-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

The Dome as Ornament

Deyemi Akande is the 2016 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

Since the start of my tours, I have only had the opportunity to see cathedrals of the Gothic genre. So you can imagine my delight as I made my way to the Berlin Cathedral. Camera in hand without a care in the world, I had the mien of a kid going to a candy store. I must confess, more than anything I have come to see, the cathedral dome remains priority. One is often overtaken by a concoction of emotions as one looks straight up at the epicentre of a finely crafted dome and needless to say, in Berlin, I was not disappointed. The dome, sometimes elliptical but mostly circular, does wonders to changing the spiritual character of any interior. Theresa Grupico describes the circle as a form having no beginning and no end, reflecting perfection, the eternal, and also the heavens.1 Like Grupico, many scholars suggest the dome symbolises heaven; heaven is indeed what you feel when you see the great central domes of German cathedrals.

Fig. 1: Looking up into ‘Heaven’. My view of the central dome of Berlin Cathedral from the nave floor.

Fig. 2: A view of the dome above the chancel from the nave in Berlin Cathedral. At the top of the arch, two angels hold a decorated plaque with the inscription (in German) “Be reconciled to God.”

Fig. 3: An exterior view of the central dome of Berlin Cathedral framed by two trees as seen from across the Spreekanal.

Fig. 4: A view of the central inner dome of Dresden Cathedral (Frauenkirche) from the nave. This dome is 26 meters above the church interior and the paintings were (redone) by Dresden artist Christoph Wetzel.

Fig. 5: A view of the central inner dome of Dresden Cathedral (Frauenkirche) from the elevated access stairs in the dome. Pews from the nave (first floor) can be seen here.

Fig. 6: An exterior view of the main dome of Dresden Cathedral.

Now inside the Berlin Cathedral and as I gradually got transfixed looking up at the dome’s magnificent eight mosaics pieces, a soothing voice came through the public address system from the gallery saying Guten morgen, willkommen im Haus Gottes. It was a female cleric, she stood near the white marble and yellow onyx altar and repeated those words in English and in French. We were invited to sit for a brief moment to partake in a short service where a prayer for peace on earth would be said. Soon enough the hall went quiet and we were all enamoured by the sweet voice of the speaker for about two minutes. Her sermon was entirely in German and I, understanding not a single word she uttered but enjoying the astonishing glory of the mosaics in the dome from where I sat, found the sermon altogether pleasing nonetheless. She called out again in English and French, inviting all present to join in our native languages as the congregation recited The Lord’s Prayer. At first it was like the rumbling sound of charging horses but eventually a synchronised rhythm was reached even as we all spoke in different tongues. At the end came a loud ‘amen.’ Now there was silence and then it happened—the great organ rang out in the most grandiloquent manner giving a melodic and rather ornamented rendition of "Nun danket alle Gott" (Now Thank We All Our God)—I broke down in uncontrollable tears. It was without contest the most beautiful sound my ears ever heard.

Trying to arrest the situation I found myself, I quickly sat (while others stood) and put my head on the pew in front of me as if in prayer. I was not in prayer, rather I was deeply confused as to why I would, without any warning whatever break down so severely in tears. In some ways like the wall of Berlin came crashing on that still night of the 9th of November 1989, I find a sort of wall crumble around me too. Such relief, such peace, I felt, such weight appeared to have been lifted off my shoulders. I must be honest, I am still at a loss for an accurate explanation for this happening.

Here I was, a full grown man, having no control whatsoever over self as tears stream (no, tumble) down my cheeks with careless tenacity. It must have been quite a sight for the people around me who caught a glimpse. They, being in an awkward position of not knowing if to approach me to enquire about my state or not. Thankfully, no one did. I wonder how much more awkward it may have turned out if after being asked why I was in such state of despair, I reply I have absolutely no idea why. I imagine they would have resolved in their minds that it must be the gorgeousness of the place that has brought out the soft side of me—for the most part, I would not argue the contrary. I would however wager that in addition to the already mentioned, the overwhelming sound of the organ may also have a thing to do with it. Likewise, the completeness of the architecture that surrounds you with faultless splendour just makes you want to exhale.

Whatever it was, it got me well and the interior of the Berlin Cathedral acted as a conduit for the transmission of positive energy. Such is the power of ‘honest’ architecture, it resonates with our innermost place of emotion and sometimes serve as a catalyst to the breaking down of walls we may not even realise was present about us.

