-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

2018 Edilia and François-Auguste de Montêquin Senior Scholar Fellowship Report

Jul 29, 2019

by

Dr Laura Fernández-González, Senior Lecturer in Architectural History, School of History and Heritage, University of Lincoln (UK)

Dates: April–June 2019

Locations: Havana and Santiago de Cuba, Cuba

The generous support of the 2018 Edilia and François-Auguste de Montêquin Senior Scholar Fellowship offered by the Society of Architectural Historians has enabled me to undertake extensive archival research and fieldwork in Cuba in April–June 2019. My project for the Montêquin fellowship, ‘Architecture, Empire and Public Rituals in Early Modern Havana and Santiago de Cuba’, explores architectural and urban development in both locales through the lens of public rituals with a view to comparing similar processes in other cities, for example, Seville. Public rituals had a major impact on the urban and architectural development of early modern cities and there has not been any study to date that explores comparatively the impact of empire on the built environment and ritual life of the port-cities that received and saw the departure of convoys to and from the Americas. The research I have undertaken as part of this fellowship forms part of a book project tentatively entitled Entangled Imperial Cities in the Early Modern Iberian World that examines architecture and ritual not only in Havana, Santiago de Cuba and Seville (i.e., some of the main city-ports in Spanish-American navigational route) but also compares analogous processes in Lisbon and Old Goa (i.e., on the Portuguese-Indian navigational route).1 Lisbon and Old Goa were the two main Eurasian city-ports from which the convoys to and from India departed and arrived. The impact of empire can be arguably charted through an analysis of the architectural development and ritual life in these locales.

The Portuguese philosopher and historian Damião de Góis (1502–1574) claimed that the cities of Seville and Lisbon were ‘the queens of the ocean’, a metaphor that underscored the role of both ports on the main navigational routes within the Iberian world.2 The strategic location of Goa (now Old Goa) in the Indian Ocean was considered crucial for the Portuguese trade in India, so much so that the city was called the Chave de Toda a India (the Key to All India).3 In the same vein, the significance of Havana to the Spanish imperial enterprise was crucial for it provided access to New Spain; the regidor of Havana, José Martín Félix de Arrate, in his famous manuscript of the history of the city of 1761 called Havana the Llave del Nuevo Mundo (the Key to the New World).4 The wealth of the Americas (and the world) travelled through Havana en route to Seville and to New Spain. Because Santiago de Cuba was the main port on the island before the seat of government moved to Havana in the sixteenth century, charting its architectural development is also useful for comparative analysis. The wealth of India and the East travelled in convoys from Old Goa towards the famous market in Lisbon, while from Goa goods were also redistributed elsewhere to Asian ports (and vice versa). This book compares the impact of empire and transoceanic communication on the architectural development and ritual life of some of the most significant city-ports of the early modern Iberian world. The theoretical framework of this project adheres to the practice of ‘connected’ or ‘entangled’ architectural histories, a methodology that crosses the boundaries of modern nation-states and aims to de-centre our understanding of the early modern world. Thus the fieldwork and archival research I was able to undertake as part of the funded project by the Society of Architectural Historians has been pivotal for the advancement of my Entangled Imperial Cities book project. It has also allowed me to include some considerations on the built environment of early modern Havana in an article entitled ‘Architectural Hybrids? Building, Law and Architectural Design in the Early Modern Iberian World’ which is forthcoming with Renaissance Studies.5

Figures 1 and 2. Interior of the Church of the Espíritu Santo, considered the oldest surviving religious structure in Havana. This is a small yet fascinating church, which was built in the seventeenth century (and restored thereafter). Observe the design of vaulting on the apse, which echoes examples found elsewhere in the Iberian World. Photographs by author.

