-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Rjukan, Reflected: Twelve Short Essays on a Year of Global Industrial Heritage

Sarah Rovang is the 2017 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

Encountering Rjukan, Norway

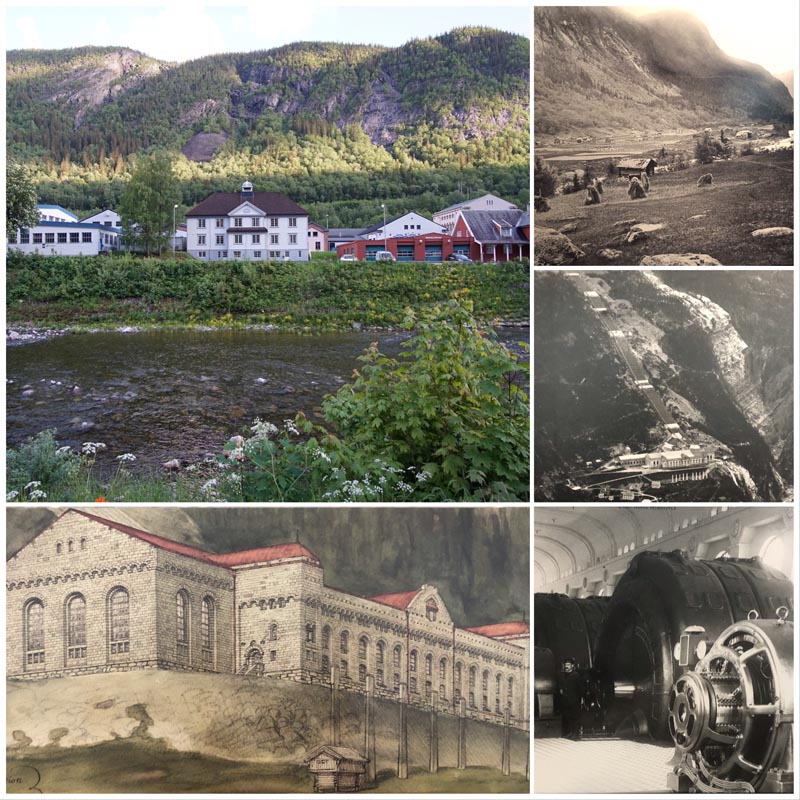

Clockwise from upper left: Photo by the author of central Rjukan; Vestfjord Valley looking towards Såheim, 1907 (NIWM); Vemork power and reserve station 1920 (Norsk Hydro); Vemork station interior (Norsk Hydro); Perspective of Vemork Power station (NTNU archives). All reproduced archival material is from the Norwegian Industrial Workers Museum (abbreviated NIWM) unless otherwise noted. Where NIWM’s source material was credited, I have noted it in the captions as above.

It has been a while since I road tripped with my parents, probably since high school. And there was part of me that felt eighteen again, in the front seat of a rented hybrid, juggling navigation and climate control. But instead of the familiar I-25 corridor between New Mexico and Colorado, we were plunging into the hinterlands of southern Norway, watching the towns get smaller and smaller while the fjords grew deeper and deeper.

During the last weeks of my H. Allen Brooks Fellowship year, my parents joined me for my final industrial excursions in England, Norway, and France. Since retiring, my father has immersed himself in genealogical research, proving that a proclivity for stubborn, protracted archival research is indeed a heritable trait. He recently pinpointed the origins of his mother’s family near Rollag, Norway—a town conveniently close to Rjukan, a UNESCO site that has been on my Brooks itinerary since the very first draft.

After a stop for architectural history and apple cake at Norway’s largest stave church, it was on to the Telemark region. We rolled into Rjukan around the same time as the clouds. Rjukan is situated in the steep, narrow Vestfjord Valley a few hours northeast of Oslo, and when blanketed by clouds the whole town feels a bit claustrophobic. During the winter, portions of the valley go for months at a stretch without sunlight. Before my visit, I thought the town’s recent decision to construct three massive mirrors reflecting sunlight down into the central square was a clever novelty; a bit of Atlas Obscura-bait for lovers of odd places like me. I left thoroughly convinced of its utility.

Rjukan is perhaps best known as the site of some top-notch World War II intrigue: the factory town where cunning Norwegian saboteurs working in concert with British intelligence thwarted Germany’s production of heavy water as part of that country’s unsuccessful atomic research program.1 More recently, Rjukan served as a film set for a highly-regarded 2015 television miniseries based on these historic events. The filming provided an impetus for the town to rebuild or restore a number of the historically-significant industrial buildings in the valley. When the clouds cleared and I set out on foot to explore Rjukan’s eastern reaches in the interminable Norwegian summer twilight, portions of the town took on the glittering unreality of a stage set. I had binge-watched The Heavy Water War in a hotel room a few weeks before, and now everything felt vaguely familiar, though decidedly less covered in snow. There was the “Director’s House” right up on the hill, and over there, the courtyard where the Norwegian infiltration team snuck in to destroy the heavy water reserves.

The reason that there was heavy water in Rjukan in the first place, and hence all the Nazis and the sabotage and the subsequent film crews, derives from the town’s singular industrial history. Compared to other European nations, Norway industrialized late and rapidly—practically skipping the first industrial revolution (that of coal and steam) and jumping in only at the second (that of electricity, specifically hydropower, and chemical engineering). The river valley landscape encompassing Rjukan and the nearby community of Notodden was the site of Norsk Hydro’s unprecedented investment in hydropower, massive chemical plants, rail transportation, and worker housing.2 Vemork, a revolutionary plant at Rjukan, manufactured nitrate fertilizer by pulling nitrogen out of the air, and also produced heavy water as a byproduct. The compounded layers of technological innovation, architectural expression, and WWII history all contributed to the inscription of the Rjukan-Notodden landscape on the UNESCO World Heritage list in 2015.

That night when I wandered the banks of the Måna River with my camera, relishing the long, languorous golden hour, it occurred to me that I was not just witnessing Rjukan; this particular accretion of industry, town planning, and public history. Instead, I was perceiving a rich composite of related sites; memories accrued over a year’s worth of travel. For my last official SAH blog post, I wanted to do something a bit different from the longer narrative blogs I’ve been writing throughout the year. What follows is a StoryMap, created with a free digital storytelling tool published by KnightLab. This StoryMap reinterprets the architectural and cultural landscape of Rjukan through a series of comparisons with an admittedly small portion of the diverse sites I’ve visited over the past year. Some of these intentionally experimental and speculative juxtapositions ultimately revealed aspects of architecture, culture, and landscape that I hadn’t considered about either site in isolation. What ties each of these comparisons together is the recurrent tension they reveal in nineteenth- and twentieth-century industrial sites between global trends and local forces, the international and the idiosyncratic.

