-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Layers of Meaning: Barcelona and Beyond

Anne Delano Steinert is a recipient of the 2022 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

The first chapter of John Stilgoe’s Outside Lies Magic, aptly named “Beginnings,” lays down some rules for observing the world in meaningful ways. The goal is to generate inquiry, to find questions rather than answers. The goal is wonder.1 The first one of Stilgoe’s rules is to slow down. The second is to put down all technology. I have been assigning this chapter to classes of high school and college students for more than twenty years, and yet I don’t often make the time to follow Stilgoe’s rules. Hold into this thought. I will get back to John Stilgoe in a minute.

One of the goals of my Brooks Fellowship is to explore the ways ordinary people make meaning of the built environment. This quest emerged from historic preservation struggles I have witnessed lately in my hometown of Cincinnati, Ohio. In Cincinnati we have lost several buildings recently which, to my mind, were significant monuments to the city’s multi-layered history. The one I had the most to do with was Revelation Baptist Church, which was built as a synagogue in 1865 and, according to a notably non-scholarly website that tallies such things, would have been the tenth oldest purpose-built synagogue in the country at the time of its demolition in May 2020.2 It was also the church where Civil Rights leader Fred Shuttlesworth was pastor during the most successful period of his activism. The building was demolished by the owners of a new Major League Soccer stadium nearby. They thought they might someday build something on the now vacant site.

Figure 1: Revelation Baptist Church, formerly John Street Temple, built in 1865 in Cincinnati Ohio. Demolished in May 2020.

In addition to recent losses, Cincinnati is also struggling with the stewardship of the Terrace Plaza Hotel designed by SOM (Gordon Bunshaft and Natalie DuBlois) in 1948, which was recently denied landmarking by our planning commission. If you want to learn more about the amazing Terrace Plaza, check out the article about it in the February 3, 2021, Architectural Digest by Laura Itzkowitz (available online) or check out the excellent original black and white photos available on SOM’s website.

What I have witnessed in most of these cases is that few citizens and fewer people in power understand the value in these buildings. I believe (though this may be naïve) that if more people understood why these buildings matter, then more of them would be saved.

This brings me to thinking about how people understand the built world. How does the everyday passerby learn the value of a place? A building might have historical/cultural value and/or it might have artistic/architectural value. People probably need different ways to understand these two different measures. What I am thinking about on this trip is how people read buildings to understand or assess their value and what interventions or interpretive aids help build this skill. Buildings of artistic and architectural merit are probably easier to interpret because you can see that there is something special about them. The spark for this blog post came from a seemingly ordinary building, which led me to lots of questions, and then some answers, and then more questions. I hope you’ll enjoy the ride.

Returning to John Stilgoe, I left on this trip on May 25 and had been going non-stop ever since. We arrived in Paris and, after wrestling with some jetlag, hit the ground running. I feel like I have been moving ever since. I want to see everything, so I have been dashing around to take it all in. I have been taking lots of photos. I have even been relying on Google Maps to tell me where to go. What I haven’t been doing is slowing down and putting down my technology.

I am incredibly grateful to the fellowship committee, because I recognize that my application was a little unusual. I am a single mom, and there wasn’t really any way for me to do the Brooks Fellowship without bringing my eleven-year-old along. Bringing him with me also meant I would need a babysitter to care for him while I was looking at and thinking about architecture. The Brooks committee understood this and were willing to accept a proposal for all three of us to travel. We are staying with friends and family or in other low-cost lodging and using Eurail passes to stretch the budget. All of this is to say that I’ve got an eleven-year-old and an eighteen-year-old along on this trip—and oh-boy do they like technology. One night in Barcelona I returned to our humble and crowded hotel room, dead phone in hand, to find them watching Pirates of the Caribbean Three on the computer. It was loud and took up all the “space” in the room, so I went out for a walk. In my exile I found myself sitting in a small plaza near our hotel just looking at the seemingly ordinary building that happened to be directly in front of the bench I had chosen on Carrer De Las Ramelleres. As I felt the rush of the day drain out of me, completely liberated from my phone, now home on the charger, I gave myself over to “reading” the building.

I am going to briefly articulate the process I went through. For some readers this will probably seem overly simplified or a statement of the obvious. I am doing it because I think it is important for architectural historians to “show our work” and be clear on how we get from one idea to the next. If we want people who are not trained as architectural historians to appreciate buildings and help save them from demolition, it is important to make our processes and values transparent and user-friendly.

