-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Overcrowded Sites and Unexpected Voids: The Extremes of Tourism in Iceland and the Faroe Islands

All photographs and videos are by the author, unless otherwise noted.

With travels this month in the Vesturland, the southern portion of the Ring Road known as the Sudhurland, and a trip to Vestmannaeyjar, I logged nearly 2,000 miles in Iceland in August. Although my itinerary included only the bottom half of the nation, the distance I traversed was twice the length of the Ring Road [Route 1]. Advertised as a tourist route that takes a little over a week, my travels thus far have highlighted the fact that the best parts of exploring Iceland are the detours (Figures 1 and 2).

Figures 1 and 2. The Gluggafoss waterfall and timber church found in the neighboring village are located just north of the Ring Road, near the Þórsmörk nature preserve.

It is difficult not to stop every few miles to take in the landscape or see what hidden gems may be found down a side road. The possibilities of this type of exploration around the island, however, are recent: the portion of the Ring Road connecting the capital and Höfn, a town east of the nation’s largest glacier, was only completed in 1974. Visitors to Hofskirkja (b.1884; reconstructed 1954), one of the last turf churches constructed on the island and surrounded by some of the only preserved turf graves in the nation, once had to travel around three-quarters of the nation’s perimeter to reach the site (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The Hofskirkja still serves as a parish church and it is one of the structures maintained by the National Museum of Iceland.

Through much of the 1980s, the road between Reykjavík and the international airport (KEF) was the only thoroughfare paved with asphalt. Consequently, Vik, the southernmost town on the island, was largely inaccessible. The dramatic cliffs filled with puffin nests, black sand beaches, and basalt formations in the shape of arches and columns that inspired stories of fanciful elfin churches (Figures 4-7) were desolate except for local villagers and intrepid travelers with vehicles equipped to traverse the varied landscape (Figure 8).

Figures 4 and 5. Visitors are permitted along the cliff’s marked paths and portions of the beaches but other areas are restricted to protect the nesting puffin population.

Figure 6 and 7. From the beaches of the Vik region, visitors can see the Mýrdalsjökull glacier as well as several architectonic natural wonders: the Dyrhólaey arch, the Arnardrangur pier, the Reynisdrangar columns, and basalt caves of Reynishverfi beach.

Figure 8. A small sampling of the ever-growing photographic collection of monster cars and trucks around Iceland.

Today, however, is a different story. The sites surrounding Vik comprise some of the most popular destinations on the island, outside of the capital region. During recent visits, Vik’s small gas and service station was overwhelmed with vehicles and the paths along the beaches and cliffs were packed with bird watchers and selfie-stick armed explorers. Alarmingly, there were also multiple tourists walking along the narrow, gravel shoulders of the Ring Road, casually seeking secret routes to beaches and mountain walks. Many seemed like they were trying to recreate the scenes of Justin Beiber’s I’ll Show You that was filmed in south Iceland. Rather than celebrating the region's wonders, the video seems to promote an irresponsible attitude towards foreign sites and disrespect for precious landscapes. In the three and a half minutes of the video, he runs through the slippery waterfalls paths of Seljalandsfoss and Skógafoss, perches precariously close to cliff edges, swims in the restricted glacial lagoon, and skateboards across the ruins of a U.S. Navy Douglas Super DC-3 plane crash along Sólheimasandur beach. Aside from the recent music video, widely shared amateur photographs of the hollow fuselage made the plane crash site a frequent stop for curious travelers. However, some visitors have all but destroyed the site: in March 2016 the owners of the 3km path leading to the site restricted car access because of noticeable beach erosion and in June access to the site was entirely barred when someone vandalized the plane. On August 29, matters intensified when a tourist was charged ISK 100,000 ($850) after entering the area with a rental car and in the coming months more legal action may result from the event.

To further explore some of the issues noted above, this month’s blog entry is comprised of a few short ‘chapters’ that highlight some of the successes and struggles related to tourist navigation as well as the discrepancy, especially in Iceland, between certain sites that are receiving too many visitors and sites that are strategically positioning themselves as new travel destinations.

