-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Rediscovering the Bauhaus at 100

Bauhaus Centennial in Weimar, Dessau, and Berlin

October 10-14, 2019

This October, Dr. Barry Bergdoll, professor of art history at Columbia University and former Curator of Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and Dr. Dietrich Neumann, professor of art and architecture and the Director of Urban Studies at Brown University, led SAH participants on a study tour celebrating the 100-year anniversary of the Bauhaus. The tour traced the development of Bauhaus art and design from its 1919 founding in Weimar through the iconic Dessau years to its 1933 demise in Berlin at the hands of the National Socialists. Exploration of important Bauhaus sites in conjunction with special centennial-inspired museum exhibitions in Weimar, Dessau, and Berlin made it clear that the Bauhaus was, in reality, far from a canonical monolith. Rather, the school was composed of multiple and sometimes competing ideas, ideologies, and experimentations from a diverse group of individuals. Understanding that the Bauhaus was more than “a kind of shorthand for an international modern style unmoored from any particular moment”1 makes it possible to recognize it instead as a deeply human endeavor. In the interlude between the devastation of World War I and the tragedy of World War II, the Bauhaus sought to use experimentation in art and design as a way to articulate uncertainties and harness the technological promise of modernity to enhance the expression of life in all its complexities.

Bauhaus – Weimar

While the iconic Dessau structure is nearly synonymous with the “Bauhaus” architectural style today, the school began its life in a building closer in form to Mackintosh’s Glasgow School of Art than the International Style. Belgian architect Henry van de Velde designed the Grand Ducal School of Art and the Grand Ducal School of Arts and Crafts buildings from 1904 to 1911, which Walter Gropius took over in 1919 to form the Bauhaus. Gropius did apply his own design approach to the renovation of his Weimar office, however. The office plan exhibits an imposed geometric rationality based upon the square as the unit of measurement, utilizes primary color accents, and includes a bare tubular metal and fluorescent lighting fixture that would also be incorporated into the Bauhaus Dessau building.

Taking the opportunity to celebrate the work of Van de Velde and his relationship to many of the underlying themes of the early Bauhaus, the tour group visited the Haus Hohe Pappeln, Van de Velde’s Weimar home. The architect designed the house as a Gesamtkunstwerk and lived here with his family from 1908 to 1916.

Henry van de Velde’s Haus Hohe Pappeln in Weimar.

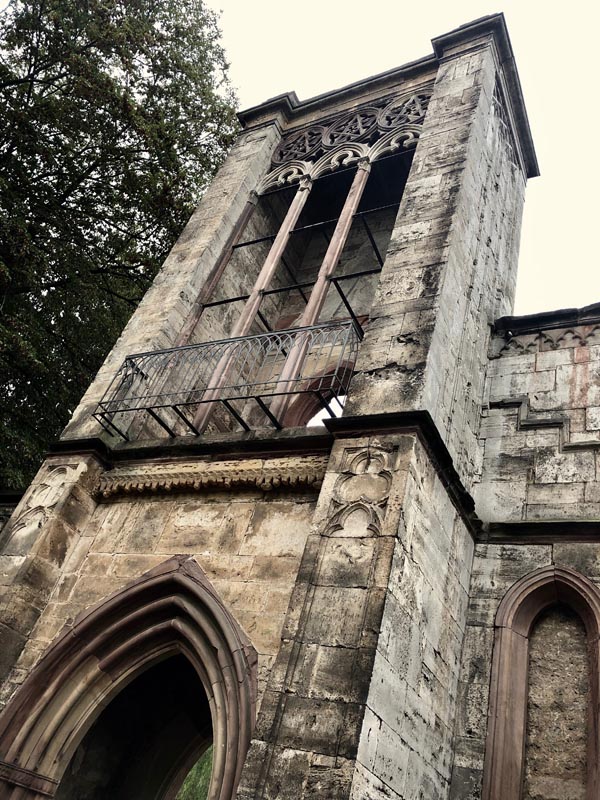

Johannes Itten used this pentagram-ornamented neogothic tower in the Park an der Ilm, designed by Goethe in 1816 for the local Free Masons Guild, as his classroom during the Weimar years of the Bauhaus. Itten emphasized the appreciation of form, color, and material in his introductory course and encouraged his students to participate in meditation practices and vegetarianism. Students of the Bauhaus also held wild parties in this building, which was nearly destroyed in the 1945 bombing of Weimar.

