-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

The Basilica of St Peter: No Words to Describe

'Deyemi Akande is the 2016 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

Besides a final report, this is officially the last article of my H. Allen Brooks fellowship year. Understandably, it comes with a cocktail of emotions. I had mentioned in the last article that I will write on my experience at the Vatican this month, but alas, here I am now at a loss for words to express the experience. Suffice to say that the Vatican numbs me in every beautiful way. For over three hours I paced here and there in the nave of the St Peter’s Basilica, voraciously feeding my eyes and mind with the intense visual array of ornaments, symbols, and patterns. Interestingly, in the end, I could not help the feeling of inadequacy. The feeling that I still do not know enough; that I remain significantly deficit in knowledge in spite of my best efforts. Every material I come across has something new to add to the Basilica’s history. The Basilica is one of those buildings you want to be able to talk about confidently rolling out dates from your head like an encyclopedia, but no matter how much I read, it felt insufficient and I, desperate. I am at once reminded of the fine letters of the Holy Book and forced to console myself therewith. It admonishes in its book of Ecclesiastes 12:12 “Be warned, my son … of making many books there is no end, and much study wearies the body.” I blatantly saw the rationality of this in my quest for comprehensive knowledge of the Basilica Papale di San Pietro.

If I had just a day to see Rome, by all means I would spend three quarters of it at the Vatican, particularly at St Peter’s Basilica. I am not a Catholic, but I have a lot of devote Catholic friends and students. Perhaps in reverence to their conviction and in my uncontrollable respect and love for Church history, I would consider it a great error on my part not to have given ample time to St Peter’s Basilica during my visit. Of all its history and controversies, it continues to carry a type of transforming power and unseen force like no other space. The site and structures of the Vatican, however concrete and marble they are, will feed your soul in a manner that ignites an inner wonder; the type of wonder I have spoken about several times; the one that turns a history-loving person into a suckling. The words of John Varriano comes to mind. He declares there is scarcely an account of any Roman sojourn that does not contain the impressions of a visit to St Peter's. Those who remained silent about virtually everything else often found their voices inside the great basilica.1

Fig. 1: An evening view of the Basilica Papale di San Pietro (St Peter’s Basilica) from the St Peter’s square in Rome.

Fig. 2: As old and as true as the sky. St Peter’s Basilica, portrayed by Viviano Codazzi in a 1630 painting. Most of the main features including the obelisk at the centre of the piazza remain the same today.

Fig. 3: An evening view of St Peter’s Bernini's colonnade and to the left hand is the Maderno's fountain

Fig. 4: The obelisk in the centre of St Peter’s Piazza. Standing 83 feet tall and moved to the current position by Domenico Fontana in 1586 on the order of Popes Sixtus V.

Fig. 5: Close up of St Peter’s Basilica dome, redesigned and completed by Giacomo della Porta in 1590. In the foreground are statues of Christ the redeemer (to the right with the big cross) and St John the Baptist with the green patina slim cross. St James the elder barely shows to the far left.

Fig. 6: The Loggia of the Blessings—Close up of the Papal balcony of St Peter’s Basilica—from here a new pope is announced and on this balcony he gives the Urbi et Orbi blessings. Also, the pope addresses the people gathered on special occasions from this balcony.

Fig. 7: A gull quenches its thirst from the ‘living’ waters of the Maderno's fountain on the grounds of St Peter’s Piazza.

Fig. 8: Papal Coat of Arms.

Fig. 9: Coat of Arms of Pope ALEXANDRA VII.

Fig. 10: A concoction of patterns, figures and symbols mostly of gold and blue and the natural shades of concrete too. Such wonderful beauty to behold. The space around the main altar inside St Peter’s Basilica.

