-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Decorated Vault Ceilings in British Cathedrals

Deyemi Akande is the 2016 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

If Gothic vaults were a topic at a roundtable, many would be disposed to discuss their structural brilliance, leaving only little space for the appreciation of them as art. I, quite frankly, agree that the virtuosity of a vault system is probably more recognized as a structural feat than an ornamental one, but in spite of the obvious, I am inclined to see the beauty of the structure first before exploring the structure of the beauty. From where I stand, and with only little apologies to offer for my pitiable zeal for construction talks, all I see up there is the beautiful art of the vault.

They say Gothic cathedrals mimic the great forests of nature. That the columns and piers are tall straight trees that line the untouched woods piercing the mists that settle over the skies; the very breath of God they say. They say the branches spreading out from the trunks making a canopy over the grounds of the forests are vaults. Just like in nature, as the branches get their nourishment through the trunk, the vaults get their strength and stability from the piers. The vaults are indeed a stately expression of the delicate balance of weight and space playing out in a sort of figurative performance.

If I could, I will risk an article of only a few words, presenting my silence as the utmost reverence for not just the remarkable ingenuity and audacity of the early builders, but also to the temerity of the artist who painstakingly decorated some the vault ceilings. But, words are indeed a must for me to describe what I see, though I am almost certain that they may be inadequate. Thus, photography must here help to convey the beautiful wonders of the intricacy of vaults as best as it can.

Fig. 1: Decorated 13th-century wooden vault ceiling hanging above the high altar in St Albans Cathedral. Redecorated in the 15th century by Abbot Wheathampstead with badges of patron saints and family shields of other patrons who contributed money to the repair of the cathedral.

Fig. 2: Decorated vaulted ceiling of the transept in Salisbury Cathedral.

Fig. 3: Decorated vaulted ceiling in Salisbury Cathedral showing three different patterns and design.

Fig. 4: Though not of Gothic Style, the decorated ceiling vault of St Paul’s Cathedral is one of the finest examples of vault decorations in England.

Fig. 5: The beautifully decorated vaults of Ely Cathedral’s octagonal lantern space, a miracle of ancient construction and beauty.

Fig. 6: A fine example of fan vaults in Bath Abbey. Notice the beautiful heraldic shields that intermittently ornament the ceiling.

