-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

A Year as the SAH H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellow: Reflections on Travel, Time, and Technology

Even though I am, once again, immersed in university teaching and a few burgeoning research projects, I know that I will be processing the experiences of the SAH Brooks Fellowship for years to come and it is not an understatement to say that the sponsored travels have shaped a new trajectory for my interests and advocacy within the development and preservation of built environment. Undoubtedly, the fellowship changed the way that I understand architectural history: I found that certain sites and architectural figures are so much more interconnected than I could ever imagine. With this in mind, I can envision new ways to teach the requisite architectural history surveys in professional architecture programs that can move beyond chronology and certain geographic biases (eastern vs. western) to pursue a more thematic approach to history that emphasizes parallels across time and place through the lenses of form, building materials, technology, and the exchange of information through travel. Additionally, as an American architectural designer and historian, teaching within an American architecture school, Iceland and the Faroe Islands provided new ways to think about sustainable design, Cuba provided vivid examples of resourcefulness but also the perils of building decay without regular maintenance, and my time in Japan radically changed how I understand fundamental elements of architecture, such as ‘the wall’, and how I read and interpret the work of Frank Lloyd Wright and others who first explored Japan in the early modern era.

A Google Map of key sites, natural features, cities, and towns visited in Iceland between June and September 2016.

A Google Map of key sites and towns visited in the Faroe Islands between late August and early September 2016.

A Google Map of key sites and towns visited in Cuba between October 2016 and January 2017.

A Google Map of key sites and towns visited in Japan between February and May 2017.

Endangered Islands?

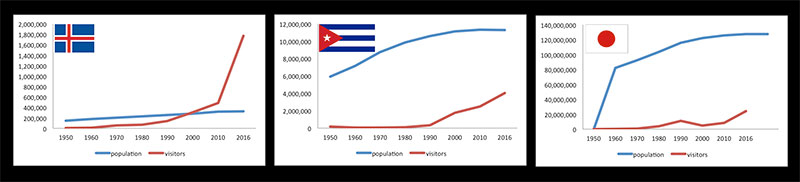

Concentrated on providing early career scholars and practitioners unparalleled opportunities for travel and the priceless gift of time to explore sites thoughtfully, the fellowship allowed me to visit several nations that are undergoing dramatic changes in their built environment, primarily due to surges in seasonal tourism (Figure 1). In Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Cuba, and Japan, I was fortunate to witness several major events: an entire nation’s population gathered in the capital city of Reykjavik to cheer their football team on to several unexpected victories, the death of Fidel Castro and the state-imposed period of mourning in Cuba, and Japan’s preparations to take the Olympic center stage despite a declining population and rising uncertainties from military unrest along the Japan Sea.

Data from national censuses, tourist boards, and the World Bank showing the changes in population and tourism in Iceland, Cuba, and Japan from 1950 to the present.

