-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Architectural Reproduction vs. Reconstruction in Postwar Warsaw

Sundus Al-Bayati is the 2019 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

Destruction of architecture by a conquering power has often been performed as an act of cultural cleansing. To intentionally destroy a city is to deprive it of cultural and historical continuity, erasing its character and damaging its people’s sense of belonging. In recent memory, the images of ISIS destroying ancient sites and monuments in Palmyra, Syria, and Mosul, Iraq, have proliferated in the public consciousness. ISIS published chilling photos of explosives they planted in the 2000-year-old temple of Baal Shamin in preparation for the spectacle of its doom. The Nazis in Warsaw, like ISIS, used the purposeful destruction of architecture as a weapon to annihilate Polish civilization. The Nazis thought that by razing the architecture of Warsaw, they would strip the Polish people of their historical and cultural identity, which equaled reducing them to uncivilized, second-class citizens that were meant to serve the superior German occupiers. The Nazis carried out this process of deconstructing Warsaw’s architectural heritage in a methodical and purposeful manner.

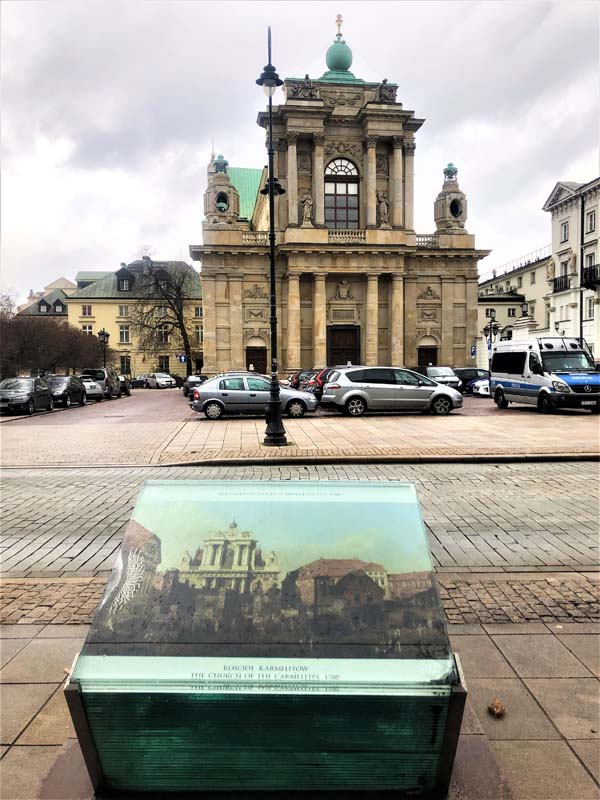

When I mentioned that I was going to Warsaw to anybody from Europe, they suggested I “go to Krakow.” I understood that the reasons behind this lack of enthusiasm about Warsaw would be very much related to my topic of interest: the consequences of war on how the city looks. The historic center of Warsaw, which was reduced to rubble in 1944, is a facsimile construction that was completed in the 1950s. It was largely rebuilt according to how the city looked like in the 18th-century paintings of Italian Renaissance artist Bernando Bellotto, known as Canaletto. Visitors to Warsaw’s Old Town come across plaques displaying Bellotto’s paintings of the building in question standing in front of the actual reconstruction (Figure 1). Reconstructing the historical quarter of Warsaw based on a representation of the city in art, one that portrays a nostalgic view of the past, emphasizes the symbolic importance of Old Town for national identity. However, its authenticity as a historical reconstruction has been widely questioned.

Figure 1. Carmelite Church, 1780 Warsaw, next to a painting of the Church by Bernardo Bellotto. This particular church, however, managed to survive the war unscathed.

From Berlin, I took a six-and-a-half-hour train ride to Warsaw. As I stepped out of Warszawa Centralna train station, a celebrated modernist building completed in 1975 (Figure 2), I was welcomed by one of Warsaw’s most controversial landmarks, an infamous product of Stalinist architecture, the Palace of Culture (Figure 3). In the following days, shrouded by overcast and gray skies, Warsaw, with its freestanding Soviet-era housing blocks, looked dreary and visually uninteresting (Figure 4–5). Of course, this is one view of Warsaw. There is a sense in Warsaw that the city is still in the process of becoming.