Below, you can click to enter the embedded StoryMap, or see the same text and images in a more standard blog format further down.

Humberstone: Nitrate Mine at the Antipodes

Global Industrial Economies I

Clockwise from upper left (all photos by the author): A model of the original 1912 Vemork hydropower plant behind the modernist nitrate plant and related structures at NIWM; the Humberstone engine house interior; the industrial sector with chimney at Humberstone, and Humberstone engine house exterior.

On the other side of the globe from Norway, high upon the plains of the Atacama Desert lie the remains of around two hundred Chileansalitreras, or nitrate mines, strewn across the strip of nitrate-rich earth snaking north from Antofagasta to Pisaqua. A 1912 article in Scientific American notes that the nitrate produced at Rjukan was called “Norwegian saltpeter…in distinction from Chili saltpeter. Chili, as is well known, has hitherto been the only country from which this absolutely necessary product could be obtained for agricultural fertilizing processes.”3 Before factories like Rjukan were able to chemically synthesize nitrate for use in fertilizers and explosives, the powdery white saltpeter had to be laboriously extracted from the earth. And whereas saltpeter mining in the Atacama was mostly unskilled work, the chemical manufacture of nitrate in Rjukan required training and precision. Indeed, the process employed at Rjukan, through which nitric acid, chemically manufactured using nitrogen pulled from the atmosphere, was used to decompose limestone, eventually put the majority of Chilean salitreras out of business.

Early nitrate mines provided workers with scant social services or recreation. Those few salitreras that survived the advent of synthetic nitrate were forced to change and adapt. I saw evidence of this in December, when I visited the UNESCO site of Humberstone near Iquique. During the 1930s, by which time the Chilean government had seized partial ownership of the nitrate industry, Humberstone entered an era of worker reforms. In its focus on worker life and welfare, the new version of Humberstone looked a little more like Rjukan and idealized factory towns elsewhere in the world. The plaza at Humberstone’s core is ringed with an Art Deco hotel and swimming pool, a shaded marketplace and public fountain, a pulperia (or general store), and a Pueblo Deco theater. Humberstone at first appears as a ghost town, devoid of life and living history. But each year for “Saltpeter Week,” the families of pampinos past return to the town to celebrate their ancestors and the unique culture of Chile’s Atacama nitrate mines.4

Though Rjukan’s early twentieth-century boom entailed the bust of many, many salitreras, the Norwegian factory town was not immune from the vicissitudes of the global industrial economy.

Omuta: One-Industry UNESCO City Transformed

Global Industrial Economies II

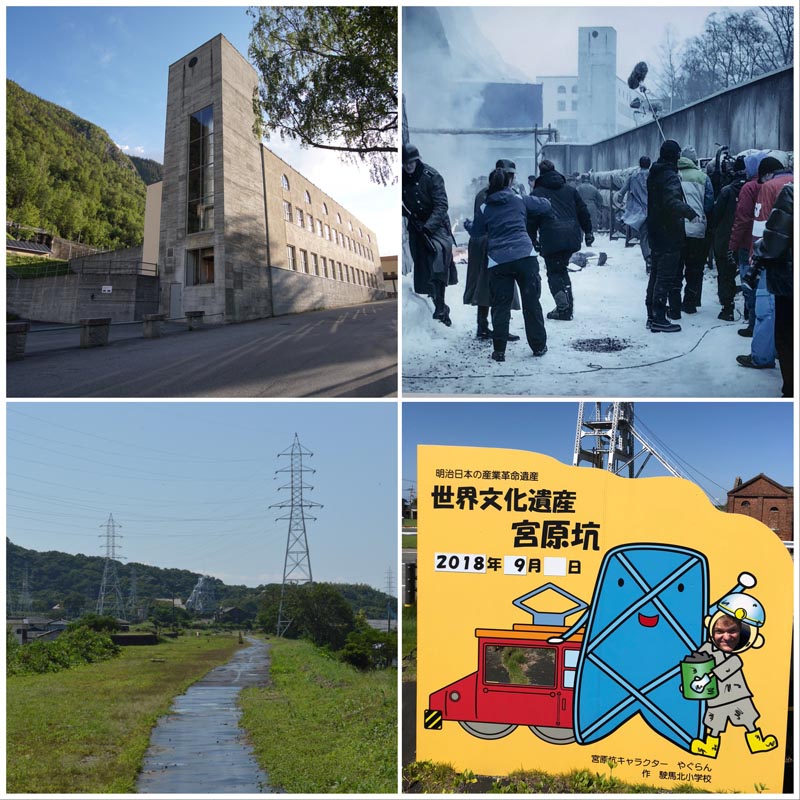

Clockwise from upper left: Part of the Såheim complex that was rebuilt for the shooting of “The Heavy Water Wars” miniseries; a production photograph from this miniseries seen on an interpretive sign at the Såheim site; a photo opportunity at one of the Meiji-era Miike coal pits in Omuta, Japan; and the long, hot rail corridor trail between the Miyanohara Pit and the Manda Pit in Omuta.

The pivot away from a purely industrial economy has radically transformed European towns like Rjukan. In 1963, Norsk Hydro changed the technologies it was using to make ammonia and moved its production facilities to the Norwegian coast. As a result, the town of 9,400 lost 1,500 jobs. The situation worsened when Norsk Hydro completely stopped production of ammonia and ammonia nitrate in Rjukan in 1989 and 1991, respectively. Across Norway, Rjukan became a kind of cautionary tale of a one-industry town in a post-industrial Europe.5 While the situation has improved somewhat since the closing of the factories, the docent I spoke with at the Norwegian Industrial Workers Museum reported that a single-family house can be had in the valley for a fraction of the price of an equivalent property in Oslo.

Of course, the plight of the one-industry town is not unique to Norway. A number of the sites that comprise Japan’s UNESCO-inscribed Sites of the Meiji Industrial Revolution fall into a similar category, as the sites of once-booming industries gone bust. Omuta, a coastal city on Japan’s southernmost main island of Kyushu, was formerly a prosperous coal town critical to the early industrialization of southern Japan. Unlike Rjukan, whose linear, valley-bound topography creates a certain feeling of density, Omuta by contrast faces the challenge of low-density heritage, with sites spread out across the city at a distance that is bikeable but questionably walkable. Indeed, I spent a long, hot day tracing old rail corridors and hiking down city streets peppered with shuttered storefronts. Nonetheless, as in Rjukan, Omuta’s recent UNESCO inscription seems to have breathed some new life into the city. Signs for the UNESCO sites are everywhere, and Omuta’s kawaii miner mascot flits across the signage for the major coal sites across the city. But despite the clear enthusiasm on the part of civic leaders and tourism promoters for the new Miike UNESCO sites, I saw no other tourists at any of the three UNESCO sites we visited in Omuta.