The Bureaucracy of Travel

Throughout my travels, workers in regional tourist offices and the Icelandic Tourist Board have been very generous with their time. In early August, I met with the Vice-President of the European Travel Commission in Iceland, Ólöf Ýrr Atladóttir. As we talked in her office that overlooked the old harbor of Reykjavík, the former ranger in the Highlands explained her unique insight regarding Iceland’s shifting attitude towards tourism and she offered some quite thought-provoking comments on Iceland’s relationship with transient travelers. In the 1990s and in the first decade of the 2000s, national park rangers were responsible for the general maintenance of sites and restricting access to certain areas of the island, especially the Highlands. Today, however, there is a developing culture of education: instead of entirely baring entry to select sites, the rangers hope that through open access visitors will be empowered to contribute to conservation and preservation efforts. Many of Iceland’s new educational programs and way finding strategies were modeled on the National Park Service of United States, celebrating its centenary this year, and like the NPS, rangers in Iceland now find themselves in more specialized roles within both parks and school initiatives. Although much of Iceland is now open to visitor exploration through entrepreneurial tour companies such as ‘Extreme Iceland’ and rental companies that offer a range of 4x4 vehicles to traverse the region’s F-Roads, this also means that less experienced travelers are taking more adventuresome treks.1 Fortunately for the rangers and emergency responders, the majority of visitors come to the island in the summer when most of the nation’s roads are open and weather conditions are at their best. Nonetheless, there are steady increases in traveler numbers in the darker months due to advertisements for Northern Lights excursions and Icelandic layover packages for the winter holidays. Around the winter solstice, there are only four hours of daylight but according to rising visitor numbers this condition seems to entice, rather than deter, visitors who want a chance to see atmospheric phenomena or experience events such as the illumination of Yoko Ono’s Imagine Peace installation. This rise in year-round tourism necessitates increased safety measures on the island and recently the 112 emergency response service developed a geo-locating, mobile app that explorers can use to track their position on the island and, in worst case scenarios, assist emergency responders in rescue missions (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Signs such as this one occupy Iceland’s most popular tourist sites.

Beyond health and safety, the Tourist Board is facing critical questions about infrastructure to support the influx of visitors. According to Atladóttir, it is generally accepted that everyone who lives on the island is a host. Nonetheless, this symbiotic relationship is overtaxed, particularly in Reykjavík, since locals are quickly realizing the extent to which their public spaces and services must be shared with visitors. Consequently, officials from the Icelandic Tourist Board are promoting campaigns for exploration beyond the capital region and encourage ‘slow tourism’, a concept counter to the current touristic ‘sprint’ of Icelandic layover packages. By encouraging people to stay longer and explore farther afield, the Tourist Board hopes that the strain on certain sites in the capital region and south Iceland will be reduced and that visitors will be dispersed more evenly around the island. For example, less than a quarter of visitors to the island make their way to the West Fjords but improvements in crossroads for cars, buses, and bikes, as well as investments in small town initiatives may change this. It is estimated that over 90% of visitors to the island visit the Blue Lagoon so the Tourist Board also plans to extend the promotion of water-based tourism by leveraging existing resources such as hot pots, community geothermal pools, and boating opportunities (Figure 10).

Figure 10. The Jökulsárlón Glacier Lagoon is home to a number of boat slips for exploring the icy waters.

Although travel magazines are still promoting the possibilities of the nature pass, the Tourist Board sees little potential for the success of the pass due to the complications of forging partnerships between public and private land interests. Nonetheless, tourism will be a popular topic for the upcoming Icelandic parliamentary election. As explored in previous posts, the visitor numbers to Iceland are escalating much faster than necessary conservation or infrastructure projects. There is additional pressure on the nation’s road network due to those traversing the Golden Circle and Ring Road as well as the increased number of trucks bringing food and supplies from Reykjavík’s shipping terminals to other parts of the nation. More frequent bus journeys and increased numbers of rental cars on the road also mean that the Tourist Board is monitoring issues that are infrequently discussed in glossy travel magazines: waste and the lack of public restrooms. Iceland’s Academy of the Arts and the Tourist Board are keen to address these topics and it is clear that local architects are also responding to the challenges of building a sustainable network for tourism. For example, the Visitor Center of Snæfellsstofa in Vatnajökull National Park, designed by the Icelandic firm ARKÍS, is the first new building in nation to received BREEM certification. As I plan my travels around the Ring Road in September, I am looking forward to exploring a number of other, new visitor centers currently under construction as well as the adaptive reuse projects that are converting sites in the north and eastern parts of the island into tourist offices and regional museums.

