-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

SAH Dissertation Research Fellowship Report: “The Phantom of Empire: Qing Stagecraft of Art and Theater, 1700–1827”

Jan 12, 2024

by

Tong Su, 2023 SAH Dissertation Research Fellowship Recipient

My dissertation project, titled “The Phantom of Empire: Qing Stagecraft of Art and Theater, 1700–1827,” focuses on the temporary stage architecture of the Qing Empire. I collected data by visiting various sites in Beijing to unearth traces of these cultural relics. A particularly striking site was Taoran Pavilion Park in the city’s southern part.

The park is marked by a vertical layout, crowned by a natural earth hummock, about 10 meters high, on the northern bank of a landscape of lakes, reeds, and bushes. Historically, this site was the center of an imperial kiln during the Yuan and Ming dynasties.

However, in the Qing Kangxi era, its role as a kiln ceased, and it transformed into a favored spot for celebrating the Double Ninth Festival, offering panoramic views. In the early twentieth century, during the republican era, it became a practice

ground for trainees of the Fu Lian Cheng Peking Opera School, who would gather to sing and drink tea.

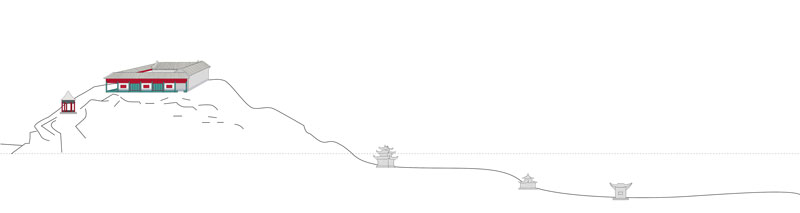

Diagram of Taoran Pavilion Park. Drawn by Tong Su.

Today, the earth hummock, standing as the park’s highest point, is encircled by pavilions laid out on a lower plane. These structures, replicating famous designs from other regions, were

erected in 1985 by the local government as part of an urban beautification initiative. Though these replicas are dimensionally accurate, they lack the historical and cultural resonance of the original structures. The lower area, bustling with visitors

and wrapped in humidity, presents an artful outdoor setting with these pavilion models, yet it lacks substantial cultural activity.

The terrace on the earth hummock includes a pavilioned corridor, a vibrant hub for singing gatherings. This

spot is frequented by local elders skilled in Pihuang opera for practice. During my initial visit, an elder singer unexpectedly invited me to perform an opera song, a customary welcome ritual for newcomers. A kind lady performed a piece from The Jewelry Purse 锁麟囊 and told me that this “long pavilion 长亭” is deemed ideal for group opera practices. I noticed that the pavilion’s acoustics favor lower male voices, complementing the deep tones typical of male laosheng老生 roles in opera.

Conversely, the acoustics are less advantageous for the higher-pitched female dan 旦 roles, which usually prefer more tranquil spaces. This acoustic feature might account for the pavilion’s popularity among male singers. The prime location

within the pavilion is at the corner where the two corridors converge, producing an echo effect, further enriched by breezes rustling through adjacent pine trees. This atmosphere is reminiscent of Chinese paintings that portray literati assemblies

in mountainous settings, accentuated by lyrical performances.

In my study of the interplay between pavilion architecture and Chinese opera, I reflected on the term “pavilion” as used in Qing dynasty texts. A Kangxi-era dictionary describes “ting (pavilion)” as a resting spot on a journey. Meanwhile, the Manchu translation, “ordo”—stemming from the Mongol term for a mobile tent or horde—suggests movement. These interpretations, while sharing the theme of a sojourn, diverge in their nature: “ting” impiles stillness, whereas “ordo” implies motion. This nuanced understanding likely influenced the Qing Manchu view of pavilions, leading to a multifaceted concept and possibly facilitating their use as temporary stages for itinerant performances.

These insights gained from my fieldwork have been enlightening. First, the park exhibits a distinct vertical spatial arrangement: its lower level bustles with tourism, while the upper level, serene and culturally enriched, hosts genuine cultural events, balancing between public entertainment and exclusive cultural niches. Second, I observed that specific Chinese architectural styles, like pavilions, inherently draw lyrical activities. The Manchu translation of “ting” and the etymology of “ordo” together suggest a fascinating historical evolution, in which the pavilion transformed from a simple temporary structure into a centerpiece for itinerant lyrical expressions.

My rough diagram of Taoran Pavilion Park illustrates these findings, contrasting the lively, replicated pavilions on the lower level with the tranquil, culturally significant upper level. Accompanying this is a soundtrack that captures the diverse

acoustic environment of the mountain pavilion, highlighting its strategic position and unique sound qualities that render it a sanctuary for opera enthusiasts.