-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Curious Art Nouveau

Anne Delano Steinert is a recipient of the 2022 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

I am embarrassed to admit that before this trip I had no idea how much Art Nouveau architecture was in Prague. My education on Art Nouveau was all about Hector Guimard and Paris. Even when I learned about Alfons Mucha, it was his posters in Paris. I’m humbled by my own ignorance.

Walking through the center of Prague is like visiting an outdoor museum of the Art Nouveau (and Art Nouveau-adjacent forms of experimental and hybrid early modernism). Every turn seems to bring a new treasure into view.

Figure 1: Buildings like these at 11 and 13 Gorazdova štít are ubiquitous throughout Prague. It seems like every corner you turn reveals new Art Nouveau facades like these.

Figure 2: Upper-level details at Gorazdova štít 13.

Figure 3: Door detail at Gorazdova štít 11.

Figure 4: Corner detail at Gorazdova štít 11.

I was surprised by the way Art Nouveau details and ornament were freely mixed with other styles in Prague. Often Art Nouveau features were applied to more traditional façades, or they were combined with other elements that were more Art Deco.

Figure 5: Though this building at Masarykavo 8 has applied ornament at the door that I would call Art Nouveau, the overall façade is more complicated and favors geometrical forms which lean more toward Art Deco.

Figure 6: Door detail at Masarykavo 8.

I have long been drawn to Art Nouveau. I am taken with the graceful fluid organic forms of flowers, trees, and human bodies. I love the innovative uses of materials and the provocative sense of motion. Prague has all these things plus color. Buildings here are painted bright colors and they feature colorful mosaics, tile work, and frescos. Most of these buildings are five- to six-story apartment buildings and hotels with storefronts at the ground floor, but there are also more use-specific buildings like the main train station and the Prague Municipal House.

I did some research and learned that Art Nouveau architecture came to Prague in the late 1890s. There was a building boom in response to the 1893 law which called for the modernization of the old urban slums leading to mass demolition, especially in the old Jewish quarter. (It is worth noting here that this pattern of destroying the oldest and least modern homes housing citizens with the least resources for “urban renewal” is a pattern that repeats again and again in urban history, particularly in the destruction of African American neighborhoods across the United States in the 1950s and 60s). Newly vacant lands were redeveloped as housing for wealthier urbanites, a good deal of it built in the Art Nouveau style.1 The first known Art Nouveau design in Prague was the interior of the Café Corso designed by Friedrich Ohmann, professor at the Prague School of Applied Arts, in 1898.2 As in all cities, the Art Nouveau here was a reaction against the formality of nineteenth-century architectural styles and part of the beginning of the quest for a modern architectural expression of the complexities of the new urban industrialized landscape. As industrialization brought new wealth, new technologies, and new materials, it also brought crowded urban conditions and new ways of living in cities now connected by electric rail lines where large department stores displayed glittering piles of goods available to a new urban elite. The number of Art Nouveau hotels in Prague is an indicator that travel was also an important part of modern Prague. (Today’s Palace Hotel, Hotel Central, Hotel Grand Europa, and Hotel Meran are a few of them).

The adjacent hotels Grand Europa (originally Hotel Archduke Stephan) and Meran (originally Hotel Garni) on Wenceslas Square were given their Art Nouveau facades between 1903 and 1905. Sources differ about attribution but agree that Bedřich Bendelmayer was the primary designer.3 The buildings are currently undergoing a massive renovation (as you will see from the photo), so the interior was closed, but the exterior is fantastic.

Figure 7: The Hotel Europa and Hotel Meren on Wenceslas Square.

On one of my many walks through Prague, I happened across the Hlahol building designed by Josef Fanta and Čeněk Gergor and built between 1903 and 1906. The building was locked so I didn’t get to go inside to see the concert hall, which I learned later included paintings by Alfons Mucha, but the stunning exterior was enough to reminded me that architecture is really public art.

