-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Resistance and Urban Resilience in Barcelona

Sundus Al-Bayati is the 2019 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

Barcelona has been punished throughout history for being the capital of the autonomous Catalan community. Even the city’s urban form reflects a historical Catalan struggle for independence. After the end of the War of Spanish Succession (1701–1714), a neighborhood in Barcelona was flattened in retaliation for resisting the Franco-Spanish forces. Architecture is often used as an instrument of power, and especially during war, to showcase territorial control or mark a political shift. But the story of Barcelona’s urban transformation is not limited to a history of political and social subjugation. On the contrary, Barcelona’s development shows a city that has always been resilient and intentionally planned. I was searching for the traces of the Spanish Civil War in Barcelona, but I found myself as interested in earlier conflicts whose effects contributed to how the city developed across centuries.

From a Citadel to a City Park

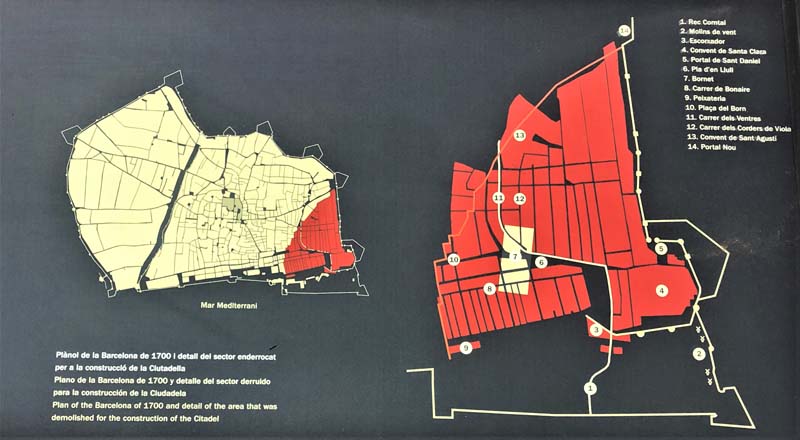

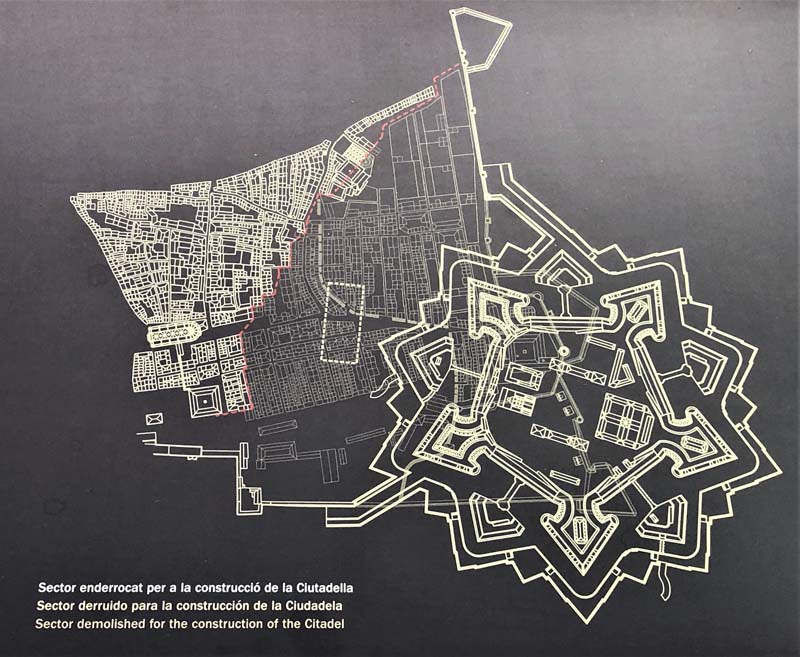

Only a small part of the medieval working-class district of La Ribera exists today in Barcelona. The district was razed after the defeat and capture of Catalonia by the Bourbons in the War of the Spanish Succession in 1714. The destruction of the district was not a casualty of war. The residential neighborhood was devoid of any military defensive structures. The demolition was ordered by Philip V after the war ended to punish the city and to clear a space for the construction of a new Ciutadella (citadel). The fortress stood at the current location of Parc de la Ciutadella for more than a century before it was demolished. However, lost parts of the Ribera district can be seen in Barcelona today. In 2013, archeological ruins from the medieval Ribera neighborhood were discovered during excavations beneath a 19th-century cast iron market, Mercat del Born. The excavations were part of a project to build the Provisional Library of Barcelona inside the market. After the discovery, the library project was relocated and the market was transformed to a cultural center to preserve and display an important recovered piece of the Catalan’s past.