Participants contemplate the Monument to the March Dead, constructed by Gropius in 1922. The design, a concrete expressionist gesture invoking the power and fury of a lightning bolt, commemorates those killed resisting the Kapp Putsch, a right-wing attempt to overthrow the Weimar government. The original monument was destroyed by the Nazis in 1936.

Tour group participants wait to enter the Haus am Horn, built for the Bauhaus’s first exhibition in 1923. It was designed by Georg Muche and constructed with steel and concrete. The house featured furniture by Marcel Breuer and Benita Koch-Otte’s kitchen would later inspire Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky’s Frankfurt kitchen.

Participants were lucky to visit Weimar during the Onion Festival, a tradition dating back to 1653. Food and drink stalls filled with onion tarts, beer, Thuringian sausages, and pretzels, along with craft stalls featuring wreaths and ornaments made from various onion bulbs, filled squares across the city center.

Bauhaus – Dessau

The Bauhaus Dessau was built under the direction of Walter Gropius and his private architectural practice from 1925 to 1926, before the inclusion of architecture within the school’s curriculum. The building consists of three joined units – a vocational school, a workshop wing, and student dormitories. Heavily damaged by Allied bombing in 1945, the building was restored in 1976.

View of the entrance leading into the workshop space on the right and the bridge to the vocational school and Gropius’s office to the left. The bold red color signifies movement and guides circulation through the building.

The concrete frame of the Bauhaus building is visible through the glass curtain wall. The louvered windows open in unison, linked together by a pully and chain system. The mechanism is visible through the glass in the corner of each floor.

Exterior view of the theater and canteen leading into the dormitory tower.

View of the vocational school wing. Marianne Brandt’s light fixtures were used extensively in Bauhaus buildings, and they can be seen here through the windows of the vocational wing. As a woman Brandt had to fight for her place in the metal workshop, though she eventually became director of the department. Brandt also designed the iconic Bauhaus coffee and tea sets.

Gropius and his architectural office designed the Törten housing development for the city of Dessau from 1926 to 1928. The low cost housing units were constructed from prefabricated concrete blocks and beams, which Gropius hoped would allow for a more efficient, organized building process. Ample garden space was included with each unit, providing families with access to fresh air and the ability to grow food. Although most houses in the development have been altered over the years, participants were able to tour a unit that was restored to its original condition.

Constructed from a steel skeleton covered in steel panels, this experimental house was designed by Georg Muche and Richard Paulick in 1926. It is located in the Bauhaus Törten housing development. Despite its austere exterior appearance, the large vertical windows flood each room with light while views out into the surrounding nature enliven the space.

Participants explore the Laubenganghäuer working-class apartments designed by Hannes Meyer and the architecture department of the Bauhaus in 1928. The brick buildings are located next to the Törten housing development.

View down the balcony hallway of the Laubenganghäuer in Dessau.

Store and attached apartment building designed by Gropius in 1928 as part of the Törten housing development in Dessau.

Tour participants examine the Employment Office in Dessau, completed by Gropius in 1929. Clerestory windows and a glass roof brighten the interior (the white trimmed lower windows in the brick exterior were a later modification). The interior was designed to maximize functionality and efficiency – Dessau citizens seeking employment would first divide according to gender and then by occupation, with movable partitions adjusted to control the flow of people through the space.