Fig. 7: The great Sauer organ of the Berlin Cathedral with its 7269 pipes. An impressive piece of work with the most amazing sound.

Fig. 8: Another view of the great organ inside the Berlin Cathedral.

Fig. 9: Inside view of the central dome of the Berlin Cathedral showing the Beatitudes crafted into the eight segments of the dome and the surround clerestory windows that bathe the inner dome with immaculate light from the skies. The mosaic work is designed by Anton Von Wermer.

Fig. 10: Part of the central dome of the Berlin Cathedral and one of the four semi-circular niches in the predigtkirche showing the evangelist Marcus (Mark).

Fig. 11: The beautifully ornate pulpit carved from oak wood and gilded. The pulpit was designed by Otto Raschdorff, the son of Julius Carl the cathedral construction chief. The work was completed in 1907.

Fig. 12: The Berlin Cathedral, a view from the West Side. The Lustgarten is seen in the foregrounds.

Fig. 13: The main cross on top of Berlin Cathedral and details of a second cross with statue of angels looking on from both flanks on the main entrance of the west side.

Fig. 14: Main door way of the western side of the Berlin Cathedral. The mosaic above the entrance shows Christ as healer of the infirm; here the inscription says “come unto me all you that are weary and burdened and I will give you rest.” This mosaic work was done by Arthur Kampf, ca. 1920. On the ceiling of the 9-meter-wide triumphal arch is another series of brilliant mosaic works. The central piece is a dove, the Christian symbol of peace.

Fig. 15: The beautifully ornate arched ceiling features three mosaic works. To the left is the Holy Chalice, the center features a dove and the right side features the crown of thorns.

Fig. 16: A copper statue of Christ blessing the city of Berlin. This piece was sculpted by Fritz Schapper. Atop this is an ornate cross with angels on either side looking up in adoration.

Fig. 17: The faceless woman. An interesting sculptural piece inside the Berlin Cathedral.

Many cathedrals I have visited metaphorically feature three levels; the first is the crypt–a vestige of the past and a representation of the imminent end to all. The crypt however also stands as an abstracted reminder of a renewed hope that gives a new life and a new beginning to every ending. The second is the cathedral nave—a solid and tangible presence, the physical reality of our current existence and an expression of the glory of life in continuum. The last and most lofty level I will call the floaters. These are the architectural elements that defy the reality of the tangible level. The dome being the most elevated of this level is to me the predictive manifestation of a possible future. The dome serves as a metaphor for power over impossibilities. The physical structure often embodies a message that challenges our imagination in a way that inspires hope and nudges us to continue to venture, to build, and to excel. This is a central message I see in all domes. The dome has a long history and no mainstream religion or architectural philosophy can lay claims to it as it transcends through time and style. Again Grupico points out: the architectural design of circular dome over square base was used in both churches (Hagia Sophia) and mosques (that of Suleyman the Great) but the idea is rooted in even earlier architectural traditions such as pre-Islamic Persian tombs and fire temples. The symbolism of these geometric forms is itself rooted in mystical thought dating back to Plato and Pythagoras.2 The success of the dome as a structural and symbolic choice can perhaps be credited to the figurative message it carries, meaning one thing to one and another thing to the other.

In all, I see the dome as a structural rhetoric and ornament that gives life to the ideology that encourages the mind of man to approach all impossibility as in fact a potential probability.

Fig. 18: The domes of Berlin Cathedral as seen from the Schlossbrucke Bridge across the Spreekanal. To the right is the Berlin Fernsehturm (Television Tower).

Fig. 19: The cross atop the lantern on the central dome of Berlin Cathedral.