Vestmannaeyjar

While the south of Iceland was inundated with tourists in August, the archipelago of Vestmannaeyjar, also known as the Westman Islands, was eerily quiet during my visit. As the result of thousands of years of volcanic activity, Vestmannaeyjar consists of eleven main islands, four smaller islands known as the Smáeyjar, and more than two dozen other volcanic formations that rise from the rough seas. The newest island, Surtsey, was the result of a subsea volcanic eruption that lasted from 1963 to 1967. As a site where scientists are actively studying ‘a pristine natural laboratory’, the island was inscribed as a natural UNESCO World Site in 2008. Only certified researchers are permitted access to the island and all other visits by land or sea are prohibited, minimizing detrimental impacts from human intervention. As a popular vacation destination for Icelanders, the majority of the islands of Vestmannaeyjar are actually untouched and only one of the islands, Heimaey, is permanently inhabited (Figure 11). Besides providing a remarkable background for hikes around Heimaey’s two volcanoes, a number of the other islands have impossibly tall and rusted chain ladders connected to rough harbors that give locals access to perched summer homes, sheep grazing sites, and annual egg collecting trips.

Figure 11. The narrow harbor entrance to Heimaey and constructed stave church, discussed later in the post.

A ferry terminal in Landeyjahöfn, a manmade harbor just south of the Ring Road and Seljalandsfoss waterfall, was opened in the summer of 2010 and now offers visitors a quick 35-minute ride to the main harbor on Heimaey (Figure 12). Prior to the construction of the new ferry terminal, residents and visitors could only reach Vestmannaeyjar by plane, helicopter, or a nearly four-hour ferry trip from Þorlákshöfn, a port near Reykjavík that is still used during the winter months and in poor weather.

Figure 12. A portion of the Heimay harbor and cliffs of Vestmannaeyjar in the background.

The lack of visitors to Vestmannaeyjar during my visit may have been due to the fact that the main tourists to Vestmannaeyjar are Icelanders and in early August the nation is preparing to return to school and work following the end of the summer holidays. Additionally, the biggest event in the area, the Westman Islands Festival, occurred the week before so the quietude may have been a welcome break for residents. Held in the Herjólfsdalur crater of Heimaey and celebrated annually in early August since 1874, the festival has grown into a four-day event and with nearly 20,000 in attendance it is now Iceland’s largest outdoor festival.

Although the main hotel in town, campsites, and guesthouses were largely booked during my stay, the town was practically empty. Few stores, cafes, or restaurants were open despite the fact that almost every corner of the harbor’s downtown had vibrant window advertisements, fresh paint, and quirky interior decorations that illustrated careful attention to cultivating the individual character of each place. This reminded me a bit of Marfa, Texas, where various restaurant and cafés were open on a rotating schedule, ensuring that each of the town’s culinary entrepreneurs could contribute to the local economy and keep mealtime a bit interesting for the town’s curious, artistic visitors.

Despite the quiet streets and shops, Vestmannaeyjar is actively positioning itself as a tourist destination and unlike typically reactive tourist campaigns that scramble to meet the needs of rising visitor numbers, Vestmannaeyjar is taking steps towards sustainable operations that are hinged on complete energy independence by 2020. By harnessing wave energy conversion and wind power as well as heat from fish processing and waste incineration plants, it could be possible for Heimaey to be free of fossil fuels [with the exception of the island’s ships] by the next decade. To encourage visitors, the Vestmannaeyjar app launched last fall and it orientates visitors to Heimaey through a series of interactive maps that showcase points of interest, restaurants, and sites for swimming and hiking. Designed by the Reykjavík-based company Locatify, the app portrays Heimaey as a hotspot for recreation and exploration. But in mid-August, it was no exaggeration to claim that nesting puffins far outnumbered people in Vestmannaeyjar.

Figure 13. A sign near the harbor advertising a local gallery with wool crafts and handmade sweaters.

The islands are home to the largest colony of Atlantic Puffins in the world and although residents of Vestmannaeyjar once hunted the endearingly awkward birds (Figure 14), the dwindling numbers of puffins inspired residents to actively protect the species. Unlike Reykjavík, visitors to Heimaey’s restaurants will not find puffin on the menu and caricatures of the birds adorn nearly every souvenir, business advertisement, and even the street signs of the town (Figures 15-19).

Figure 14. An installation on the side of the fish processing plant on Heimaey illustrating the nets once used to capture puffins in Vestmannaeyjar.

Figures 15-17. Puffin street art and advertisements in Heimaey.

Figures 18 and 19. The street signs of Heimaey.

