-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

On Territory: Extractive Sovereignty and Australian Empire

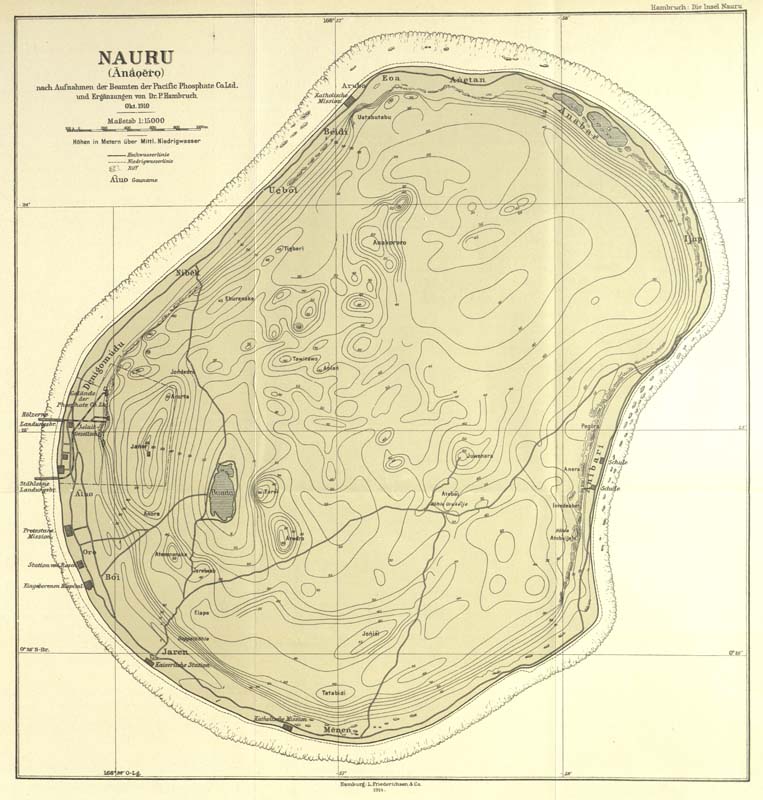

Nauru is a 21-square-kilometer island republic in Micronesia that frequently appears on lists of the world’s least visited countries (figure 1). I first lay eyes on it shortly before nightfall from the small old plane that has conveyed me there over 3,300 kilometers from Brisbane: an almost imperceptible terrestrial ripple on the otherwise glassy surface of the Pacific Ocean. The plane’s once white internal fit-out is yellowed with age and its fuselage lets out a reluctant croak as we bank towards the short landing strip. Plummeting towards the land, passengers shrieking at the rapid rate of descent, I make out the coral reefs fanning the perimeter of the island and the narrow strip of development—shops, houses and industrial facilities—encircling the dark mass of its interior (figure 2). After taxiing to the airport terminal in Yaren District—Nauru’s 1.5-square-kilometer capital—we disembark onto the hot tarmac. The air is heavy and still, carrying the sound of music and the clamor of traffic noise from the nearby Island Ring Road. The sun sets quickly at the equator and before long the low-hanging clouds have been consumed by the muggy night. I climb into an air-conditioned van and am shuttled to one of the three hotels on the island: a sprawling, faded complex that stares out at the oil-slick sea (figures 3 and 4).

Fig. 1. Satellite image of Nauru. The airstrip is visible in the south of the island, as is the coastal development running around its perimeter. The lighter vegetation in the center indicates former phosphate mining sites. The clearings are either active mining sites or the locations of the Regional Processing Centers—the Australian immigration detention facilities run as part of Operation Sovereign Borders. Image courtesy of the U.S. Department of Energy Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) user facility.

Fig. 2. View of houses along the Island Ring Road from the plane shortly before landing.

Fig. 3. The view from reception at Menen Hotel.

Fig. 4. One of the many stray dogs on Nauru next to Menen Hotel’s function center where, on my first night on the island, the President held a private party for his ministers until late at night.

Nauru is a raised coral atoll formed by the erosion of a large volcanic seamount over millions of years. As sea levels dropped, the coral reef became dolomitized by seawater and eroded in the tropical conditions, leaving large limestone pinnacles mounding to around fifty meters to form the central plateau of the island, known today as Topside (figure 5). These pinnacles, many of which still bear impressions of the coral once attached to them (figure 6), were filled in by humus and seabird excrement over millennia to create vast rock phosphate deposits up to several meters deep covered by dense jungle. Human settlement of Nauru is estimated to have occurred at least 3,000 years ago by Micronesians who established a political system on the island based on twelve tribes. A distinct language developed, aquaculture was practiced in the freshwater Buada lagoon, and coconut palms and pandanus trees were cultivated to sustain a fluctuating population of between 1000 and 3000 people (figure 7). The lack of a natural harbor and the extreme isolation of Nauru from other islands—the closest of which, Banaba (Ocean Island), is located some 300 kilometers away in the Gilbert Islands—delayed contact between Nauruans and the European whalers and traders operating in the region until the late nineteenth century. By 1887, the year in which Nauru was incorporated into the German Marshall Islands Protectorate, there were only ten white residents on the island, all of whom were trading in copra.1

Fig. 5. Limestone pinnacles are all that remain once the phosphate deposits have been exhausted. The denuded landscape stretches across the entire area of Topside, Nauru’s central plateau.