St Peter’s Basilica is deemed to be one of the Holiest sites in all of the world by many Christians and the principal church of one of the most powerful men on earth – the Pope. So I must be pardoned for my ‘sin’ of touching material objects of historical significance. It is a thing I do every time I find myself in a place or with an object of reverence; I do it to connect with the past and I must confess it gives me a heighten sense of delight. It is my way of affirmation that I came in contact with the past. At the Vatican, this my indulgence was in overdrive. When it was possible, I touched almost anything that had a sense of age and importance. To me, it is like touching the very hand of Michelangelo or Bernini.

I am one of those who fantasise about touching something old and suddenly get transported to an unknown past – very much like the experience of the character Claire Frazer (played by Caitriona Balfe) in the TV serial Outlander where she touched an ancient enchanted rock and was sucked into a different time in the past. However, as magical as this experience may be, and perhaps as fruitful as it may appear for a historian, I imagine finding one’s way back to their rightful time may prove something of a difficult task. In light of this, I have resolved in my heart to stay in the present and look to the future instead.

In the Vatican, not minding much for being warped into another time, I bent over barricades to get closer access when possible and I remember trying to reach the statue of St Peter mounted on a pedestal of 4 meters to the left side of the basilica’s front façade. The statue itself was about 17 feet tall, and one can imagine how clumsy it was to reach the feet atop the pedestal. I fell short of the feet of the Apostle, but reached the papal crest of Pius IX. In the bitter cold, my skin touching the stone was indeed a warm feeling. In my mind, I felt transported to the late 1849 when the brilliant stonecutters, Angelo Bezzi, Fortunato Martinori, and Vincenzo Biancheri completed the tall pedestals and decorating them with the heraldic emblems of Pope Pius IX. In my last article, when I spoke of the mesmerising feeling I had at the Vatican, it is to such experience I refer to; the type that I now betray its depth with my shallow and hasty words.

Probably the height of my mesmerisation inside the Basilica was when I came eye to eye with the grieving mother of Christ in the beautiful work by Michelangelo: the Pietà. Time literally froze. I had seen several photographs of it in books and read countless articles but here I was only about 10 ft away from the master of masterpieces. It remains an indescribable experience. This is what St Peter’s Basilica will do to even the most restrained of beings, it reaches deep into your place of concealed emotion and brings out a measure of reality in you. I must have said ‘wow’ a hundred times in the twenty-two minutes or so I spent staring and not yielding to the light jostling by the crowd around me. Robert Kahn puts it this way, St Peter's is a resume of so much that is Roman, from Michelangelo's Pietà to Bernini's Baldachin and Cathedra Petri and Giotto's mosaic of the Navicella. Its outsized dimensions and grandiose decoration are overwhelming, making the experience of walking through the building a dynamic one.2 I couldn’t agree more.

Fig. 11: Maderno’s nave of the St Peter’s Basilica looking towards the chancel. No space is left to waste – every spot available is ornamented or dressed by mosaic art or sculpture.

Fig. 12: The papal crest in marble on the floor of the nave inside St Peter’s Basilica.

Fig. 13: At the main altar of St Peter’s Basilica looking up into the inner portion of the baldachin. The 98-foot-tall baldachin is an elaborate ornamental canopy held by four immense twisted pillars all designed by Bernini between 1624 and 1632.

Fig. 14: One of the four pedestals of the baldachin, made of fine polished wood with a brilliantly gilded ornamental plaque.

Fig. 15: The dome of St Peter’s Basilica from the nave. Along the base of the inside of the dome is written (translation from Latin), in letters about six feet high each, from Matthew 16:18-19; "...you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church. ... I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven...." Near the top of the dome is another, smaller, circular inscription: "To the glory of St. Peter; Sixtus V, pope, in the year 1590 and the fifth year of his pontificate."

Fig. 16: The 17-ft-tall statue of St. Peter in front left side of the Basilica, commissioned Giuseppe De Fabris by Pius IX (1846–1878).

Fig. 17: Michelangelo's interpretation of the Pietà (1498–1499), one of the most emotive of the artist’s work. It is tough to get a good shot of the sculptural piece as it is (probably deliberately) placed in a low light space on the northern part of the Basilica. A glass wall protects the pieces making it even more difficult to photograph due to reflections.