Visitors can get a closer view of the islands’ puffins at play by boarding rigid inflatable boats (rib) at the harbor that speed around the crags and caves of the neighboring islands (Figure 20). After seeing the habitat of such a large colony up close, it is possible to see parallels between the deep puffin burrows in the cliffs and some of the earliest structures made by Iceland’s Viking settlers: shelter was created by digging into the soft turf amid lava rocks and these conditions provided protection from the harsh climate as well as a bit of camouflage from invaders (Figure 21).

Figure 20. A partially filled rib speeding past the harbor.

Figure 21. Built in 2006, Herjólfur’s Farmhouse is hypothetical reconstruction based on 9th century the archaeological remnants of a longhouse discovered on the island in the 1970s.

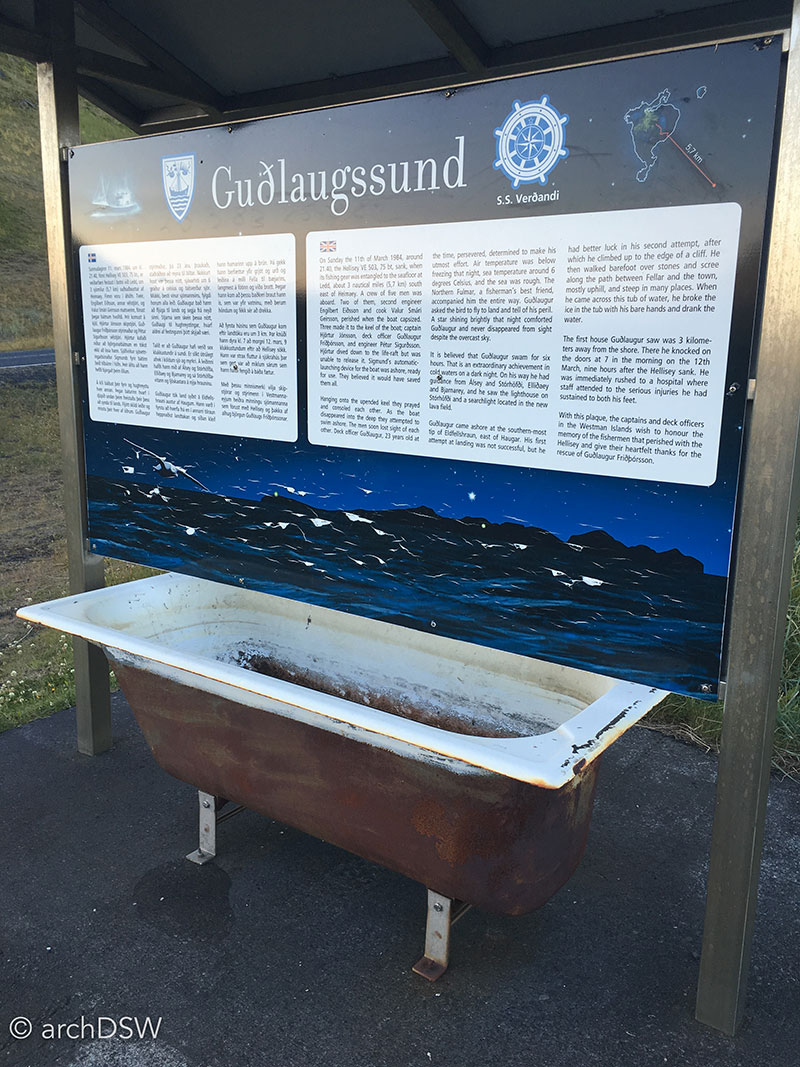

Beyond opportunities for puffin sightings, the rib proved to be the best way to see the islands’ incredible rock formations and examples of ‘elfin’ architecture while local guides showcased their storytelling skills with epic tales of shipwreck survivals. Later excursions around Heimaey demonstrated that many of the stories are memorialized with small installations, such as the Guðlaugssund that marks epic swim, climb, and lava rock walk made in March 1984 by Guðlaugur Friðþórsson, the sole survivor of the S.S. Verðandi (Figure 22).

