-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

The Re-Making of Hiroshima as Peace Memorial City after the Bomb

Sundus Al-Bayati is the 2019 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

One of the first things I read at the beginning of this fellowship journey was John Hersey’s Hiroshima. A small pocket-sized book, it was hard to get through its page after page of graphic content of the first few moments and days after the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima by the US military. In the book, six survivors of the bomb at various distances from the hypocenter recount their stories before, during, and after the explosion. It’s hard to unlearn what could happen to the human body when exposed to the heatwaves of a nuclear blast. These stories came back to me when I arrived to Hiroshima, the city-turned-memorial to the event of August 6, 1945. After the war, Hiroshima was a nuclear wasteland: more than a third of its population, around 140,000 people, had perished in the explosion and the effects of radiation several days and months after the bomb.1 With more than 70% of its buildings destroyed and its industrial sector disbanded, the city had very little of a path forward.

Not long after the war ended, Hiroshima quickly went from a city ravaged by the atomic bomb to the poster image of international peace. The narrative that immediately began to dominate the post-bomb climate in Japan promoted images of rebirth and new beginnings: the dawn of a new Hiroshima that was a symbol of peace and hope rather than the reality evident in its radioactive landscape, that the city was the tragic recipient of the first nuclear bomb in history.

The acceptance and advancement of this narrative by Japan and Hiroshima’s local leaders was essential, however enforced, for the city’s survival and growth under the American occupation that lasted until 1952. The occupation’s mission to “democratize” Japan meant controlling the country politically and economically as a whole, and in the case of Hiroshima, a direct censorship of journalistic investigation and scientific and medical research into bomb-related damage and radiation effects on victims.2 Instead, the United States promoted imperialist propaganda that regarded the atomic bomb as an American scientific achievement that was crucial to ending World War II and thus bringing peace to the world, justifying the human cost of the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Japan’s defeat in the war was announced on the radio when the emperor of Japan spoke to the Japanese people directly for the first time and presented Japan’s surrender as necessary and even heroic to prevent more senseless deaths of Japanese citizens. Japan’s only path towards reinventing its economy and rebuilding after the war was through accepting and promoting reconciliation of US-Japan relations.3 In Hiroshima, the local government, desperate to rebuild, began to publicly embrace a similar view of the bomb as the colonizer’s, that Hiroshima’s suffering and sacrifice was a prerequisite for peace.4 This is not to say that there wasn’t a sincere desire by Hiroshima’s citizens to envision a new city that symbolized peace and hope for a better future after the most devastating experience in their history but being under the US occupation, Japan had little agency in crafting its own story. The interpretation of the atomic bomb as an impetus of peace was beneficial to the US interests in Japan as an ally in the Cold War. For Hiroshima, historically a major military center, rebuilding with the message of peace also provided a possible path to economic recovery during the challenging post-war years.

With many Japanese cities devastated by the end of the war and limited government funding available for reconstructing industrial infrastructures, Hiroshima pursued a special consideration for assistance from the national government for its unique condition as a victim of a nuclear bomb.5 While reconstruction efforts began shortly after the war, in 1946, the vision of rebuilding Hiroshima as a memorial city became a viable opportunity with the enactment of Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law of 1949. The law directed special financial assistance and national land to aid in Hiroshima’s reconstruction, even when other major Japanese cities, like Tokyo, had suffered greater physical damage. A group of architects led by Kenzo Tange won the competition to plan and design Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, encompassing the area that fell under the bomb’s hypocenter. The park occupies a large area of the city, roughly 122,000 square meters, in what used to be a bustling and central downtown district prior to its annihilation by the atomic bomb. It is not so common that a city decides to transform its most central and valuable real estate district into an open memorial park in the reconstruction years, but rebuilding Hiroshima carried a symbolic importance greater than all the other badly damaged Japanese cities, including Tokyo. Hiroshima’s destruction was unique. As early as 1946, tourists, encouraged by tourism pamphlets produced by the US army, began to flock to Hiroshima to see the ruined site of the “Atomic City.” This proved that Hiroshima’s future could be found in the preservation of its history as the site of the first atomic bomb.6

I arrived at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park from the east side after crossing the Motoyasubashi bridge, which miraculously survived the blast, despite being only 100 meters away from the hypocenter. It was a rainy day, which made the memorial park feel even more somber. My first stop was the Children's Peace Monument that commemorates the children of Hiroshima who died as the result of the bomb. The monument is dedicated to Sadako Sasaki, who died at the age of 12 after struggling for 10 years from exposure to radiation during the blast when she was two. The monument consists of a statue of Sadako holding a crane over her head and surrounded by glass cases full of colorful paper cranes. Origami paper cranes are a symbol of healing and long life in Japanese culture, and they became associated with Sadako’s story because she folded 1,000 cranes during her final months in the hospital.