Figure 2. Warszawa Centralna Train Station.

Figure 3. Palace of Culture

Figure 4–5. Modernist Housing Estates, Osiedle za Żelazną Bramą, 1970, Warsaw

Warsaw is unique among other cities destroyed during World War II. The destruction of the city wasn’t only the result of fighting. It was a methodical process of destruction guided by a prewar Nazi German urban plan to dismantle the Polish city and construct a Nazi model city in its place. In 1939, the Pabst plan envisioned the annihilation of the Polish city and its people of 1.3 million inhabitants to make room for a new provisional German town of 130,000 Germans.1 Warsaw’s Jewish population were the first group targeted to achieve this extreme reduction in population size. Around 400,000 Jewish people were forced into the small area of the Jewish Ghetto and lived in overcrowded and dreadful conditions. Next, Poles were to be relocated to labor camps across the Vistula River to serve as slave laborers for the new German town. Stanislaw Jankowski, a Polish architect who was involved in the first years of reconstruction in Warsaw, expands on the unusual Pabst Plan:

“This is probably the only document in history that did not even attempt to justify destruction by arguing military necessities. On the contrary, it ordered the destruction of an entire city with the exception of military installations. The order was carried out with precision. A special staff composed of experts and scientific advisers was in charge of the operation. Warsaw was divided into areas for destruction. Corner houses were numbered. On selected buildings and statues special inscriptions were made indicating the proposed date of demolition. Special detachments known as demolition and annihilation squads proceeded to destroy the deserted city- house by house, street by street.”2

The tactical demolition of Warsaw delineated in the Pabst plan was transformed by two retaliatory episodes of destruction. In 1943, the Ghetto Uprising broke out to resist deporting the remaining Jews to extermination camps after 320,000 Jews were sent to the gas chambers of Treblinka in 1942. The uprising ended with the burning of the Ghetto and everyone inside it followed by a leveling of any structure that remained. A year later, the Polish underground resistance organized the Warsaw Uprising to reclaim Warsaw from German occupation. Tragically, the Soviet army, which was supposed to advance to Warsaw to defeat Germany, stopped at the other side of the Vistula River, allowing the Nazi army to extinguish the uprising and unleash the final blow of destruction of Warsaw in retaliation. In 1944, over 85% of Warsaw was in ruins.3

The Old Town has historically been the most representative and celebrated image of the city’s identity (Figure 6–11). The historic center of Warsaw, developed between the 13th and 20th centuries, is a vibrant place bustling with tourists, locals, and kids on school field trips. The Old Town, distinguished by its colorful facades and winding streets, was the economic and political center of Warsaw in the 16th and 17th centuries when it became the seat of Polish kings and the meeting place of the Sejms. This historical period is significant for the Polish nation, which ceased to exist as an independent state from 1795 to 1918 with the Third Partition of Poland. The urban and spatial character of the Old Town was a testament to the prosperity of the Polish state. It is because of its status as a cherished symbol of Polish culture and statehood that Warsaw’s historic center was intentionally targeted for erasure by Adolf Hitler. By destroying Warsaw, Hitler wanted to eradicate any historical record of Polish culture (Figure 12).

Figure 6–8. Krakowskie Przedmieście, prominent street constituted part of Warsaw’s Royal Route

Figure 9–11. Reconstructed Old Town Warsaw

Figure 12. Marketplace in Old Town, after the war

The reconstruction of Warsaw, and specifically the Old Town, was seen as a symbolic resurrection of Poland and the inextinguishable spirit of its people to reclaim their city and therefore, their national identity. The Old Town of Warsaw was rebuilt exactly as it was, relying mainly on representations of the city in art and other forms of documentation that took place secretly under German Occupation. Some modifications to the original buildings were made to ameliorate prewar conditions, like eliminating sections of tenement housing and widening courtyards in what were dense and overcrowded housing estates. The replicas might resemble the old architecture on the outside but their interiors were often of modern construction. Reconstruction debates concluded that it was more important to recreate the very image of Warsaw the Fuhrer meant to annihilate in order to give people back what was taken from them. While the reconstruction of Old Town might stem from a nostalgic vision of Warsaw, it is celebrated as an extensive and faithful reconstruction of a historic center, which earned it a place on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1980.