Figure 22. After swimming in nearly freezing water for six hours, scaling a cliff, and treading across jagged lava rocks barefoot, Friðþórsson cracked the icy film on this abandoned tub in search of fresh drinking water. Nicknamed the human seal, Friðþórsson’s story was retold in The Deep (2012)

Vestmannaeyjar is entirely excluded from A Guide to Icelandic Architecture (2000) but the island contains a range of interesting historical and architectural sites in addition to the well-known wonders of its natural landscape. Although some of the domestic architecture is not to be missed, composed of colorful corrugated iron like much of the Iceland’s capital, and there is a quirky, geodesic convenience store from the 1970s (Figure 23), the key heritage sites on Heimaey can be explored with the Vestmannaeyjar cultural pass: the Sæheimar Aquarium & Natural History Museum, the Sagnheimar, and the Eldheimar. The first site is little more than a two-room conversion of the upper floor a commercial building near the harbor but it serves as a rescue and rehabilitation center for puffins and there are plans to expand the museum in partnership with the Research Center of Vestmannaeyjar. The Sagnheimar Folk Museum occupies the upper floor of the Heimaey library and features exhibits about harbor life and the impact of Mormon missionaries on the island between 1854 and 1914. The museum is also home to a small exhibit about the eruption of Eldfell but this has been superseded by the new and captivating Eldheimar, a museum dedicated to telling the story of the 1973 volcanic eruption that dramatically changed the landscape of Heimaey (Figures 24-26c).

Figure 23. The prefabricated system of the building provided a logical construction system for work on the island and the result is certainly more intriguing than the bog box structure of the new grocery store.

Figure 24. A painting along the harbor marking the eruption of Eldfell.

Figure 25. One of the most dramatic images of the eruption shows lava overtaking the Landskirkja church in downtown Heimaey.