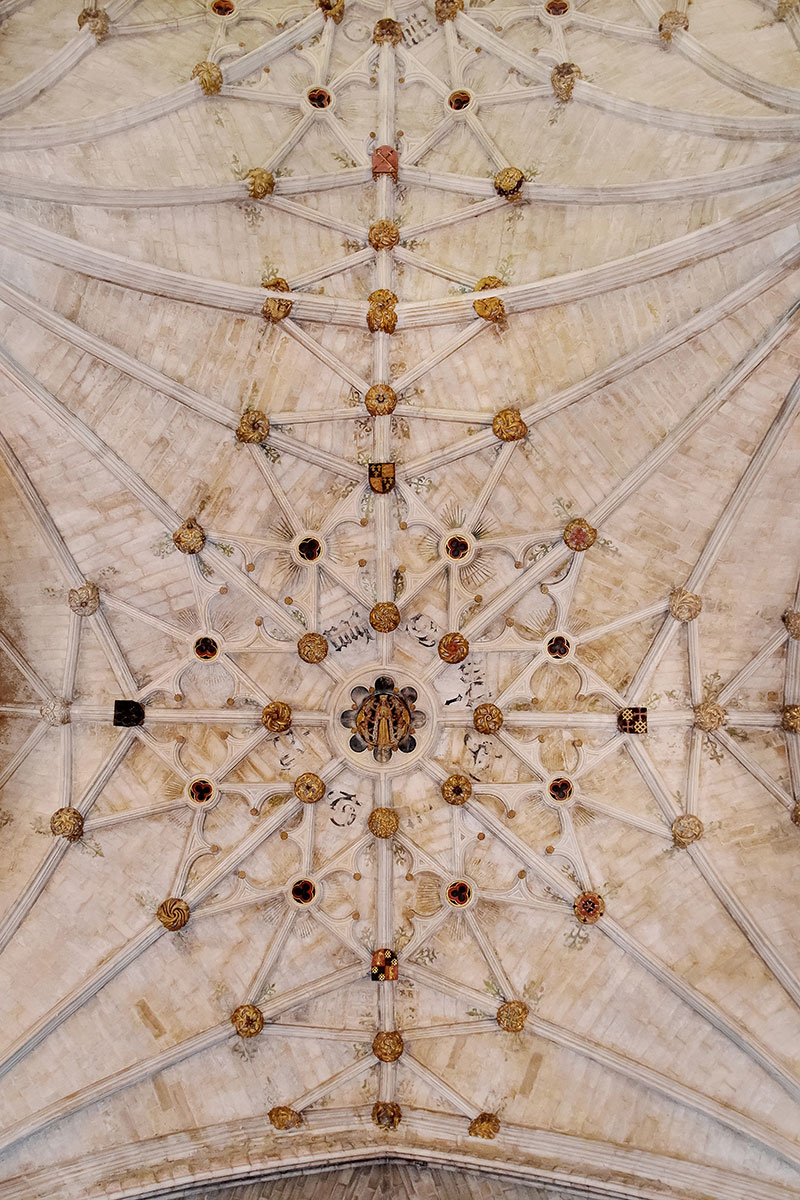

Fig. 7: Details of the decorated fan vault ceiling at Bath Abbey. Again, notice the use of shields as bosses and ornament.

Fig. 8: A closer detail of the Bath Abbey ceiling masonry and shield designs.

Fig. 9: A 17th-century decorated wooden vault under the tower. The central hole was used as access to remove and replace the cathedral bells. Notice the use of shields as bosses and ornament.

Fig. 10: Decorated ceiling of the tower of St Albans Cathedral. Refurbished in 1951-52, the shield we see are repainted by Jane Lenton. They are a copy of the 15th-century originals, which remain above them. They depict the red and white roses associated with the Houses of Lancaster and York.

Depending on where (or what era) you look, you will be pleasantly captivated by the variation of styles and types. From the quadripartite and sexpartite rib vaults, to tierceron and lierne vaults that present more decorative elements, the vaulting system of Gothic architecture brought about the freedom and opportunity to invite light into the worship space. Beyond the moderate gorgeous styles, England also boasts of some fine examples of the more complicated net, fan, and diamond vaults of the late Gothic period. Briggs (2013), in a cathedral architecture guide, describes how the masons imitated the patterns in shallow panels and how this led to incremental complexity of design, resulting in elaborate, marvelous but structurally astonishing fan vaults that can be seen at their best at Kings College Chapel, Cambridge.1

Not entirely a thing of the Gothic age, vaulting has been in use long before medieval architecture, but the development of the ribbed vault in the 12th century changed and boosted the way churches were constructed. There is no doubt, that without this technique, the architecture of the Middle Ages would have looked quite different.2 Acland (1972) argues that the first use of the rib in England came in 1096 with the construction of Durham cathedral.3

Coming much later, the fan vault is attributed to development in Gloucester between 1351 and 1377. It has been suggested that the earliest known surviving example of fan vault in England is that of the east cloister walk of Gloucester Cathedral.4 Many historians of British medieval architecture agree with this conclusion. By the end of the 12th century, the method of constructing ribbed vaults was, however, now highly developed. Lincoln Cathedral’s construction, which began in 1208 under the master mason Geoffrey de Noyer, introduced a new feature. It was called the tierceron and it was a rib system that did not follow the folding of the rib. De Noyer broke free of the strict bay system with this new sexpartite shaped vaulting formation. He was followed by another visionary architect, who separated the ribs and the vaults conceptually. Continuing the invention of the transverse rib, tiercerons connected in highly decorated bosses in the nave vault.5

The eastern transepts of the Lincoln Cathedral has the earliest high vaulting that has survived. Also worthy of note in the Lincoln Cathedral are the vaults of the St Hugh’s choir that has come to be called the ‘crazy vault’ on account of its deliberate misalignment. One author refers to it as sheer oddness of concept. Instead of converging at the center of each compartment like most vaults do, the lateral cells end at two different points, both roughly a third of the way from opposite ends of the compartment. The lopsided rhythm set up by this arrangement effectively destroys any sense of the vault as a series of distinct compartments defined by traverse ribs and corresponding bay divisions on the side walls.6

Fig. 11: The ‘Crazy Vault’ of the St Hugh’s choir, Lincoln Cathedral.