Much of the chaotic and haphazard character of the urban fabric of Warsaw is attributed to the rapid development of the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century that triggered a massive population growth (Figure 13). Warsaw was under Russian rule until 1918, which not only prevented the expansion of the city outwards to accommodate the population increase, but did not instate regulations and policies to deal with urban growth.4 Plans to reshape Warsaw to improve its urban conditions have been in the works since 1918 when Poland regained its independence and continued during the period of World War II. Stanislaw Jankowski, who was an SOE agent, a Polish resistance fighter, and an architect, discusses secret town planning and architectural studies that took place in Warsaw during the German Occupation. Jankowski’s account sheds some light on the preemptive efforts of the planning department of the Warsaw Municipal Council, the Faculty of Architecture of Warsaw Technical University, the Studio of Architecture and Town Planning, and others to secretly prepare plans for Warsaw’s reconstruction after liberation and to document the city’s historical monuments should they get destroyed. These efforts by Polish architects and planners facilitated the process of rebuilding after the war and were an example of the Polish resistance against cultural and historical annihilation perpetrated by the Nazis. Jankowski elaborates on the secret planning efforts:

“This conspiratorial town-planning activity, carried out in conditions of terror unleashed by the Gestapo, implied awareness that planning itself constituted a form of struggle against the invader, and it also expressed the need for continuing professional work and for making preparations for new tasks that were to come.”5

Figure 13. A clash of architectural styles, Warsaw

Representations of Warsaw in Polish Art

Bernardo Bellotto’s paintings of Warsaw (Figures 14–16) are the most well-known representations of the city in its prosperous era and became crucial blueprints for rebuilding the historic quarter after the war. Bellotto, who became a court painter to the king of Poland in 1768, executed accurate cityscapes of buildings and squares of the historic center of Warsaw. Even if Bellotto’s depictions are known to be embellished for artistic purposes, the survival of these paintings proved crucial in recreating the image of Warsaw’s golden age that was intentionally wiped out during the war.

Figure 14. Bernardo Bellotto, Church of the Holy Cross in Warsaw, 1778. Photo: Royal Castle in Warsaw.

Figure 15. Bernardo Bellotto, Miodowa Street, 1777. Photo: Royal Castle in Warsaw.

Figure 16. Bernardo Bellotto, Carmelite Church in Warsaw, 1780. Photo: Royal Castle in Warsaw.

Figure 17. Marcin Zaleski , Plac Teatralny, 1838. Photo: Museum of Warsaw

Figure 18. Władysław_Podkowiński, Nowy Świat Street on a Summer Day, 1892. Nowy Swiat Photo: National Museum of Warsaw. Nowy Swiat is a major historic street in Warsaw and part of the Royal Route. It was one of the first to be rebuilt after the war.