Figure 8: Hlahol at Masarykovo nábřeží 16 features Art Nouveau tile, metal, sculpture, and painted detail.

Figure 9: Hlahol building roofline detail.

Figure 10: Hlahol building door detail.

Figure 11: Hlahol building sculptural detail.

The Prague main train station, formally known as Franz Josef Station, was built between 1901 and 1909 and designed by Josef Fanta.4 The smaller original station has now been joined to a massive modern train station and shopping mall, making the original part of the station hard to find and photograph, but the original entrance rotunda is intact and well restored. I also stumbled upon an unrestored bit of the station in front of the baggage check room. This section includes a non-functioning clock flanked by two figures above the modern concourse. You can see from my photos that this guano-stained remnant of the original architecture stands out starkly against the blah interiors of the modern station.

Figure 12: Franz Josef Station rotunda.

Figure 13: Art Nouveau clock and sculpture visible from the lower level of the modernized station.

Figure 14: Clock detail. This clock is only right twice a day!

The Prague Municipal House is a total riot of color, pattern, and ornament encrusted on nearly every surface, almost to the point of absurdity. The multi-purpose building includes a café, two restaurants, a cavernous basement beer hall, formal presentation halls for the mayor and other dignitaries, offices, and a concert hall currently seating 1,259 with an entire floor of coat racks. Stylistically it is a hybrid. It has a baroque-inspired façade and concert hall with layer upon layer of Art Nouveau and distinctly Czech ornament. It was built between 1904 and 1912 on the site of the former Royal Court by Antonín Balšánek and Osvald Polívka.5 The applied ornament includes metal work, railings, mosaics, floor tile, upholstery, tapestries, clocks, stained glass, and paintings executed by a huge group of artists (including Alfons Mucha, who contributed paintings in the anteroom of the Mayor’s chamber). Sadly, the result of involving so many artists is a decorative program that doesn’t hold together very well. Each individual piece is beautiful and masterful, but as a whole, the building feels disjointed and disorganized, as the photos will show.

Figure 15: The Prague Municipal House exterior shows an explosive mix of styles.

Figure 16: Municipal House concert hall ceiling showing Baroque-inspired forms with Art Nouveau metal work and stained glass.

Figure 17: Municipal House stair hall view into the lower level showing multiple materials and decorative approaches.

Figure 18: Municipal House lower-level beer hall.

Figure 19: Municipal House second floor tapestry detail with a uniquely Czech stylistic approach.

Figure 20: Municipal house second floor metal ventilation grate.

Figure 21: Municipal Hall second floor ceiling panel painting by Alfons Mucha

I understand that Art Nouveau is not everyone’s favorite. I know many people find it garish and over-the-top or argue that it is nothing more that the application of a falsely innovative surface onto a traditional exterior, but I do think that my attraction to it illuminates a few things about how non-experts (which I definitely was in Prague!) perceive the world around them. This brings me back to the subject of my previous blog post. For folks who haven’t read that post, my premise was that if we want to preserve historic buildings, we need to make sure that they are valued, so we need to find ways to communicate their value beyond trained experts.

I have tried to explore every possible means available to ordinary folks who want to learn about the history of cities and architecture. I have visited urban history museums in Athens, Budapest, Marseille, Vienna, and Barcelona. I have taken public and private walking tours. I have read signs and plaques, looked at works of art, and climbed up to see views from tall towers. I have read guidebooks and listened to audio guides. (Thank you, Rick Steves). I went to light shows in Chartres and Rome, and I even checked out a virtual reality history program in Vienna called “Time Travel Magic Vienna History Tour,” then put on VR goggles to view a sister program called “Sisi’s Amazing Journey.” (They were both deeply troubling). I have taken boat rides and a bus tour and tried to take advantage of all the ways people might find to learn about cities. I have watched people interacting with the built environment, including my own child. A few patterns have emerged.