Fig. 12: Decorated ribbed vault with floral and heraldic shield bosses in Winchester Cathedral.

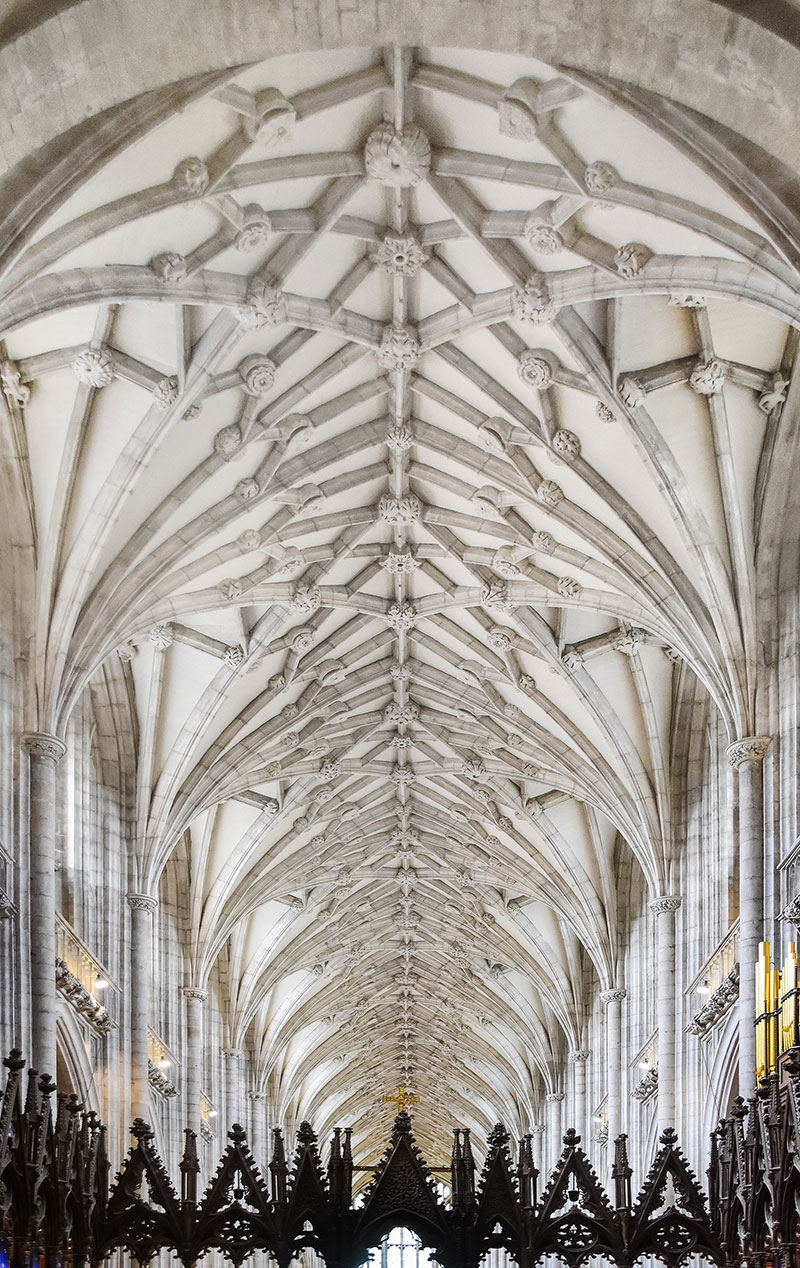

Fig. 13: The vaults of the Winchester Cathedral as seen from the quire area.