Today, Rjukan’s surplus housing, leftover from its more prosperous industrial past, has been repurposed as housing for resettled refugees. Even compared to cosmopolitan Oslo, Rjukan felt notably diverse. Recent headline-making investments such as the solar mirror and the restoration for the shooting of The Heavy Water War have enlarged Rjukan’s cultural footprint if not spurred a full-on renaissance.

Arc-et-Senans: Industrial Architecture Parlante

Industrial Architectural Expression I

Clockwise from upper left, all photos by the author: The Såheim hydropower plant (1915); the director’s house between the two factory buildings at the Royal Saltworks of Arc-et-Senans where salt was extracted from saline marsh water through evaporation; one of the ornamental salt flow details from Arc-et-Senans; the guardhouse at Arc-et-Senans with its artificial grotto; the entrance with exaggerated columns at Såheim; an ornamental bay window at Såheim.

When Rjukan’s Såheim Power Plant opened in 1915, it was the largest hydropower plant in the world. Designed by Olaf Nordhagen and Thorvald Astrup, it was nicknamed “the Opera,” a reference to the elegant architectural treatment of this industrial structure.6 Along the stripped neoclassical facade facing in towards town, the massive stone pavilions at either end offset a luminous row of arched windows, behind which sits the generating room. With its recessive stepped cornices and zig-zagged carved ornament, there is also something ancient about its form, a kind of abstracted, primitive styling that could read either as Viking or pre-Columbian. Nordhagen and Thorvald’s building is not merely a power plant, but an architectural statement that simultaneously conveys a progressive approach to energy, and roots its forms in the Norwegian landscape and its history.

This notion of an industrial building whose symbolic architectural function is perhaps equally as important as its productive capacity dates all the way back to Claude Nicolas Ledoux’s design for the Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans, France (1775-78). Ledoux’s architecture parlante (or speaking architecture) not only conveyed ideas about worker reform and efficiency in production, but the structure of power at the site and the importance of salt manufacture to the French royal government. Though the late eighteenth-century saltworks are a standard of the architectural history survey canon, I was nonetheless unprepared for the raw power of Ledoux’s geometries when I visited in May. The crystalline saltwater that issues forth as stone sculpture from artificial drain pipes on almost every building seem especially vivid and realistic after the lingering moisture of a passing rainstorm. And the towering composite columns of the Director’s House are far more imposing than textbook photographs can convey.

While Såheim lacks the overt, literal representation of Arc-et-Senans, its dramatic ground-level windows provide an equal view in as well as out, revealing an exalted generating room with moulding and fine interior finishes. Resting on rusticated foundations, and with column bases that take on a modicum of the foundation’s distressed texture, the bulk of the plant’s mass seems to be growing out of the rock of the mountain itself—recalling the inextricable link of mountain topography and water in Rjukan’s hydropower landscape. And those zig-zags? Perhaps more than abstract ornament, they are simultaneously water flowing and the waves of electricity subsequently generated.

Zollern II/VI Colliery: Industrial Architecture as Showpiece

Industrial Architectural Expression II

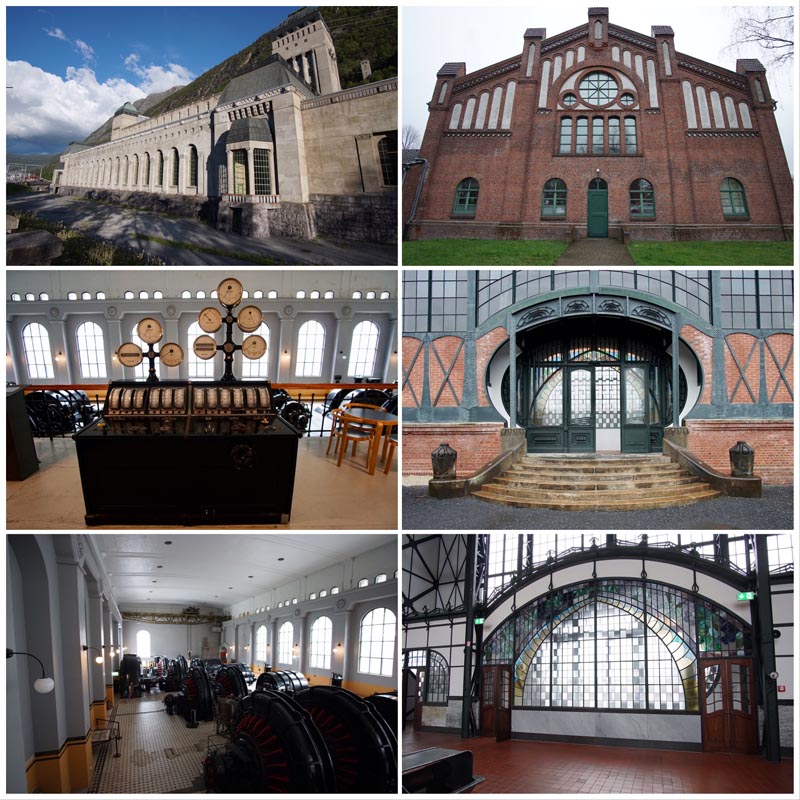

Images on the left are of Rjukan (top from Såheim, 1915; bottom two from Vemork, 1912); images on the right are from Zollern II/VI Colliery (1898-1904). Architect Paul Knobbe designed Neo-Gothic brick above, and Bruno Möhring designed Art Nouveau stained glass and wrought-iron entry seen at the Machine Hall in the two images below.

One of the first things I noticed in the interior of the Machine Hall at the Zollern II/VI was the setup for a bar, along with a smattering of high tables and other event paraphernalia. A wedding at a suburban industrial heritage site in the Ruhrgebiet region of Germany might seem at first a little far-fetched (or at least possess a very niche market of architectural historians), but the Zollern II/VI Machine Hall exemplifies the notion of a “palace for industry” perhaps more than any other site I’ve visited. The elaborate Jugendstil entrance is a riot of curves and polychrome stained glass. The red tile floor sets off the brawny silhouettes of the remaining machines. An immaculately-preserved instrument panel straddles the line between art and science, its marble casing both functional as insulation and an integral ornament within this grand industrial gesamtkustwerk.

The architecture of the Zollern II/VI Colliery (today an LWL Industrial Museum) charts the changing stylistic trends of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, spanning from a sturdy Northern European Neo-Gothic to the delicate Art Nouveau of the Machine Hall. But the entire colliery campus is connected by a shared belief that industrial architecture should be more than functional. Unlike the Albert Kahn school of industrial design, which focused the majority of stylistic ornament onto the administration building alone, Zollern II/VI suggests that all industrial structures are capable of elevation and perhaps even celebration.