What I found is that using the built environment as a way to teach about the past is not about providing accurate factual information. Even where such information exists, very few people take advantage of it. While having the facts on hand is useful, the first and more important step is generating enough curiosity to get people to stop and look. You might know that Eleanor Roosevelt quote where she said, “I think, at a child's birth, if a mother could ask a fairy godmother to endow it with the most useful gift, that gift should be curiosity.” Of course, she was right. What I have observed is that if buildings, exhibits, signage, and the like can generate curiosity, then the observer will follow that curiosity to generate questions and then investigate the questions to get the answers they’re seeking. Having factual information or historic photos available in an exhibit makes the answers easy to find, but with the internet most people can instantly find answers just by typing in a few simple search terms.

So how do we generate curiosity? Well, first people have to look. Everywhere I have been folks are busy looking down at their cell phones rather than up at all the amazing architecture they are passing. Cell phones, much as they are handy to help us answer our questions, are a huge impediment to generating questions. If people are watching a TikTok or texting their bestie, the chance of noticing the Municipal House as they walk by goes way down. In my experience across Europe the three attributes most likely to generate a look up, and therefore curiosity, have been color, motion, and authentic immersion (these attributes clearly echo those that draw me to the Art Nouveau). I’m going to offer a few examples of each. Some overlap.

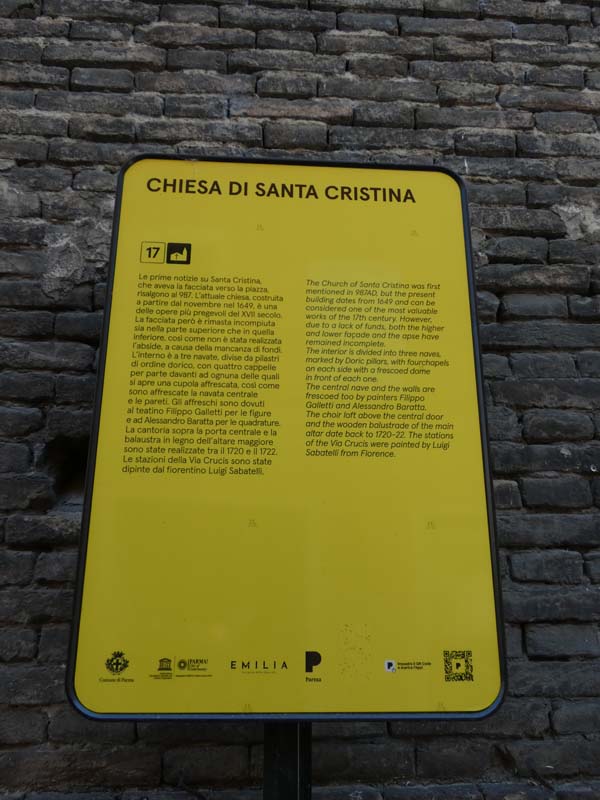

The best and simplest example of color as a tool for curiosity creation in the built environment were the historic markers in the city of Parma in Italy. They are bright yellow. The text is written in big letters and the sign is placed in an obvious spot next to an important landmark. These are the equivalent of our American “brown signs,” but they have color working in their favor. While neutral brown blends in and is easy to overlook, these bright yellow signs scream at you and tell you there is something important to notice.

Figure 22: Historic signage in Parma, Italy.

Color was also an important part of the nighttime light show in Chartres, but it added motion, too. This light show may have been the most engaging thing I’ve experienced on the whole trip. The show offered free projections on buildings throughout the town for two hours each night. Some of them were merely beautiful, but the projections onto Chartres Cathedral were also designed to spark interest in the history of the church. There was a classical music soundtrack playing and the projections mapped exactly onto the details of the building, calling out shapes and spaces visitors might have missed in the daylight. The show offered details from medieval construction methods and historical figures associated with the building. It didn’t offer much information about them, but it combined a few details with light, color, and sound in a way that generated curiosity, even in my eleven-year-old. The show raised the kinds of questions that would motivate many people would go home and google answers.