Fig. 14: A Gothic style inspired decorative chandelier in Bath Abbey.

Fig. 15: Details of vaults in Bath Abbey with heraldic shield bosses.

Fig. 16: The quire ceiling with 14th-century paintings featuring the arms of Edward III and his sons together with those of his supporters. Religious symbols are also featured.

It is not uncommon to find within the cathedrals in the United Kingdom an array of coats of arms adorning the cross points of ridges on the ceiling. In this context, they are called bosses. A boss is loosely defined as a knob or protrusion of stone or wood often found at the intersections of a ribbed vault in Gothic buildings. Dobbs (1906) argues that coats of arms or emblems have worldwide use, and are easily understandable as designed for decorative purposes, or as a means of distinguishing certain persons. The raison d'être of the emblazoned coat (from which the term "coat of arms" comes) worn by the mail-clad warriors of the Middle Ages, helped that the warriors be recognisable to friend and foe alike.7

While the bosses may come in floral, animal or other figural forms, it will appear that the heraldic shields are also quite favoured as it may suggest a link with important and sometimes regal personas of the area. The presence of heraldic shields may also tell of the patronage received by the cathedral from the family or bearers of the arms. Heraldry is found to be most intimately associated with the Gothic architecture of England, and happy it was for the early heralds that in their day the English Gothic movement was at work in its full strength. The alliance between heraldry and Gothic architecture in England was never interrupted or permitted to decline from its original forte. So as Gothic flourished, heraldry held its own place in architecture. And in the finest works that exist in Great Britain, heraldry is ever present to adorn the cathedrals in almost every position in which such ornamentation could be admissible. Thus, in England, early heraldry is found to have been the fellow-worker with the early Gothic architect.8

Quite reasonable again is Dobb’s argument as one will often find heraldic shields of arms to be of considerable number in several cathedrals. If one was attentive to the ornamentation language particularly in Perpendicular style Gothic churches, you will see shields whereas you turn. You will find them in stained glass windows, engraved on pews, gables, doors, on floor tiles, placed as stand-alone or held by grotesque creatures or sometimes even saints and of course as bosses on vaulted ceilings. There is to be no doubt of the prominence of heraldry in Gothic cathedral ornamentation in the United Kingdom.

I mentioned in an earlier post that ornaments add value. As I continue to travel through Europe, I see this to be a truism. We all seem to follows this very simple philosophy. It appears to be an innate impulse for us to decorate a thing that has value to us or that we wish to add value to. Even in our very postmodern world, a little decoration here and there is not lacking.

Fig. 17: Detail of floral boss design in Salisbury Cathedral.

Fig. 18: Close up details of part of the fan vaults of Bath Abbey showing the arms of the Pre-reformation Priory.

Fig. 19: Close up details of part of the fan vaults of Bath Abbey showing a shield as part of the ceiling vault design.

Fig. 20: Colourfully decorated vaults of the Langton Chapel inside the Winchester Cathedral. Notice the floral and arms shield bosses.

Fig. 21: A cherub holding an arms shield on a heavily ornate ceiling in Winchester Cathedral.

Fig. 22: A mitre resting upon arms beneath one of the mortuary chests containing the bones of Saxon kings in the quire area of Winchester Cathedral.

Fig. 23: A cherub holding a shield of arms atop a column capital. Winchester Cathedral.

Fig. 24: A heraldic coat of arms flies inside the northern Isle of the Winchester Cathedral.

Fig. 25: Richly ornate choir stalls of Salisbury Cathedral famed to be the largest complete set in Britain. The rear stalls feature shields.

Fig. 26: Arms of Henry VII on the west front beneath the statue of the monarch overlooking the west door entrance. Henry was monarch at the time of Bath Abbey’s beginnings.

Fig. 27: Another example of a shield as ornament on the ceiling of Bath Abbey.

Fig. 28: Close up ornate details of the ceiling vaults of Bath Abbey.

Fig. 29: Fan vaults in Winchester Cathedral.