I spent the vast majority of my time visiting buildings and researching in archival and library repositories, for about six weeks in Havana, and one week in Santiago de Cuba. In Havana I explored the spaces and buildings within and outside the colonial city wall. I also undertook extensive archival research in the rich cartographic collections and consulted the Actas Capitulares of the Concejo de San Cristóbal de la Habana (the records of the local council of Havana), both of which are kept at the Archive of the Oficina del Historiador de la Habana. The Actas meticulously record the reception of governors, the festival culture of the city and the buildings erected in the city (including houses, palatial structures, as well as churches, convents and monasteries). The warm welcome and support from all staff members at the Oficina were instrumental in the success of my project. I am extremely grateful to Dr Eusebio Leal Spengler, Director of the Oficina del Historiador de la Habana, for hosting my research stay as a Visiting Scholar; his kind support enabled me to conduct research in archives and libraries in the Isle of Cuba.6 In the Archive at the Oficina I was able to chart the local council records concerning the built environment and public rituals between 1550 and 1654 approximately, but I have consulted (or obtained copies of) many historical records from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. I also benefitted from the generosity and kindness of staff at the Archivo Histórico Nacional and was able to further explore the records pertaining particularly to convents and monasteries in Havana and also Santiago de Cuba. In Santiago de Cuba, on a shorter trip lasting one week, I was able to greatly advance my work at the Centro de Documentación of the Oficina del Conservador, which has a rich collection of architectural plans, and reports on domestic and religious architecture. Research in archives and libraries will have a positive impact on my book project. In the Library of the Oficina del Historiador I was able to consult a wealth of publications; the literature on architectural history of Isle and Havana in particular is rich. As part of my research I did extensive fieldwork in both cities, particularly Havana, but also Santiago de Cuba.

The architecture of all ages in Havana is stunning, regardless of the contrasting state of conservation; the city can pride itself on the rich architectural heritage it possesses that ranges from sixteenth-century forts to delightful Art Deco buildings or residential architecture that boasts modernist design. Santiago de Cuba, a smaller city, also boasts impressive buildings. The majority of my photographs focus on colonial architecture. I spent the greater part of my time in these buildings and spaces as the images below illustrate.

Figure 3 Dome (interior) at the Cathedral of Havana. A fine example of Havana’s baroque. The Cathedral was erected in the late eighteenth century on the grounds of the former Society of Jesus buildings in Havana. Photograph by author.

Figure 4 Cloister of the old Colegio Seminario de San Carlos in Havana. Founded originally in 1689, the School (Colegio) also occupies the grounds of the Jesuit properties in the city (and is adjacent to the Cathedral of Havana). The Jesuit building was completed in 1767, the year in which the Society of Jesus was suppressed from the Isle of Cuba (and the rest of the Spanish empire). The building underwent important reforms thereafter. Photograph by author.

Figure 5 Vista of the Capitanes Generales Palace (foreground), the attic of the Segundo Cabo Palace and the Cabaña Fortress at the far end. The Plaza de Armas is found to the right-hand side of the Capitanes Generales Palace. Photograph by author.

Figures 6 and 7 Patio and Main Hall (respectively) of the Segundo Cabo Palace in Havana. The building recently restored as a museum is a fine example of Havana’s neoclassical eighteenth-century governmental building. The palace is located in the Plaza de Armas and adjacent to the Castillo de la Real Fuerza. Photographs by author.