Figure 23: Chartres Cathedral light show using light to highlight architectural details.

My second nighttime light show was of Julius Caesar’s forum in Rome. This one was something visitors have to pay for and a reserve a time. Visitors use an audioguide set to their preferred language as they move to specific locations through a set path in the nighttime dark of the forum (with a human guide there to keep us moving along). The audio guide offered descriptions of specific sites as they lit up with light. It was like an immersive history lesson where I had a lecture in my ears and the pointer illuminating each piece of the talk as I walked past. Using light, the production was able to fill in missing pieces of the ruins or highlight the ways buildings had changed over time. Being immersed in the space made it easier to imagine life there. It was incredibly effective at both generating curiosity and providing accurate information. It added a reality and sense of connection, which is missing in the stark white ruins visitors see during the day.

Figure 24: Roman light show of Caesar’s forum uses a building exterior to project a historic interior cut-away view

Part of the advantage of using buildings to teach about the past is that interacting with architecture is an immersive and sensory experience. We move into buildings, feel their textures, see their colors, experience their volume. We hear how sound can be contorted by walls and openings. We experience the echoes of stair halls and bathrooms. We feel the temperature change when we step into a shaded courtyard. This interactivity generates curiosity. We wonder because we have had an experience, and the space has become relevant to use because we are in it. These spaces are authentic—where something really happened—where we can allow ourselves to be transported in time.6