Figure 2: The door to Casa de Misericordia, Barcelona, Spain

I was drawn to the building by a mysterious incongruity between a historic door surround and a fresh plaster façade. The door gives the sense of a buried past popping out from a modern façade. The door has a triangular pediment topping an entablature held up by two simple engaged pilasters. On the slope of the pediment are stone orbs held up on little feet. All of this is beat up—pock marked, chipped, and discolored. The battered stone doorway has been left exposed, but the rest of building around it has all been plastered over, presumably to clean up a façade as down on its luck as the doorway (the building’s simple window lintels and surrounds were also left exposed). Today a sign on the modern glass door reads, “Casa de Misericordia.”

Once I took in the general shape of the doorway, I began to see the finer details. I noticed a faint shadow of something painted above the doorway. It reads “Casa D Infants Orfens.” Ah-ha! It was an orphanage!

Figure 3: Close up of ghost of painted sign above the door.

This squares with another detail—inside the triangle of the pediment is a carved Catalan crest. The crest leads me to believe that from the time the doorway was carved it appears to have been an official or institutional building. It was at some point used as an orphanage, but that could have been a later use, because the sign I read was painted onto the façade rather than being carved in. As I stand up and go closer, I see that there is more carving of the two sides. It says “I.S.” on one side and “78” on the other. It is as I turn away from the doorway that I notice the most amazing piece of the puzzle, but I am going to provide a little more of the building’s general layout and details before I reveal my big find.

The building is three stories high. The masonry façade is mostly solid, so there are big spaces between the relatively small window openings. It is nine bays wide, but the façade curves out slightly after the fourth bay. The door I’ve been describing is located at the second bay from the left which was (and is) clearly the formal entrance to the building. This entrance faces onto a public plaza (Placa de Vicenc Martorell) with benches and a playground. The building has doors at the street level in the first six bays, though the major entrance is the one I’ve described at the second bay. The others now sport roll-down gates covering shop windows at night. One is a great bookstore. Above these doors are small horizonal windows covered in a grid of heavy iron bars. I wonder who they wanted to keep in or out. Were the kids trying to escape from the orphanage? Or did they need protection? There is a rust-streaked carved plaque over another door, with a date of 1790, commemorating the construction of some part of the hospital (see figure 7).

Figure 4: View of the entire Carrer De Las Ramelleres Street façade of Casa de Misericordia

Figure 5: Building from a distance showing its location on a busy plaza and playground. Note the door surround pictured above and the small round opening at the door to the right of the main door.

I notice lots of other details, but I’ll spare you. Some pieces I can make sense of right away and others I will push to the side. I experience this process like dumping out the pieces of a new jigsaw puzzle. At first you’re not sure where your focus should go. Should you sort them by color? Should you find the faces? Here I just observe all the parts of the building and try to figure out how to make meaning of the puzzle.

Figure 6: Close up of the façade with details.

Figure 7: Dated plaque above a door in the third bay. Raquel Lacuesta Contreras’ article notes that this plaque has been moved from its original location on the ground floor to a perplexing location at the second story.

So now, back to my ah-ha moment at the door. As I turned away from the carving over the door, a round opening in the façade caught the corner of my eye. It was a round hole, maybe a foot in diameter, with a wooden frame and filled in with a slightly bowed board. Above it to the left is a small donation slot.

Figure 8: Round opening and donation slot

I knew instantly what this was, but only because I had some very specific knowledge acquired through my dissertation research. I wrote a chapter that highlighted the desperation of unwed and poor pregnant women in the time before sexual liberation and pasteurized milk. From this research I knew that eighteenth- and nineteenth-century orphanages in Paris and London had included windows (sometimes called foundling wheels) where desperate women could leave their babies anonymously in a wall of the orphanage. It had never occurred to me that a building with this baby port might still exist, but there it was, right in front of me. And I knew right away that’s what it was. As I looked around a little stunned by this discovery, I saw that there was, nearby, a graffiti-covered interpretive panel with information and photos about the little hole.