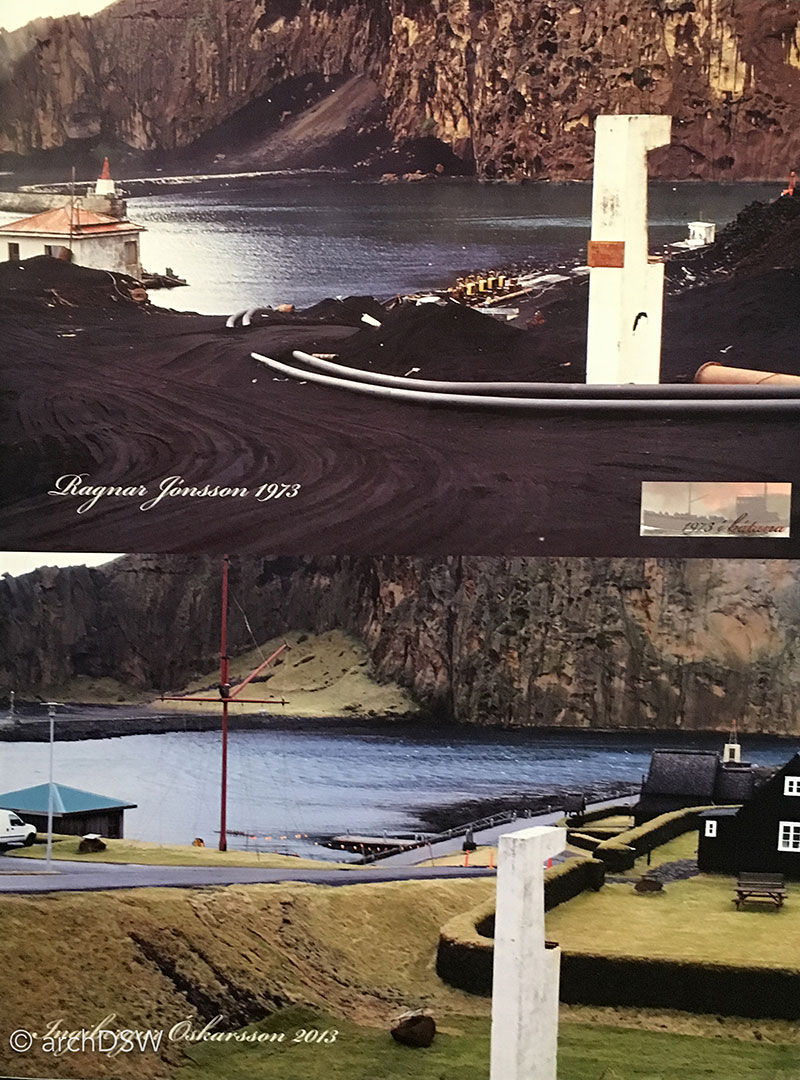

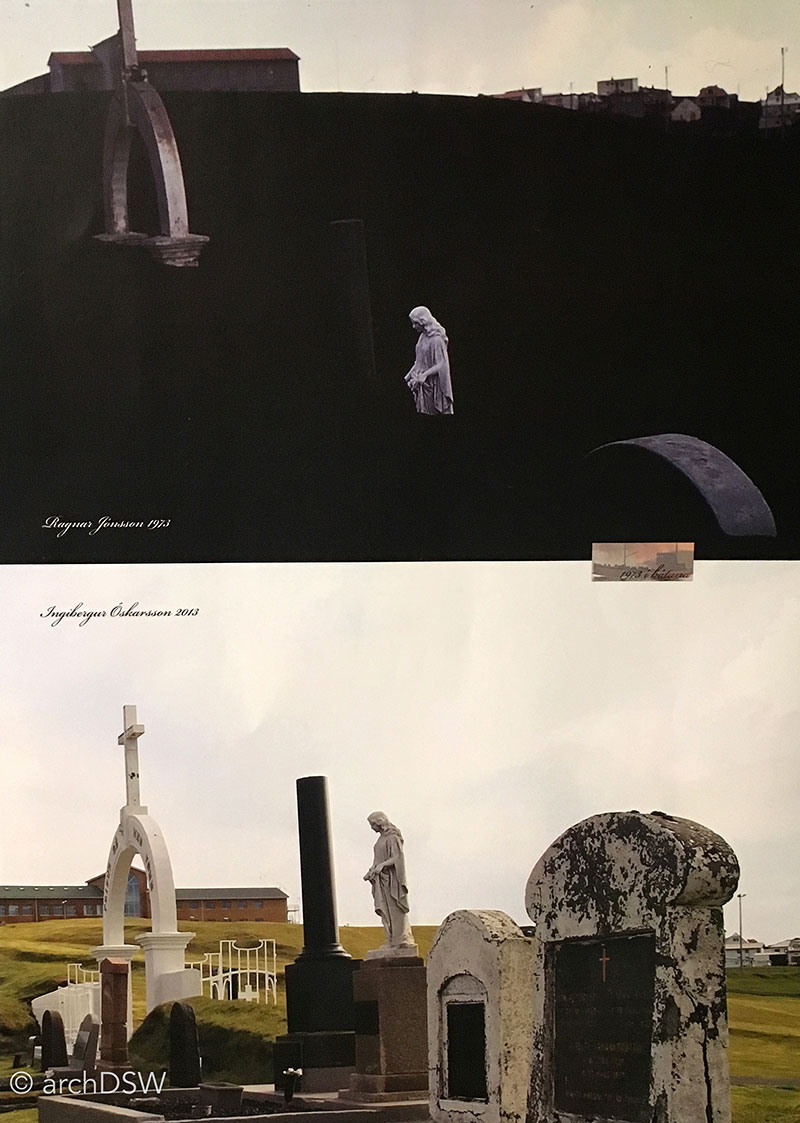

Figures 26a-c. A series of images in the Folk Museum show before and after scenes of the volcanic cleanup on Heimaey.

Eldfell initially erupted in the early morning hours of January 23, 1973, and forced the evacuation of more than 5,000 of Heimaey’s inhabitants. Over the next five months, lava from the volcano continued to flow. More than 400 homes and businesses were destroyed and Heimaey’s lifeline was nearly obliterated when lava poured over the cliffs and threatened to close the already narrow entry to the harbor (Figures 27-30).2

Figure 27. The partially excavated ruins of a home are visible near the entry of the Eldheimar. A BBC documentary, available here, showcases footage of the eruption, evacuation, and cleanup efforts.

Figure 28. In late March 1973 lava flowed towards harbor, destroying water tanks and threatening the fish processing plants and harbor that sustained the majority of Heimaey’s economy.

Figures 29 and 30. Today, igneous rocks form the northern portion of the harbor and the expansion of the island to the northeast due to the lava is clearly visible from hiking paths around Eldfell. A useful map of the island’s volcanic expansion can be found here.