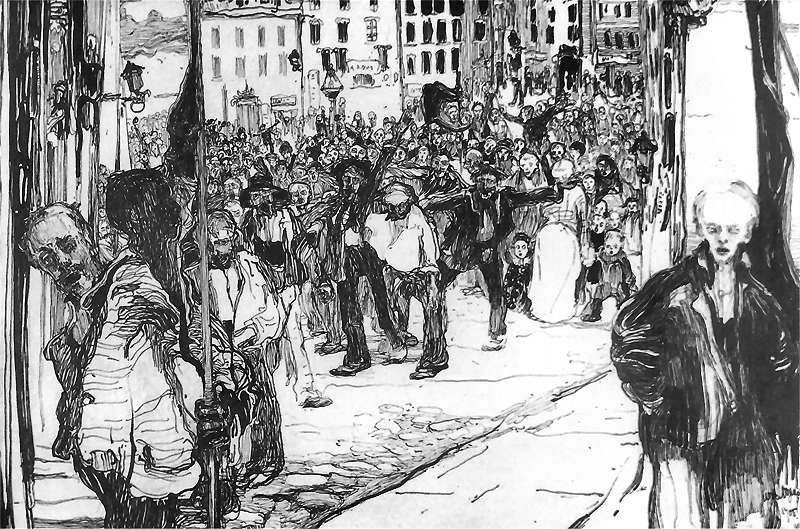

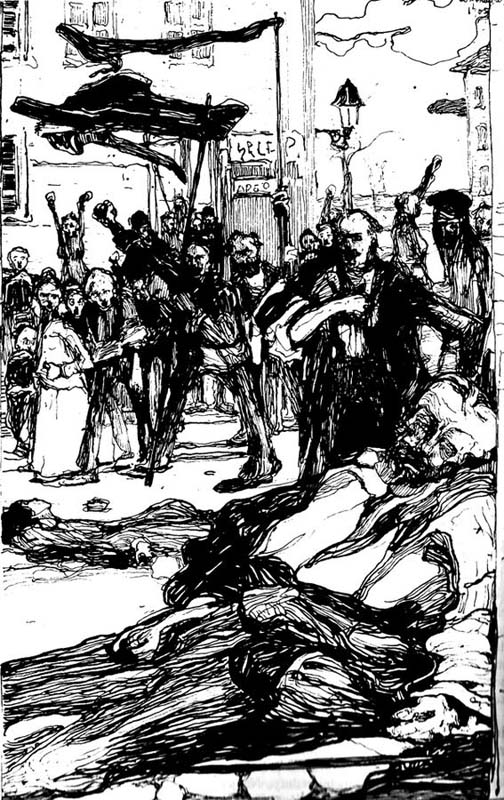

In 1905, Witold Wojtkiewicz sketched the uprising that took place in Warsaw as part of the larger revolution in Poland that began in Lodz (Figures 19–20). Across Poland, workers went on strike to demand better working and living conditions, as well as more rights and political freedom. In Witold Wojtkiewicz’s expressionist sketches, Warsaw’s Old Town is the stage where this revolution unfolds connecting the spatial and urban landscape of the city with a distinct Polish resistance similar to representations of the 1944 Warsaw Uprising in the city (Figure 21).

Figures 19–20. Witold Wojtkiewicz, Street Demonstration, 1905. Photos: www.wikipedia.org

Figure 21. The Warsaw Uprising, A Mural by Jarosław Fabis, 2016. Photo: Warsaw Uprising Museum.

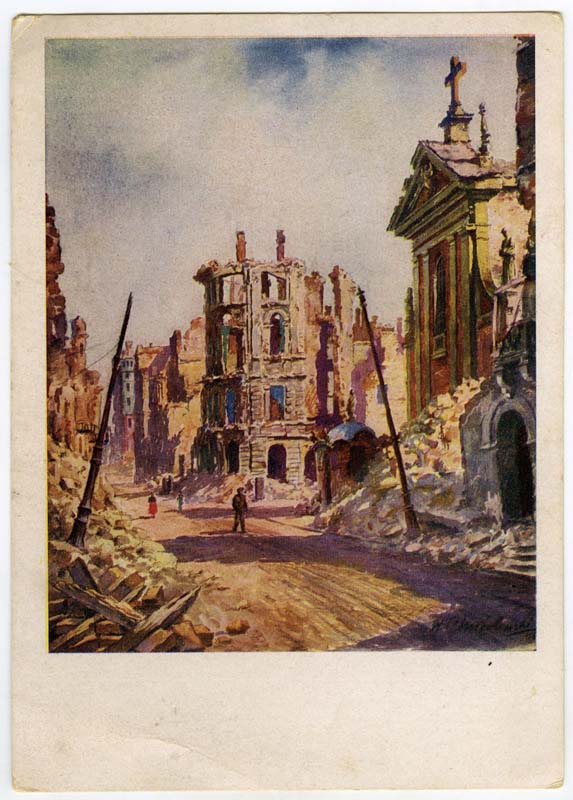

Life amidst the ruins was a reality for the many Varsovians that returned to Warsaw after the war despite the city’s unlivable conditions. Warsaw’s rubble landscapes permeated the cultural consciousness and the work of Polish artists. Although the depictions of Warsaw’s ruins were more of a documentation of its alien state after the war than a contemplative fascination with ruins typical of ruins painting.

