a reflection of the chronicler Bede’s reference to Alban as the ‘rose among martyrs’.

Fig. 42: The Stone Nave Screen of St Albans Cathedral was built by Abbot Thomas De la Mare to separate the lay areas from the monastic part of the church. The statue we see on the screen now are newly sculpted 2015 pieces. They are statues of seven Christian martyrs. St Alban is in the middle with a blue cape holding a sword. The original statues were destroyed during the Dissolution.

Fig. 43: A brilliant example of what is to be seen in cathedrals in the UK. Excellently ornate vaulted ceilings.

Fig. 44: An ornate screen wall near the Shrine of Amphibalus in the quire of St Albans Cathedral.

It is commonly agreed that the English went through three Gothic phases known as Early English period (ca. 1190–1300), Decorated period (ca. 1250–1380) and Perpendicular period (ca. 1350–1550). It will appear, however, that even at the peak of their Decorated period, they will not match the French in ornamentation of their cathedrals. This may be deliberate however. Van Eck (2012) argues that the English hierarchy and head of the church were anxious to develop a formal vocabulary that would break away with medieval traditions, but not too much. They proposed that their churches should not look too much like contemporary church design in Italy or France, for obvious reasons.12 What the British lack in figural ornamentation of their cathedral walls, they made up for it in their luxurious exhibition of ceiling art and dynastic shield displays.

Fig. 45: The old Tower ceiling of St Albans Cathedral—repainted in 1952 to the original 15th-century details. The Red and White roses depicted is said to be associated with the Houses of Lancaster and York, respectively. This art piece may be in commemoration of the battles of the war of the roses fought in St Albans in 1455 and 1461.

Fig. 46: Details of the tower ceiling art.

Fig. 47: The quire ceiling with 14th-century paintings featuring the arms of Edward III and his sons together with those of his supporters. Religious symbols are also featured.

Fig. 48: The Great organ in the quire of St Albans Cathedral. In the middle is a statue of St Albans.

Fig. 49: Famed to be the largest of its kind in the UK, the presbytery ceiling is a 13th-century wooden ceiling hanging above the high altar in St Albans cathedral. Originally built in 1280 with oak, it was later redecorated by Abbot Wheathampstead in the 15th century with badges of patron saints and family shields of other patrons who contributed money to the repair of the cathedral.

Fig. 50: Another view of the Presbytery ceiling work.

Though both the French and British love and have a long history of the use of family crests and badges, patronage and donations to church building projects was met with a more generous compensation in Britain as the practise of fitting and displaying family shields is clearly more noticeable in English cathedrals.

1 Wilson, Larry L., Saul of Tarsus—Good Heart Wrong Head. Ebook. WUAS, 2002.

3 Eastman, David L. "Introduction." In The Ancient Martyrdom Accounts of Peter and Paul, Xvii-xvi. Society of Biblical Literature, 2015.

5 Schaff, Philip. History of the Christian Church, Apostolic Christianity AD. Ebook. CCEL, 1882.

8 Shafe, Laurence. The English Baroque in Art and Architecture. Ebook. http://doczz.net/doc/4775356/13-wren-and-the-english-baroque---art-history---by-lauren...

9 Cornwell, Helen & Taylor, Matthew. St Paul’s Cathedral ed., Esme West (London: Scala Arts & Heritage, 2014), 29.

11 Who was St Alban? 2013.

12 Van Eck, Caroline. Figuring the Sublime in English Church Architecture 1640–1730. Ebook. Brill, 2012.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top