-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

What Has Architectural History Done About Recent Immigration Policies?

Shortly after coming to power, United States President Donald Trump signed an executive order on January 27, 2017, that banned the entry of citizens from Iraq, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen. Professional organizations for architectural historians, including the College Art Association (CAA) and the Society of Architectural Historians (SAH) immediately released statements criticizing the ban, and many universities did the same declaring their commitment to the protection of immigrant and international students on their campuses. However, the Supreme Court’s decision to uphold a slightly revised version of the ban on June 26, 2018, despite massive protest, and additional anti-immigration policies during the time in between, as well as the continuing decline of civil liberties around the world have strengthened the realization that fundamentals such as human rights, academic freedom, and nondiscrimination cannot be taken for granted.

I would like to express my serious concern about the recent immigration policies, such as those known as the “Muslim ban” and “family separation” that restrict the entry and impair the livelihood of individuals from certain countries to and in the United States. As an academic worker of a university in the United States with a large number of international students and scholars, I am deeply disappointed because such decisions send a message to the world that this country is not a hospitable place for academic pursuits. A good percentage of my students and co-members of professional organizations come from countries outside of the United States and make invaluable contributions to the writing and teaching of architectural history.

You may ask, with a sense of cynicism, what good is declaring the obvious, signing one more petition, or posting one more time on social media. Yet, this is precisely the mood that helps the status quo. If observing the fast decline of civil liberties and the governing system change in Turkey, my country of birth, is of any guidance here, I can say that one should not be too assured about the strength of former civil rights gains, or assume that long-standing institutions will always be able to protect basic democratic values. Moreover, I have come to realize that sometimes the obvious is not actually as prevalent as we think even in our own immediate surroundings, and that words are emptied out. This would be true for the assumed recognition of some of the previous critical work for civil right movements or architectural scholarship. For instance, if I had to write a vow for architectural historians as a symbolic gesture against the recent immigration policies, it would have read something like this: “We declare that we will be committed to the study of a connected world, global understanding of architecture, open exchange of ideas, religious and cultural difference, inclusive scholarly pursuits and open access to knowledge. As architectural historians, we will continue to conduct research on the work of and for immigrants, exiles, refugees, and foreign nationals. We are committed to advancing scholarship on architects from all countries who have contributed to the world of architecture. We will continue to critically expose architects’ involvement in past atrocities such as Japanese internment camps, German concentration camps, or slave markets. We call on all architects to refuse to be complacent with such practices today.” However, as I was imagining this vow would be quite commonsensical, memories rushed to my mind of the moments over the course of my becoming and working as an architectural historian when I was exposed to the trivialization and repudiation of scholars (including myself) who try to move in this direction by contributing to postcolonial theories, alternative modernities or intertwined histories.

If silence and the dying out of critical speech are conditions that enable autocrats, atomization is another. There must be many more architects, historians and intellectuals out there than the ones I already know, who are working on architecture’s role and critical potential in anti-immigration and national superiority sentiments, but their lack of visibility is predicated on and perpetuates the very problem at hand. It is for this reason that in this post I do want to mention a few points about how my work tried to produce analytical lenses and vocabulary to contest discriminatory policies, but beyond that, I also would like to invite all readers to post their own work, sources of inspiration or frustrations. Atomization disables solidarity. Please do write so that we are not hidden from sight.

Let me start, then. One premise behind sanctions such as the Muslim ban that categorize a vast number of individuals as potential threats based on their national citizenship is the assumption that their countries of origin are inherently different from and essentially in conflict with the United States. This premise is nothing but a continuation of the “clash of civilizations” theory, which was first coined by the Orientalist author Bernard Lewis, and popularized by Samuel Huntington and the conservative media. So much ink has been spilled to argue that the planet is divided into some isolated and self-contained civilizations. However, upon looking closely, architectural historians have found enough evidence to contest this claim. We can therefore contribute by developing the vocabulary and unearthing the examples of intertwined histories, so that we have the words and evidences to challenge the premises that make the Muslim ban popular. An additional irony of this ban is that most of these “other” countries have been recognized as “cradles of civilization” where architectural wonders of the world heritage once stood, such as the cities of Isfahan, Samarra or Shibam. By writing the architecturally relevant histories of buildings designed during the twentieth century, historians can also abolish the Orientalist assumption that the architecture culture stopped to evolve in these countries during the modern period. These were among my intentions in setting the theoretical framework in Architecture in Translation: Germany, Turkey and the Modern House (Duke, 2012), which offered a way understand the global movement of architecture, by tracing transportations between places and their transformations in new destinations. While contesting the clash of civilizations theory, the book was not meant to turn a blind eye to the imperial and nationalist attitudes that strengthened the claims to civilizational incommensurability on both sides of the ideological divide. Instead, it critically exposed the geopolitical hierarchies and nationalist anxieties, and showed evidences against irreconcilability, so that the clash theory does not become a self-fulfilling prophecy. It called for a new culture of translatability from below and in multiple directions for the sake of global justice and true cosmopolitical ethics that has long been rightly suggested as a prerequisite for perpetual peace.