Figure 1. Children’s Peace Monument

In the distance, I could see the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum’s main building floating over the park, sitting at the end of the axis that pulls visitors through the Flame of Peace and the Cenotaph for the A-Bomb Victims first before arriving at the museum, where they will come in close contact with the grim details of August 6, 1945. I entered the main building, the part of the museum that is dedicated to the damage of the bomb to Hiroshima and the effects of the blast and radiation on victims. Exhibits of dark gray walls take visitors through room after room in semi-darkness, creating an oppressive atmosphere where visitors have no choice but to face the difficult artifacts presented under the spotlights. The contents of this section included personal articles of clothing and objects that were on the victims when they vanished in the blast and large graphic photographs of irradiated victims with harrowing injuries and deformities. Passing by these photographs, I began to quicken my pace to reach the end of the exhibit course as I began to feel heavy and confined. Conveniently, this dark section ends with releasing visitors into the airy and light-filled volume of the gallery hall overlooking the memorial park where visitors can stop to rest, take in the views of the park, and sit with their discomfort in this dark city.

Figures 2–3. Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park

Figures 4–5. Cenotaph for the A-Bomb Victims

Figures 6–14. Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

Figure 15. Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum’s main building gallery looking out into the memorial park

Figure 16. View from Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum towards the memorial park and A-Bomb Dome

Leaving the museum, I headed towards the most iconic building in Hiroshima and where most tourists can be found, the Atomic Bomb Dome (Genbaku Dome). Standing on the east side of the Motoyasu River is a skeletal structure of what remained of the Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, which was right at the center of the blast and somehow remained standing. In its glory days, the building served as an exhibition space that was used for displaying the prefectural industrial products of Hiroshima. Genbaku Dome, which later became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996, is perhaps the most visited site in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. But its preservation was controversial as most Hiroshima residents wanted the building removed because it was a reminder of a very dark and painful day. Nonetheless, junior and high school students persisted to advocate for the building’s preservation as an important part of the city’s history, and the city council of Hiroshima decided to preserve the building in 1966.7

Figures 17–25. A Bomb Dome, Hiroshima

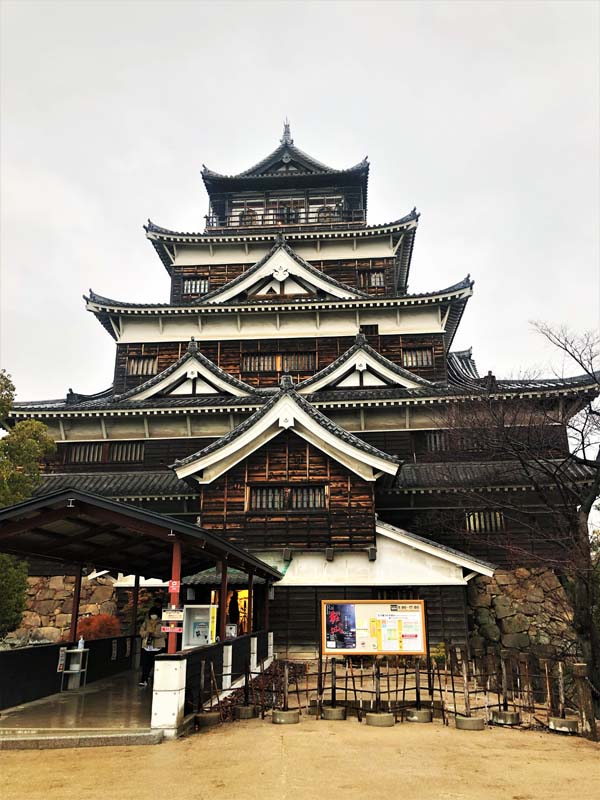

Figures 26–27. Hiroshima Castle, a reconstruction from 1958 of the 1590s original building that was destroyed during the atomic bombing of Hiroshima