This same belief in the “palace for industry” can be observed in the power plant at Vemork, and the subsequent one at Såheim. With the international press eager to spotlight the world’s largest hydropower system at the time, Såheim and Vemork are each symmetric, stylistically coherent, and symbolically overt. However, one major difference though, is that while Zollern II/VI is built on flat land where the only hills are slag heaps, the hydropower plants of Rjukan are inextricably linked to their topography. It is impossible to photograph either without also capturing the precipitous sides of the Vestfjord Valley. They are stone blocks seemingly carved from the land, rather than ornamental gems only visible in their entirety from the dizzying heights of Zollern II/VI’s winding tower.

Port Sunlight: Architectural Diversity and Garden City Ideals

Industrial Architectural Expression III

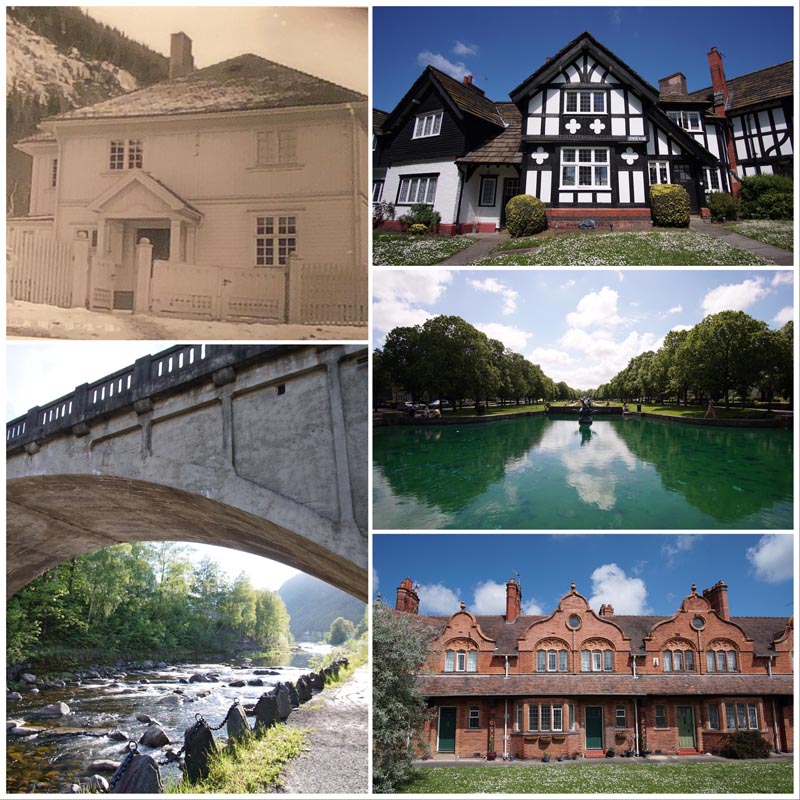

On the left: Archival image of administrator housing at Villaveien, 1913 in Rjukan (NIWM) and below, the path along the Måna River. On the right: three images of Port Sunlight, highlighting the architectural eclecticism of the housing (based on vernacular precedents in the Lancashire region) and in the middle, the formal, geometrically-planned green space of “The Diamond.”

Like many other early twentieth-century company towns, Rjukan was strongly influenced by the Garden City movement. Norway’s Egne hjem (Own Home) movement, based on an equivalent program in Sweden dating to the late nineteenth-century, promoted home ownership and the building of new Garden Cities. As with contemporary Garden Cities across Western Europe and North America, Norway’s new towns emphasized hygienic modern living along with access to green space, education, and social services.

Garden city planning and reformed residential architecture also characterize Port Sunlight, the company town near Liverpool, England established in 1889 by soap mogul William Lever. Port Sunlight deploys many of the Garden City Movement’s key features, including super blocks, communal green spaces, and garden allotments. Like the Own Home houses of Rjukan, each Port Sunlight house included several rooms over two floors and its own kitchen.

To meet housing demands in the Vestfjord Valley, the Rjukan Town Construction office drafted 140 different house designs for the town over the course of 15 years starting in 1908. With a similarly capacious architectural program, Port Sunlight is the work of 30 or so architects, working in a variety of eclectic registers all based around the regional vernaculars of Lancashire and neighboring Yorkshire. However, since Port Sunlight was overseen for much of its development by its founder and his selection of hand-picked architects, the Port Sunlight plan has a much greater sense of urban cohesion, despite its stylistic variation.

The architectural legacy of the Own Home movement in Rjukan is not immediately obvious, though I did appreciate the opportunity to spend the night in some original worker housing that looked like those in photographs I’ve seen of the duplex-style detached Own Homes. Ultimately, owing to Rjukan’s historical employment insecurity, the Own Home housing never really caught on “as an owner-occupier concept.”7

Workers Assembly Building, Copenhagen: The Public History of Labor

Industrial Architectural Expression IV

At upper left, the exterior of Rjukanhuset, constructed c. 1930 and photographed in the 1940s. At upper right, a photograph of the same building’s interior from around the same time (both photos from NIWM). Below, a photograph by the author of the Workers Assembly Building (1879) in Copenhagen, which today is the Arbejdermuseet, or Workers Museum.

The center of visitor interpretation at Rjukan is the Norwegian Industrial Workers Museum at Vemork, the former hydropower plant. On arrival, we crossed the familiar suspension bridge (it looks just like it did in the miniseries!) over the treacherous ravine, and then hiked up the side of the valley to reach this imposing, rusticated stone building. A number of structures and artifacts line the path, including one of the upgraded turbines that turned in the Vemork hydroelectric plant and the sod-roofed radio shack where the celebrated Norwegian saboteurs communicated with Allied intelligence. The former power plant has been subdivided into a number of smaller exhibits as part of the Norwegian Industrial Workers Museum: there’s the story of the WWII saboteurs, a exhibition about Rjukan as a company town, a more technical look at how the plant and associated fertilizer factory functioned, and when I visited, an exploration of the 8-hour work day in Norway.