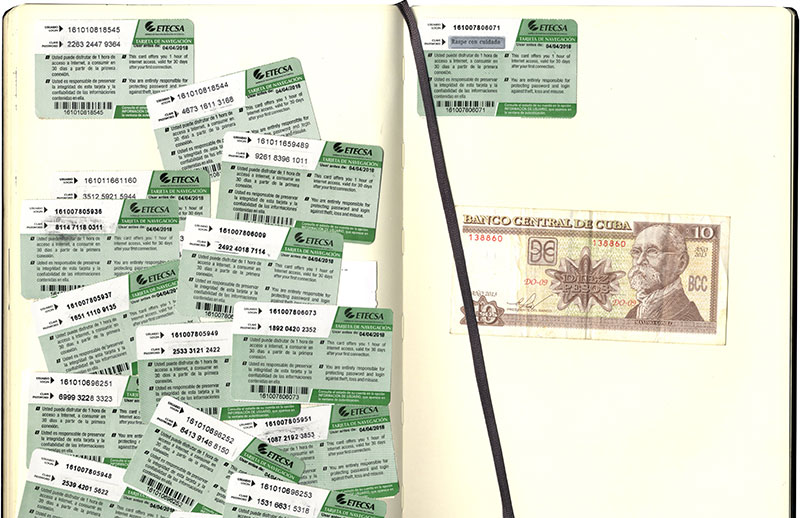

As the SAH’s H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellow, I stayed in seventy-five residences. Thankfully, many were local accommodations that provided a ‘home’ abroad and the opportunity to get to know a local family. Although my bags came home a bit heaver from each leg of my journey, filled with new books and other keepsakes, a few pieces never made the trek home: I entirely wore down the treads on two pairs of hiking boots and three pairs of sneakers, logging about 2,500 miles on foot over the course of the year. Most of my days during the fellowship year were spent in the field, exploring new sites, but I also treasured the time that I spent in local libraries, laundromats, and coffee shops, reading about the local area, reflecting on the travels, and crafting the SAH research blog entries. These were essential moments of pause amid a year that can be classified as a wonderful yet intense visual overload. These quiet times for reading, writing, and processing photographs and videos provided valuable perspective and time to contemplate the extremes that I encountered on the various islands: the possibility of speeding around Japan on bullet trains at 200 mph while it took nearly six hours to traverse thirty miles of a winding gravel road in Iceland’s Westfjords, or the fact that I had clear and strong cellular service in the middle of the Norwegian Sea but had difficulty loading a text-based email when I was in Cuba after waiting nearly two hours to purchase a 30-minute internet card (Figure 2).

The wonders (and perils) of fieldwork included getting stuck in all types of weather, getting lost, and enjoying priceless moments of serendipity, such as discovering how local animals interacted with their native built and natural environments. From left to right, one of the many dachshunds of Santiago de Cuba testing a resting place in a concrete wall, sheep precariously perched on a gravel island in Iceland, and a Japanese macaque finding a hiding place for snacks in Arashiyama.

Overall, my time in the various islands proved that the built landscape of tourism can be a problematic one, flooding unequipped areas with cars and buses while visitors search in vain for trashcans and water closets. Although many heritage sites leverage existing resources, the island subjects of my study proved that there are many unanswered questions related to the management of heritage: how can sites deal with accessibility and aging travelers, and should there be limitations on tourism, despite the potential economic benefit? At this point, I envision that many of the theories I developed in reference to sustainable tourism at cultural heritage sites will need time to incubate and I hope that I will have the opportunity to revisit several sites in five years to see transformations currently in progress, such as Reykjavik's new skyline, the work of BIG in the Faroe Islands, Cuba after a boom of foreign, 5-star hotel investments, and Japan after several international events in the capital and a new commitment to green energy.

During my year abroad there were also significant changes in relation to my study of the impact of tourism on cultural heritage sites. For example, Iceland developed the do-no-harm ‘tourist pledge’ and in mid-June the U.S. government enacted policy changes for Americans hoping to visit Cuba. Under the new regulations, my extended and independent travels in Cuba would have been impossible so my time in the nation seems even more precious now. Although I embarked on a version of ‘slow’ tourism, I was an active subject within my own study but my travels underscored that the bucket list approach to tourism can be highly problematic because tourists can miss opportunities for cultural immersion and through their truncated visits to sites those visitors do not take time to consider changes in the landscape or how their actions, carelessly wielding selfies sticks or moving away from marked paths, can have detrimental impacts on preservation and conservation efforts.