Figure 22. Antoni Lyzwanski, Warsaw Exodus, 1945. Photo: www.owzpap.org

Figure 23. Antoni Teslar, Pigeons on Bugaj Street, 1952. Photo: Museum of Warsaw

Figure 24. Jan Wisniewski, A View of Ruined Warsaw from Praga, 1945. Photo: Museum of Warsaw

Figure 25. W. Chmielewski, Ruins of the Capuchin Church at ul. Miodowa, 1947. Photo: Museum of Warsaw.

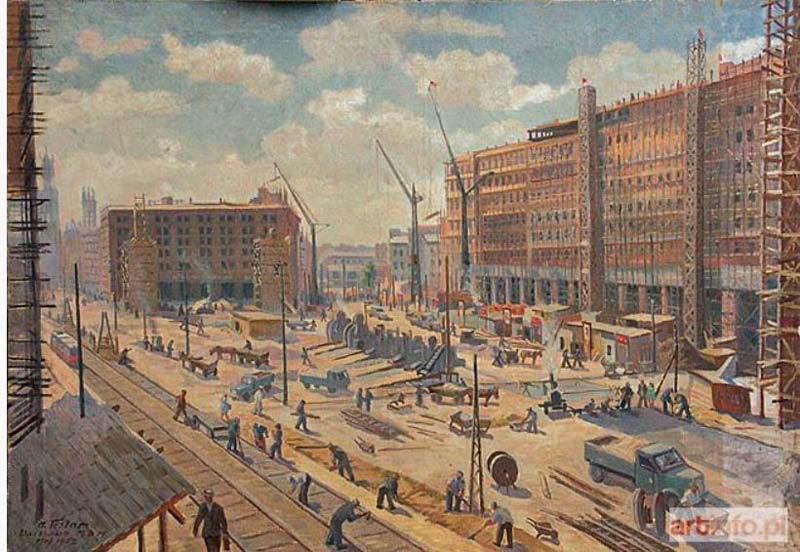

A month after the war ended, the Office for the Reconstruction of the City was established in Warsaw to begin the process of rebuilding. Planners, architects, and politicians argued over whether to rebuild the city as it was or to treat the ruined urban fabric as a tabula rasa to introduce new urban developments and architectural styles. The two paintings by Antoni Teslar in Figure 26 and 27 depict the primary approaches of postwar reconstruction in Warsaw: the historical facsimile reconstruction of Old Town, and the introduction of modern urban planning and architecture. Teslar’s painting in Figure 27 shows the reconstruction of the iconic Marszałkowska Residential District (MDM), the socialist realist residential complex that housed workers (Figure 28–30). The monumental and decorated housing blocks were the inspiration for Stalinallee in Berlin. Similarly, the construction of Constitution Square was meant to host parades and public demonstrations.6 The MDM complex was a major urban planning project that was noted for retaining the 18th century star-shaped urban fabric of the site, perhaps situating the Stalinist “foreign” architecture in an inherently Polish urban landscape, thus eliciting a sense of a cultural continuity.

Figure 26. Antoni Teslar, Reconstruction of Warsaw (Old Town), 1952. Photo: www.artinfo.pl

Figure 27. Antoni Teslar, Reconstruction of Warsaw (Marszałkowska Residential District), 1952. Photo: www.artinfo.pl