Norway’s late industrialization and its proximity to the Soviet Union led to a particularly radicalized workforce following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. Indeed, it’s been 100 years since the workers of Rjukan “took the eight hour day,” that is, walked off the job after eight hours as a nonviolent collective labor action. The architectural manifestation of worker power and pride in Rjukan is the Folkets Hus (later renamed the Rjukanhuset), a 1930 structure that included “meeting rooms, a theater, a cinema and a restaurant.”8 The restrained, symmetrical facade of the building, as seen in the 1940s photograph above, shows the influence of the fashionable streamline moderne and the International Style. However, the idea of a “house of the people” has its roots in much older European traditions of union and worker halls. The Arbejdermuseet (Workers Museum) in Copenhagen occupies an original Workers Assembly Building, constructed in 1879. If examples like those discussed above at Zollern II/VI and Såheim were “palaces of industry,” workers buildings like the one in Copenhagen and Rjukanhuset were truly “palaces for the people.” In Copenhagen, the interior of the hall is almost basilican in plan, framed with balconies supported by decorative iron brackets, which frame carved wooden reliefs depicting the various trades. A mural at the front of the hall shows a pre-industrial, pastoral landscape. The elaborate ceiling pendants and herringbone floors further transform the hall into a sumptuous setting where labor is accorded the splendor normally reserved for the bourgeois. Though the Rjukan hall has been updated to reflect modernist, machine-age ideals, the same idea of dignity and solidarity in labor persists. Today, in recognition of the lack of UNESCO sites related to organized labor, the Workers Assembly Building in Copenhagen, along with eight other worker halls constructed between 1874 and 1938 comprise a serial nomination on the World Heritage Tentative List.

Workers’ Museum, Johannesburg: Worker Housing & Power

Industrial Architectural Expression V

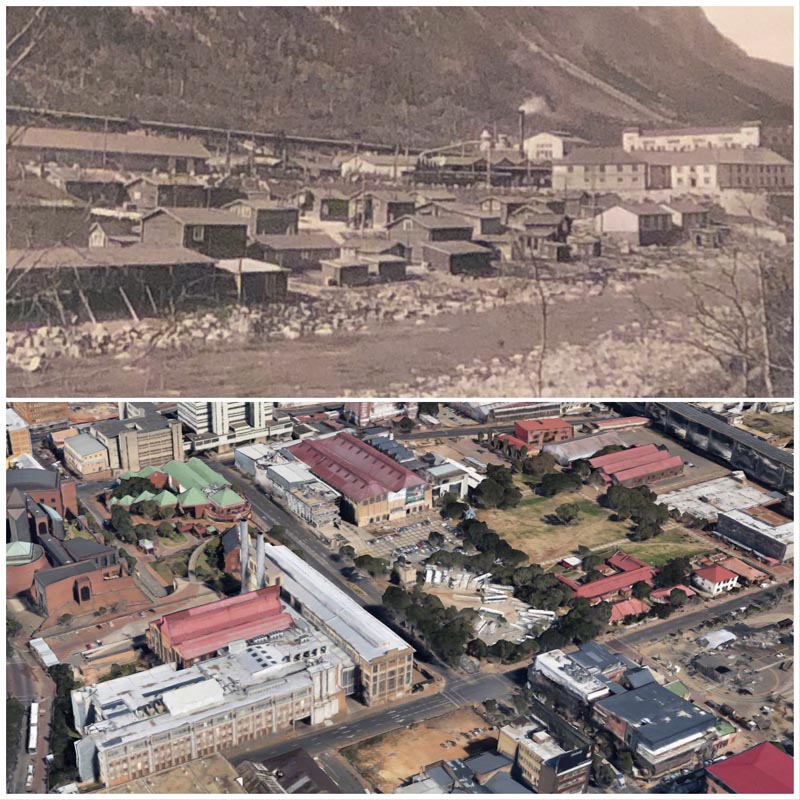

Above: Archival photograph of Såheim Old Town, 1925 (NIWM). Below: GoogleEarth view of Newtown, Johannesburg with Worker’s Museum at the center right.

Of all of the architectural gradations, distinctions, and physical separations made within worker housing, the disparities within employee housing were perhaps nowhere more stark than in apartheid South Africa. Under apartheid, race determined which workers lived in cramped, sometimes prison-like dorms versus small, reasonably equipped single-family houses. At the Workers’ Museum in Johannesburg, one of the few surviving black worker compounds has been converted into a moving interpretive space. Along the back side of the lot sit the larger, detached dwellings where dwelt the white workers, who were accorded the majority of skilled jobs and administrative positions.

In Rjukan, the gap between the haves- and have-nots was not based on race, but rather on job description. Despite Eyde’s efforts to provide adequate housing in Rjukan, the town grew faster than the Town Construction Office was able to build houses for incoming workers. Rjukan’s Old Town became a slum where cheap boarding houses and poor sanitation prevailed. One resident reported a family of seven living in 10 square meters (or a little over 100 square feet).9 By contrast, the all-male boarding houses for clerical workers and administrators offered far better conditions than those in the makeshift housing of Old Town. One young clerical worker describes his experience at Ingeniørmessen (the engineer’s housing):

”Messen” was a bit of an adventure. A huge, light dining room, a cozy smoking room with a luxurious fireplace. A lounge with a piano and deep leather chairs and every man in his own bedroom. The furniture was all white, light, friendly, and wholesome. Naturally there were W.C.s, baths, electric lighting, central heating.10

Today, part of the Ingeniørmessen complex and the other men’s boarding house, Mannheimen, are still standing. In South Africa, most worker compounds, particularly those occupied by black African workers, have been largely demolished since the end of apartheid, an architectural silence in the history of the country. However, as the troubling legacy of European colonialism and exploitation continues to unfold in Africa, many people from African countries are seeking a better life in Europe; in 2019 approximately 31% of Norwegian residents with refugee background were from African countries.11 Rjukan’s former worker housing has become part of a global landscape of refugee resettlement, and Mannheimen currently serves as a reception center for asylum seekers in Rjukan.12 In this way, the ongoing saga of dislocation and refugee movement ties Africa’s colonial past to Norway’s postindustrial present.