Technology and Architectural Record

Over the course of the fellowship I learned to travel lightly but nearly half of my ‘kit’ was dedicated to the tools of documentation, ranging from sketchbooks and an array of drawing instruments to accessories and lenses for my DSLR and GoPro. During certain legs of my travels where aerial documentation was permitted, I was also carrying a UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle; drone): either a DJI Phantom 4 or the more portable DJI Mavic Pro. Alongside these digital tools was another compliment of cords, adapters, a laptop for processing, and external hard drives to maintain a fastidious system of backups for the gigabytes of data that I captured, daily, through various devices (Figure 3). File organization, naming, metadata tagging, and archiving occupied more hours than I could imagine, but I managed to develop a workflow during the fellowship that I know will be valuable for many years to come (Figure 4). This consisted of meticulous note taking, usually on my phone with Microsoft OneNote, to keep track of my daily activities: names of sites, navigation notes, and initial reflections on sites. CamScanner, as noted in previous blog posts, was also extremely useful for documentation in museums. In terms of processing all of images captured with my DSLR, Adobe Lightroom was absolutely invaluable as a digital darkroom for RAW images.

Figure 3. An array of digital kit: Canon 80D DSLR with wide angle and telephoto lenses, Manfrotto compact tripod, a GoPro Hero 4, DJI Phantom 4 and Mavic Pro with extra batteries and adapters, MacBook Pro, external hard drives, protective hardcases, and various accessories.

Figure 4. Icons for the programs that were invaluable on the fellowship for image processing and data management (from left to right): Adobe Photoshop CC, Adobe Lightroom CC, CamScanner, and Microsoft OneNote.

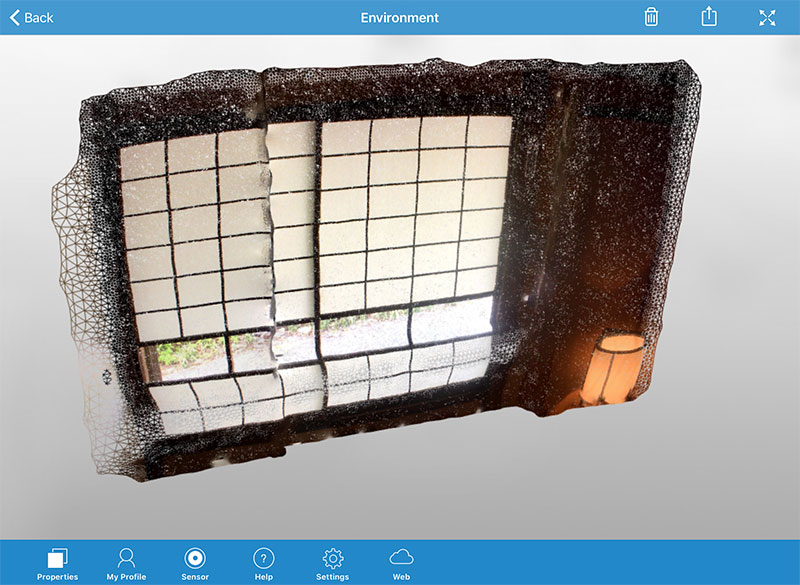

During the second half of the fellowship I experimented with a handheld 3D scanner by Structure Sensor for small-scale photogrammetry projects. As much as I am an active proponent of the integration of new technology in architectural documentation, my experiments produced little more than frustration (Figure 5). Unless one is able to travel with a full compliment of equipment, ranging from about $30,000–150,000, the available handheld scanners are not yet equipped to accurately capture architectural environments and they are best used for small scale, object-based studies such as a sculptural bust on a plinth. Although I was initially excited to capture connection details, I quickly discovered that small scanners cannot capture anything much larger than 100 square feet and they frequently overheat in sunny conditions.

Figure 5. An attempted scan of a simple screen wall at the House of Ogai Mori and Soseki Natsume (1887), representative of a middle class residence in the Meiji era, in Meiji-mura, captured with a Structure Sensor and processed with itSeez3D.