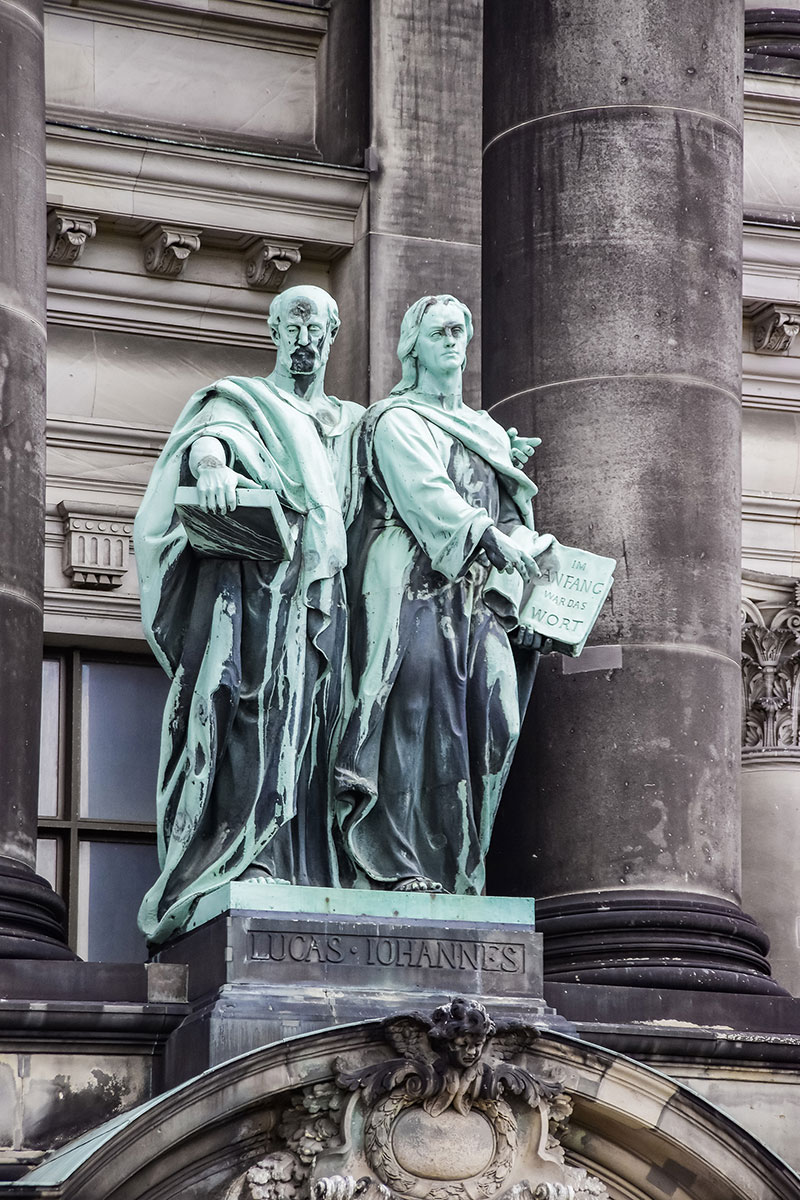

Fig. 20: Copper statues of disciples Luke and John designed by Gerhard Janensch and Johannes Gotz.

Fig. 21: Copper statues of disciples Matthew and Mark designed by Gerhard Janensch and Johannes Gotz.

Fig. 22: In the foreground, the reverse side of a street sculpture and in the background is the dome of the Dresden Cathedral. The sculpture mounted on a water cistern and drinking tap in a nearby street faces the direction of the cathedral.

Where there is a dome, there is almost certainly a transition point from where the circular base connects with column often in a square formation. The magic of the pendentive thus come into play. As early as the Byzantine era, architects have been smart not to let the surface area of the pendentive go to waste. In fact, the triangular transition has become one of the most strategic surfaces in a domed building to feature the most intense symbolic art and ornamentation.

Baroque and Renaissance architects have taken this practise to new heights and directions. The sort of opulent ornamentation seen in the Berlin cathedral will at some time in the past be heavily criticised especially within the context of the Roman Catholic Church. One such strong condemnation of richly details and vibrantly coloured ornamentation in churches was by Puritan preacher Jeremiah Dyke who referred to the Roman Catholic Church as the apocalyptic whore and to the churches of Rome as the slut’s adornment, distracting and deceiving through the senses.3 By the turn of the 20th century however, I think we had generally come to terms with it as an expression and symbolic representation of worship and adoration to the higher power who makes all possible through abundant riches in glory.

Architectural history today frequently seek to interpret buildings as objects shaped by and expressive of their social meanings and historical contexts. It would be both modest and commendable to decide that the best way to grasp the realities of an old church for instance, is to chart the competing economic, political, religious, and cultural forces that brought it into being and to interpret it as a material expression of the ascending wealth during the period.4 Both the Berlin and Dresden Cathedrals feature the most amazing ornamental arts on and around their pendentives as it transitions into columnar systems that transmits the energy from the dome downwards.

