-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Guatemalan Western Highlands and Lake Atitlán

Landscape of loss. German Guatemalans. Sensational cemetery. Underwater wonderland.

When I laid my head down in my Quetzaltenango hostel I had to laugh. I was lying down in a location I did not know existed just a month prior. This city was not on my itinerary, not even on my radar. I ended up in Quetzaltenango, called “Xela,” by residents, thanks to Lonely Planet and some tourist shuttle agency fliers. My original plan was to visit the Petén Department —Flores and Tikal—during my second month in Guatemala. I opted for a location closer to Antigua after learning how long the bus ride would take. Riding the buses through the mountainous terrain of Guatemala was by far my least favorite part of my time there. This major struggle, full of twists and turns which made me nauseated, re-directed my path to discover places I had never heard of previously.

Google Maps snapshot of Guatemalan sites visited in August and September.

I spent approximately two weeks in Xela, and two weeks in San Pedro La Laguna at Lake Atitlán. The Quetzaltenango and Sololá municipal departments, in which Xela and San Pedro are located, make up part of the Western Highlands region of Guatemala. While numerous and diverse Maya people live in this region, the three ethnic groups I came into contact with the most were the K’iche’, Tz’utujil, and Ladino populations. This ethnic information is important historically and geographically, as the culture and built environment of the Western Highlands is inscribed on the landscape, and very much related to the various ethnic communities that reside in the region.

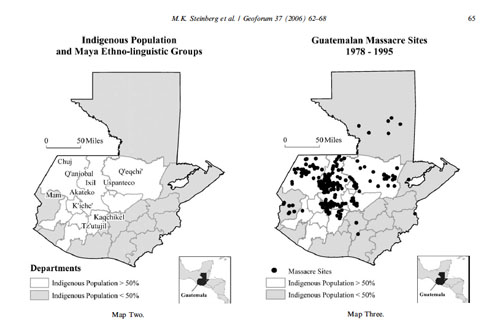

The stories the landscape tells – they are powerful and disconcerting. As geographers Michael K. Steinberg and Matthew J. Taylor note:

Guatemala conjures up both exotic and disturbing images: past and present Maya cultures, Maya ruins, volcanoes and lakes, military dictatorships, and grave human rights violations. Researchers and travelers alike are drawn to Guatemala's beauty and diversity. Yet Guatemala confounds and often repels those who seek to delve deeper into what the landscape means and what it is telling us [emphasis added].[1]

Steinberg and Taylor identified and recorded landmarks and memorials referencing the Guatemalan Civil War in the Western Highlands. They discovered that three main bodies sought to commemorate the war in the “postconfict landscape” – the Catholic Church, the military, and the government. The siting, location, and subject matter of the memorials illustrated that the wounds of the war were still very the fresh and open. Additionally, these memorials were often ephemeral and understated, easily overlooked. The majority of the massacres during the civil war took place in the ethnically diverse Mayan Western Highlands. As cultural anthropologist Benjamin Michael Willett noted in his dissertation “Ethnic Tourism and Indigenous Activism: Power and Social Change in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala,”

The period of la violencia was tragic and the effects that it has had on the Indian communities are devastating – ranging from the total destruction of some four hundred villages and municipal centers to periodic sweeps, repression, and violent killings of tens of thousands of Mayas.[2]

Evidence of these atrocities in the landscape, however, is not readily apparent. Steinberg led a collaborative GIS mapping effort to bring light to this invisible landscape, and the visuals are astounding.

Maps comparing the location of indigenous Maya populations with massacre sites during the Guatemalan Civil War. Source: M. K. Steinberg et al., “Mapping Massacres: GIS and State Terror in Guatemala,” Geoforum 37 (2006): 62-68.

Quetzalteco Exceptionalism

Lonely Planet’s description of Quetzaltenango is not the most flattering piece of prose I have ever read (especially in comparison to the overview of Antigua), but it was this sentence that captured my imagination and left me intrigued:

The Guatemalan “layering” effect is at work in the city center – once the Spanish moved out, the Germans moved in and their architecture gives the zone a somber, even Gothic, feel.[3]

Somber, Gothic, German architecture in Guatemala? I spent a month in extravagant Spanish Baroque Antigua, and I needed to see how this side of architectural expression came to life in the Xela.