Figures 28–31. Views from Hiroshima Castle

Being in Hiroshima, immersed in the memories of the atomic bombing, I reflected back on Tokyo’s lack of a trace or a memorial to the firebombing of 1945. One of the first destinations I outlined for Tokyo was the Center of Tokyo Raids and War Damage. I went there during the first week of my fellowship, eager to start my research in what I thought was a major museum on the history of the US’ firebombing of Tokyo. Surely such a historic and painful episode in the history of Japan that claimed 100,000 lives in a single night would be documented and exhibited extensively, I thought. I was confused when I arrived at what resembled a three-story apartment building from the outside, set in the residential and quiet neighborhood of Koto City. The entrance was marked with a small eyebrow awning and the location on my Google maps all pointed to this being the center I was looking for. I entered. The place was empty. I peeked around and found someone working in a small administrative office. I asked him if I was in the right place and he confirmed but let me know that the center was closed that day. I told him their website said otherwise. He tried to explain something in broken English, then gave up and came over to cut me a ticket and told me that I could enter even though it was closed. So I had the whole place to myself for an hour and a half. The kind man pointed me to the first room of the exhibit and disappeared. Again, I was surprised. This was just a small room with some printed materials on the walls, not the museum experience I was imagining for such a historic event. The large prints on the wall started with a timeline leading up to the night of March 10, 1945, when the US dropped 1,665 tons of incendiary bombs on Tokyo. There were maps outlining damage to Tokyo’s neighborhoods, objects from victims, photographs and original art of the night of the raid and a model of the bombs carried by the B-29 bombers. Warning signs on the walls asked visitors not to take photos of the paintings and personal artifacts exhibited in the rooms.

The last room briefly discusses the efforts that led to the establishment of the center, which started documenting and collecting artifacts about Tokyo’s air raid damage since 1970. The center was built in 2002 from exclusively private donations when government plans to build a memorial hall for the firebombing of Tokyo fell through in 1999. The center doesn’t elaborate more on the Japanese state’s neglect to memorialize the events of March 10, 1945, but there are few theories as to why Tokyo’s reconstruction steered clear from creating spaces of remembrance. For one, Japan’s need to sustain its relationship with its new ally, the United States, necessitated an avoidance to memorialize the atrocities committed by the US military in Japan. Second, a memorial site to the firebombing of Tokyo would call into question Japan’s own legacy of firebombing Chinese cities.8

Examining Tokyo and Hiroshima side by side, two Japanese cities that have experienced a similar degree of destruction and trauma but with one city determined to remember and the other to forget, shows the power of reconstruction as a political tool to reach certain ideological and economic outcomes, often times divorced from the real needs of a place after war. The narrative of peace allowed Hiroshima to gain support for its reconstruction from both the Japanese national government and the US. For Japan, Hiroshima’s new identity as a Peace City would rebrand Japan’s image on the world stage after the war from the atrocities it had itself committed in China and Korea. For the US, shifting the conversation of the bomb from a war crime to that of peace was favorable to its own narrative of the bomb as a saver of lives.

References

1 Koichiro Matsuo, “Urban Reconstruction and Symbol Systems: How Hiroshima Became a Peace Memorial City.” The Teikyo University Economic Review, 49(2): 123–137, (2016).

2 John W. Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (New York: W.W. Norton & C./New Press, 2000).

3 Ibid.

4 Ran Zwigenberg, “The Atomic City: Military Tourism and Urban Identity in Postwar Hiroshima,” American Quarterly 68, no. 3 (2016): pp. 617–642, https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2016.0056.

5 Koichiro Matsuo, “Urban Reconstruction and Symbol Systems: How Hiroshima Became a Peace Memorial City.” The Teikyo University Economic Review, 49(2): 123–137, (2016).

6 Ran Zwigenberg, “The Atomic City: Military Tourism and Urban Identity in Postwar Hiroshima,” American Quarterly 68, no. 3 (2016): pp. 617–642, https://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2016.0056.

7 Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

8 Yoshikuni Igarashi, Bodies of Memory: Narratives of War in Postwar Japanese Culture, 1945–1970 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011).

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top