Fig. 18: A statue of St Andrew inside St Peter’s with what has now come to be called the St Andrew’s cross. The piece is by Francois Duquesnoy.

Fig. 19: A statue of St Veronica inside St Peter’s holding her veil with the face of Jesus on it. The piece is by Francesco Mochi.

Fig. 20: Statue of Pope Pius X inside St. Peter's Basilica.

Like many great church buildings, there was an old church on the same site before the ‘new’ and current one. St Peter’s Basilica is no different. The old church on the same site was a simple basilica commissioned by Constantine the Great after he converted to Christianity. The building of the old church itself was a replacement for an older sanctuary begun around the year 323. The current edifice, however, replaced the Constantine basilica in the year 1506 though it was not completed until over a hundred years later in 1626. The site where St Peter’s Basilica is built, is believed to be over the very place where Simon Peter, apostle of Jesus, first bishop of Antioch and later first bishop of Rome was buried. Clearly the scriptural rhetoric for the inspiration of the basilica on that spot will be the verse from the book of Matthew “… on this rock, I will build my church and the gates of hell will not prevail over it…”3 this is however not expressly stated. The burial spot of the apostle Peter is said to be directly underneath the massive basilica’s baldachin.

Directly in front of the basilica is the St Peter’s square – Piazza di san Pietro. This square has racked up quite a reputation and is now as famous as the basilica itself. Designed and built by Gianlorenzo Bernini between 1656 and 1667, the square is flanked by two elliptical colonnaded corridors with twin columns of the Doric order lining the whole length. A significant feature of the square is the array of over one hundred 10-ft-tall statues of saints along the roof of the elliptical colonnaded corridor.

Fig. 21: The main façade of St Peter’s Basilica, Rome.

Fig. 22: Statue of St Albert Avogadro – Carmelite on top the elliptical colonnaded corridor of St Peter’s Basilica. St. Albert was born 1149 and died 14 September 1214. This piece was sculpted by Lazzaro Morelli c.1667–1668. St Albert was Patriarch of Jerusalem, and wrote the original Carmelite Rule of St Albert around 1210.4

Fig. 23: Statue of St. Clare of Assisi on top the elliptical colonnaded corridor of St Peter’s Basilica. St Clare was born 16 July 1194 and died 11 August 1253. The piece was sculpted by Lazzaro Morelli c.1667–1668. Clare was one of the first followers of St Francis of Assisi. She is shown dressed in the habit of the Order of Poor Clares, which she founded. The saint holds a monstrance that alludes to a story that her convent was attacked by marauders, and that she put them to flight by showing them the Blessed Sacrament.5

Fig. 24: Statue of St. Remigius on top the elliptical colonnaded corridor of St Peter’s Basilica. The Bishop was born ca. 437 and he died ca. 530. This sculpture was created ca.1668 and installed between 29 May and 3 July of 1668 by Giovanni Maria de Rossi. Bishop Remigius was Bishop of Reims, he baptised Clovis I, King of the Franks, leading to the conversion of the entire Frankish people. His image is particularly numerous in France and Germany.6

Fig. 25: Statue of St. Dominic on top the elliptical colonnaded corridor of St Peter’s Basilica. St Dominic was born in 1170 and died on the 6th of August 1221. This statue was made installed at the Basilica in 1668 by Lazzaro Morelli, Bernini’s assistant. St Dominic wears the habit of the Dominican order, which he founded, with scapular and hood and a tonsure on his head. In his left hand he holds a lily. His foot rests on a closed book, which can be symbolic of a heretical work, as a major impetus in founding the Dominicans was to fight heresy. The spread of the Rosary is attributed to St Dominic.7

Fig. 26: A shadow of the author is cast over one of the sixteen wind roses floor markers on the St Peter’s square. The wind Rose surrounds the obelisk in the Square and are aligned with compass points to show wind directions.

Fig. 27: The massive twin colonnaded elliptical corridor of the St Peter’s Basilica.