Fig. 6. Many pinnacles still bear the impressions of the coral reef that grew from them thousands of years ago.

Fig. 7. Buada Lagoon, a small freshwater catchment on Nauru’s central plateau, was once used for farming Milkfish. A subterranean freshwater pool on the coast served as the island’s water supply until it became saline as a result of phosphate mining. Drinking water is now produced by four desalination plants on the island.

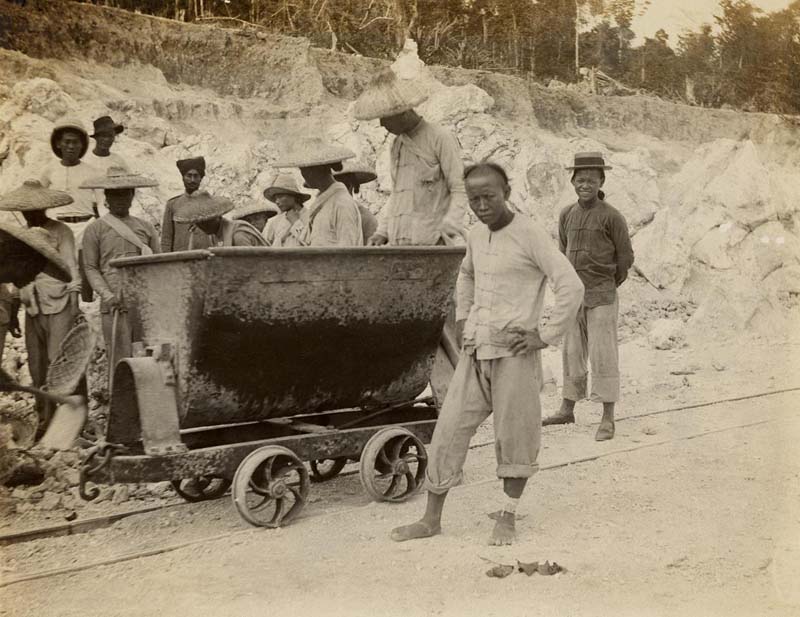

European interest in Nauru escalated dramatically with the discovery of its rock phosphate deposits in 1900 by Albert Ellis of the London-based Pacific Islands Company. As recounted in my second report, the Company presented a paradigmatic example of Greater British enterprise in the Western Pacific, combining capital and expertise drawn from throughout England, Australia, and New Zealand to realize the value of Pacific commodities within the markets of industrial capitalism. With Ellis’s discovery of phosphate on both Nauru and Banaba, the Pacific Island Company was quickly liquidated and reconstituted as the Pacific Phosphate Company (PPC) in 1902, attracting significant investment from William Lever—later the Lord Leverhulme of Unilever fame—and appeasing the German colonial authorities on Nauru by reserving a portion of the new company’s board for German representatives. Within a decade of establishing the PPC, close to 300,000 tons of phosphate were leaving Nauru and Banaba annually, extracted and processed by thousands of indentured laborers and bound for superphosphate manufacturers at ports in Australia and New Zealand (figure 8).2

Fig. 8. Indentured laborers from the Gilbert and Ellice Islands c.1910 working the phosphate deposits on Nauru. The phosphate can be seen between the limestone pinnacles. The former surface level of the island, prior to mining, can be seen in the background. Maslyn Williams Nauru Photographs, State Library of New South Wales, PXB 293, Image 59.

Fig. 9. The Nauru Phosphate Royalties Trust building in Arijejen. The Trust continues to pay royalties to the landholders on which phosphate mining takes place.