Quetzaltenango is the Nahuatl (Aztec) name for the town, meaning “place of the Quetzal bird.” The conquistador Pedro de Alvarado called the city Quetzaltenango after conquering the city for Spain. The Nahuatl were some of his allies in conquest. The town was previously known by indigenous Maya Mam and K’iche’ populations as Xelajú Noj, or “Under the Ten Mountains.” Today the city residents and most Guatemaltecos call it Xela – an act of resistance. The indigenous presence and political power in Xela is stronger than in Guatemala City or Antigua because there is a sizable and influential urban K’iche’ Maya population. As historian Greg Grandin notes:

K’iche’ elites helped to bring the railroad to Quetzaltenango, built public buildings and monuments, established patriotic beauty contests, and gave nationalists speeches. By hitching national fulfillment to cultural renewal, K’iche’s justified their position of community authority to the local and national ladino state. Conversely, by linking ethnic improvement to the advancement of the nation, they legitimized to other Mayans their continued political power. [4]

On my first Sunday in Xela I walked to the Parque Centro América and stumbled across public speeches given by young ladies running for Pequeña Flor de Xela. They averaged around 10 years old, and they were captivating! The content of their speeches and their stage presence was impeccable. They covered topics like the importance of Mayan history and the need to keep the indigenous culture alive. Historian Betsy Ogburn Konefal states in her article “Defending the Pueblo: Indigenous Identity and Struggles for Social Justice in Guatemala, 1970 to 1980” that this tradition of “consciousness-raising” started in the 1970s with young reina contestants, and that they used their time on stage with a public audience to “urge spectators to embrace indigenous identity and take pride in la raza.” [5]

La Municipalidad in Parque Centro América.

The Xela and Guatemala flags were strewn all over the park before the week was out in anticipation of Guatemalan independence activities on September 15. Flags on the Municipalidad, on the Corinthian columns in the park, and on the Casa de la Cultura. The architectural eclecticism of the Xela Parque Centro is noteworthy. It felt nothing like the other cities I had visited in Latin America.

Catedral Metropolitana de Los Altos (Catedral del Espiritu Santo) in Xela. Original sixteenth century façade sits in front of newer, more muted and stark late nineteenth/early twentieth century edifice.

Catedral Metropolitana de Los Altos.

The cultural layers of Xela are fascinating, but fly below the radar for most tourists seeking to learn about Guatemala’s architectural heritage. This might change if ground is gained with the “Route of the Agroindustry and the Architecture Victoriana” that is on the tentative UNESCO World Heritage List for Guatemala. The route, submitted to UNESCO by the Guatemalan Ministry of Culture and Sports, is “constituted by a series of rail stations, buildings of offices, hotels and built residences between the last three decades of the XIX century and the first half of the XX century, to support the development of the export agroindustry that was implemented during that time in Guatemala.”[6] Xela, in addition to its Maya and Spanish roots, had a strong late nineteenth and twentieth century German presence. The Germans came in the late nineteenth century to participate in the coffee industry and contributed significantly to the architectural heritage of Xela. If the idea of what represents “authentic” Guatemalan culture expands, then Xela would place higher on the tourist map. Xela has an urban K’iche’ population, Spanish and German eclecticism, agroindustry and trade, and even more, one of the most strikingly beautiful cemeteries I have ever seen.

Cementerio General

The general cemetery in Xela took my breath away. I lived in New Orleans for three years, and visited and documented some of our most spectacular cemeteries there. Xela had something that the New Orleans cemeteries did not have – vivacity in color. This fact alone brought liveliness to the city of the dead. I went to the cementerio general on a Sunday, and the necropolis was full of life. It was how I imagined Mount Auburn in Boston at the height of the Victorian era – complete with people who passed time in the cemetery for both recreational and commemorative purposes. Xela’s general cemetery was not only a place of quiet respite, but also a place of action. Families are the primary caretakers of the plots. Young and old, men and women wielded axes and machetes to chop the undergrowth, procured water from the countless fountains to wash the memorials, and planted fresh flowers in and around the plots.

A German plot in the general cemetery.

There is not much written about the cementerio general in Xela, which is a shame because it is a wondrous place. It is also a testament to the deep social stratification of the city, from grand shrines of city elites to a mass grave, as well as the ethnic diversity – I came across two different German plots. There is every kind of revival shrine in the cemetery – Greek, Egyptian, Gothic – and some fiercely modern designs that speak to changing tastes over the past century.

View in the general cemetery.

