-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

The Hidden Scars of the Spanish Civil War in Madrid

Sundus Al-Bayati is the 2019 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

On this traveling fellowship I have enjoyed the ability to access a host of masterpieces, pictures I’ve seen only in art history books or on a screen. Every time I stood in front of one of these works of art, I reminded myself of how lucky I am to be on this journey. Likewise, when I altered my travel itinerary for the fifth or sixth time to go to Spain to look at the effects of the Spanish Civil War, I was excited by the prospect of seeing artworks by prominent Spanish artists like Velazquez, Goya, and Picasso.

Pablo Picasso’s Guernica is perhaps the most well-known artwork about the tragedy of war. When I entered the room where Guernica is displayed in the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid, I was agape by the size of the painting. A collage in grey tones depicts a jumble of contorted shapes resembling figures and animals screaming in pain and sprawled on a canvas that measures 25 ft, 6in across and 11 ft, 5 in tall. The painting represents the bombing of Guernica in the Basque region by Nazi forces in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War, but it could be describing the trauma of any war.

Figure 1. Guernica, Pablo Picasso, 1937. Image from: www.museoreinasofia.es

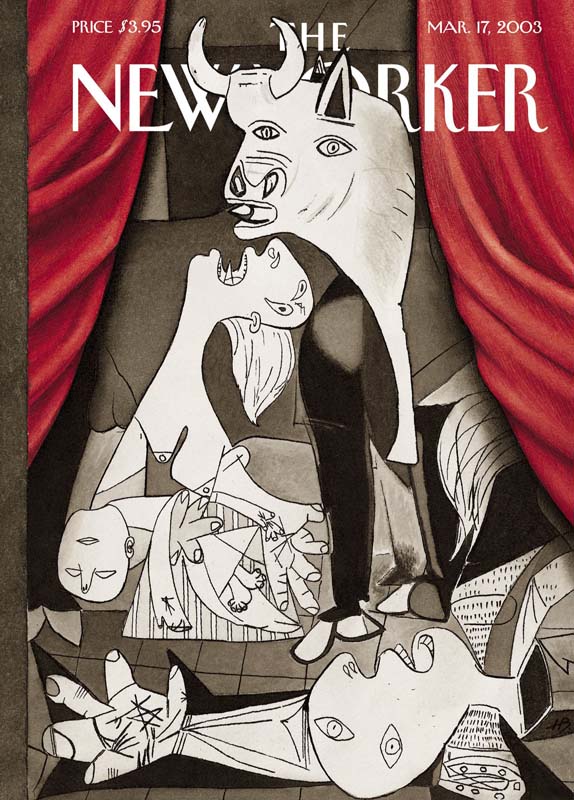

The power of Picasso’s anti-war message in Guernica involves an embarrassing and symbolic incident at the UN where a tapestry reproduction of the painting is displayed. In February 2003, U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell headed to the UN to plead his case for the war on Iraq while Picasso’s Guernica hung behind him. His staff noticed the irony of Guernica’s anti-war screaming faces and asked to cover the painting while Colin Powell gave a speech about why they should invade Iraq. The New Yorker’s cover from March 17th, 2003, (three days before the Iraq invasion) captured this moment in history showing Picasso’s Guernica draped in red curtains.

Figure 2. New Yorker cover from March 17, 2003. Image from: www.newyorker.com

During the Spanish Civil War, Madrid became a symbol of anti-fascist resistance, enduring a two-and-a-half-year siege, fighting against the rebel forces led by Francisco Franco. Madrid was the first major city in history to experience aerial bombardments of its residential neighborhoods and civilians, which was ordered by Franco as punishment and aided by German and Italian aircraft to extinguish the Republican resistance.1 For a city that was bombed and attacked for such a long time, it was surprising to find out when I got there that the traces of the Spanish Civil War in Madrid, a city that has become a symbol of resistance against fascism, were hidden and undetectable. During the Franco dictatorship, post-war reconstruction was a means to bury any evidence of Spanish resistance against Franco and his Nationalist army. By rebuilding destroyed residential neighborhoods like Arguelles, which was heavily bombed during the siege of Madrid, patching up ruined iconic buildings, and sometimes removing a building altogether as if it never existed, as in the case of the barracks of La Montana de Principe Pio, later generations would grow up unaware of the historical events that shaped their city.