Figure 1–4, El Born Culture and Memory Center (CCM), Barcelona

Figure 5–6, Plans of the destroyed Ribera district and the citadel that replaced it. Image from CCM, Barcelona.

Not far from Mercat del Born, stands one of Barcelona’s main attractions, Parc de la Ciutadella, with its monumental fountain, Font de la Cascada. The park is a microcosm of Barcelona’s urban history since the 18th century. This was the site of the great citadel ordered by Philip V after the demolition of the Ribera neighborhood. The fortress, which was the largest in Europe in its time, was constructed to ensure greater control of Barcelona should a rebellion arise against the King. With the exception of Barceloneta, an area that developed outside the medieval city walls to compensate for the need for housing caused by the demolition of La Ribera neighborhood, Barcelona’s growth was limited inside these walls.1 For over a century, the Ciutadella stood as a symbol of control and subjugation of the Catalan city by the Spanish absolutist government and was thus hated by its residents.

Figure 7, Font de la Cascaada, Parc de la Ciutadella, Barcelona

Figure 8–10, Parc de la Ciutadella, Barcelona

The fortress was destroyed in the mid-19th century and the rest was turned over to the city council. The site was transformed to a public city park as part of the first comprehensive urban reform in Barcelona, the “Extension” plan by IIdefons Cerda in 1859. The development of the park was further incorporated in the urban transformation of Barcelona when it was selected to host the 1888 Universal Exposition.2 From a symbol of Spanish control and subjugation, the site of the former Ciutadella became the soil for a flowering of Catalan industrial and architectural innovation and expression. One of the most prominent buildings of the Exposition, still in the park today, the Castle of Three Dragons, designed by Lluís Domènech i Montaner, is an example of Modernisme, a sort of Catalan Art Nouveau, whose most famous practitioner was Antoni Gaudi. Not all the buildings within the old Ciutadella were lost. The current Catalan Parliament sits inside an 18th-century arsenal building that belonged to the citadel, in the place where arms were kept to defend against a Catalan rebellion.

Figure 11–12, The Castle of Three Dragons, Parc de la Ciutadella, Barcelona

Figure 13, The Catalan Parliament Building, Parc de la Ciutadella, Barcelona

Bunkers, Street Fighting and George Orwell

When I arrived at my Barcelona rental, one of the first recommendations I received from my landlord was to check out the Carmel Bunkers at the Turo de la Rovira nearby. It has one of the best views of the city, she said. The hill was a strategic location for an anti-aircraft battery structure that went up in 1937, a time where a lot of bunkers were built quickly in Barcelona to shelter residents from the aerial bombs dropped by Franco’s Fascist allies during the Spanish Civil War. I had only been a few hours in Barcelona and someone actually mentioned the Spanish Civil War. I could already begin to see the difference in how the cultural memory of the war is dealt with in Barcelona compared to my experience in Madrid. In general, I found Barcelona’s cultural institutions such as Montjuic Castle, el Born Culture, and Memory Center or the Carmel bunkers, to better confront the memory of the war.

Confronting the legacy of the Spanish Civil War in Barcelona might be less controversial than in Madrid. Barcelona is not the capital and was not on the front line during the war. After Franco’s victory, Madrid, especially, was to communicate, through its urban form and architectural language, the image of New Spain and its Falangist principles. Franco’s takeover of Madrid, a city that has resisted a two and half year siege against his forces so that it became an icon of anti-Fascism, was ideologically important. During the Francoist era, Barcelona was neglected. Franco’s totalitarian regime suppressed Catalan culture and nationalism in Barcelona. The Catalan language was forbidden in government institutions and in the media. Autonomous Catalan institutions were abolished. After Franco’s death and Spain’s transition into a democracy, Barcelona was able to begin restoring its Catalan identity, which meant an automatic denunciation of the policies and decisions made during the Spanish Civil War and the Franco dictatorship.