Troubled Water: Lake Atitlán

My time at Lake Atitlán was focused on appreciating and attempting to understand the natural landscape. Lake Atitlán is a caldera lake that was formed 84 thousand years ago. I spent most of my time at the lake in the town of San Pedro La Laguna. There was not much public information regarding the history of the lake. I visited the tiny Museo Tzu’nun Ya’ which had rare historic images of San Pedro La Laguna before the invasion of concrete block structures. The museum also had beautiful interior murals, and a whole room dedicated to the geophysical properties of the lake. Since the majority of the display was in Spanish and the Tz’utujil language, it was difficult to grasp the history of geology displayed in the museum.

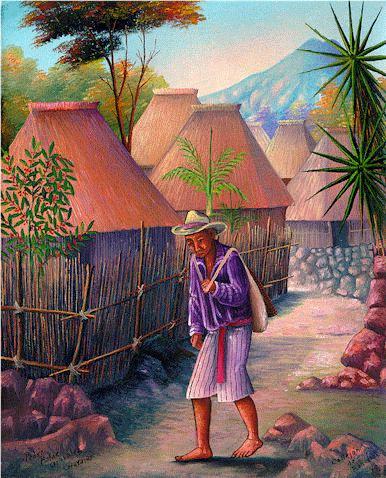

“Callejon de ranchos (Path with thatched houses),” Pedro Rafael Gonzalez Chavajay, 1999. This oil painting by Tz’utujil Maya artist depicts the traditional thatched houses with steeply pitched roof of the San Pedro La Laguna.

View of contemporary San Pedro La Laguna from main cathedral.

One of the most recent and fascinating finds at Lake Atitlán is the submerged Mayan city Samabaj, the “Mayan Atlantis.” Samabaj was a sacred pilgrimage site located on an island in the lake, and was lost when the lake waters rose for reasons still unknown to archaeologists. This site, discovered in 1996 by local diver Roberto Samayoa, was submerged around 250 AD. Lead site archaeologist Sonia Medrano reported that her team found six ceremonial monuments and four altars as well as houses for about 150 people in the ruins of the underwater city.[7]

“La Atlántida Maya,” National Geographic Channel

This discovery is related to another phenomenon that is currently affecting the lake and the communities around it. The city of Samabaj is a reminder that Lake Atitlán is not a static entity – it grows and wanes, has cycles, and changes as the climate and the earth’s crust changes. The lake has risen dramatically in the last decade, submerging lakeside buildings constructed to take advantage of the beautiful views. Author Joyce Maynard writes about this problem in her New York Times article “Paradise Lost.” Maynard mentions the wisdom of a shaman candle seller, who imparted ancient knowledge to explain the changes in the lake: “To the Mayan people, everything is about cycles.” Maynard continues this thought by proclaiming, “Rain comes down. Plants grow up. The lake rises. The lake falls. The lake rises again.”[8] Lake Atitlán is also on the World Heritage Tentative list for UNESCO, and was submitted Ministry of Culture and Sports in 2002, the same year as the “Agroindustry Route.”[9]

Submerged structure in Lake Atitlán.

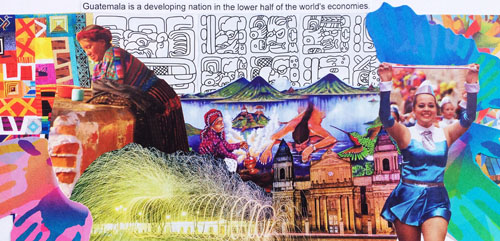

I spent time at Lake Atitlán developing a collage series utilizing magazines collected in Guatemala. The series had a number of different themes, from self-reflection, to active visualization of goals, to organizing random thoughts on architecture and design, to highlighting the mystical powers of women. My final collage for Guatemala is central to my thoughts about the trip. In that collage I reconsidered the “dangerous and poor” Guatemalan narrative projected by various tourist and travel agencies, and contrasted that with the images of Guatemala that left a strong impression on me. The messages that the world circulates about the country do not do it justice. Es un país pequeño con un corazón grande, hermoso.

“Dear Guatemala, Thank you for everything.”