Fig. 28: An enormous marble bowl in the centre of the Pio-Clementino museum surrounded by brilliant life-sized renaissance sculptures inside the Vatican. An example of the exquisite art that one finds in the Vatican. The Vatican museum holds over 50,000 art pieces and about 20, 000 are on display at any given moment.

Fig. 29: A frescoed wall inside the Vatican Museum.

Fig. 30: A slightly larger-than-life-sized marble statue of the Nile inside the Vatican Museum.

Fig. 31: Ornamented roof work with an oculus, which concentrates light on the Nile statue inside the Vatican Museum.

Milan Duomo

With almost 600 years of history, the Duomo di Milano is arguably the most impressive building in the whole of Milan. The church is dedicated to St Mary of the Nativity and is the seat of the Archbishop of Milan. The cathedral is one of the biggest pre-19th-century churches ever built, it is outdone only by a few great cathedrals like Seville Cathedral in Spain, Basilica of Our Lady of Aparecida in Brazil, and St Peter’s Basilica in Rome. One thing the Duomo di Milano has that is yet to be contested by any other church is the number of sculpture on the edifice. Duomo di Milano is famed to have the largest number of sculptural elements on it; it features over 3,300 statues. Milan Cathedral stands as the most sculpturally ornamented gothic building in the world. Thankfully, quite a lot is known about the creation process of many of these wonderful sculptures on the cathedral due to rigorous documentation.8 Probably the most famous sculpture of all the cathedral’s pieces is that of St Bartholomew. Designed and create by Marco d’Agrate in 1562, the sculpture presents the prophet with his flayed skin hanging over his body. The neo-naturalistic finish of the piece will do a number on the faint hearted. The artist presents the anatomy of the figure in very raw and convincing details—a brilliant visual representation of the reality of early Christianity.

Many archaeologists believe that the location of the Duomo was a sacred Roman site for centuries before the arrival of Christianity. The first Catholic cathedral in that spot was known as Santa Tecla, built around 355 CE. The ruins of its baptistery can still be seen underneath the Duomo. A second basilica was later built next to Santa Tecla, called Santa Maria Maggiore. For nearly a thousand years, these two cathedrals performed; however, by the 14th century, fire and age had taken a huge toll on them. In 1386, the Archbishop of Milan, Antonio da Saluzzo, announced that Milan would build a new cathedral to replace Santa Tecla and Santa Maria Maggiore.9