I have also come to think that the word "citizenship" should not be taken for granted or put on a pedestal as if its intellectual potentials have been accomplished. The vulnerability of noncitizens is exposed by sanctions such as the family separation and the Muslim ban, but this is not my entire point. Far from being subject to discrimination due to national laws, noncitizens are also only barely protected by international laws—a condition that exposes the insufficiencies of the current human rights regime. As we witness today the biggest refugee crisis since the Second World War, this condition has become even more apparent. For my recent book Open Architecture: Migration, Citizenship and the Urban Renewal of Berlin Kreuzberg (Birkhäuser, 2018), I conducted many oral histories with former refugees and guest workers. Listening to their stories while watching the recent global developments, I was often confronted with the fact that the forces that had shaped the experiences of one of the most discriminatory periods in history (covered in the book) are indeed continuing today. These not only include spatial aspects such as the condition of asylum camps and refugee dorms, and the lack of decent housing for the immigrants, or habitual practices such as state brutality and hostility toward migrants, but also structural challenges such as rightlessness of the stateless and crises of citizenship categories. Given the fact that the definition of human rights is preconditioned on being a citizen of a nation-state, Hannah Arendt and Giorgio Agamben have already conceptualized the status of the refugee as the limit condition of modern international legal order. Ever since the declaration of rights with the people’s sovereignty revolutions in the late 18th century, the link between natural and civil rights, “man” and “citizen,” and birth and nationhood has continued to define human rights, making it impossible to have rights without citizenship. “The refugee must be considered for what he is: nothing less than a limit concept that radically calls into question the fundamental categories of the nation-state, from the birth-nation to the man-citizen link, and that thereby makes it possible to clear the way for a long overdue renewal of categories” (Agamben, p.134). As a matter of fact, the concept of citizenship has been in constant evolution for centuries, as the former slaves, women and colonial subjects gained citizen rights. It ought to remain changing as refugees and global migrants continue to remain rightless, and as sanctions such as the family separation and Muslim ban frequently throw the world into crisis. The stateless constantly reminds us of the “long overdue renewal of categories” and the deficiencies of a world divided into nations. For this reason, the ultimate openness in architecture is the hospitality toward the stateless.

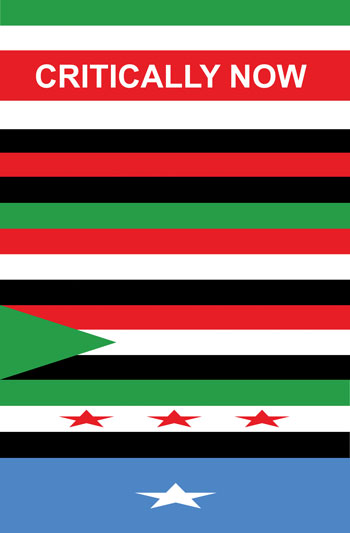

Launching logo of the “Critically Now” series in the Department of Architecture at Cornell University. (Critically Now team: Esra Akcan, Luben Dimcheff, Jeremy Foster, George Hascup, Aleksandr Mergold, Caroline O’Donnell, Jenny Sabin, Sasa Zivkovic. Logo design by: Caroline O’Donnell)

Esra Akcan is an associate professor in the Department of Architecture, and the director of the Institute for European Studies at Cornell University. Akcan's scholarly work on a geopolitically conscious global history of architecture and urbanism inspires her teaching. She is the author of Landfill Istanbul: Twelve Scenarios for a Global City (2004); Architecture in Translation: Germany, Turkey and the Modern House (2012); Turkey: Modern Architectures in History (with S.Bozdoğan, 2012); and Open Architecture: Migration, Citizenship and the Urban Renewal of Berlin-Kreuzberg by IBA-1984/87 (2018). She has received numerous awards and has authored more than 100 articles on the intertwined histories of Europe and West Asia, critical and postcolonial theory, architectural photography, migration and diasporas, translation, and contemporary architecture. These works offer new ways to understand the global movement of architecture, and advocate a commitment to a new ethics of hospitality and global justice. Akcan has also participated in exhibitions by carrying her practice beyond writing to visual media. Akcan was educated as an architect in Turkey and received her Ph.D. from Columbia University.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top