The inability to read the effects of the Spanish Civil War in Madrid was not only the product of Franco’s censorship and controlled rhetoric but a characteristic of the amnesty law that was agreed on as Spain was transitioning into a parliamentary government following Franco’s death in 1975. For the purpose of national reconciliation, political parties on the left and right agreed to create the Pact of Forgetting, a law that prevented invoking the legacy of Franco and the Spanish Civil War, as well as not prosecuting war crimes committed during the war and the Francoist period. The consequences of this law permeate every aspect of Spanish material culture, including its post-Civil War architecture and monuments such as the controversial Valley of the Fallen in San Lorenzo de El Escorial, built by the dictator himself.

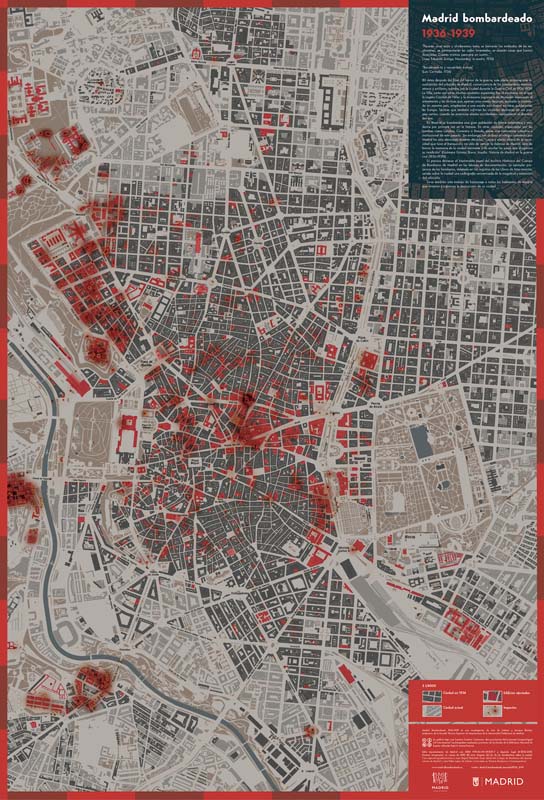

My search for the traces of the Spanish Civil War in Madrid was proving difficult, but I was aided by a book that I’ve come across by two architects and professors at the Polytechnic University of Madrid, Madrid Bombardeada: Cartografia de la Destruccion 1936–1939 (Madrid Bombed: Mapping of the Destruction 1936–1939). The book recounts the difficulties the two authors faced in their extensive research to piece together and map the damage inflicted on Madrid during the Civil War. It is supplemented by a large map of Madrid where instances of impact by bombs or artillery are registered in red, resembling blood stains. With a glance at the map, one is able to have a sense about the areas that were damaged most during the civil war. So, with map in hand, I walked around Madrid trying to distinguish what was destroyed and rebuilt and what was untouched during the war. For example, the Arguelles neighborhood, north of the Royal Palace, sustained a lot of damage during the battle of Madrid from being so close to the attacks that were launched from Casa de Campo Park.

Figure 3. Map illustrating the location and extent of the damage in Madrid during the Spanish Civil War. Image from the book Madrid Bombardeada: Cartografia de la Destruccion 1936–1939.

To understand the effects of the Spanish Civil War on the urban environment, I decided to look more closely into two iconic sites in and around Madrid: La Montana de Principe Pio, where the Egyptian Templo de Debod stands, and the Alcazar de Toledo, some 45 miles outside of Madrid.

Military Barracks of La Montana de Principe Pio (La Cuartel de la Montana)

La Montana de Principe Pio is a hill in Madrid where La Cuartel de la Montana, a 19th-century military barracks used to stand until its demolition after the Spanish Civil War. The site of the barracks holds a symbolic significance for Madrid as the place where Spanish fighters in the Spanish War of Independence were executed by Napoleon’s soldiers in 1808, as it was famously depicted in Francisco de Goya’s painting, The 3rd of May 1808. The military barracks were built in 1860 following the Carlist Wars close to the Royal Palace.2 In 1936, the barracks were the site of yet another iconic uprising that propelled the Spanish Civil War in Madrid. A group of rebel Nationalist officers opposed to the Republican government sieged the barracks with a plan to march out, but their coup d’état ended after a bloody confrontation with Republican militias.