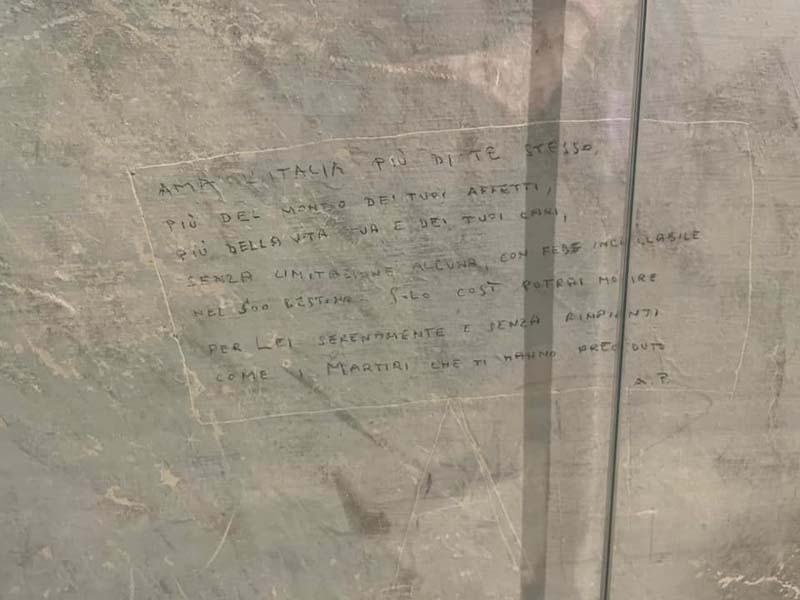

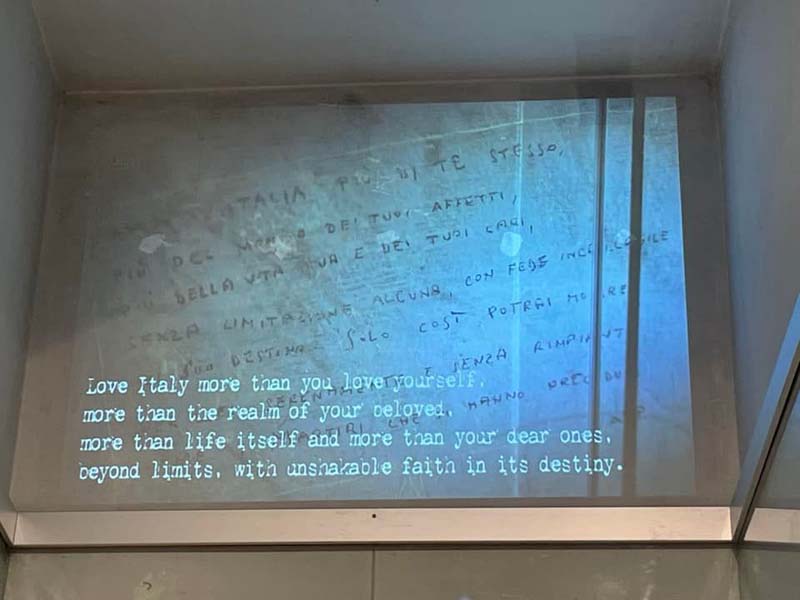

This authentic immersion was a key piece of the power I experienced in a small museum on Via Tasso in Rome—the Museum of the Liberation of Rome. In this nondescript apartment building there is a museum made up of two former apartments that were used by the SS as a prison during World War II. The museum clearly operates on a limited budget. Their displays are old-school and relatively simple, and yet being in the space where prisoners were actually kept (and killed) makes reading the smuggled notes from their families feel so much more moving. A highlight of the museum was a closet that was used by the SS as a solitary confinement cell. The walls of this space are covered in graffiti carved by prisoners—many of them sending a last message to a loved one, or making peace with their actions before their death. The closet included a projection of some of the graffiti being read out loud and then translated to English. It was incredibly moving. I sat on the floor of that closet for a long time.

My favorite heart-wrenching piece was “Love Italy more than you love yourself, more than the realm of your beloved, more than life itself and more than your dear ones, beyond limits with unshakable faith in its destiny.”

Figure 25: Graffiti on the cell walls at The Museum of the Liberation of Rome.

Figure 26: Graffiti projected as being read out loud in Italian and English.

Beyond the authentic immersion of being in the space where something actually happened, I want to add that interacting with the past is sometimes most compelling when the experience is unexpected. Yes, I was deeply connected to history at the Museum of the Liberation of Rome, but I chose to go there and I paid a fee to enter. Knowing that this is a powerful place doesn’t actually help reach everyday people, and so I want to add a few examples of effective forms of urban serendipity—places where people can just stumble across opportunities to interact with the past as they go about their lives.

The first of these are the stumbling stones used to mark the former homes of Jewish people murdered by the Nazis. I first saw these in Venice, but have now also seen them in Vienna, Prague, Budapest, and Berlin. These are small bronze squares fitted into the pavement replacing ordinary pavers. Each one bears one person’s name, birthdate, date taken by the Nazis, and, for most of them, date of death. They are placed in front of that person’s last known address. As people walk through cities they will “stumble” upon them and are free to interact with them in any way they like. I know, largely through conversations with European historian Emily Gioielli, that these stones are contested for several reasons. I admit that they are imperfect memorials, yet I want to talk about some of the reasons I think they work. Visitors (myself included) come upon stumbling stones by accident outside an ordinary apartment building. They are permanently embedded in the pavement and they will be there whether we notice them or not, but if we do notice them, they give a surprising jolt of “Something horribly tragic happened in this place. This ordinary place exactly where I am standing.” For me the next thought was, “If it could happen in this place, it could happen anywhere, like in my neighborhood or my city.” This cautionary impact is, to me, their greatest value. Yes, they pay homage to one person and commemorate an individual death. They become available to families to visit as a gravestone would for people properly buried. They bring echoes of the past into the present. To me, their greatest power is to remind us not to ever let the past they mark into our future.

Figure 27: Stumbling stones in Venice.

To close I will offer two more humble and human forms of interaction I saw in Budapest that I think might offer models for public historians and preservationists. The key to these monuments is that they involve ongoing human action and interaction.