Figure 9: Text of the interpretive panel

Figure 10: Side view of the interpretive panel covered in graffiti

This panel had been put up to try to teach the public about the importance of this strange feature of the building’s façade. I read the panel and it confirmed that yes, this little porthole had been a baby abandonment drop-off station for desperate women. Suddenly this building transformed for me into a monument to the struggles and difficult choices of generations of women.

The English-language side of the panel says this was the “Provincial House of Maternity and Foundlings of Barcelona,” and explains that industrialization resulted in the arrival of many poor single women from the countryside who had come to Barcelona seeking work and that at the same time the rate of “illegitimate” births increased “exponentially.” The sign doesn’t make the connection between the powerlessness of these poor women and the rise in pregnancy in unmarried women, but clearly their poverty and lack of support networks put them in a position where they could be easily taken advantage of. The panel goes on to say that the social stigma of the day resulted in abandonment of many children to the care of charitable institutions. It then reads, “the foundling wheel in this wall, where newborn babies could be left, represents a host of dramas and injustices. On top of the stigma, mothers faced the pain of abandonment.” It goes on to note that, “most infants died before their first birthday,” and to explain that those who survived were transferred to another orphanage where boys would be trained “to be shopkeepers” and girls would be “trained for domestic service.” The panel also includes three photos, one of a room with both a bed and a crib, and another of rows of kneeling children in prayer.

What I learned in writing my dissertation is that as single women flooded into newly industrialized cities to find work, they often worked as live-in domestic servants. In this circumstance they were in constant and potentially close contact with their employer—a person with significant power over them. It would have been difficult to refuse physical contact. Alternately, these women might just have been lonely and in need of human connection. If, by these or any other circumstances, an unmarried women found herself with child, she was stuck. If the pregnancy became known, no one would marry her. If she tried to raise the child alone, it would be nearly impossible to find work. In an age before pasteurized milk, the only way to feed a baby was with breast milk. How could a mother work to earn money and nurse her new baby? She could not possibly afford a wetnurse.

I write this blog post just days after Roe v. Wade, which guaranteed women privacy to make their own reproductive decisions, has been overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court. I fear we are about to return to an era of very difficult choices for many women. A few weeks before I left for my fellowship trip, a draft of the Supreme Court decision was leaked, and I was interviewed about my dissertation chapter by Cincinnati’s local NPR station. My work was included in a story about what life was like for women in Cincinnati before legal abortion. You can read that story here. This building suddenly feels even more relevant as a document of the impossible choices unmarried pregnant women had to make.

The little baby port in the building has clearly survived many changes to the building. It remains today as a powerful document of this building’s role in the lives of hundreds or thousands of women and babies over possibly hundreds of years. The interpretive panel exists to explain this history to the public so they will appreciate this building’s past. Yet, as I looked around at the graffiti on the panel and even on the little wooden door itself, I watched hundreds of tourists stroll by without even a glance. Even this totally intact clue to this building’s history, clearly marked with an informational panel, even if a somewhat abused one, does not catch people’s notice or communicate its significance.

Figure 11: Graffiti on the foundling wheel

At one point I debated about going inside the government office to ask if they knew anything about the history of this building or if I could see the inside of the foundling wheel, but I decided I didn’t want to go into a building with a police officer stationed in the lobby to ask crazy questions in a foreign language. A few days later I did ask the cashier at the bookstore. She told me that she thought the building had been a convent and that there was a crypt underneath.

Here I should note that the bookstore (called La Central) also complicated my understanding of this building. When I entered the bookstore it was into a small room, but that small space opened into a larger one and then a series of small little cells, a coffee bar, and even a courtyard with a restaurant. There were at least three different ways out on three different streets. It was a bit of a maze and I have to admit I got turned around in there more than once.