Fig. 23: Saint Matthew’s semi-circular niche in the predigtkirche of Berlin Cathedral. Flanked by statues of Philipp Melanchthon; humanist and German reformer sculpted by Friedrich Pfannschmidt and John Calvin; lawyer and French reformer sculpted by Alexandrer Calandrelli. Bas relief sculpture is seen on the surface of the pendentive area.

Fig. 24: A statue of Phil.D.Grossm (Philipp the Magnanimous)–Landgrave of Hess. The piece was sculpted by Walter Schott.

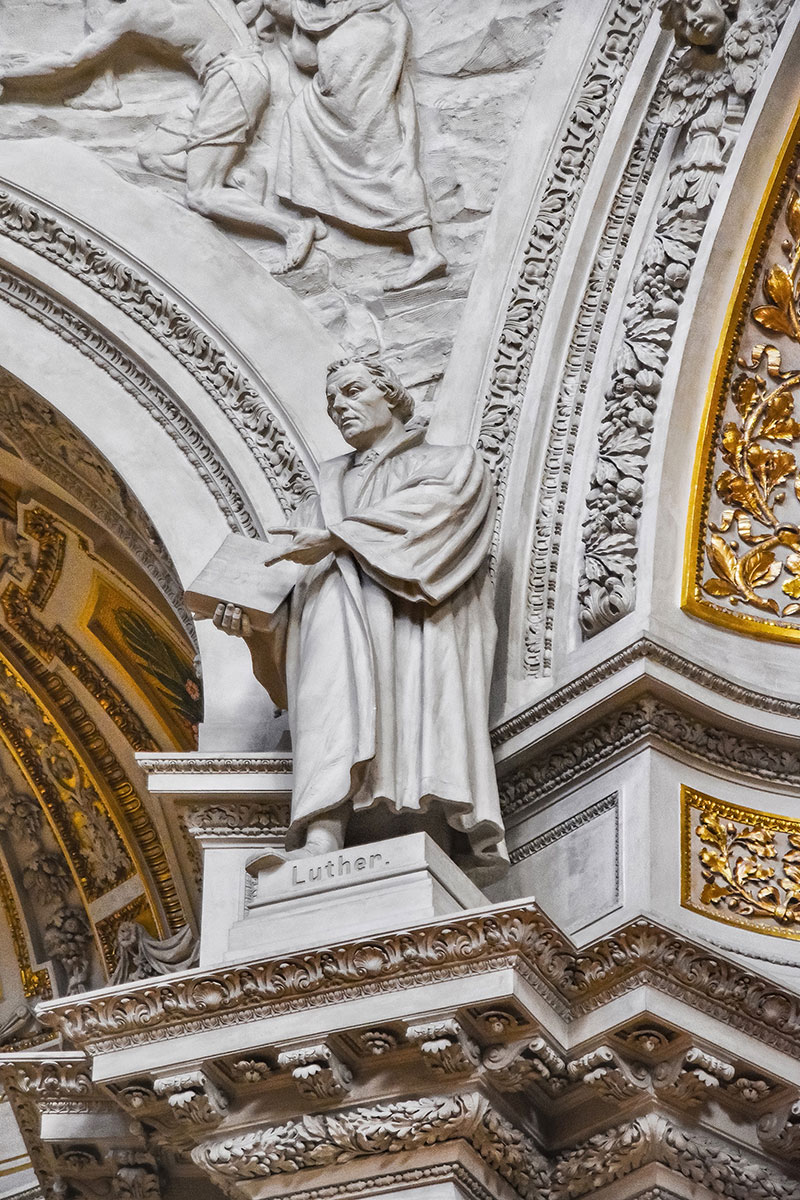

Fig. 25: A statue of Martin Luther–theologian and reformer. Sculpture by Friedrich Pfannschmidt