Following World War One, the phosphate deposits on Nauru and Banaba were set aside for the exclusive use of British polities under the auspices of the British Phosphate Commission (BPC), which from 1949 also acted as the managing agent for the phosphate works on Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean. In 1967, the newly independent Republic of Nauru purchased the BPC’s mining assets, which were resumed in 1970 under the Nauru Phosphate Corporation. The profits of the now sovereign phosphate industry were managed by the Nauru Phosphate Royalties Trust (figure 9), which gradually amassed an international real estate portfolio spanning Australia, the Philippines, Fiji, Guam, Samoa, the United States, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom, as well as investing in a failed 1993 West End musical production about Leonardo da Vinci’s love life. Financial mismanagement and largely exhausted phosphate reserves eventually ensnared the Nauruan government in unmanageable levels of debt, leading it to pursue diverse avenues of investment through quid pro quo deals with foreign governments: a fleet of ambulances in return for supporting Japan’s stance on whaling; millions of dollars of Russian economic support following Nauru’s backing of the breakaway Georgian territories of South Ossetia and Abkhazia; Taiwanese investment in energy projects and medical facilities after Nauru recognized its sovereignty at the UN. In 2001, Australia established offshore immigration detention facilities on Nauru, which remain in use under the demonstrably inhumane Operation Sovereign Borders, including the construction of a collection of now abandoned one-room dwellings for those asylum seekers who opted to resettle on the island (figure 10).3 Shortly before I arrived, the Australian government extended its offshore processing agreement with Nauru, allocating $485 million AUD for 2023 alone, representing an annual cost of $22 million per asylum seeker held in detention at that time.4

Fig. 10. The housing provided by the Australian government at Anabar in 2017 for asylum seekers electing to permanently settle on Nauru. The dwellings were entirely empty for the duration of my stay on the island.