With all these clues and questions, I turned to written resources I could find on the internet. There were several blog posts about the foundling wheel, but most useful was an article (a report really) published in 1992 in a Spanish-language publication called Espacio, Tiempo y Forma (Space, Time and Form) by Raquel Laquesta Contraras. The article is entitled “La Casa municipal de Misericordia de Barcelona. Historia de su evolución arquitectónica” or “The Municipal House of Mercy of Barcelona. History of its Architectural Evolution.” I don’t read Spanish, so I read the article by pasting it into a word document and using Google Translate. It wasn’t a perfect translation, but I could get the idea. The article is sixty-two pages long, so just to summarize I learned that this building was part of a larger complex occupying a significant portion of a large city block. It had been founded by a man named Diego Perez de Valdivia as a house of mercy for the poor in 1581. The first building bears a date of 1603, but most of the current buildings date to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The façade I have been exploring on Ramelleres Street was added to the complex in 1788, probably designed by Rafael de Llinas and P. Modolell. The House of Maternity and Foundlings was officially added to the complex in 1852, “occupying the east wing of the building, which overlooks the street of Ramelleres,” though the complex had been serving young women prior to this official designation.3 The complex held a diverse array of uses including a convent with chapels, courtyards, and orchards. The article makes one perplexing note that, “the [historical] documents mention the existence of some dungeons.” I hope the use of the word “dungeon” is just a translation error! The complex was bombed twice, first by the regent of Spain’s young queen in the 1840s and again in 1938 during the Spanish Civil War, which helps to explain the pock marks on the door. It has been subject to multiple renovations and reconstructions over 500 years. I was able to get some of this by observation, but it was comforting to have the written records confirm my hypotheses. But this step of moving from questions to the documents with comforting answers is something most people won’t be able to do. How does this impact their connection to historic architecture?

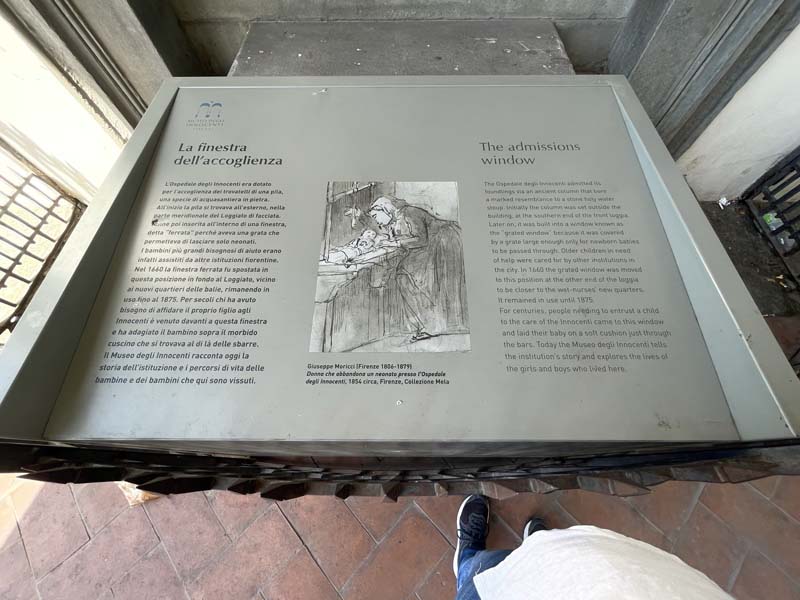

After writing most of this post, I stopped off in Florence for a day. I remembered that the Ospedale degli Innocenti (Hospital of the Innocents)—paid for by Florence’s silk merchants and designed by Filippo Brunelleschi beginning in 1419—had once also included a baby portal, so I went there to check it out.

Figure 12: View of Ospedale degli Innocenti, designed by Brunelleschi, Florence, Italy. Note the foundling window to the far left at the top of the steps.

What I found was a window covered with thick metal bars at the top of a staircase on a main square. Here there was also an interpretive panel. It taught me that the bars allowed only very small newborns to be passed through and that they could be laid on a velvet pillow inside the window where a nun slept on a cot ready to care for any deposits. I am a little skeptical about this panel because I know for sure that my almost 9-pound baby would not have fit through those bars.

Figure 13: Close-up of the window

Figure 14: Interpretive text panel

As a side note, this building is also famous for the blue and white glazed terra cotta rondels sculpted by Andrea della Robbia and added to the building in 1487. Each rondel features a swaddled baby. In only one the baby’s bindings are falling away, illustrating the potential (and unfavorable odds) for babies at the hospital to be liberated. The opulence of this circumstance contrasted the austerity of the building in Barcelona, but the heartbreaking reality that women had to abandon their babies remained the same. I’m not sure the buildings themselves (even with interpretive panels) are doing such a great job of communicating this reality.