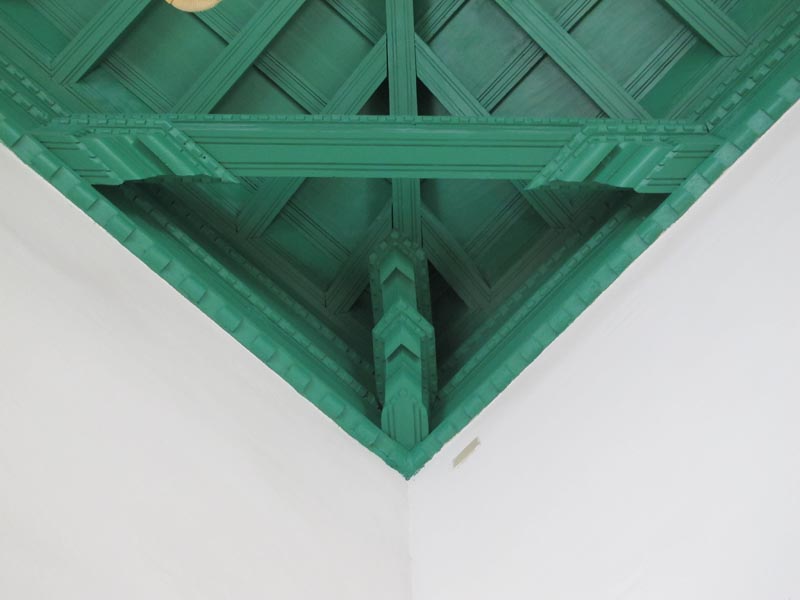

Figures 8 and 9 The current Museo de la Cerámica in Havana in what was a house of an eighteenth-century merchant. The products were sold on the ground floor and the family quarters were located on the first floor. The image of the staircase shows the division of the house with the wooden work. The second image showcases the sophisticated woodwork found in the roofs of residential and commercial buildings erected in Havana in the eighteenth century. Photographs by author.

Figure 10 Interior of the House of Diego de Velázquez in Santiago de Cuba. This building is the oldest structure in the city, fully transformed in the early twentieth-century with a restoration project which saved the building from demolition and re-created domestic interiors. Photograph by author.

Figure 11 Vista of the Castillo del Morro in Santiago de Cuba and the Caribbean Sea. Photograph by author.

Figure 12 Interior of the Basilica of Nuestra Señora de la Caridad del Cobre, in the town of El Cobre in the vicinity of Santiago de Cuba. Photograph by author.

1 The 2018 Edilia and François-Auguste de Montêquin Senior Scholar Fellowship awarded by the Society of Architectural Historians has funded research in Havana and Santiago de Cuba. In addition, a generous research grant awarded by the British Academy/Leverhulme Trust 2017-19 has allowed me to fund research travel to Lisbon and Old Goa and to undertake fieldwork in other locales and buildings sites in Goa, India. I was able to undertake extensive fieldwork in Cuba (and in the Iberian Peninsula and India) having been generously granted a one-semester research leave (from January 2019) by the College of Arts-School of History and Heritage at the University of Lincoln, UK.

2 Damião de Góis, Urbis Olisiponis Descriptio, Évora, André de Burgos, 1554, p.3. A translation into English can be found in J.S. Ruth, Lisbon in the Renaissance. Damião de Góis. A New Translation of the Urbis Olisiponis Descriptio (New York, 1996).

3 See for example, Catarina Madeira Santos, Goa E a Chave de Toda a India: Perfil Politico Da Capital Do Estado Da India, 1505-1570, (Lisbon, 1999).

4 The manuscript is entitled: Llave del Nuevo mundo, antemural de las Indias Occidentales. La Habana descripta: Noticias de su fundación aumentos y estados has been published in print on several occasions since 1830, and is now also reproduced in digital form.

5 This article is part of a Special Issue I have co-edited with Dr Marjorie Trusted entiled ‘Visual and Spatial Hibridity in the Early Modern Iberian World’ forthcoming with Renaissance Studies.

6 I would also like to extend my thanks in the Oficina to Dr Michael González (Director of Heritage), Dr Grisell Terrón (Director of Collections) and Inés María López (International Office) for their warm welcome, support and friendship. I enjoyed and learned much from the conversations with peer architectural historians, particularly Dr Alicia García Santana (Cuban Academy of History) and Dr Maria Victoria Zardoya (Architecture, Universidad Technológica de la Havana - José Antonio Echevarría). In addition, my thanks go to Alexis, Natasha, Ana Lourdes, Marisa, Maite, Alaina (and many more) also at the Oficina, who made my work both possible and enjoyable. I am also grateful for the friendly support of the staff at the Archivo Nacional de Cuba. In Santiago de Cuba I must thank colleagues at the Oficina del Conservador.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top