A Short Note on Salisbury

The cathedral at Salisbury is one for the books. Unlike the cathedrals in France, many of the British churches situated away from London still have quite an enviable parcel of land around them. In this list of well landed cathedrals, Salisbury is indeed to be respected. The church also has an impressive spire placed on top of the tower at the transept crossing. The spire towers at 404 feet (123m), making it the tallest in Britain, and a most glorious piece it is. Little wonder the parishioners of the Cathedral Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary (the official name of the Salisbury Cathedral) boast that the spire can be seen from wherever in Salisbury.

Now to the name Salisbury; pronounced as ‘Sols-bry’. I couldn’t get past this one. Yes, I am no English scholar but I’ll often ask the question, why is a letter part of a word when you have no intention of using it? The people of Salisbury say ‘Sols-bry’ totally ignoring the ‘lis’ part of the pronunciation. Frankly, I was more inclined to saying ‘Sa-lis-bry’ and this, you will imagine, got quite a stare. At one instance, I had the opportunity to discuss this with a gentleman. Even he, being British, had no idea why it is Sols-bry instead of ‘Sa-lis-bry’. We both got a good laugh out of it though. Same is to be said of the folks at Canterbury. They pronounce it as ‘Can-ta-berry’ and I insisted on the version ‘Can-ta-bry’—this, in spite of the popularity of the ‘Can-ta-berry’ version and of course the town being theirs, not mine. A priest at the cathedral who was so kind to speak with me on many issues including this one said he is not a native of Canterbury and he sees my point but the fact is ‘Can-ta-berry’ is the way the word has been pronounced for years and he bets it will continue to be that way and, just as in Salisbury, we both had a good laugh at the whole thing.

Fig. 30: The spire of Salisbury Cathedral at 123 m is said to be the tallest in Britain.

Fig. 31: Salisbury Cathedral from the northern end.

Fig. 32: The western façade of the Salisbury Cathedral. The façade features over 80 statues of apostles, disciples, saints, martyrs, royals and other biblical figures.

Fig. 33: A view of Salisbury Cathedral altar from the quire.

Fig. 34: Ornate wall décor inside Salisbury Cathedral.

Fig. 35: A sculptural monument in honour of Thomas Gorges who built the Longford Castle. Gorges died in 1610. Behind is a stained glass window by Christopher Webb.