Figure 4. The 3rd of May 1808 in Madrid, or “The Executions,” Francisco de Goya, 1814. Image from: www.museodelprado.es

As the barracks lay in ruins, both the Republican government during the war and the Franco regime after the war targeted the site for ambitious and representative projects that sought to communicate their interpretation of the events of July 1936 and post-war Madrid. For the Republicans, the barracks were the site of heroic Madrilenian resistance against fascism and for the Nationalists, it was the place of the first dissenting voices. The government of the Spanish Republic had set up a reconstruction committee for the planning of post-war Madrid and the plan included a new parliament building on the site of the barracks.

After Franco won the war, a new architectural style and planning were required to mark the ideological and political shift in Spain. Similar to Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, the architectural style advanced by the Falangist Party were the grand and monumental architecture of 17th-century Madrid that aligned a New Spain with the imperial Hapsburg dynasty. The planning scheme included a proposal to build the headquarters of the Falange party on top of the former barracks. In the end, the grand reconstruction project never materialized. According to Olivia Munoz-Rojas, Franco wanted to distance himself from the fascist governments of Hitler and Mussolini who expressed their ideologies through monumental architectural projects. In addition, Spain was struggling economically after the Civil War, which led to the abandonment of these grand plans. The site eventually became a public space and the chosen location to exhibit the Templo de Debod, a gift from the Egyptian government in 1968. The site joins Parque del Oeste to the north, where the frontline during the Spanish Civil War passed through.

Figure 5–7. Templo de Debod and surrounding park in Madrid.

Strolling in the park today, it’s difficult to imagine that one of the bloodiest confrontations of the war in Madrid took place there. The only physical traces that are seen in the northern side of the park are derelict remains of bunkers, nestled between the trees, with no sign or plaque explaining what they are or the charged historical legacy of this site. In Madrid, the legacy of the Spanish Civil War is well buried and curated by years of Franco’s dictatorship.

Figures 8–15. Bunkers from the Spanish Civil War in Parque del Oeste.

Figure 16–17. Bullet holes on a statue of Federico Rubio in Parque del Oeste.