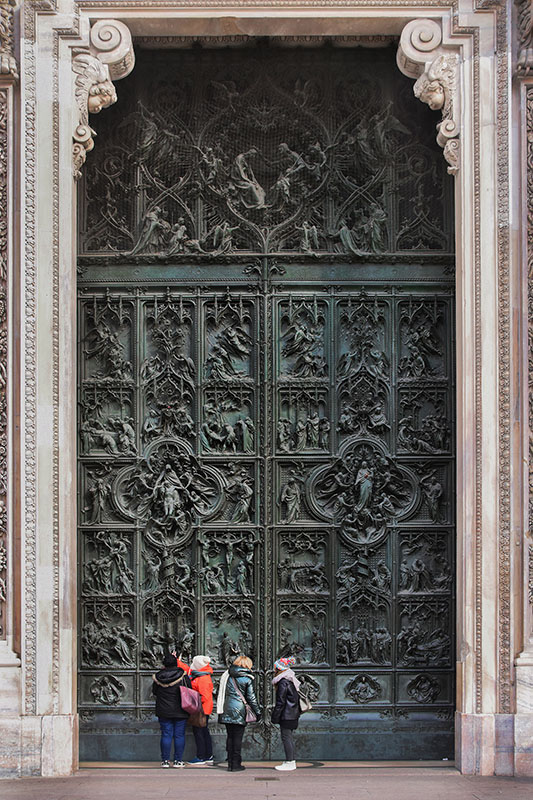

The Laying of the new cathedral’s first stone was in 1386 and work effectively finished only in 1965 when the last gate of the cathedral was inaugurated and, while this year is officially deemed to be the year of completion, maintenance and partial construction still continues until date. Surprisingly, it was Napoleon who ordered the final completion phase of the work on the Milan cathedral in 1805, leading to the months that he (Napoleon) was to be crowned king of Italy. At one point, the statue of Napoleon was placed on one of the 135 cathedral spires as a sign of gratitude to his commitment to finishing the cathedral. From the late 1820s to 1850s major finishing was done on the cathedral. The central and oldest of the cathedral’s five bronze doors facing the Piazza Duomo was already in place and is simply a marvel. It is the largest of the pack and frankly, I find it tough to wrap my head around the artistry and detailed craftsmanship put into the piece by its designer Ludovico Pogliaghi. For something that was done in the nineteenth century, the virtuosity and delivery is very commendable.

Fig. 32: The main façade of the Duomo di Milano. In the foreground is the Duomo Piazza.

Fig. 33: Details of the upper part of the front façade of Milan Cathedral. To the top, one will get a hint of the famous Madonnina, the statue of Mary that stands on the cathedral’s highest spire.

Fig. 34: The southern façade of the Duomo di Milano showing several sculptural ornamentation attached to the surface of the building at different levels.

Fig. 35: An interesting marble piece on the southern wall of Milan cathedral. It is of a man with a shovel carrying the remains of another.

Fig. 36: One of the several sculptural pieces on the southern wall of the Milan Cathedral.

Fig. 37: The 1562 emotive sculpture of St Bartholomew with his flayed skin hanging over his body like a cloak at the Milan Cathedral.

Fig. 38: A most outstanding piece of art! The central door of Milan Cathedral’s western wing. The Ludovico Pogliaghi bronze work stands at over 30 ft tall and heavily ornamented with embossed sculpture of a naturalistic nature.

Fig. 39: Details of the ornamented trimmings on both sides of the door.

Fig. 40: Closer details of the marble trimmings around the central door of the western wing at Milan Cathedral.

Fig. 41: Closer details of the marble trimmings around the central door of the western wing at Milan Cathedral.

Fig. 42: Details of Ludovico Pogliaghi’s Pieta on the central bronze door of the western wing at Milan Cathedral.

Fig. 43: Details on the central bronze door of the western wing at Milan Cathedral.

Fig. 44: Pinnacle statues of Milan Cathedral.

Fig. 45: A view of part of the shopping Plaza near Milan Cathedral from the Piazza del Duomo.

LET ME STOP IT WHERE IT ALL STARTED: EGYPT.

My journey to see ornamentation on temples firsthand started twelve months ago, and I am now at the very end of the road. It only makes sense to see the oldest forms of such expressions and nowhere else will I turn but to Egypt – possibly the oldest examples of ornamentation on architecture by man known to the modern world.

Because of time and logistic constraints, my trip to Egypt was rather short but fruitful. I decided to see the Karnak Temple Complex. The UNESCO World Heritage site is famed to be the second most-visited site in the whole of Egypt, second only to the pyramids of Giza. For this site, I prepared myself to encounter the ruins of an ancient heritage as I saw in Greece, and while I did not expect to see much by way of structures, I can frankly say that my expectations were surpassed. The ruins at Karnak, though far less taken care of and of course far older, were as majestic as those of Greece in spite of the age over it. These structures are dated to the Middle Kingdom Era of Egypt, which is about 2055–1650 BC. That is about 4,000 years ago! Most of the columns still stand. Several obelisks were still gloriously pointing to the sky. As I stare at a physical articulation of age still standing relentlessly, almost immortal, I am taken over by awe. Millions have stood where I now stand, royals and simpletons, natives and invading foreigners. These walls are witness to time in a way that no history can recall. The temples are quite impressive and audacious and besides the hushed murmurs of the tourists, there is a type of stillness over the space. At every light wind, the eastern dust rises and with it rises one’s sense of pride and glory. These temples are as old and true as the skies, they have been the sky lines of this ancient city since the mind can recall.