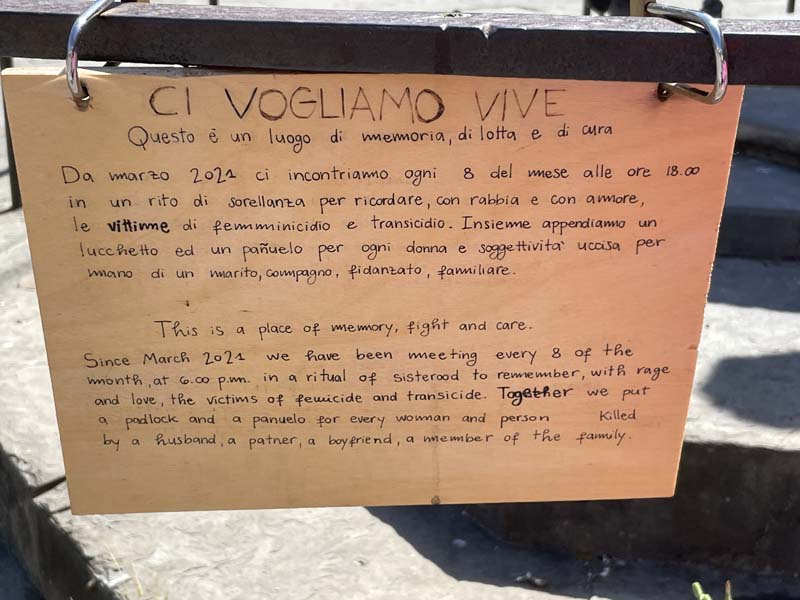

Just across the square from the hospital was a much more urgent and effective monument to a different kind of human suffering. This makeshift monument to murdered transgender people used in-your-face placement and bright colors to draw attention to itself. There is an urgency to this hand-written raggedy memorial drenched in the symbolism of locks and fuchsia fabric. Centuries old buildings and formal institutional text panels don’t have the same power, but I wonder if there isn’t something we could learn from this powerful and well-placed memorial.

.jpg?sfvrsn=2e13209b_5)

Figure 15: Transgender memorial in the Piazza della Santissima Annunziata in Florence in front of the Hospitale degli Innocenti

Figure 16: Text panel on the transgender memorial

I have just been reading Vince Michael’s “Diversity in Preservation: Rethinking Standards and Practices” in the spring 2014 issue of Preservation Forum. He quotes Raymond Rast saying that “for most people, buildings don’t ‘speak’ very coherently,” and that “the average person does not have the experience to ‘read’ a building or judge its integrity or even know whether it was built in 1830, or 1930 or 2009.” My experience with the Casa d’ Infant Orfens both proves and disproves this statement. I believe that the deep observation I did of the building is something anyone could have done. It generated a few answers (this was an orphanage at some point) but mostly questions. I think most people can use their eyes to look at buildings and generate questions. According to Michaels, Rast might say that I believe this because I am trained to read buildings and that I can’t not read them—just like once you know how to read you can no longer see words as just a string of shapes. My brain automatically gives meaning to the clues I see and starts to build a story from those clues. I disagree with this to some extent. I believe that people without my training can read buildings, and my years of teaching Stilgoe to students absolutely confirms this. Anyone can find the puzzle pieces if they look. But putting the puzzle pieces together is harder.

Making sense of the foundling wheel is something I could do because I had very specific background knowledge which most people wouldn’t have, although the interpretive panel on the site also made some of that information available to passersby if they take the time to read it. I also see that understanding the foundling wheel and the desperate circumstances of the unwed mothers made the building more meaningful to me. This context makes preserving this building more urgent in my mind. If the idea of preservation is that buildings educate us all about our shared past (rather than just those of us with specialized training or extra information), will it work if people lack the ability to read the story the building tells? How do we make sure the built world is legible to non-experts? How can we present information in meaningful ways to help the everyday viewer value buildings? This trip is all about that question, and I am already generating some answers, but you will need to wait for my next blog post to find out more about what I’m thinking.

1 If you haven’t read the first chapter of Outside Lies Magic, I cannot recommend it highly enough. You should read it. The book is sadly out of print, but there are plenty of used copies on the internet.

3 Raquel Laquesta Contraras, “La Casa municipal de Misericordia de Barcelona. Historia de su evolución arquitectónica” Espacio, Tiempo y Forma Serie V il, Hist. del Arte, t. V, 1992, 97-158. Note I used a Google Translate version of the Spanish text.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top