Figure 14–22, The Carmel Bunkers, Barcelona

From below, I could see the Carmel bunkers sticking out, covered in graffiti. The spot is popular among locals and tourists as a place to hang out or have a picnic and enjoy the expansive views of the city. After the war, a large number of informal settlements emerged in Barcelona due to the lack of housing and the disused anti-aircraft battery became the home of Els Canons shanty town until 1990. From 2011, Museu D’historia De Barcelona (Barcelona History Museum) has transformed the structure into a heritage site with indoor and outdoor exhibition spaces that walk through the history of the bunkers.

After a week in Barcelona, I went on a Spanish Civil War tour led by a British historian named Nick Lloyd. The tour walks through sites in the Gothic Quarter, Placa de Catalunya, and the Rambla, where significant events and fighting took place during the years 1936–1939. When Nick asked us why we were interested in such a tour, few people had a similar reaction, that they have been in Spain for a while or multiple times and they haven’t heard Spaniards discuss the Spanish Civil War much. The beginning of the tour addressed the revolutionary and anarchist beginnings of the war in Barcelona and buildings that had become iconic during the conflict, like the Telephone Exchange building, where the clashes of the May Events started.

The May Events or the May Days refer to the five days in May 1937, where deadly clashes took place between the different parties and militias of the Republican side in the streets of Barcelona. The confrontation started when the Assault Guards, sent by the Republican government to take over the Telephone Exchange building that was controlled by the working-class anarchist CNT group. In Homage to Catalonia, George Orwell, who came to Barcelona in 1936 to fight in the Spanish Civil War against Fascism and was on guard in one of the POUM-controlled buildings during the May Days, describes this bloody and complicated confrontation. His account shows how the city was transformed into a battleground and its streets and buildings were divided among the different political factions:

“What the devil was happening, who was fighting whom and who was winning, was at first very difficult to discover. The people of Barcelona are so used to street fighting and so familiar with the local geography that they knew by a kind of instinct which political party will hold which streets and which buildings. A foreigner is at a hopeless disadvantage. Looking out from the observatory, I could grasp that the Ramblas, which is one of the principal streets of the town, formed a dividing line. To the right of the Ramblas the working class quarters were solidly Anarchist; to the left a confused fight was going on among the tortuous by-streets, but on that side the PSUC and the Assault Guards were more or less in control. Up at our end of the Ramblas, round the Palaza de Cataluna, the position was so complicated that it would have been quite unintelligible if every building hadn’t flown a party flag.”3