The temple area was used by several Pharaohs each adding his own extension and complexity to the system. Walking in the hypostyle hall, all the way to what would have been the naos (the place of the innermost alter) back then is indeed a privileged and humbling feeling. The hieroglyphs on the surface of the columns and walls are a testament to the age of the structures. I made no attempt at interpreting the hieroglyphs (not that I could on the go, but luckily one can make some sense out of the images if you land on the right google pages); needless to say the pictograms were telling. We owe the resurrection of this form of documentation in Egypt partly to a misfortune of an invasion by the French under the leadership of Napoleon and to the finding of what has come to be called the Rosetta stone. Through the tireless work of two brilliant minds: Frenchman Jean François Champollion and Englishman Thomas Young; many Egyptologists were reinitiated into the wisdom of old through the understanding and reading of the ancient pictograms. I am no Egyptologist but in Karnak, I was proud of what I saw.

Fig. 46: The approaching the hypostyle hall with worn down pylons at the Karnak Temple.

Fig. 47: A Pharaoh’s statue amongst ‘hieroglyphed’ columns at the temple complex in Luxor.

Fig. 48: Giant seated figure of the Pharaoh believed to be Ramses II at the Karnak Temple in Luxor.

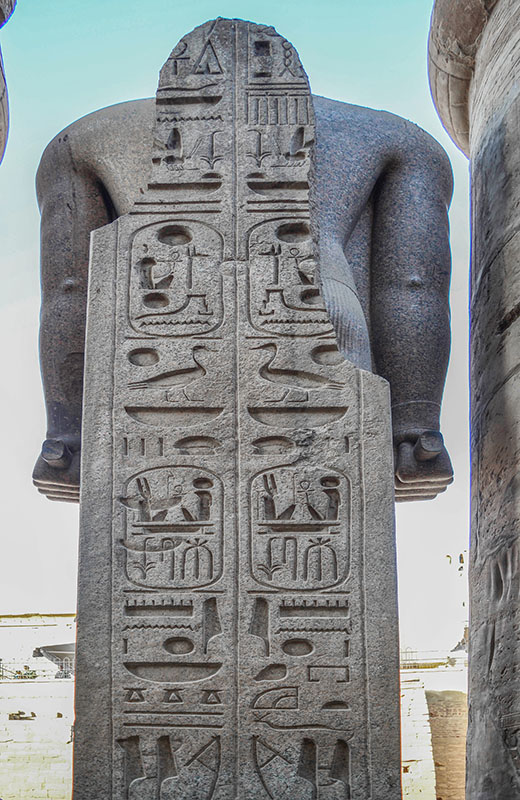

Fig. 49: The reverse side of the Pharaoh’s statue laid with hieroglyphs.

Fig. 50: Details of hieroglyphs on a column in Karnak temple. These ‘texts’ are laid out in bands of about a meter in height. The hieroglyphic pictograms are finely done and rather precise in height and arrangement.

Fig. 51: Pigment coloured hieroglyphs on a crossing beam. It is not uncommon to find the complete walls and ceiling of spaces covered with hieroglyphs either painted in or incised.

Fig. 52: The Great Hypostyle hall with towering columns reaching the height reaching 70 ft (about 21 m) and 3 meters in diameter.

Fig. 53: Details of hieroglyphs on one of the obelisks at the temple complex.

Fig. 54: Details of hieroglyphs on the walls of the Karnak Temple.

Fig. 55: A row of columns in the Karnak Temple complex.

Fig. 56: The dead grounds come alive at night with night lights and modern events shows.

2 Robert Kahn, Angela Hederman, Pablo Conrad, City Secrets: Rome, (New York: The Little Bookroom, 1999), 79

8 Irving Lavin, Visible Spirit: The Art of Gianlorenzo Bernini, (London: The Pindar Press, 2007), 35–36

9 Christopher Muscato, “Milan Cathedral: History & Facts,” accessed March 15, 2018. https://study.com/academy/lesson/milan-cathedral-history-facts.html

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top