Gunkanjima: Digital Access to Industrial Archaeology

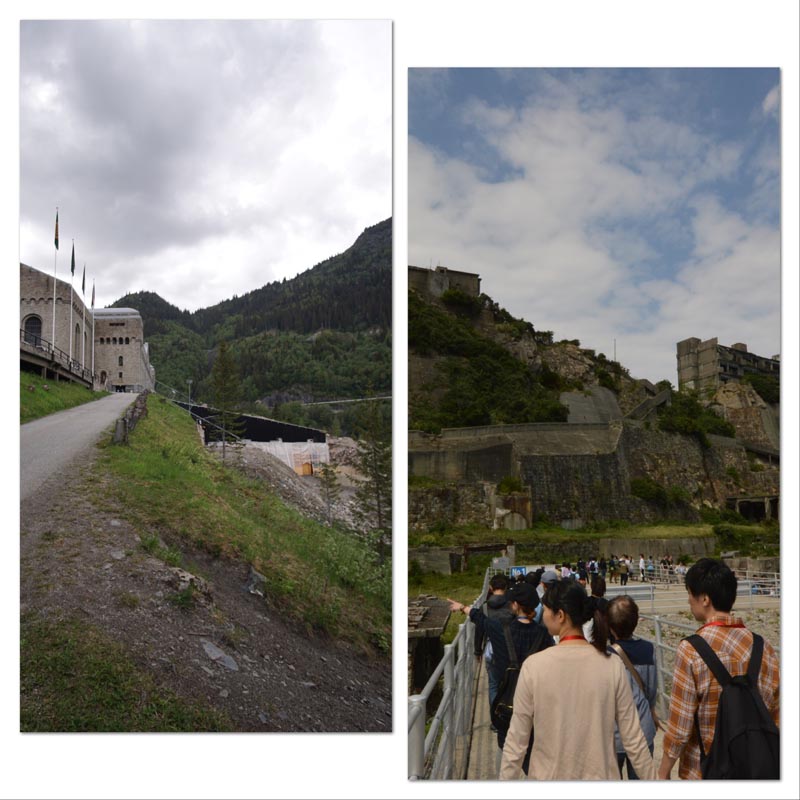

Reuse and Interpretation I

Left: The industrial archaeological dig site of the Heavy Water Basement down the hill from the Vemork hydropower plant in Rjukan. Right: Exploring Gunkanjima (Hashima, Japan) through the sequence of controlled views on the three concrete platforms open to the public.

—

Below the castellated fortress of the Vemork hydropower plant lies a fenced archaeological site: the concrete and rebar remains of the nitrate-producing fertilizer factory that was demolished in the 1970s. When Vemork was closed in 1971, the fertilizer plant was demolished shortly thereafter, despite the historical significance of the structure in WWII history as the site of occupied Norway’s heavy water production. In 2017, initial excavations of the demolition site revealed that the basement where heavy water had been produced was still largely intact. Since then, workers have been slowly removing rubble from the site, and there are long-term plans to convert the site into a space accessible to visitors. In the meantime, the site is digitally accessible as a 360° walkthrough on a large screen in the Norwegian Industrial Workers Museum at Vemork.

The challenge of engaging visitors with sites that, for reasons of safety and building preservation, are off limits to physical access brought me back to Gunkanjima, or Battleship Island, off the coast of Nagasaki, Japan. As a previous SAH blog post documented, only a small percentage of Gunkanjima can be viewed by visitors, from a sequence of three connected concrete viewing platforms. The rest of the 0.024 sq mile (0.063 sq km) island is off-limits to the public. However, the new Gunkanjima Digital Museum provides a range of digital experiences intended to deepen visitor engagement with the island and provide additional context for the site’s built environment, including its proliferation of early modernist concrete housing. As I noted in a post for the National Historic Trust’s Preservation Leadership Forum Blog, the narrative conveyed at the Digital Museum is largely sanitized and focused around booster-ish themes including community building and national industrial development. That said, the variety of VR and augmented reality experiences along with digital projections on physical models provides a richer architectural and spatial understanding for the inaccessible parts of the island. As excavation and construction in the “heavy water basement” at Rjukan continues, some of these same devices might provide an even more fully-articulated and cohesive sense of space.

Battersea: Power Plant Redeveloped

Reuse and Interpretation II

Clockwise from upper left: The generating hall at Rjukan’s Vemork hydropower plant; a model of the Battersea Power Plant redevelopment project; Battersea Power Plant under construction; and the uphill approach to the Vemork plant.

Once the hydropower core of Norwegian production, hailed in international journals as “one of the world’s greatest power plants,” the plant at Vemork has been refashioned into the Norwegian Industrial Workers Museum; its AEG dynamos silent and inert.13 Vemork’s obsolescence is largely one of scale and technology, rather than changing energy policy. Norway’s hydropower history is very much in-line with its present, in which over 90% of the country’s mainland power is hydroelectric. The same can not be said for much of the rest of the world, where coal-burning generators are giving way only slowly and reluctantly to other forms of energy production. This stilted transition is playing out in dramatic fashion along the banks of the Thames in London.

One morning in June, I took the River Bus from Chelsea Harbor to Battersea in London. There, the Battersea Power Plant, that brick Art Deco behemoth designed by Giles Gilbert Scott and J. Theo Halliday, is currently shrouded in scaffolding and ringed by graphically compelling construction barricades. This intervention comprises Europe’s current largest industrial adaptive reuse development. Originally built in two parts from 1929-35 and 1937-1955 (Battersea A and Battersea B), the plant was one of the several coal-burning “superstations” built in London, and from 1933 to 1983, it supplied up to 20% of London’s power demands. Already branded, marketed, and ready for buyers, the construction site comes with its own heritage trail, app, marketing suite, and interpretive center. I downloaded the app and followed the first few stops in the audio guide until construction barriers prevented me from advancing any further. Then I tried the “Director’s Door” experience, an augmented reality tool that lets the viewer peer virtually into the former plant director’s office in all its Deco opulence. Over at the interpretive center, a model of the redevelopment project shows the original brick structure with its four iconic stacks crowded by curvaceous residential complexes, some designed by noted starchitects. Such are the dangers of being an iconic power station in a major city center. Not every London power plant gets to be the Tate Modern.

In contrast with the siege of construction sounds at Battersea, post-industrial Rjukan feels more like a rural idyll—the loudest roars are still the natural waterfalls plummeting down the valley after a rainy spring. Protected by its UNESCO status, the valley is also remote enough from Oslo that Vemork won’t be transformed into loft apartments or artisanal coffee shops anytime soon.