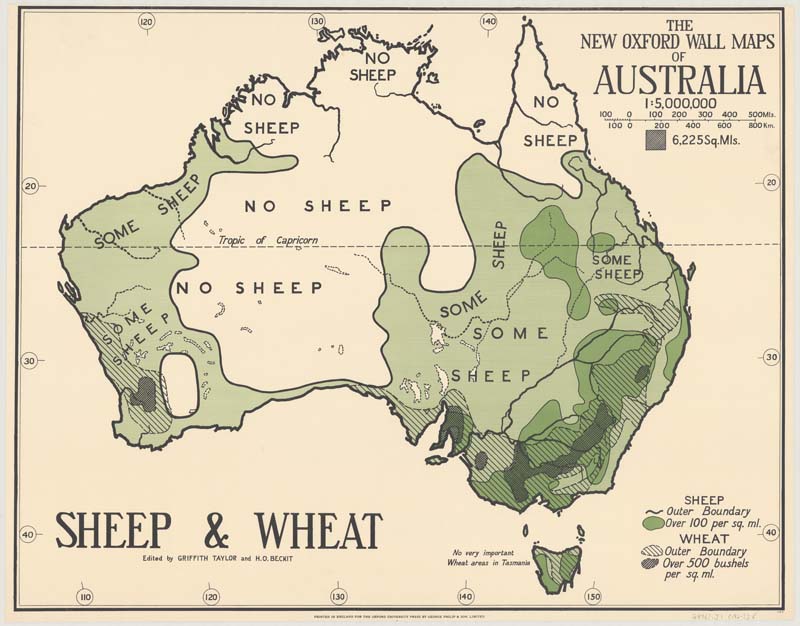

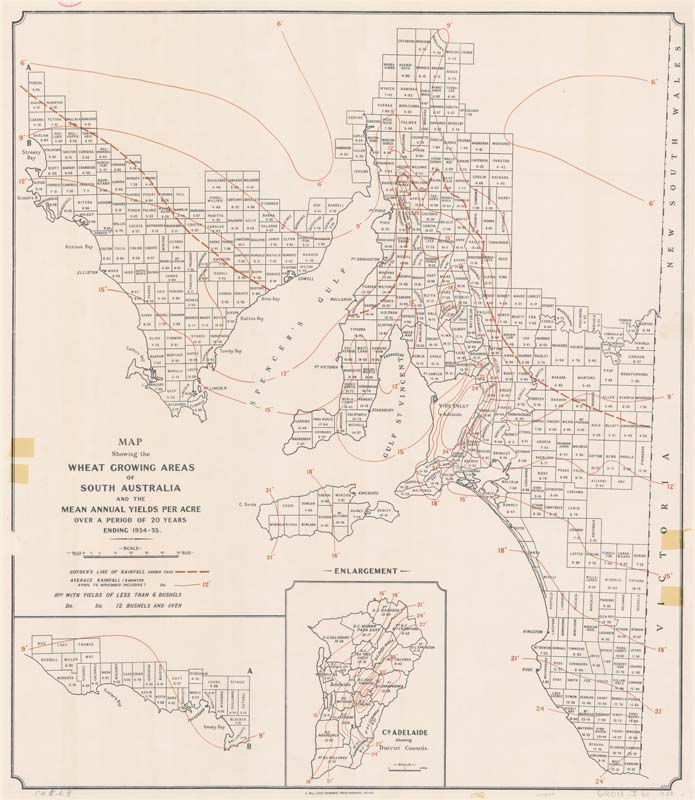

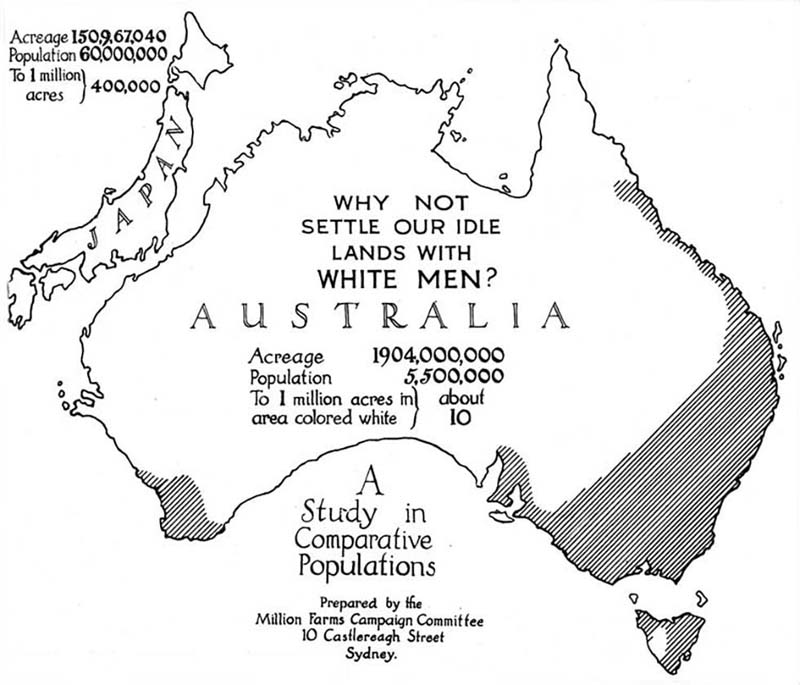

If Australians know anything about Nauru, they generally recite this potted history in reverse: from immigration detention to spurious international relations and bizarre investments to, eventually, phosphate, which is in turn usually misrepresented under the common Australian moniker for Nauru, “Bird Shit Island” (n.b., rock phosphate is not guano). However, Nauru’s controversies and idiosyncrasies belie a far more enduring and substantive relation between the two countries; one based on over a century of European resource imperialism linking the depletion of rock phosphate on Nauru with the expansion of Australia’s sprawling wheat industry; an industry that was itself fundamental to the extension of the settler-colonial project in Australia and the political economy of dispossessed Indigenous land upon which that project was premised (figures 11 and 12). Placing this relation at the center of Nauru’s tumultuous modern history both reveals continuities between the different forms of extraction first engendered by the phosphate industry and elaborated since—phosphate, finance, asylum—as well as the long history of Australian sub-imperialism in the Indo-Pacific, which continues to inform Australia’s expression of its so-called “external sovereignty” in the contemporary geopolitics of the region.

Fig. 11. The hatched areas on the map depict the distribution of Australia’s wheat districts in c.1920. Griffith Taylor and H. O. Beckit, The New Oxford Wall Maps of Australia: Sheep and Wheat (London: Oxford University Press, c.1920).

Fig. 12. South Australian Department of Agriculture, Map showing wheat growing areas of South Australia and mean annual yields per acre over 20-year period, 1935, National Library of Australia, 2828157.

In this reflection on my trips to Nauru and Christmas Island over the past few months, I return to a formulation discussed in my previous report and first proffered by the legal scholar Cait Storr in her recent study of the administrative history of Nauru: where legal status shifts, bureaucratic form accretes. According to Storr, the final shift in the legal status of Nauru from UN Trust Territory to sovereign state in the mid-1960s, “appears not as a break with but as a stage in the bureaucratisation of an imperial administrative form instantiated in the late nineteenth century” under colonial rule.5 The same can be said for the history of the administration of Christmas Island, from its original annexation by the British Crown in 1888 to its incorporation into the British Straits Settlements and the Crown Colony of Singapore, through to its management by the British Phosphate Commission from 1949 until its purchase by Australia in 1958. According to Storr’s formula, the evolution of both islands’ legal status was always subtended by the increasing bureaucratic rationalization of colonial jurisdiction, in the sense that “facilitating the outward flow of natural resources” from each territory remained “the raison d’etre of the state’s administrative form” as it shifted over time.6 And where the process of bureaucratization involves rules, jurisdictional areas, hierarchical structures, written documents and maps, these were ultimately all developed and deployed to enable the physical removal, processing and circulation of phosphate from the Indo-Pacific onto foreign soils. Storr’s formula thus inadvertently emphasizes the inherently material—technological, infrastructural, architectural—conditions of the extractive sovereignty she describes, even if these fail to enter her analysis per se.