In terms of spatial limitations, there were occasions where interior corners could be recorded but these often yielded skewed results proving that the scanner needs to operate within even, studio lighting. For this reason, capturing an exterior corner condition was nearly impossible. In Japan I discovered another complication. Here, interior spaces have rich chiaroscuro and layers of shadows; yet, these qualities that are so intriguing in person are lost in the translation from real space to digital space. The resultant model contained distorting 'holes' from captured shadows since there is no infrared information to populate the model space. Documentation is further complicated by the fact that the scanner has difficulty processing glass, water, or flat surfaces (e.g. even plaster walls); and any movement distorts the captured image so a small gust of wind through surrounding trees or the passing of other visitors suddenly renders a model sequence unusable. A tripod can help negate some of these issues but they are typically prohibited at museums and religious sites.

In Iceland and the Faroe Islands, the vast expanses of land and relatively open aviation laws allowed for the use of a drone to capture landscapes and select buildings outside of the capital. This, however, was not an option in the nationwide 'no fly zone' of Cuba and drone use is very restricted in Japan: drones are prohibited in all national parks and in major cities such as Tokyo. I was, however, able to get permission to fly over one of Japan's open-air architectural museums, the Hokkaido Historical Village outside of Sapporo, and I will be working with the data captured to model a historic photography studio as well as a prefabricated barn that is currently undergoing restoration after a roof collapse (Figure 6). Although much of my experimentations with a handheld scanner proved fruitless and drone technology related to architectural documentation and analysis is very much in development (and in tension with evolving regulations), it is exciting to think of what may be available in five to ten years, allowing designers and historians to record and analyze spaces in new ways through portable, unobtrusive hardware and more streamlined and sophisticated software.

Figure 6. An aerial view of the Hokkaido Historical Village outside of Sapporo, Japan. Under the right legal and weather conditions, the use of drones can offer an entirely new way of seeing, recording and analyzing the built environment.