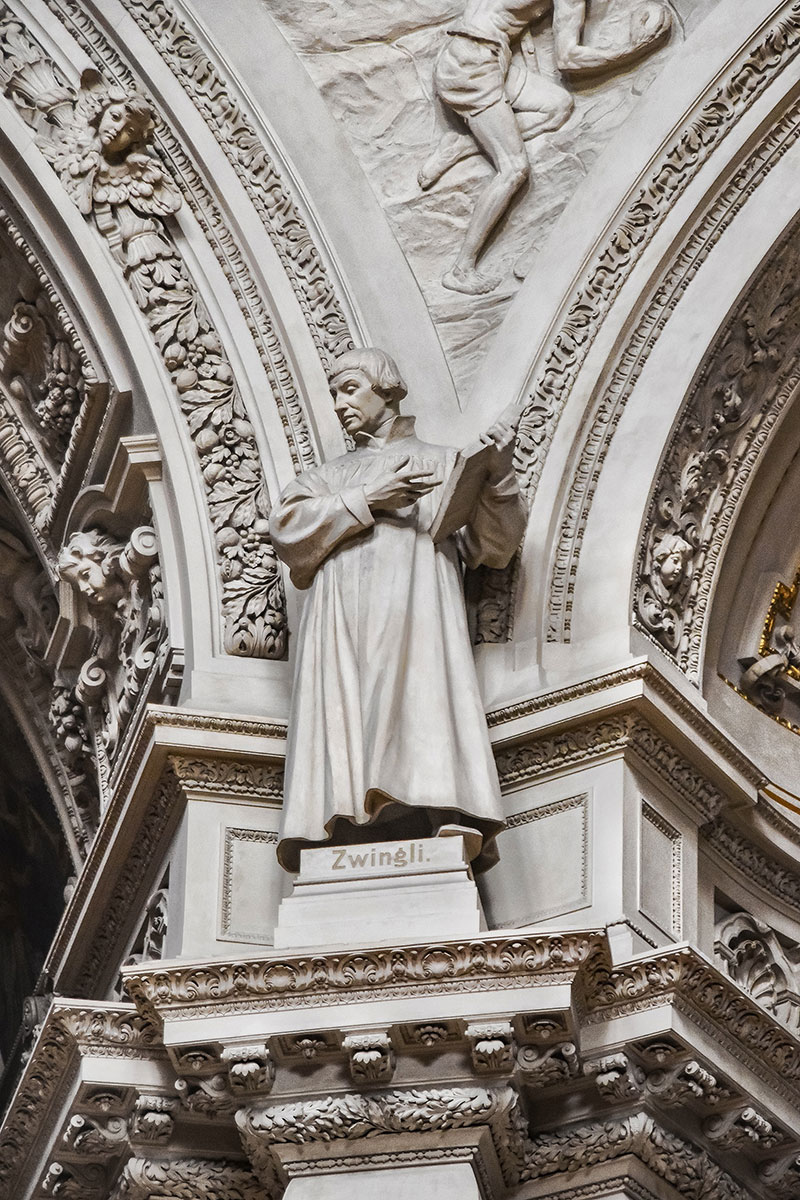

Fig. 26: A statue of Ulrich Zwingli, a theologian and swizz reformer. This piece was sculpted by Gerhard Janensch.

Fig. 27: Part of the central dome and Saint Mark’s niche. The pendentive area here is also covered in Bas relief sculpture.

Fig. 28: A gathering of Corinthian columns. Heavily ornate capitals receive the thrust from the vaults and transfers the energy through the columns down to the earth.

Fig. 29: Part of the central dome and details of the adjoining ornate ceiling.

Fig. 30: View of the chancel from the nave. Bas relief sculpture decorates the pendentive areas between the niche and the central dome.

Notes on the Cathedrals: Oberpfarr– Und Domikirche zu Berlin (Berlin Cathedral) and the Frauenkirche (Dresden Cathedral).