My intention in this report is therefore to relate the linked administrative histories of Nauru and Christmas Island (and Banaba, which I was not able to visit in person) to the residual buildings, mining sites, facilities and industrial equipment I encountered during my travels.7 In light of the above discussion, I understand these different forms of spatial production both as relics of a colonial industrial enterprise that radically altered the ecological and societal conditions on the islands themselves, as well as vehicles in the stabilization of Australian sovereignty more broadly. As Storr explains, “‘Australia’ is necessarily understood as a sub-imperial as well as a colonial project. The Australian state is a colonial project built and maintained on the denial of Indigenous ownership of the continent,”8 but also on its “sub-imperialist posturing in the Pacific region” where the Australian colonies attained regional supremacy through the extractive activities of both public and private forms of authority.9 As the administrative histories of Nauru and Christmas Island elucidate, the territorial boundaries of ‘Australia’ have always exceeded the official limits of Australian sovereign territory in what amounted to a sub-imperial technological system linking remote resources with domestic production.10 The relics of this system remain strewn across both islands, readily accessible to the interested visitor.

Fig. 13. Views from my hire car #1: A house built into a limestone pinnacle.

Fig. 14. Views from my hire car #2: An abandoned four-story mansion in Ewa stands as a monument to Nauru’s former wealth during the 1990s.

I quickly lost track of how many times I circumnavigated the Republic of Nauru on the Island Ring Road in my hire car (figures 13 and 14). The trip takes approximately twenty minutes depending on the number of police checkpoints in operation, or whether the President is currently enroute somewhere in his black Lexus limousine. If he is, all cars are required to pull over immediately until he and his entourage have sped past. These were always good opportunities to tune into the island’s radio station, which in addition to broadcasting Australian news bulletins on the hour also played a variety of obscure disco songs on repeat—most notably “Oriental Boy” by The Flirts—along with a mix of more recent hits from across the Pacific. Tongaruan’s “I’ll be Drinking when I’m Hurtin’” was especially popular and remains on high rotation in my household at the time of writing. Other things I did not know about Nauru before traveling there: small quantities of phosphate are still mined and exported from the island, primarily to Australia and South East Asia; an imported Australian lettuce costs $18 AUD in either of the two supermarkets on the island; the country uses Australian currency dispensed by Australian banks; its schools use an adapted version of the official curriculum of the state of Queensland; its legal system is modelled on Australia’s; and, when Nauru brought the case to the International Court of Justice in 1989 that the Australian government had breached its fiduciary duty to promote the economic and social wellbeing of the Nauruan people by failing to remediate the phosphate mines worked almost to exhaustion during the period in which the island was a UN Trust Territory, the case was settled out of court four years later with Australia insisting that it would only pay penalties in the form of increased aid to avoid the public perception that it was criminally liable.11 Australian Aid logos are still littered throughout Nauru, affixed to shipping containers, generators, and buildings. The fact that the lucrative immigration detention facilities on Nauru are physically located in exhausted phosphate mining pits—the hottest, most exposed, windless sites on the island—puts a dark spin on the pervasive ways in which “remediation” and “aid” continue to inform Nauruan and Australian relations thirty years after the lawsuit was settled (see figure 1).