Participants examine the concrete cantilevered dining room after being treated to lunch at the historic Kornhaus Restaurant. The restaurant was designed in 1929 by Carl Fieger, a draftsman in Gropius’s office.

Gropius and his architectural firm designed the Masters Houses – three semidetached houses for Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Lyonel Feininger, Georg Muche, Oskar Schlemmer, Wassily Kandinsky, and Paul Klee and a detached director’s house – in 1926. The interiors of the fully restored Kandinsky/Klee houses feature an explosion of color, with hues of yellow, lavender, blue, mint, red, peach, black, and white adorning every surface.

Participants explore the Moholy-Nagy/Feininger houses. The Masters Houses were damaged during the 1945 Allied bombing of Dessau and suffered further damage after the war. The Moholy-Nagy house was reconstructed in 2014 by the Berlin firm Bruno Fioretti Marquez as a simplified form symbolizing the destroyed structure – “a blurry memorial of what was irretrievably lost,” according to Dr. Neumann.

Participants listen to the tour guide explain the significance of the Trinkhalle Kiosk adjacent to the Masters Houses in Dessau. The kiosk was designed by Mies van der Rohe in 1932. Punched into the garden wall encasing Gropius’s director’s house, it is the only Mies design in Dessau.

The fourth day of the tour began with a rowboat excursion through the Wörlitz Landscape Garden. The picturesque garden, created by the Duke of Anhalt-Dessau in the eighteenth century, was one of the earliest landscape gardens in continental Europe. It drew much of its inspiration from Stourhead in England, and significantly, was open to the public from its inception.

Bauhaus – Berlin

At the Berlinische Galerie exhibition “Original Bauhaus,” a tour participant has fun recreating the iconic photograph of a masked Bauhaus woman posing in a Breuer chair.

Participants ended the tour with a traditional German dinner at Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s restored Lemke House. Designed in 1932, the back of the small L-shaped house opens up onto a beautifully curated garden. Used by the East German secret police during the Soviet era, the house underwent extensive restoration in 2000.

Before saying goodbye on the final morning of the tour, participants enjoyed breakfast at the rooftop restaurant of the Reichstag. The group took in views of the city from Norman Foster’s 1999 dome addition.

Interior of the Reichstag dome.

Sources

“Bauhaus 100” SAH study tour guide provided by Dietrich Neumann

“Bauhaus Buildings in Dessau,” Bauhaus Dessau Museum, https://www.bauhaus-dessau.de/en/architecture/bauhaus-buildings-in-dessau.html.

Barry Bergdoll, “What was the Bauhaus?” The New York Times, April 30, 2019.

Barry Bergdoll and Leah Dickerman, Bauhaus: Workshops for Modernity 1919-1933 (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2009).

Wita Noack, Mies van der Rohe Schlicht und Ergreifend Landhaus Lemke (Berlin: Form + Zweck, 2017).

Elizabeth Otto and Patrick Rössler, Bauhaus Women: A Global Perspective (London: Herbert Press, 2019).

Wolfgang Thöner, Andreas Butter, Wolfgang Savelsberg, and Ingo Pfeifer, Architectural Guide: Dessau/Wörlitz (Berlin: DOM Publishers, 2016).

Nina Wiedemeyer, ed., Original Bauhaus (Munich: Prestel, 2019).

All photos by Jennifer Tate

Jennifer is a PhD Candidate in Architectural History at the University of Texas in Austin. Her dissertation, Good Americans in Good American Houses: The Politics of Identity and Modern Housing Design in the New Deal Era, examines the intersection between American modern housing and politics, government, and society during the New Deal.

1 Barry Bergdoll and Leah Dickerman, “Curators’ Preface,” Bauhaus: Workshops for Modernity 1919-1933 (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2009), 12. MoMA’s 2009 Bauhaus exhibition approached its examination of the school in these broad, contextual, multifaceted, and personal terms. See also Barry Bergdoll, “What was the Bauhaus?” The New York Times, April 30, 2019.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top