Berlin is a very special place. It is not one of the oldest cities in Germany but during the last 500 years, all political and cultural developments left their legacy on the city. The architecture reflects not only developments in art but also in technology and society. German architecture generally mirrors the changes and upheavals in Central Europe in the chequered way of the centuries.5 In Berlin, a historically important city, we find Berlin Cathedral, also known as the Berliner Dom. Like all other cathedrals I have visited, it has an almost 500-year-long history of development and transformations. The building’s story begins in 1465, when the Elector of Brandenburg Friedrich II conferred the rights of a cathedral on the chapel in his palace. The 6th Elector Joachim II moved the cathedral to the old Dominican monastery (Schwarzes Kolster) close to the palace and in the same 1465 gave it a charter as the palace and court church and the ruling family sepulchre.6 Like many cathedrals also, the Berlin Cathedral has waded through difficult times. On the 24th of May 1944 a fire bomb hit the dome of the famous cathedral that was then called the Kaiserdom. The cathedral was greatly destroyed as the dome collapsed into the floor of the nave breaking through to cause serious damage to the crypt below. The gaping hole was not to be fixed for years, allowing the elements in—until 1953 when the dome was patched. The central dome on the Berlin Cathedral has an array of windows around it and on a sunny day the light from the windows rushes in and bathes the dome in such light that makes it appear to be floating in mid-air. The dome features eight beautifully crafted mosaic pieces depicting the Beatitudes as proclaimed by Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount. Designed by the renowned artist Anton Von Werner, the works are indeed of masterful craftsmanship and a sight to behold. The mosaic is considered to be among the very best examples of mosaic craft anywhere in the world. The works are composed of about 500,000 small tiles and around 2000 different colours. There are 16 different hues of gold alone, combined to create a realistic tapestry of shades.7 The visuals are extremely detailed and expressive. The cathedral organ is by all standards a musical monster. Boasting of an impressive 7,269 pipes and 113 registers, masters say she has the same tonal characteristics as a symphony orchestra. On top of the organ is a golden statue of King David. At the statue’s feet is a young David playing the harp for King Saul. This symbolic piece of art situated on the great Sauer organ does speak volumes. Little wonder, the organ’s production has such profound effects on the listener.

The case of the Dresden Dom is no less enigmatic. The fantastic structure got a mention in Martin Briggs seminal material on Baroque Architecture. Briggs states that Frauenkirche, though not belonging to the Baroque style as such, has however not forsaken the boldness of Baroque design for (as he puts it) architectural confectionery.8 The Dresden Cathedral, also known as the Frauenkirche Dresden (Church of Our Lady) is an example of a building that means everything to its people. The structure we see today is an admixture of two eras. Like the Berlin Cathedral, the Frauenkirche, which was originally completed in 1743, suffered a deadly blow from WWII bombs. The burnt cathedral collapsed on itself on 15 February 194—two days after it was bombed. The ruins were to be a painful wound in the hearts of the people of Dresden for an unimaginable 45 years! Calls to rebuild the Frauenkirche intensified in the early 1990s, and what we see today is a product of the relentless efforts of the Dresden people giving donations to the 1994 Frauenkirche Dresden Foundation to take up the task of rebuilding the pride of the Dresden city. As Gulani (2005) puts it, the architecturally extraordinary (Baroque) church designed by Master Builder George Bahr was an integral part of the famous Dresden silhouette.9

A brilliant innovation is to be seen on the ‘new’ building—an unyielding part of the original structure that was not conquered by fire nor the horror of the bombs remains till today. A standing wing from the old cathedral was reintegrated into the new structure. Today you will see the Dresden Cathedral with an emblematic old dark ‘scar’ that reminds us all of its experience. The fusing of the old and the new is in my opinion ingenious and rather emotional. Visually, the Frauenkirche is a two-in-one structure that carries on the wisdom of the old and innovation of the new. So when asked how old the Frauenkirche Dresden is, I imagine it will be a tricky question to answer considering that it has the sine and fibre of two eras standing together as one. The newer structure was built to the specifications of the original design using the historical plans of master builder George Bahr.

The central dome of the Frauenkirche—like that of Berlin Cathedral—is divided into eight segments, eight being a sacred and symbolic figure in Christian numerology. Four of the eight segments of the dome feature Evangelists Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, while the other four visually extol the Christian virtues of Faith, Love, Hope, and Charity. The original painting of the inner dome was done by Giovanni Battista Grone of Venice in 1734. The beautiful rendition we see today was masterfully recreated by Dresden artist Christopher Wetzel. Wetzel’s recreation is often famed to be a perfect remaking of the original piece. The altar of the Frauenkirche also deserves a mention. Besides the dome, the altar is an imposing and central element that commands significant attention. The baroque style altar was sculpted by Christian Feige and is made up of over 2,000 fragments. The central feature is a scene of Jesus in prayers on the Mount Olive with His disciples fast asleep. Garlands of wheat and grapes extend from either side of the piece while the cathedral organ, which is seen above the altar, gives strength to the composition with the strong visible lines delineated by the organ pipes.

Fig. 31: The Frauenkirche (Dresden Cathedral)–an exterior view.

Fig. 32: A view of the Dresden Cathedral’s altar from the nave. The baroque alter was sculpted from sandstone by Johann Christian Feige based on the design by master builder George Bahr.

Fig. 33: Details of the organ pipes integrated into the altar design.