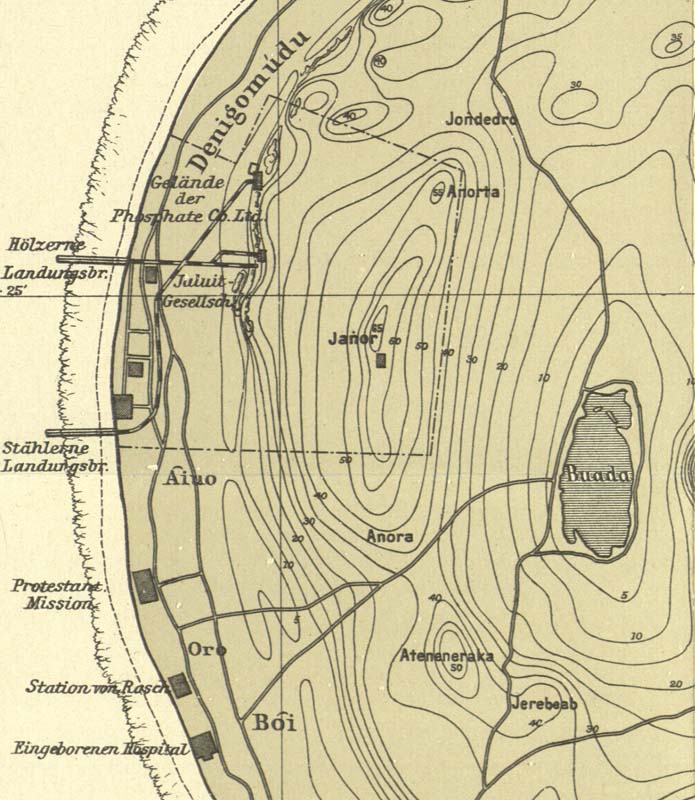

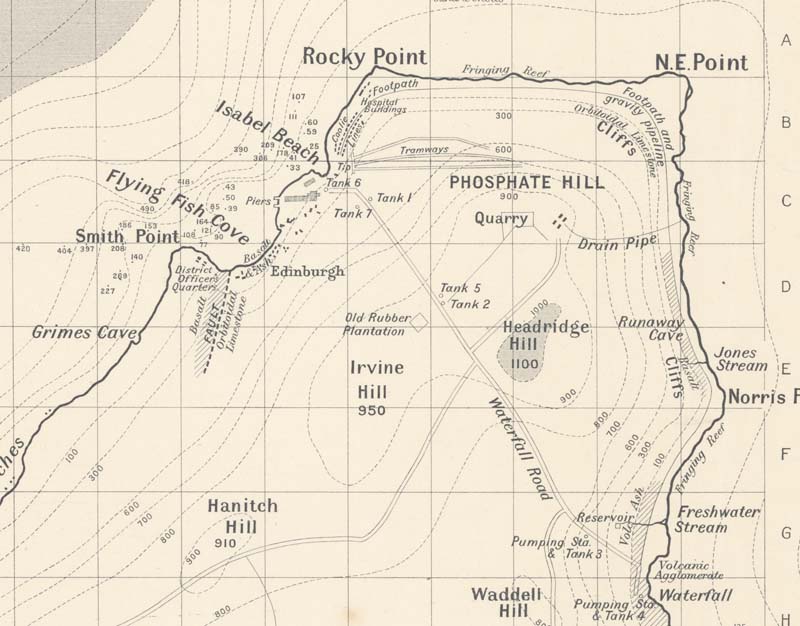

Fig. 15. Paul Hambruch’s map of Nauru during the early period of the Pacific Phosphate Company’s operations on the island, showing the Company’s facilities directly adjacent to those of the Jaluit Gesellschaft. The map was completed in 1914 based on observations made in October 1910. Paul Hambruch, Nauru nach Aufnahmen der Beamten der Pacific Phosphate Co. Ltd. und Ergänzungen von Dr. P. Hambruch, Okt. 1910 (Hamburg: L. Friederichsen & Co., 1914).

Fig. 16. Detail of Hambruch’s map of Nauru depicting timber (Hölzerne Landungsbr.) and steel jetties (Stählerne Landungsbr.) within the PPC’s original mining lease.

Fig. 17. One of two pivoting steel cantilevers currently used by Republic of Nauru Phosphate Corporation to load ships in the deeper water off the coral reef.

Fig. 18. Conveyors transport the crushed and dried phosphate to the cantilevers for loading.

Fig. 19. The steel cantilevers and conveyor system used on Nauru in c.1932, during the period of the British Phosphate Commission. Maslyn Williams Nauru Photographs, State Library of New South Wales, PXB 293, Image 116.

Fig. 20. The BPC’s steel cantilevers sit collapsed onto the coral reef, surprisingly intact given the corrosive environment and heavy seas they face.