In 2005, Vestmannaeyjar approved the excavations of a number of homes that were still buried by ash. The project was nicknamed of the ‘Pompeii of the North’ and the Eldheimar is literally constructed around the ruins of one residence (Figures 31 and 32). Once a home to a family of four, 10 Gerðisbraut was buried beneath the ash until 2013. Landscape architect Lilja Kristín Ólafsdóttir, architect Margrét Kristín Gunnarsdóttir, designer Axel Hallkell Jóhannesson, and the interaction design group Gagarín decided to use the home as centerpiece of the museum, dramatically lighting the ruins and allowing visitors to circulate around the site (Figures 33 and 34). Through the use of suspended catwalks and live, telephoto cameras, visitors can get closer views of the home and items left behind in the rush to escape the lava. Handheld guides that were designed by the same developers of the Vestmannaeyjar app are used to geo-locate visitors’ positions within the museum and autonomously cue supplementary audio and video content.

Figures 31 and 32. A corten steel screen covers portions of the museum’s glazed curtain wall to reduce glare on the internal, interactive screens.

Figures 33 and 34. Working in concert, the physical and virtual elements of the museum allow visitors to see, touch, hear, and even smell the how the volcano impacted the Vestmannaeyjar.

Although many villagers returned after the eruption, Heimaey’s population has yet to surpass numbers from pre-1973. The eruption of Eldfell was massively destructive but it provided a few opportunities for the island. As a captivating amalgamation of archaeology, geology, and museum interpretation, the Eldheimar won 2015 Honor Award from the Society of Experiential Graphic Design and was the recipient of the 2015 Icelandic Design Award. Additionally, the new rock formations by the harbor provided the foundations for one of the most visible architectural projects on the island: the reconstruction of a stave church (Figure 11). Built between 1998 and 2000 and sponsored by the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NINU-NIKU) in celebration of the millennial anniversary of Iceland’s conversion to Christianity, the church’s features and construction techniques were modeled on elements of the Haltdalen stave church (c.1170 AD) that is now part of the Sverresborg Trøndelag Folkemuseumin in Trondheim (Figures 35-37). To resist weathering and the harsh harbor wind, the nave is protected by a double wooden skin, creating an insulating ambulatory of sorts, and the exterior of the structure was covered in tar (Figures 38 and 39). Therefore, the warm, untreated timber of the interior provides a striking visual contrast to the dark cladding (Figures 40 and 41).

Figures 35-37. Unlike many of the small parish churches around Iceland, the stave church is regularly open to visitors.

Figures 38 and 39. The path between the exterior skin of the church and protected nave is illuminated with small, arched apertures.

Figures 40 and 41. The substantial doors of the church are affixed with reproductions of medieval hardware.

An introduction to the Faroe Islands

Currently, I am in the Faroe Islands and despite some tricky summer storms, I am exploring several of the eighteen islands in the archipelago. In order to make the most of my journeys between Iceland and the Faroe Islands, and to attend the wedding of close friends in England, I flew to Vágar on the Faroe Islands from London, with a brief layover in Copenhagen. Following Jeffersonian advice for my quick visit to the city, I bought a map and guidebook [now available online through the Copenhagen city card app], I walked a portion of the city’s perimeter, and then climbed a steeple to, “view the town and its environs.” (Figure 42)3 Within twenty-one hours, I made frenzied visits to several churches, the National Gallery of Denmark and its ‘street of sculpture’, Daniel Libeskind’s Danish Jewish Museum, and the Tivoli Gardens (Figures 43-49).

Figure 42. The tight stairs spiraling around the spire of the Church of Our Savior in Copenhagen (1690s-1752).

Figures 43-45. The National Gallery of Denmark

Figures 46 and 47. The Danish Jewish Museum, designed by Daniel Libeskind in 2003, occupies the former Royal Boat House.

Figures 48 and 49. The mid-nineteenth century amusement park occupies a central location in Copenhagen and is filled with a range of rides, architectural follies, and picturesque landscapes.

The two-hour flight from Copenhagen to Vágar Aiport (FAE) was quite luxurious compared to the protocol of European or American hopper flights: Atlantic Airways provided generous baggage allowances and the in-flight meal consisted of sushi and Faroese beer. To add to the serendipitous convenience, the Air B&B host for my stay in the small town of Sandavágar on Vágar worked in the airport's Tourist Information office so I had quite the knowledgeable guide at hand.

Figure 50. The brightly colored metal and wood of the Sandavágur Church (1917) stand in contrast to the landscape.