Fig. 34: Part of the cathedral’s central dome showing its transition through pendentives into columns. In the center is the cathedral altar.

Fig. 35: An opening on the inside of the main dome (23.75 m above the nave) that allows visitors to see portions of the nave below.

Fig. 36: The patch that survived the bombing. A patch of the 18th-century original structure integrated into the new building.

Fig. 37: A portion of the old wall now free standing near the Gate G of the Dresden Cathedral.

Fig. 38: The top cross mounted on the lantern on top of the central dome of the Dresden Cathedral. The cross alone is 5.2 meters (17 feet) tall. This new cross was donated by the people of Britain to the Frauenkirche in 2000 on the 55th anniversary of the bombing of Dresden. The design is based on the old cross that was destroyed in the bombing.

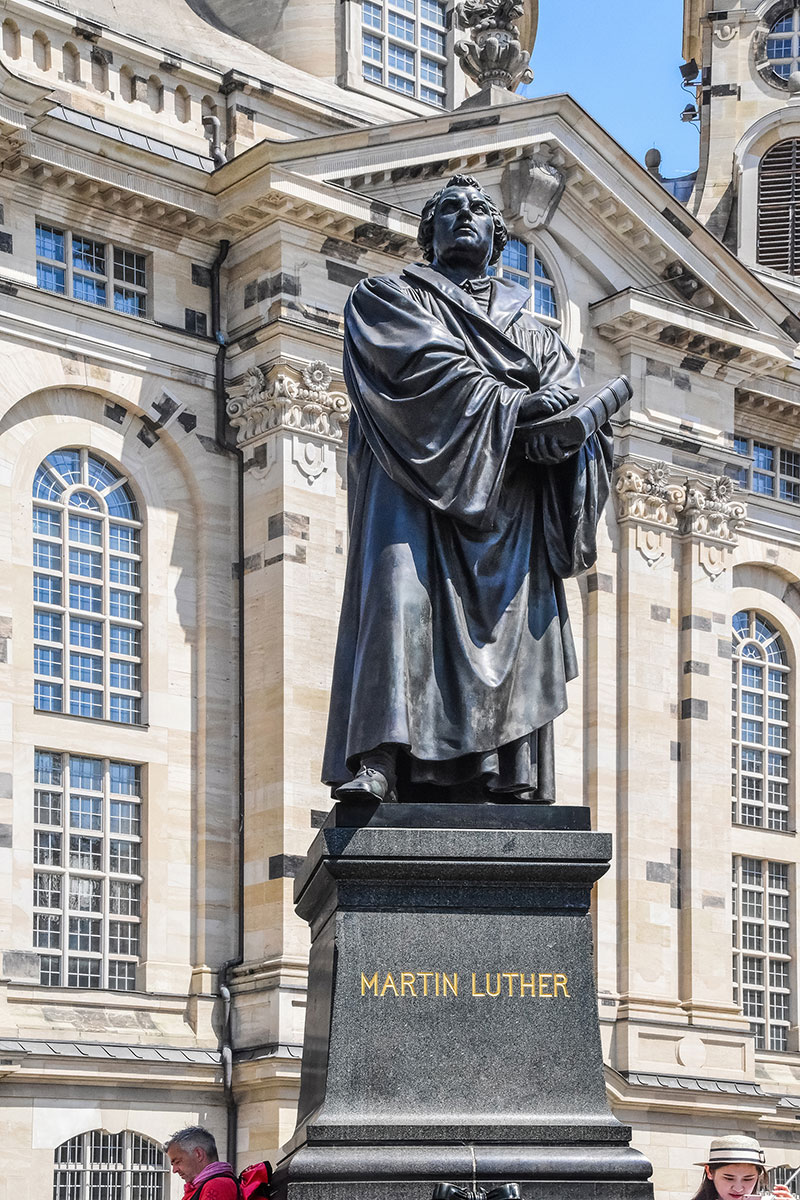

Fig. 39: A statue of Martin Luther, the renowned theologian and German church reformer, in front of the Frauenkirche.

Fig. 40: Fountain adjacent to the Frauenkirche Dresden.

Fig. 41: A view of the fountain from the rear with the Frauenkirche Dresden in the background.

Fig. 42: Close up of one of the four stair tower on the Dresden Cathedral.

Fig. 43: Close up of the pinnacle of one of the stairs tower with the ‘butterfly’ stone at the base.