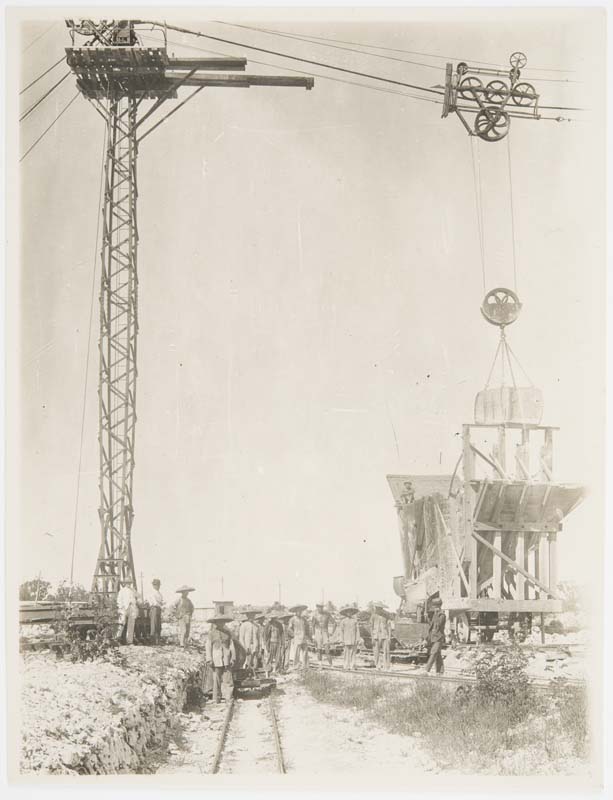

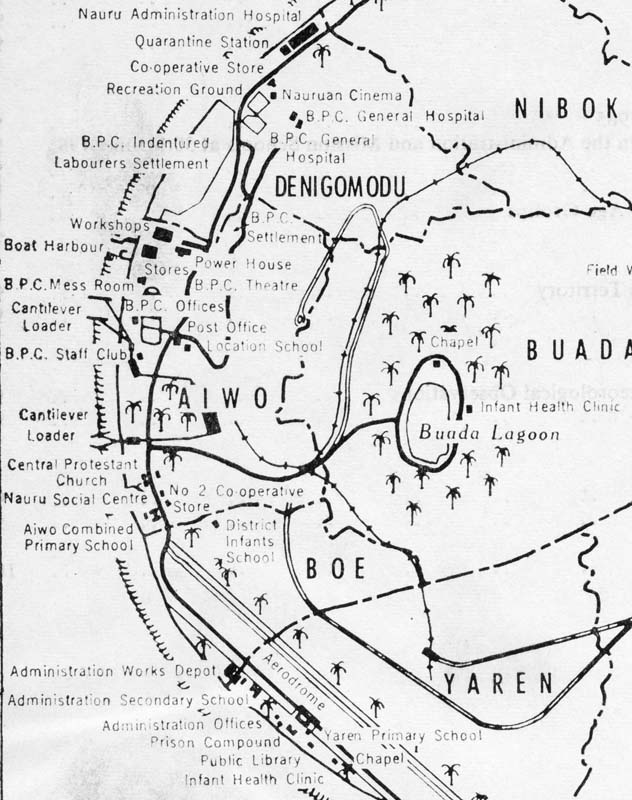

Eventually, my daily trips around Nauru started to yield results. An important document in this regard was Paul Hambruch’s 1910 map of the island, first drawn three years after the Pacific Phosphate Company had exported its initial shipments of mined rock (figure 15). The map shows two large jetties in the Aiwo district—one timber, one steel—protruding beyond the fringe reefs (figure 16). Driving to the site depicted on the map, I find the most recent iterations of the former jetties: large rotating steel cantilever structures connected to the phosphate crushing and drying facilities by a mechanical conveyor belt (figures 17 and 18). Further along the coast, two previous cantilevers, built in the early 1930s during the period of the British Phosphate Commission and destroyed by a German raider in World War Two, remain in place, collapsed face-first into the ocean (figures 19 and 20). With each increase in the length and speed of the loading facilities on Nauru and Banaba, annual exports of phosphate increased in turn, reaching a pre-1930s peak of more than 560,000 tons.12 To prevent the Company’s ever-larger steamers from being washed against the reef while under loading, Nauru also received the deepest moorings in the world, laid in 1200 feet of water (figure 21).

Fig. 21. Nauru’s moorings were the deepest in the world, tethered to the seabed by lengths of extremely thick chain, much of which now lies strewn along the coral beaches on the island. Shown here is Nauru Chief under loading in c.1932. Maslyn Williams Nauru Photographs, State Library of New South Wales, PXB 293, Image 114.

Fig. 22. A former tramway cut through coral pinnacles at the site of the PPC’s earliest mining activities on Nauru.

Fig. 23. The locomotives used to shunt phosphate carts from the mining sites to the loading facilities on Nauru were imported from Britain and Germany. Shown here is a steam locomotive in c.1915. The island’s aerial cableway can be seen in the background of the image. Maslyn Williams Nauru Photographs, State Library of New South Wales, PXB 293, Image 69.