Figure 28–30. Marszałkowska Residential District and Constitution Square, Warsaw

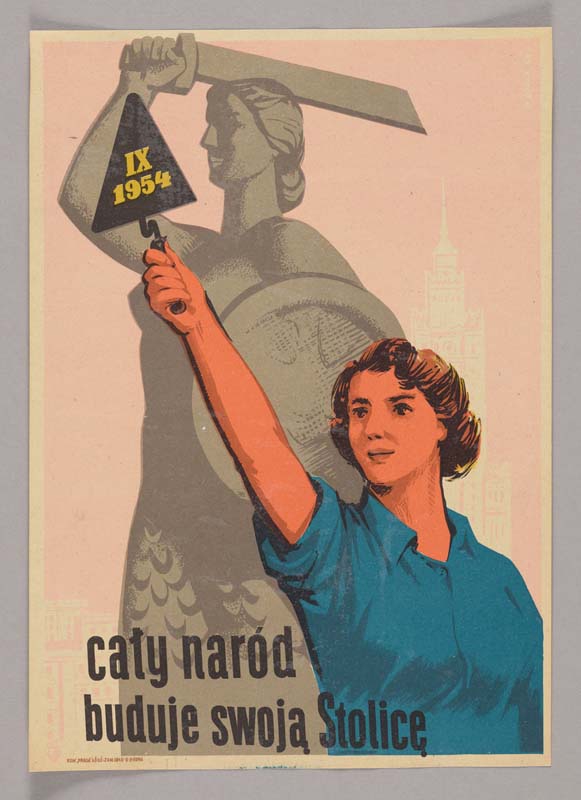

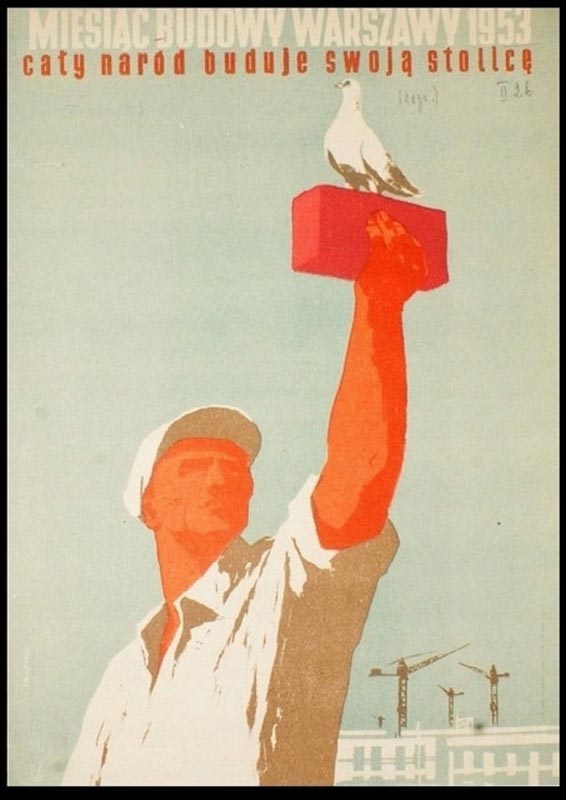

During the reconstruction years, the image of heroic Varsovians rebuilding their city was one that the Communist government exploited in its propaganda art to strengthen its own ideological and political power in Poland. Figures 31–33 show examples of these images produced around that time. Figure 31, 32 reads “the whole nation is building its capital.” The Mermaid of Warsaw is in the background in Figure 31, which is a historical municipal symbol dating to the 14th century. Figure 33 reads, “We are building Warsaw with a joint effort. We are building people’s Warsaw.”

Figure 31. Wiktor Gorka, Propaganda Poster, 1954. Photo: Museum of Warsaw

Figure 32. Propaganda Poster, Wydawnictwo Artytyczno Graficzne, 1953. Photo: www.antykwariatwaw.pl

Figure 33. Left: unknown author, 1948. Right: Witold Chmielewski, T. Tomaszewski, 1955. Photo: Museum of Warsaw

After Socialist Realism became the official style of art in People’s Republic of Poland, Wojciech Fangor painted this allegorical scene of Polish construction workers working together to rebuild Warsaw (Figure 34), connecting once again the Communist cause with the rebuilding of the Polish capital.