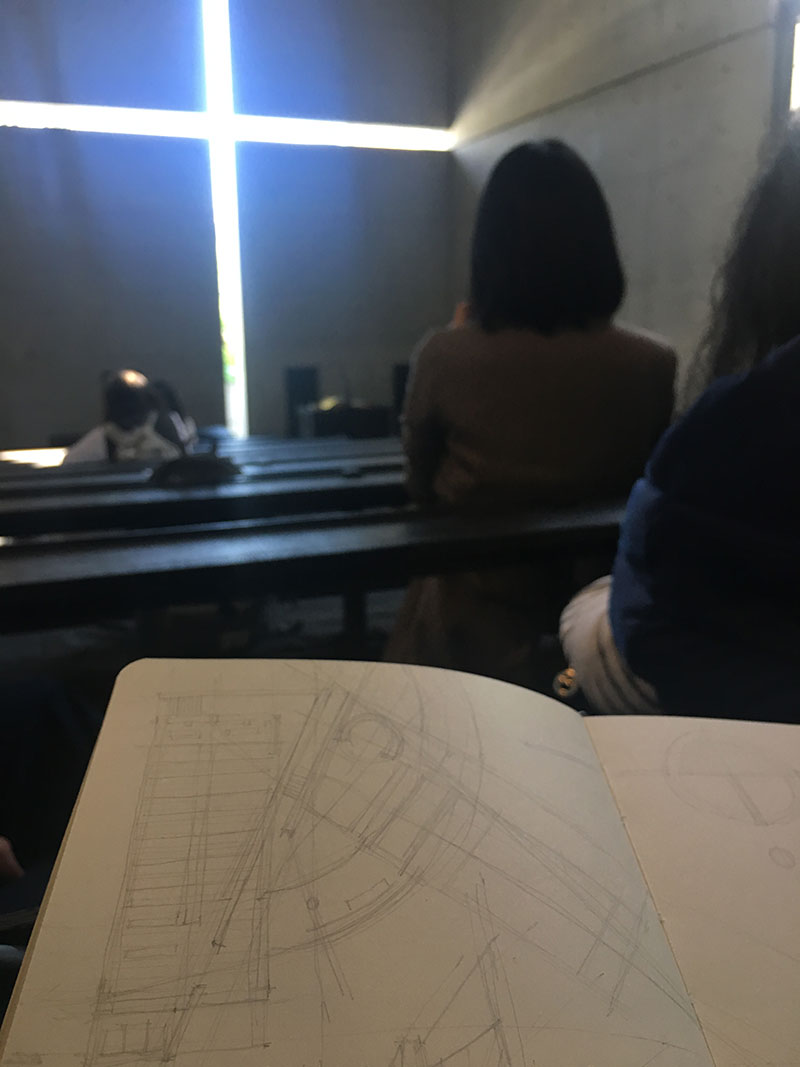

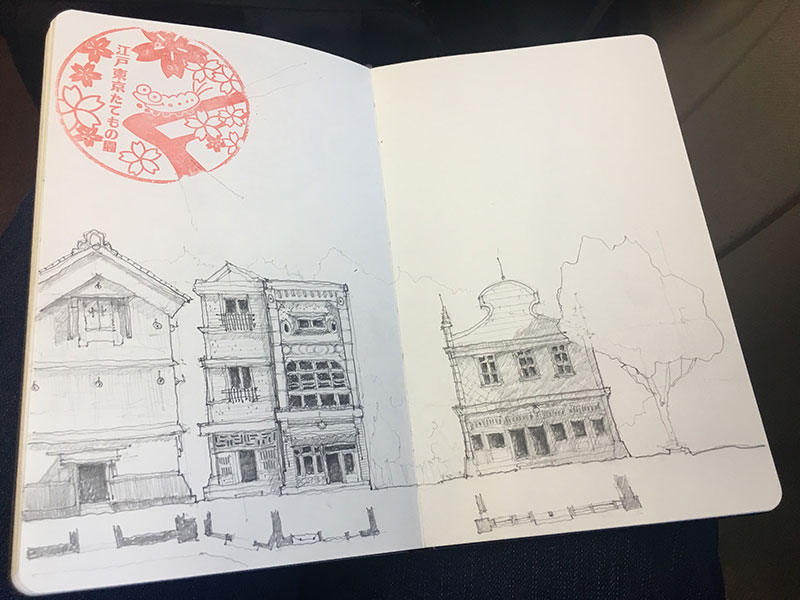

Although I would not trade any of my technical kit or the gigabytes captured, one of the most valuable tools during my travels was the least sophisticated: a sketchbook. Travels sponsored by the fellowship renewed my dedication to the phrase that, ‘you do not understand a building until you draw it.’ Despite advancements in tablet technology and even augmented reality, it is difficult to image another tool as useful and dynamic as a sketchbook for investigating a site, processing initial impressions, and collecting small pieces of ephemera (Figure 7-10).

Figure 7. A few of the many sketchbooks from a year of traveling, plastered with local stickers to identify the contents.

Figure 8. Deciphering the plan on-site in Ando’s Church of Light.

Figure 9. Studying light and elevation organization in the recreated ‘townscape’ of the Edo-Tokyo Open Air Architectural Museum, complete with an impression of the site’s identifying stamp in the upper left corner.

Figure 10. A view of the many internet cards used during my time in Cuba alongside a local, 10 CUP note (approximately 24 CUP = 1 CUC).

Final Notes

I cannot express enough thanks to the Society of Architectural Historians and the H. Allen Brooks endowment for such an incredible experience. Auburn University, and in particular the School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture, has been very supportive during my external research leave and recognized the fellowship as both an unparalleled opportunity for a tenure-track Assistant Professor and a chance to develop research agendas for architectural studios and field studies. Throughout this process, friends and colleagues were generous with their time and expertise, answering calls and emails at all hours to provide feedback on travel plans and technological advice. In addition to balancing affairs at home, my parents can be thanked (or blamed?) for instilling an insatiable love of travel, museums, and history. Despite careers outside of the study or creation of the built environment, they warmly welcome even the most obscure, architecturally motivated excursions. Above all else, this year has been an ongoing lesson in what incredible sites and people this world has to offer, especially to travelers who explore with an open and inquisitive mind.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top