The Alcazar of Toledo

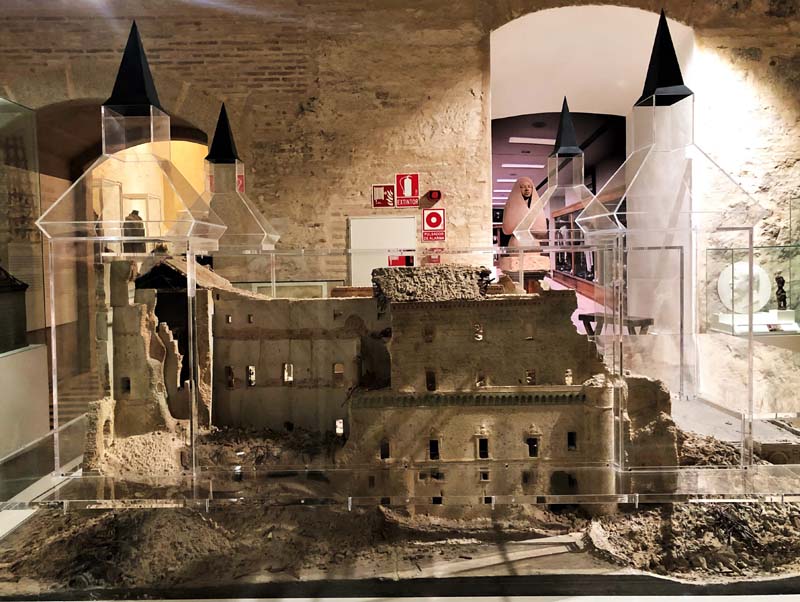

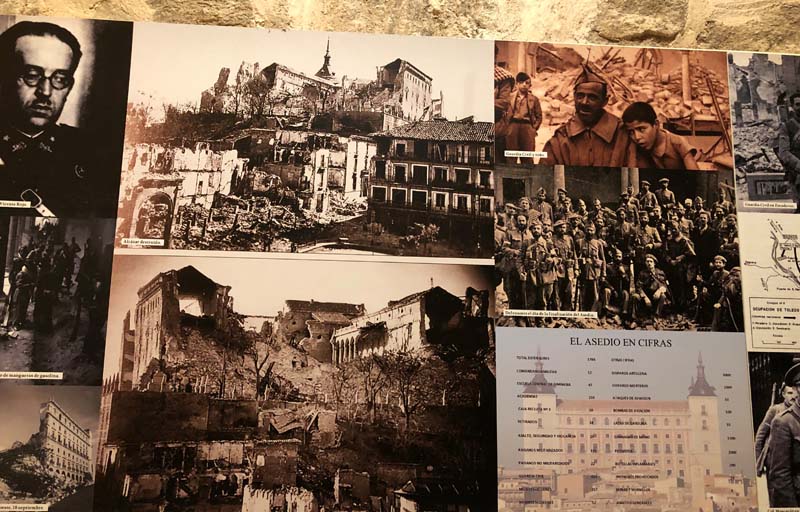

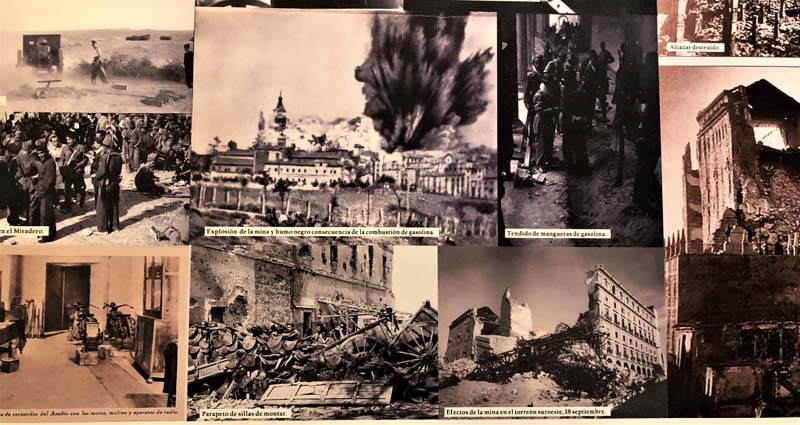

From Madrid, I took the train to Toledo, about 35 minutes. Toledo is a popular tourist destination for its preserved medieval layout and rich architectural legacy that includes a Gothic cathedral, a mosque from the 10th century, synagogues and the towering fortress, the Alcazar of Toledo, where the Toledo Army Museum is located. During the Spanish Civil War, the Alcazar of Toledo became another symbolic site in an ideological war. Between July and September 1936, Nationalists and right-wing groups and their families occupied the fortress and fought against the Republican forces as they bombed and destroyed most of the building. The battle to win the Alcazar was driven by its charged symbolic value rather than the need for territorial control. The fortress that dominates Toledo’s views was the royal residence of Spanish kings for centuries after they re-captured the town from the Moors in 1085.3 Before the 1936 siege, the fortress housed the Military Academy in Toledo. For the Nationalists, the Alcazar of Toledo is an icon of Spanish imperial history that cannot be lost to the Republicans. The extensive damage to the fortress can be seen in one of the Army Museum’s small rooms where a miniature model shows the Alcazar in its original state (plexiglass) and ruined state after the siege of Alcazar.

Figure 18–21. Views of the Alcazar of Toledo and its surroundings

The post-war story of the Alcazar of Toledo shows how architecture can be utilized to control the narrative of a place or the retelling of its history by those in power. After Franco won the war, the fortress was left in ruins and its image was disseminated and used in propaganda material as a memorial to the Nationalist victory.4 The restoration of the building started in 1950, many years after the war ended. Franco paid special attention to the reconstruction of the fortress establishing it as a tourist destination that celebrated Spanish victories, most importantly of which is the patriotic display of courage by the Nationalist rebels during the Siege of Alcazar.5 By turning the Alcazar to a commemorative space for his own conquest of Toledo, Franco aligned himself with Spain’s imperial rulers, strengthening his image as protector of Spain and further legitimizing the dictatorship.