H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship Google Map

Recommended Reading:

Wallace W. Atwood, “Lake Atitlán,” Geological Society of America Bulletin 44 no. 3 (1933): 661-668

Max Paul Friedman, “Private Memory, Public Records, and Contested Terrain: Weighing Oral Testimony in the Deportation of Germans from Latin America during World War II,” Oral History Review 27 no. 1 (Winter/Spring 2000): 1-15

Greg Grandin, “Everyday Forms of State Decomposition: Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, 1954,” Bulletin of Latin American Research 19 no. 3 (July 2000): 303-320

Leah Alexandra Huff, “Sacred Sustenance: Maize, Storytelling, and a Maya Sense of Place,” Journal of Latin American Geography 5 no. 1 (2006): 79-96

Marga Jann and Stephen Platt, “Philanthropic Architecture: Nongovernmental Development Projects in Latin America,” Journal of Architectural Education 62 no. 4 (2009): 82-91

Betsy Ogburn Konefal, “Defending the Pueblo: Indigenous Identity and Struggles for Social Justice in Guatemala, 1970 to 1980,” Social Justice 30 no. 3, The Intersection of Ideologies of Violence (2003): 32-47

W. George Lovell, “The Archive That Never Was: State Terror and Historical Memory in Guatemala,” Geographical Review 103 no. 2 (April 2013): 199-209

Sidney D. Markman, “The Plaza Mayor of Guatemala City,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 25 no. 3 (October 1966): 181-196

Mario Roberto Morales, “Scenes of Lake Atitlán,” Literary Review 41 no.1 (Fall 1997): 5-19

Sandra L. Orellana, The Tz’utujil Mayas: Continuity and Change 1250-1630 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1984)

Elisabet Dueholm Rasch, “Representing Mayas: Indigenous Authorities and Citizenship Demands in Guatemala,” Social Analysis 55 no. 3 (Winter 2011): 54-73

Blake D. Ratner and Alberto Rivera Gutierrez, “Reasserting Community: The Social Challenge of Wastewater Management in Panajachel, Guatemala,” Human Organization 63 no. 1 (Spring 2004): 47-56

Catherine Rendón, “Temples of Tribute and Illusion,” Américas 54 no. 4 (July/August 2002): 16-23

B. G. Smith and D. Ley, “Sustainable Tourism and Clean Water Project for Two Guatemalan Communities: A Case Study,” Desalination 248 (2009): 225-232

Jeffrey S. Smith, “The Highlands of Contemporary Guatemala,” Focus On Geography 49 no. 1 (Summer 2006): 16-26

Michael K. Steinberg, Carrie Height, Rosemary Mosher, and Mathew Bampton, “Mapping Massacres: GIS and State Terror in Guatemala,” Geoforum 37 (2006): 62-68

Michael K. Steinberg and Matthew J. Taylor, “Public Memory and Political Power in Guatemala's Postconflict Landscape,” Geographical Review 93 no. 4 (October 2003): 449-468

Matthew Tegelberg, “Framing Maya Culture: Tourism, Representation and the Case of Quetzaltenango,” Tourist Studies 13 no. 1 (2013): 81-98

James W. Vallance, Lee Siebert, William I. Rose Jr., Jorge Raul Girón,

and Norman G. Banks, “Edifice Collapse and Related Hazards in Guatemala,”

Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 66 (1995): 337-355

Daniel Winterbottom, “Garbage to Garden: Developing a Safe, Nurturing and Therapeutic Environment for the Children of the Garbage Pickers Utilizing an Academic Design/Build Service Learning Model,” Children, Youth and

Environments 18 no. 1 Children and Disasters (2008): 435-455

_______________________________

[1] Michael K. Steinberg and Matthew J. Taylor, “Public Memory and Political Power in Guatemala's Postconflict Landscape,” Geographical Review 93 no. 4 (October 2003): 450.

[2] Benjamin Michael Willett, “Ethnic Tourism and Indigenous Activism: Power and Social Change in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala,” (PhD diss., University of Iowa, 2007), 13.

[3] Lonely Planet, “Introducing Quetzaltenango”

[4] Greg Grandin, “Can the Subaltern Be Seen? Photography and the Affects of Nationalism,” Hispanic American Historical Review 84 no. 1 (February 2004): 91

[5] Betsy Ogburn Konefal, “Defending the Pueblo: Indigenous Identity and Struggles for Social Justice in Guatemala, 1970 to 1980,” Social Justice 30 no. 3, The Intersection of Ideologies of Violence (2003): 36

[6] UNESCO, “Route of the Agroindustry and the Architecture Victoriana”

[7] Sarah Grainger, “Divers probe Mayan ruins submerged in Guatemala lake,” Reuters October 30, 2009

[8] Joyce Maynard, “Paradise Lost,” New York Times May 20, 2012

[9] UNESCO, “Protected area of Lake Atitlán: multiple use,”

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top