Sewell: Topographically Challenging Company Town

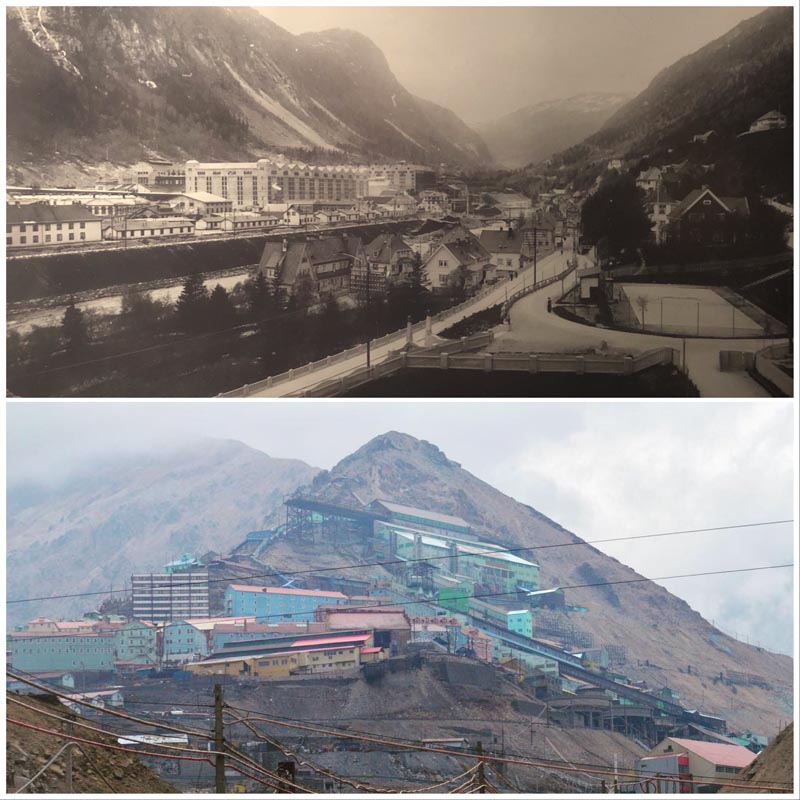

Geographies of Industry I

Above, archival photograph of Såheim, Vestfjord Valley from 1916 (NIWM); below, a view looking up towards the abandoned copper mining town of Sewell in Chile.

By Norwegian standards, Rjukan is something of an outlier. Towns designed, built, and owned by private companies like Norsk Hydro are far less common in Norway, as compared with other places I’ve traveled over the past year. Rather than conforming to an ideal geometry, the shape and layout of the town is tightly constrained by the shape of valley. As a result, Rjukan is foremost a linear town. Sam Eydesgate, the Main Street, serves as the primary artery that connects the residential and industrial sectors of the town.14 The railroad spine, which runs down the Vestfjord Valley and comprises part of the Rjukan-Notodden UNESCO landscape, also forms a crucial element of the linear city’s infrastructure.

Of the other company towns I’ve visited, only the contemporaneous company-owned copper mining town of Sewell, high in the Chilean Andes, exceeds the extreme topographic challenges faced at Rjukan. Founded in 1905 as Chile’s first copper mine company town, Sewell is an almost cubist conglomeration of timber-frame houses and public buildings. Akin to the Sam Eydesgate corridor, the entirety of Sewell’s plan centers around the grand escalera , or great staircase, which serves as a sloping pedestrian transportation spine connecting housing, recreation, education, and industrial structures.

Certain portions of both Sewell’s and Rjukan’s settings are more desirable than others, and as such, the geography also reflects the human landscape of power and authority. At Sewell, the higher reaches of the hillside were reserved for the single-family homes of Anglo-American administrators (“A Role” workers). Although most of single family houses were lost before preservation efforts began in the 1990s, the luxurious El Teniente Club remains. In Rjukan, the valley is in shadow from September to March. In springtime, the first rays of sunlight hit the higher reaches of the western slope first, making this area desirable to well-paid staff and administrators. This more affluent western slope tended to more closely follow contemporary architectural trends. In addition to more stylistic variety, better build quality, and bigger houses, some of these administrator homes also featured ornamental gardens.15

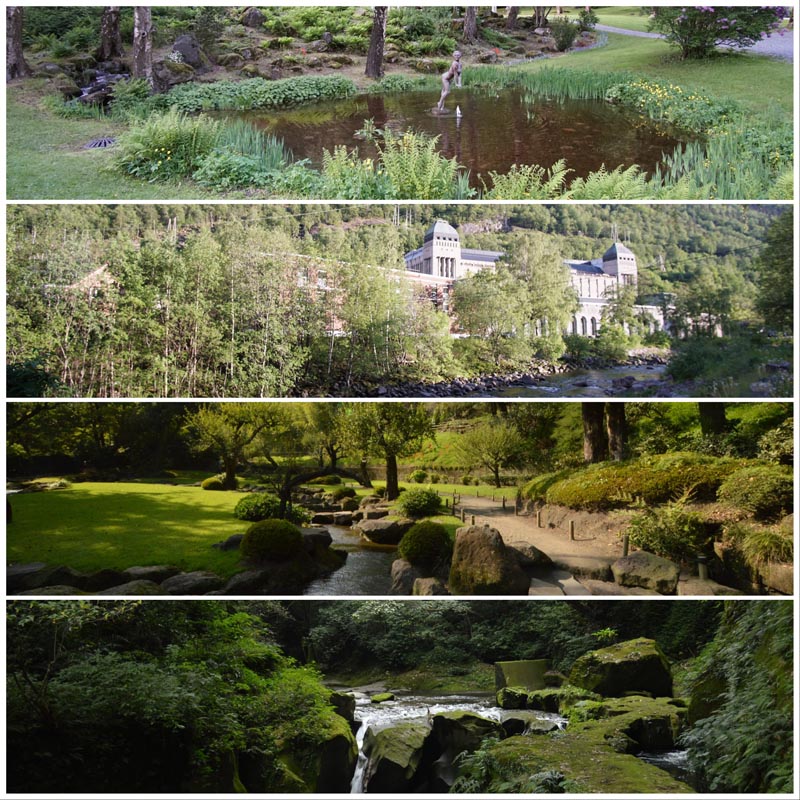

Shuseikan: Landscape of Water Power

Geographies of Industry II

From the top: An ornamental water garden on the grounds of one of the town’s villas; Såheim hydropower plant and the Måna River; the functional and decorative waterscape of Shuseikan; and the Sekiyoshi Sluice Gate of Yoshino Leat.

Only in Norway’s vertiginous interior could a budding capitalist like Sam Eyde amass a fortune through the “buying and selling of waterfalls.” Indeed, the entire basis of Norsk Hydro rests on the exploitation of two of Norway’s most abundant natural features: inland water sources and severe topography. After crossing the suspension bridge to Vemork, under which the Måna River runs, I climbed the hillside to where long, cylindrical tubes guide water down the natural slope of the valley to the Vemork hydropower plant. Initially, the drama and scale of the intervention recalled to me the dam at Shimisuzawa on Japan’s northern island of Hokkaido where water gushes down around a rhythmic palisade of concrete pillars and that above Vals, Switzerland, where a vast concrete crescent spans a mountainous valley. But beyond the monumentality of the hydroelectric landscape, the more that I explored Rjukan, the more that I began to see water everywhere.