Figure 34. Wojciech Fangor, Murarze, 1950. Photo: Museum of Warsaw

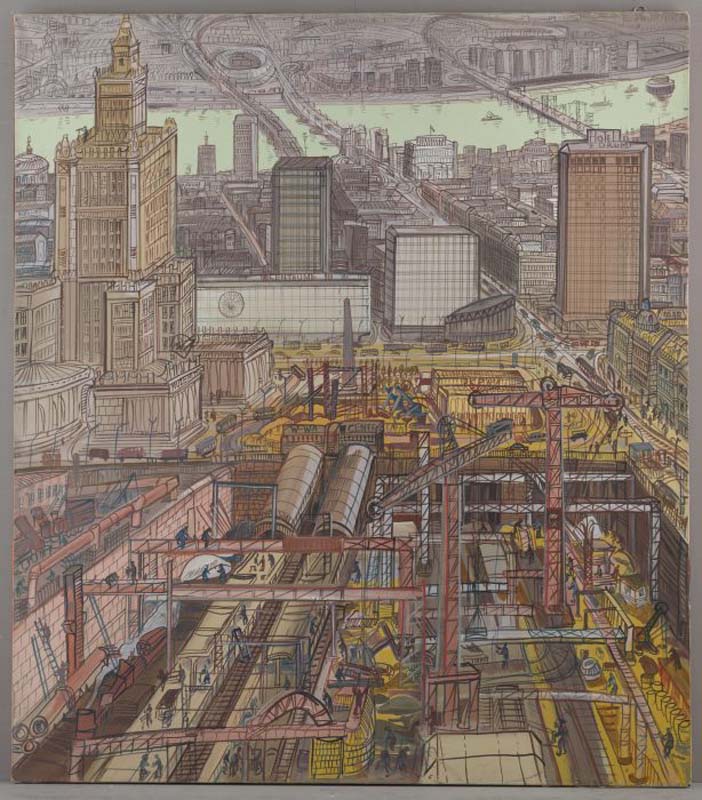

Edward Dwurnki’s painting of the Warsaw cityscape is a bit satirical in its description of Warsaw’s urban identity. The painting, as the title suggests, shows the construction of Warszawa Centralna railway station surrounded by a showcase of Warsaw’s most famous and controversial architectural gestures that transformed the character of the city, and soon to be joined by the modern innovative design of the station. The view tilts up to encompass as much of Warsaw’s urban landmarks as possible, all the result of postwar reconstruction. On the left, a foreshortened and squat Palace of Culture, the most dominating figure in the composition, as well as in Warsaw’s urban landscape. In the center-right, a notable modernist building, the Rotunda (PKO), is shown with its iconic jagged roof. Five years after this painting was completed, the Rotunda was destroyed by an explosion due to a gas leak. The Rotunda was completely rebuilt a couple of times, so that little of the original building remains. In the background, Warsaw’s major thoroughfares are depicted with forceful lines connecting the center of Warsaw with the eastern Praga district.

Figure 35. Edward Dwurnki, Construction of the Central Railway Station, 1974. Photo: Museum of Warsaw.

I did go to Krakow and I can confirm it is a more pleasant city to visit than Warsaw. After all, Krakow was spared the destruction that Warsaw suffered and survived the war almost untouched. Seeing the glaring differences between Warsaw and Krakow, two Polish cities that met different fates, one starts to grasp the lasting effects of war on the urban character of cities.

Figure 36. St’ Mary Basilica, Krakow, a prominent example of Polish Gothic architecture.

Figure 37. St’ Mary Basilica, Krakow. View of the polychrome interior murals.

References

1 Diefendorf, Jeffry M., and Stanislaw Jankowski. “Warsaw: Destruction, Secret Town Planning, 1939–44, and Postwar Reconstruction.” Essay. In Rebuilding Europe's Bombed Cities, 96. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1990.

2 Ibid, 94.

3 Bevan, Robert. The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War. London: Reaktion Books, 2016.

4 Lupienko , Aleksander. “Reading Warsaw’s Complicated Urban Fabric.” In City as Organism, New Visions for Urban Life 1, Vol. 1. Rome, Italy, n.d., 2015.

5 Diefendorf, Jeffry M., and Stanislaw Jankowski. “Warsaw: Destruction, Secret Town Planning, 1939–44, and Postwar Reconstruction .” Essay. In Rebuilding Europe's Bombed Cities, 96. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1990.

6 Dydek, Maria. “The Architectural Heritage of Socialist Realism in Warsaw.” The Uncomfortable Significance of Socialist Heritage, 2013.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top