While based in Sandavágur, I had my first introductions to the Faroe Islands (Figure 50). The eighteen islands are connected through an impressive system of ferries, bridges, and tunnels, through both mountains and beneath the sea. Many of these tunnels, however, are one lane. The tunnels privilege one direction and force those opposing to pull into small, carved niches placed every 100 meters to allow oncoming traffic to pass. The experience of traversing these tight, darkened tunnels with water streaming down the rough walls makes one even more appreciative of the spacious views from the roads that snake along cliffs and valleys (Figure 51 and Video 1-2). Driving through the unpredictable landscape, it is also understandable that Google used cameras mounted to sheep to record data for the islands’ Street View.

Figure 51. The entry to a single lane tunnel on Kunoy.

Faroe Islands drive: Gásadalur-Klasvík from Danielle Willkens on Vimeo.

Video 1. Scenes from the Faroe Islands, exploring the islands of Vágar, Streymoy, Eysturoy, and Borðoy. The drive passed through the following towns: Gásadalur, Bøur, Sørvágur, FAE, Sandavágur, Vestmanna, Stykkið, Kollafjørður, Hósvík, Hvalvík, Oyrarbakki, Skipanes, Syðrugøta, Norðragøta, Leirvík, and Klaksvík.

Faroe Islands: Kunoy, Borðoy, and Viðoy from Danielle Willkens on Vimeo.

Video 2. Scenes from the Faroe Islands, exploring the islands of Kunoy, Borðoy, and Viðoy.

The bus and ferry systems around the islands are subsidized by the government, making them affordable ways to travel and, for select islands, the ferries are still the main means of transport for workers, mail, supplies, and even commuting schoolchildren. In Vágar and the northern islands, it is hard not to take note of the incredible infrastructure of the islands, ranging from the transportation systems to power to the conveyance of water (Figure 52). Even the smallest of towns, consisting of less than ten inhabitants, have strong cell phone signals, streetlights, and partially mechanized harbors for fishing and personal transport. Steep, grass-covered volcanic mountains are filled with countless cascades but, somehow, perfectly aligned fences mark the boundaries between farms.

Figure 52. The hydroelectric infrastructure of Vestmanna on Streymoy.

Figure 53. On the central mountain formation in the image it is possible to spot the thin white line of a fence dividing two sheep grazing sites.

Tourist advertisements boast that the Faroe Islands are, “a place undiscovered” and with few other travelers in sight, this phrase seems true (Figures 54-56). I may find different conditions in the capital region, but thus far, it feels like a privilege to explore the quiet vernacular of the Faroe Islands (Video 3).

Figure 54a and b. The covers of the 2015 and 2016 travel guides produced by the Faroe Islands Tourist Office.

Figures 55 and 56. Scenes from the island of Viðoy in the north.

Faroe Islands: Vágar fishing ruins from Danielle Willkens on Vimeo.

Video 3. Drone footage of an abandoned fishing outpost in Vágar along the largest lake in the Faroe Islands, Leitisvatn.

As I write from Klasvík, barely able to see streetlights across the inlet and listening to the 40 mph wind gusts rattle my windows during a ‘common’ summer storm in the North Atlantic, I look forward to my trip to the capital of Tórshavn on the island of Stremoy and investigating the southern islands. Next month’s post will feature maps, photographs, and narratives of my full travels through the Faroes, but I will conclude this month’s posting a few previews of the footage captured so far (Videos 4-6).

Faroe Islands: Hvannasund on Viðoy and Norðdepil on Borðoy from Danielle Willkens on Vimeo.

Video 4. Drone footage of the sister harbor towns of Norðdepil on Borðoy and Hvannasund on Viðoy, showing the dam across the North Atlantic that connects the two towns.

Faroe Islands: Viðareiði on Viðoy from Danielle Willkens on Vimeo.

Video 5. Drone footage of Viðareiði on Viðoy, the northernmost settlement of the Faroe Islands. The shape of the sea cliff traps driftwood and this property is the namesake of both the town and the island: viður is Faroese for ‘timber'.

Faroe Islands: Haralssund on Kunoy from Danielle Willkens on Vimeo.

Video 6. Drone footage of the colorful coastline of Haralssundon Kunoy.

PS: I hope that the Icelandic Meteorological Office’s prediction for the eruption of Kalta does not occur in the near future…

Bibliography

Boyd, Julian P., Charles T. Cullen, John Catanzariti, Barbara B. Oberg, and et al., eds. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 40 vols. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1950-.

Williams, Richard S. Jr., and James G. Moore. "Man against Volcano: The Eruption on Heimaey, Vestmannaeyjar, Iceland." Denver, CO: USGS Information Services, 1976. Reprint, 1986.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top