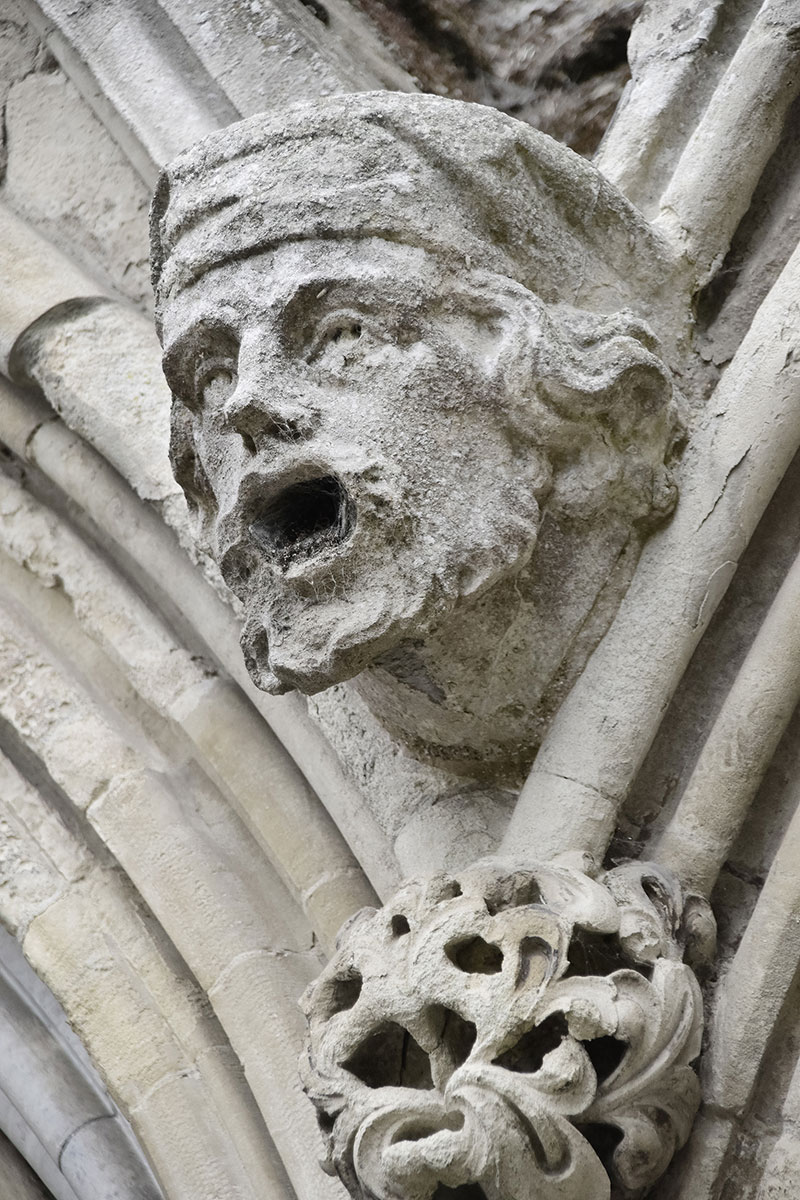

Fig. 36: Gargoyle in the shape of a human head on Salisbury Cathedral west front.

Fig. 37: Gargoyle in the shape of a ‘green man’ on Salisbury Cathedral west front.

The current Salisbury Cathedral was consecrated in 1258, though the foundation stones were laid 38 years earlier. There had been an earlier cathedral built on the chalk hill at Old Sarum two miles away from where the current one stands.9 The building work of the new cathedral was supervised by master mason Nicholas of Ely and the Gothic details of the cathedral are thought to have been the responsibility of Canon Elias of Dereham, a clergy man with a vast amount of architectural knowledge. Another recognition to his honour is that he was titled ‘The Most Honest Man in England’—but that is a story for another day.

Towards the western end of the 200-foot-long nave is a brilliantly designed contemporary font known as the Living Water Font, designed by British sculptor William Pye. The font was installed in the cathedral nave in 2008 as part of the 750th anniversary celebration of the consecration of the cathedral.10 Water from the four angled pieces flows continuously through slots at the four corners and disappears into the ground (as it were) through gratings in the floor.

The cloister of this cathedral is a beautiful space. The cathedral's octagonal Chapter House is accessed through the cloisters walk. The cloister boasts of original 13th-century beautifully carved ceiling bosses with some of the original paints still visible. The Chapter House itself is a masterpiece. With a similar design to that of Westminster Abbey, it features an elegant fan vault ceiling that rises from a single central column. Stone benches are seen at the walls forming a circle around the central column. These is where the chapter members sit to discuss business.

Fig. 38: A view of the Living Water Font facing the west end of Salisbury Cathedral.

Fig. 39: A view of the nave facing the east end of the Salisbury Cathedral. The columns and arches are reflected on the water from the Living Water Font.

Fig. 40: A statue of Canon Elias of Dereham in Salisbury Cathedral. On the base of the statue, the text notes that the statue was given to Salisbury by the freemasons.

Fig. 41: The pedestal of the statue of Canon Elias of Dereham inside Salisbury Cathedral. Notice the symbol of the freemasons affixed.

Fig. 42: Statue of Bishop Poore at the west front of Salisbury Cathedral. Poore was made Bishop of Salisbury in 1217 and is credited to have moved the cathedral away from its former location in the old Sarum to its present location on permission of the pope.

Fig. 43: The cloister garth with two cedars of Lebanon trees planted in honour of Queen Victoria's accession to the throne in 1837.

Fig. 44: Another view of the cloister garth of Salisbury Cathedral with the pinnacles of the west front visible in the background.

Fig. 45: Part of the cloister of Salisbury Cathedral.