The first is Budapest’s Memorial to the Victims of German Occupation. Here the government put up a monumental sculpture without public input. The monument seems to imply that big-bad Germany, symbolized by an eagle snatching the royal orb from the hands of innocent Hungary, was solely responsible for the murder of Hungarian Jews. The reality is that Hungary was complicit in the murder of the nation’s Jews. There was so much controversy over this monument that it was actually erected in the middle of the night. When Budapest’s Jewish community saw the lie this new monument implied, they built a moving counter-memorial across the street from the official one. This makeshift monument, now weathered and decaying in a very evocative way, includes shoes and suitcases of murdered Jews dug out of attics and closets and offered up in protest. It includes photocopies of photos and documents, and typed stories of the harm Hungary did to its own Jewish population. This second monument has a powerful loud voice and tells visitors that something important is going on. It invites interaction as visitors leave stones as one would at a Jewish grave.7

Figure 28: Memorial to the Victims of German Occupation, Szabadsàgtèr, Budapest showing counter-memorial across the street

Figure 29: Detail of the counter-memorial.

Finally, there is a more formal form of ongoing interaction with the past I found in Budapest. This is the hanging of wreaths. The city is covered in plaques on façades commemorating this or that famous person or this or that historical event. These are exactly the kinds of plaques that most people completely ignore in their real lives. What is different in Prague is that under most of these plagues, there is a small hook where people can hang wreaths and other memorials. When I asked a guide about who puts the wreaths on the hooks, he said it was usually the neighborhood councils, but that if an individual person put up a wreath or a ribbon that would be fine, too. What this regular active commemoration did was to transform these wall plagues from a static background to urban life into an active changing place. A new green wreath or colorful bows would appear at some important moment in the year, then wilt, weather, and fade until they were taken away to be renewed again next year.

Figure 30: Plaque with wreaths in Budapest. Though this one clearly features an early figure in Budapest’s history, plaques with a hook below are all over the city and commemorate figures up to the very recent past.

When I wrote my first blog post I naively thought I might find one brilliant model that would help everyday people read and appreciate the built environment. What I have found instead is that that work will require new creativity and innovation. I think I have identified some of the components that make might generate curiosity in urban environments, but I definitely haven’t discovered a magic formula. I am hopeful that reading this blog will stimulate your creative thoughts about reading buildings and creating engaging urban experiences. Maybe together we can unlock the secret. I would love to know what strategies you have seen and what you consider the best tools for urban engagement.

1 Zuzana Ragulová . “Czech Art Nouveau Architecture in the Cities of Prague, Brno, and Hradec Králové.” Delivered at the coup Defouet II International Art Nouveau conference, 2015, 2. http://coupdefouet.es/admin_ponencies/functions/upload/uploads/Ragulova_Zuzana_Paper.pdf

2 Jindřich Vibyral. “Friedrich Ohmann and Prague Architecture Around 1900,” Peter Burman (Ed.) Architecture 1900 (Shaftsebury, Dorset: Donhead, 1998),173.

3 Michael Kohout, Vladamir Šlapeta, & Stephan Templ (eds). Prague: 20th Century Architecture (Vienna: Springer-Verlag, 1999), 22; Zdenek Lukes. Prague Modern: Architectural City Guide 1850–2000 (Prague: Paeska Publishers, 2018).

4 Zdeněk Lukeš. Prague Modern: Architectural City Guide 1850–2000 (Prague: Paeska Publishers, 2018), 232–233.

5 Ibid., 32–33.

6 Lots of people have written about authenticity. I like Sharon Zukin’s discussion of it in Naked City.

7 If you would like more detail about this controversy, you can check out this blog post: https://historycampus.org/2015/erect-a-memorial-erase-the-past-the-memorial-to-the-victims-of-the-german-occupation-in-budapest-and-the-controversy-around-it/

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top