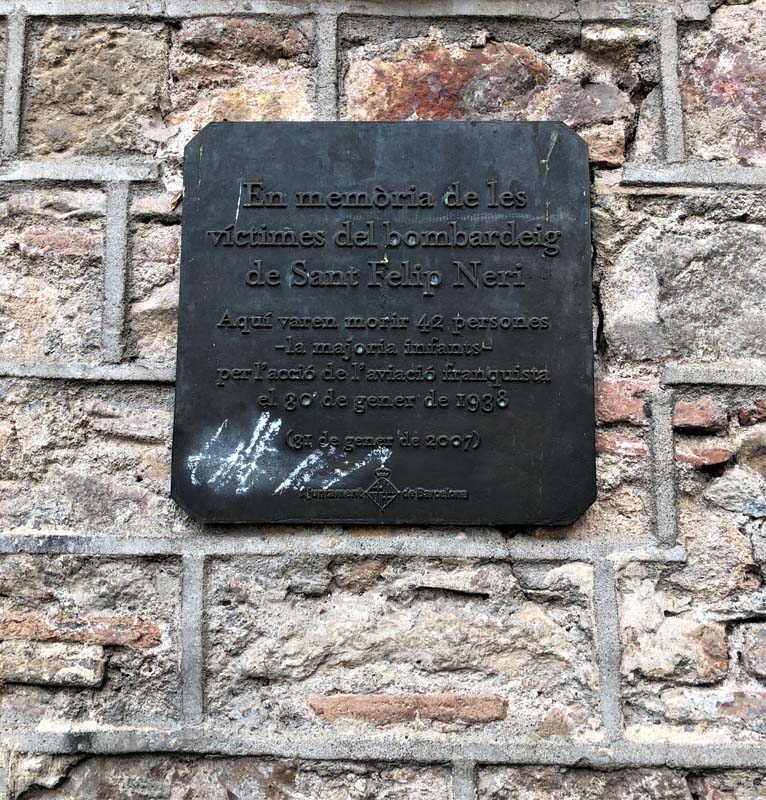

Towards the end of the tour, we stopped at the church of Sant Felip Neri. The façade of the church carries the scars of the war. Attached to the church is a convent where children sheltered from the bombardment by Franco’s air force on January 30, 1938. On that date, bombs fell on the square, damaging the whole building and killing 42 people, most of them children. During the Franco dictatorship, a different story was told about the events that took place in Sant Felip Neri square. According to Francoist propaganda, the marks on the façade were caused by bullets from anarchist executions of church priests. Today, next to the scarred façade, a black plaque reads: “In memory of the victims of the bombing of Sant Felip Neri. 42 people died here - most of them children due to the action of Franco's air force on January 30, 1938.”

Figure 23–26, Church of Sant Felip Neri, Barcelona

Unearthing a Roman Past

Barcelona’s urban development was stunted under Franco, with the exception of one prominent project, the opening of the Avinguda de la Catedral (Cathedral Avenue) in front of the Barcelona Cathedral. In the map of Barcelona, it is one of the wide avenues that carves through the historical urban fabric, right next to the Gothic quarter. The project wasn’t envisioned by Franco’s government. The opening of the Cathedral Avenue was first proposed in Cerida’s renowned urban plan for Barcelona in 1859. Since then, it had been proposed and approved in multiple urban reforms. In each plan, the objectives were sanitation, improved circulation, and better views of the Cathedral. Critics of this urban intervention feared the loss of centuries-old residential and mercantile buildings and the network of narrow streets that gave the area a unique historical character. The bombs dropped by Franco’s air force during the Spanish Civil War flattened a lot of buildings that stood in the way of opening up the Cathedral Avenue.4 So when the war was over, the project resumed as planned. Franco’s interest in the project grew bigger for its economic potential and ideological implications for his regime when Roman ruins, discovered in the early 20th century, took a central importance.

Figure 27, Cathedral of Barcelona

Figure 28–30, Views of the Cathedral Avenue, Barcelona

In front of the Gothic Cathedral of Barcelona stood the Roman city wall that marked the northwestern edge of Barcino (Barcelona’s ancient name). In the early 20th century, sections of the walls that ran along Tapineria Street were discovered and their restoration and disclosure were completed in 1953.5 Although the area’s architectural legacy encompasses many historical periods, its Roman one was highlighted and selected for restoration by the new government. The revelation of Barcelona’s Roman past was a fitting message for the regime’s Falangist identity that liked to align itself with the Roman and Hapsburg Empires. The excavations continued following the path of the Roman wall adjacent to the Cathedral towards Placa Nova where two Roman towers mark the city’s gate. Further destruction of the old houses in between the towers revealed an ancient military belt, which formed the northwestern edge of the Roman settlement.6 Not only did the project destroy whatever stood in its way to expose the Roman ruins, a non-surviving arch that was part of the aqueduct that carried water to Barcino was recreated next to one of the towers.

Figures 31–33, Barcino’s Roman walls and the two towers that formed the city’s gate

Figure 34, A reconstruction of a section of the aqueduct that carried water to the old city of Barcino

References

1Maclean, Robert. “Barcelona: A Case of Urban Palingenesis” In La Città Nuova: Proceedings of the 1999 ACSA International Conference, 29 May-2 June 1999, Rome, edited by Katrina Deines and Kay Bea Jones. Washington, DC: ACSA Press, 1999.

2 Ibid.

3 Orwell, George. Homage to Catalonia, 117. London: Penguin, 1989.

4 Muñoz-Rojas Oscarsson, Olivia. “Archaeology, Nostalgia, and Tourism in Post–Civil War Barcelona (1939-1959).” Journal of Urban History 39, no. 3 (2012): 478–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144212443709.

5 Ibid

6 Ibid

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top