Fig. 46: Part of the cloister of Salisbury Cathedral. The two cedars of Lebanon can be seen through the gaps.

Fig. 47: Part of the cloister of Salisbury Cathedral with rib vaults and an interesting head piece being exhibited by local artist.

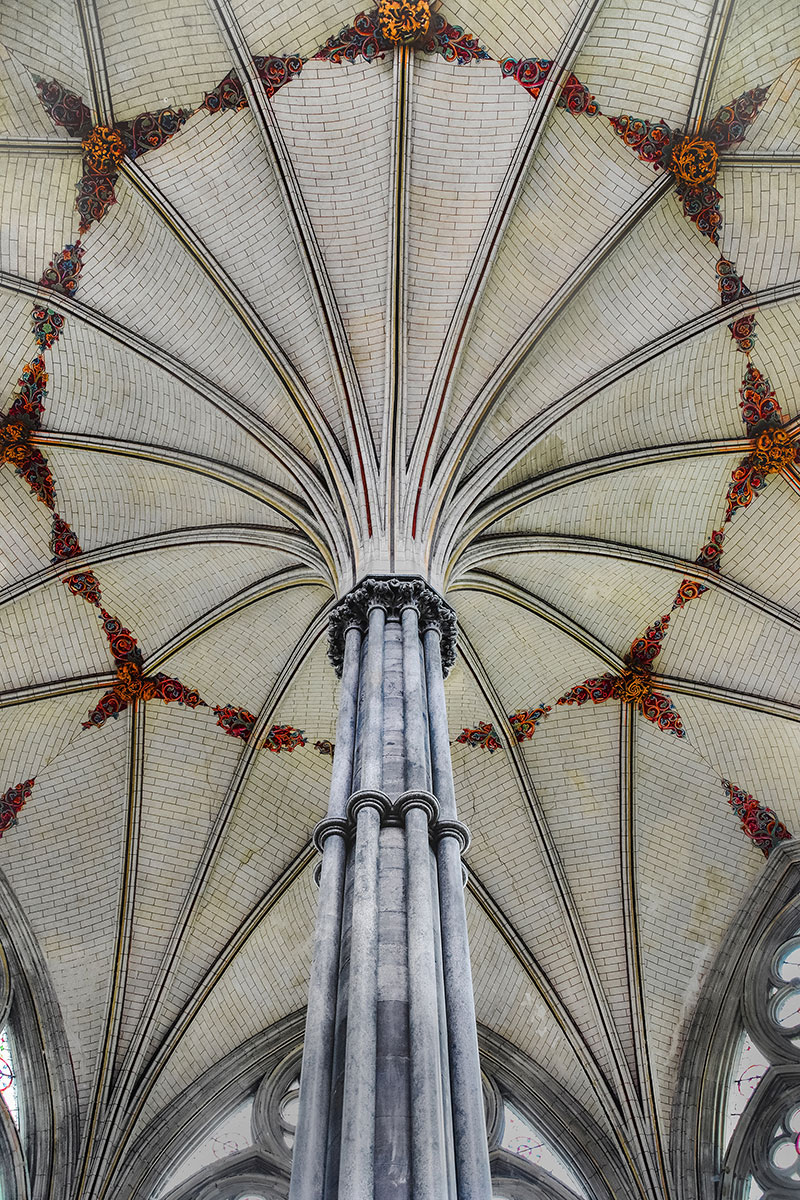

Fig. 48: Part of the Chapter House of Salisbury Cathedral showing stained glass windows and the central column from which the impressive fan vaults fan out.

Fig. 49: The single and central column of the Chapter House of Salisbury Cathedral transitioning into fan vault ceiling.

Fig. 50: A view of part of the nave looking towards the west end of Salisbury Cathedral.

2 Dalicsek Daniel, “The Importance of the Ribbed Vault in Gothic Architecture,” accessed October 20, 2017.

3 James H. Acland, Medieval Structure: The Gothic Vault, (Toronto: University of Toronto press, 1972), 83

6 Wilson, “The Early English Style,” accessed October 22, 2017.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top