Figure 22–26. Views from inside the Alcazar of Toledo.

Inside the Army Museum at the Alcazar of Toledo, I walked through many rooms that displayed weapons, apparel, miniature models of battles, and objects that celebrated the greatness of the Spanish Empire and its colonial reach. At some point, I was confronted with a crypt that contains the remains of Nationalist soldiers that died during the Siege of Alcazar, but I couldn’t find an exhibit that discussed the iconic event that led to the total destruction of the fortress during one of the most contentious episodes of the Spanish Civil War. I was surprised to find that critical history of the building was confined to one small room on the periphery of the museum floor under the name "The History of the Alcazar." When the Army Museum announced it would move from Madrid to the Alcazar of Toledo in 2003, it caused controversy that the collection would be housed in a famously Francoist icon.

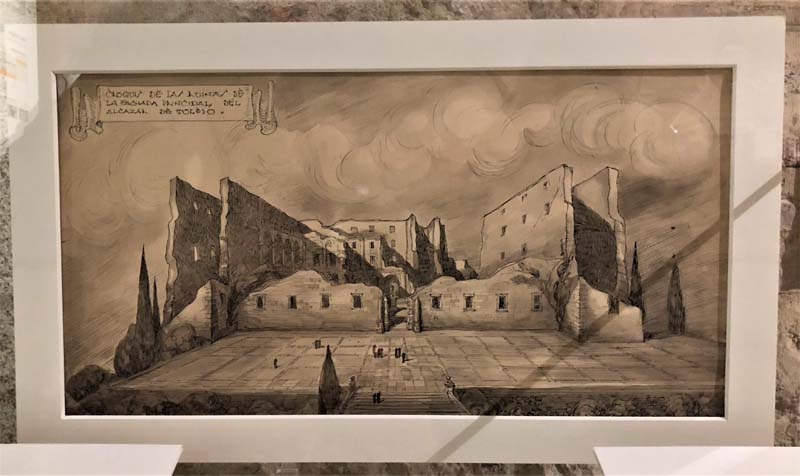

Figures 27–32. Model shows the damaged Alcazar of Toledo after the siege of the building during the Spanish Civil War. The glass containing the ruins represents the original building before destruction. Photos were taken at the Army Museum housed in the Alcazar of Toledo.

Figures 33–36. Representations and photographs from newspapers reporting on the damage of the Alcazar of Toledo. Photos were taken at the Army Museum housed in the Alcazar of Toledo.

Traveling to the Alcazar of Toledo cemented my understanding that the historical memory of the Spanish Civil War is still fighting to break from the controlled rhetoric molded by years of the Franco dictatorship. Spain is still unsure of how to treat its historical monuments that were built after the war and until Franco’s death or re-tell the story of Spanish Civil War from a different point of view in fear of opening past wounds, which means a lot of scars that were inflicted by the winning side remain hidden and unaddressed. My experience in Madrid re-contextualized my view of Berlin and its incessant struggle to understand and come to terms with its memorials and architectural legacy from the Nazi era and World War II. What is Spain going to do to face its past?

References

1 Bordes, Enrique, and Sobrón Luis de. Madrid Bombardeado: Cartografía De La destrucción, 1936-1939. Cátedra, 2021.

2 Muñoz-Rojas Olivia. Ashes and Granite: Destruction and Reconstruction in the Spanish Civil War and Its Aftermath. Eastbourne: Sussex Academic Press, 2011.

3 Raychaudhuri, Anindya. The Spanish Civil War: Exhuming a Buried Past. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2013.

4 Aronsson, Peter, and Gabriella Elgenius. National Museums and Nation-Building in Europe, 1750-2010: Mobilization and Legitimacy, Continuity and Change. London: Routledge, 2017.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top