Fig. 44: The Frauenkirche Dresden at dusk.

A Hint of the Colour Gold

A thing that catches your eye in parts of Germany is the use of the colour gold. A hitherto sombre sandstone building suddenly jumps to life with a touch of gold added to it. Every now and then one sees a structure with a golden statue on top or a dash of gold used for ornamentation. The gold gives a lovely shimmer in the sun and brings attention to the building. It was not tough at all to see a feature of gold everywhere I went and like the biblical Passover sign where buildings were marked in blood, here the building seem to be marked in gold as if to say if you see the gold thou shall pay attention to me. It would appear that everything that deserves any attention or an investment of one’s time has a gold mark of some sort on it. This is not to suggest however that for something to be important it must have a feature of gold on it—far from it—it is just that everything that has a feature of gold on it is in fact important and carry an appearance about them worthy of some attention. Indeed, when you see gold, you will know the building is important.

Fig. 45: Ornate onion-shaped dome with gold leaves design. Dresden Castle, Dresden.

Fig. 46: A beautiful golden cherub with a fire touch atop the Academy of Fine Arts, Dresden

Fig. 47: Baroque style ornate crest on the main entrance way of the Academy of Fine Arts, Dresden.

Fig. 48: Golden cross spherical ball atop a Roman Catholic Cathedral tower in Dresden.

Fig. 49: Golden angel statue on top of the dome of the Lipsius Building.

Fig. 50: Sitting cherub with a star-point wand atop the Academy of Fine Arts, Dresden

Fig. 51: A dash of gold on a sandstone building, Berlin.

I will draw the curtain here for Germany and move on to my next location. I have thoroughly enjoyed my stay in Germany but if asked, above all others, I would vote Dresden as a place I must return to. Dresden was a rather friendly and warm place even for a single black male traveller like me. The ‘single black male’ carries the stigma of several negative stereotypes. I was not exempted from the unpleasant experience and subjective actions of these stereotypes, particularly in Berlin, but despite the sinking feeling and sometimes downright annoyance one feels when people see you and suddenly secure their purses, bags, and infants in a way to suggest you must be a thief or a danger to their safety on account of your colour, in Dresden, you will often still find yourself sharing a smile and a ‘hallo’ with a passer-by, and how I enjoy such fleeting moments. They quite frankly ornament life and add value to small times. When one thinks about it, that one may never see those people again, it does give such priceless value to that small smile on a small street in a small town. The smiles in Dresden, however, does not totally remove that fact that in some parts of Europe—speaking of the colour gold—the locals mostly miss it, however apparent it is, because of the dark shade of fear that constantly blocks the sun from making the gold shimmer. Many cities lack the soul of friendship, and do not see the dash of gold that clearly adorns your well-toned ebony skin. I make proud to say, Dresden isn’t one of them.

Fig. 52: A view of the Elbe River and Dresden countryside from the 67-meters-high viewing platform of the Frauenkirche.

Fig. 53: An aerial view from the Frauenkirche viewing platform. In view is the Transport Museum in Dresden (cream building with off white roof), the Furstenzug (impressive large porcelain mosaic of Saxon rulers on wall of narrow building to the left of the road on the upper right), part of the Dresden High Court (top right corner of the frame) and Dresden Tourism Information Office housed with other private property, hotels, and restaurants in the foreground (brick coloured roof).

Fig. 54: Evening shot overlooking the Culture Palace where the Dresden Philharmonic is housed.

Note:

The Hymn "Nun danket alle Gott" (Now Thank We All Our God) was written by the German composer Martin Rinkart in c. 1636. The hymn is believed to have been written around the end of the Thirty Years' War.

1 Grupico Theresa, “The Dome in Christian and Islamic Sacred Architecture,” Forum on Public Policy: A Journal of the Oxford Round Table Vol. 2011 Issue 3, Special section (2011): 8

3 Morel, A-F, “The Ethics and Aesthetics of Architecture: The Anglican Reception of Roman Baroque Churches,” Architectural Histories Vol. 4(1), No. 17 (2016): 2. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/ah.75 accessed July 20, 2017

4 Anne-Marie Sankovitch, “Structure/Ornament and the Modern Figuration of Architecture,” Art Bulletin Vol. 29, No. 4 (1998): 687

5 Marcus Hackle, “Identity And German Architecture: Views of a German Architect,” accessed July 14, 2017.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top