The integral nature of water as natural feature, industrial power, and part of the human-built decorative landscape reminded me increasingly of Shuseikan, near Kagoshima, Japan. The site of one of Japan’s earliest experiments in iron shipbuilding, Shuseikan (1851) is both an aristocratic country house with water garden, and an industrial site. The water that flows there is not the result of happenstance but of extensive hydraulic engineering: a system of leats and sluices that channels spring water from high up in the hills above Kagoshima down to this particular coastal site. The intensive artifice and structure of this feat is largely hidden from the casual observer. It was only after I had made the harrowing journey (humorous in retrospect) up to the Sekiyoshi Sluice Gate of Yoshino Leat that I appreciated the amount of labor, materials, and alteration to the environment necessary to provide Shuseikan with usable water power. Today, the Shuseikan heritage site is still cacophonous with the sound of water rushing over ramparts, dripping off disused industrial tanks, and burbling through the manicured gardens of Sengan-en.

In Rjukan, water plays a similarly starring role in the ornamental gardens of administrators, the untamed waterfalls that cascade from the valley’s crest, and along the riverside trail that traces the Måna to where it empties into Tinn Lake.

Derwent Valley: Valley of Industrial Production

Geographies of Industry III

Lefthand side: Scenes from the High Tor path and Cromford Canal in the Derwent Vally; righthand side from top: Vestfjord Valley looking towards Såheim, 1907 (NIWM); the Måna River running past Såheim today; and a waterfall as seen from the Vemork hydropower plant.

Reaching Cromford Mills via rail is no easy feat. It took me three trains to reach my ultimate destination at the northern end of the Derwent Valley. The final stretch from Derby is a spur dead-ending in Matlock, where I found a quaint British bed & breakfast within walking distance of Cromford just a few miles south. The hike over the High Tor path to Cromford yielded panoramic views of the Derwent Valley, a world unto itself—a string of villages interspersed with meadows, manor houses, and the remains of Britain’s earliest mechanized production. The valley as industrial landscape has been a recurrent theme of my industrial explorations over the past year. Why valleys? As much as river valleys are frequently reliable sources of water for power and transit, they can also prove remote and isolated. Indeed, eighteenth-century industrialist Richard Arkwright chose the Derwent Valley in central England for his cotton mill precisely because it was difficult to reach by land—a must in an age when the threat of sabotage by “machine-breakers” seemed very real. In an era before railroads, Arkwright sent most of his spun cotton overland by pack horse to ports like Liverpool. The system of canals that followed originally won Arkwright’s support, though he reneged when he found them to be more trouble than their worth to him.

Norway’s remote mountain valleys and their cascading waterfalls were the stuff of folklore and legend—irreparably altered with the advent of hydropower. The Scientific American piece of 1912 quoted elsewhere in this story describes how “The huge ‘Kettle’ situated under the (Rjukan) falls, from which the water rose perpendicularly into the air, and from which the old ‘foss’ sent its power bass-voice out over the valley in an everlasting monotonous hum, is now almost entirely dry, and not a sound is to be heard.”16 The remoteness of Rjukan made it initially difficult to export the nitrates manufactured there, and required the construction of a 28.6 mile railway from Rjukan to Notodden, plus a ferry across Tinn Lake. Rjukan’s isolation it also made it a strategic and defensible place for the Germans to produce heavy water during WWII. Ultimately, the Norwegian Resistance forces succeeded through a stealth infiltration of the heavy water facility at Vemork that involved traversing the treacherous ravine below the plant.

Conclusion

Above: Rjukan’s central square where the solar mirror casts its light. Below left: an understated monument to Norwegian Resistance fighter Gunnar Sønsteby; below right: a monument to a woman worker in Rjukan.

On the morning we left Rjukan, the sun was already spilling onto the western side of the valley while the solar mirror cast its bright eye upon the center square, creating a pool of limpid illumination on the stones. In one corner of the square stands a statue commemorating Gunnar Sønsteby (1918-2012), a celebrated resistance fighter and elite saboteur. Compared to Sam Eyde on his grand pedestal in the square’s center, Sønsteby is depicted propped against a bicycle. In this pose, the Rjukan-born hero appears casual and nondescript. As we lingered there, a few residents could already be seen out on bikes, cycling to jobs or for pleasure. Indeed, the vast majority of post-industrial cities and towns I’ve visited are like Rjukan: places where past and present dwell side by side. Though Vemork is now a museum, Såheim is still a functional hydropower plant owned by a subsidiary of Norsk Hydro. A bronze statue (unlabeled, as far as I could discern) of a woman worker holding a mop and a bucket rests next to a popular falafel joint where teens lolled on the picnic benches in the warmth of a summer evening. These juxtapositions crystallized an idea that I’ve slowly developed through this year of global travel, and only now have put into words: that architectural heritage as public practice should not be the embalming of the industrial past but its meaningful incorporation into the present.

- Heavy water is water with a higher than usual amount of deuterium, an isotope of hydrogen. The vast majority of hydrogen atoms in normal water molecules are hydrogen-1 isotopes, I.e. protium atoms—that is, they only have one neutron. Deuterium atoms have two neutrons. Heavy water’s unique chemical properties are useful in controlling and prolonging some nuclear reactions. ↩︎

- “Discover the Industrial Adventure,” publication of the Norsk Industriarbeider Museum (Norwegian Industrial Workers Museum), 4. ↩︎

- “A Mammoth Norwegian Power Plant,” Scientific American 107, no. 4 (July 27, 1912): 76. ↩︎

- “Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works,” UNESCO World Heritage Convention, accessed July 31, 2019, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1178/. ↩︎

- “Reorganization of Norsk Hydro,” “Crisis in the community in the 1960s,” and “New clouds above Rjukan in 1988,” Rjukan interpretive text, photographed June 7, 2019. ↩︎

- “Såheim Kraftverk,” Rjukan interpretive sign, photographed June 7, 2019. ↩︎

- “An Ideal Worker’s Home,” NIWM onsite literature, photographed June 7, 2019. ↩︎

- “Folkets Hus—the house of the people,” onsite interpretive signage, Norwegian Industrial Workers Museum, photographed June 7, 2019. ↩︎

- “Housing Shortage,” on site literature at Vemork Industrial Museum, photographed June 7, 2019. ↩︎

- “Boarding houses,” on site literature at Vemork Industrial Museum, photographed June 7, 2019. ↩︎

- “Persons with Refugee Background,” Statistics Norway, accessed July 29, 2019, https://www.ssb.no/en/flyktninger. ↩︎

- “Boarding houses,” onsite literature at NIWM, photographed June 7, 2019. ↩︎

- “A Mammoth Norwegian Power Plant,” Scientific American 107, no. 4 (July 27, 1912): 76. ↩︎

- “The Big Picture,” Rjukan interpretive text in English translation, photographed June 7, 2019. ↩︎

- Ibid.↩︎

- “A Mammoth Norwegian Power Plant,” Scientific American 107, no. 4 (July 27, 1912): 76. ↩︎

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top