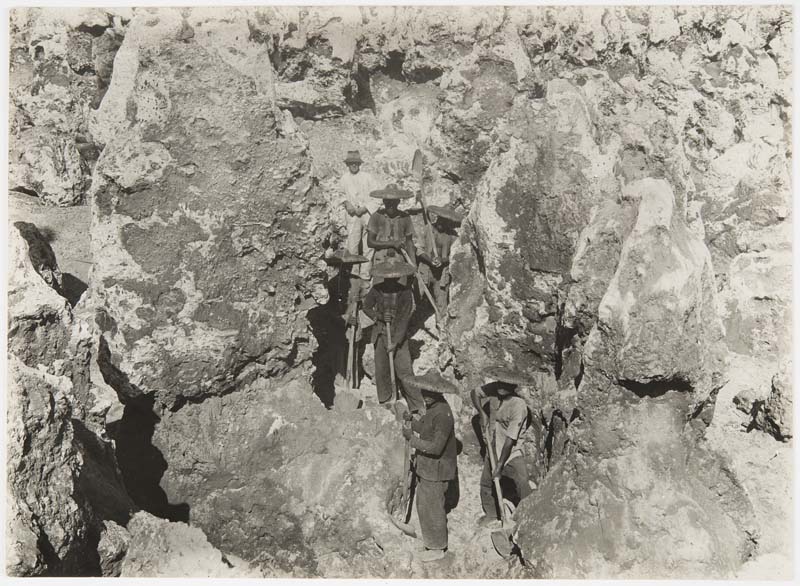

Fig. 24. Indentured Chinese laborers and a white overseer scraping phosphate from the limestone pinnacles at Topside in c.1915. Maslyn Williams Nauru Photographs, State Library of New South Wales, PXB 293, Image 60.

Fig. 25. Parts of the twentieth-century industrial equipment used to process phosphate remain dispersed around Nauru today. Seen here are likely the elements of a rotatory drying system, used to prepare the crushed phosphate prior to shipping according to international industry standards regarding moisture content.

Fig. 26. More parts—ducts, hoppers, trays and roof sheeting—in front of a disused phosphate conveyor belt overgrown by the resurgent tropical scrub.

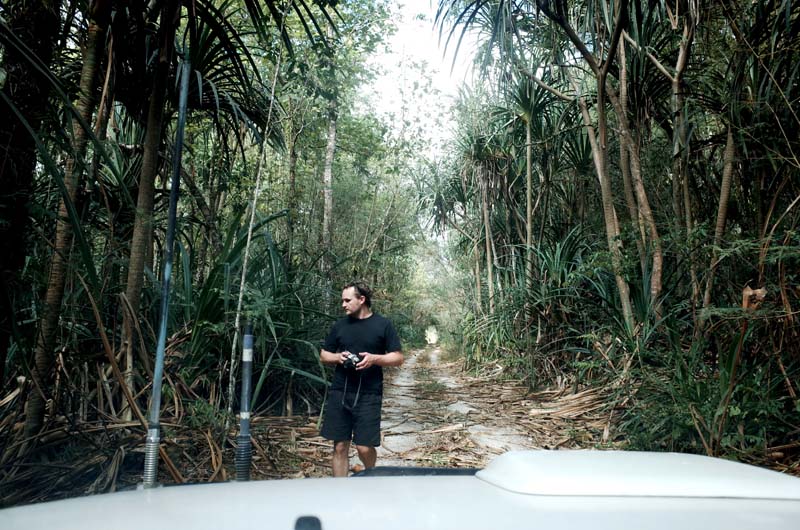

A dashed line on Hambruch’s map delineates the boundary of the earliest areas worked by the PPC, extending eastward from the Island Ring Road up the steep incline onto the raised plateau overlooking the loading facilities below (see figure 16). I navigate to the outer edges of the line in my hire car before stepping off the gravel road into the jungle where I find a maze of overgrown paths wending their way around countless limestone pinnacles (figure 22). I soon realize the paths I am following were once the tramways along which phosphate carts were shunted by small steam locomotives, filled by laborers who had pried the rock from the razor-sharp pinnacles by hand (figures 23 and 24). Dispersed all around me is the disarticulated detritus of a century-old mining operation: rusting tracks, cogs, ducts, and implements too disassembled to properly identify (figures 25 and 26). I push further east onto Topside, following a much larger railway embankment on either side of which the landscape has been comprehensively stripped back by mining—the pinnacles starting to disappear under ferns, creepers, and large figs (figure 27). I come across a brick coal store and kiln for fueling the early locomotives and find a small collection of cast-iron bowls, kettles, and ceramic Japanese dishes likely used by laborers on their lunch breaks to save the long trip down to the mess halls in the company settlement on the coast (figure 28). Large steel structures line the embankment (figure 29), possibly remnants of the aerial cableway that once conveyed mined rock from Topside to the processing facilities further downhill (figure 30)—a system designed by the Australian engineering firm J. M. and H. E. Coane, who acted as consultants for the PPC before World War One.

Fig. 27. Limestone pinnacles and the remnants of the aerial cableway connecting Topside to the processing facilities near the port.

Fig. 28. Bowls, dishes, and kettles found near the coal store and kiln at Topside.

Fig. 29. One of the steel structures lining the main embankment at Topside, likely the base for the aerial cableway designed by the engineers J. M. and H. E. Coane of Melbourne.

Fig. 30. The aerial cableway on Nauru in c.1915. Maslyn Williams Nauru Photographs, State Library of New South Wales, PXB 293, Image 65.

Fig. 31. A c.1930s former BPC officer’s residence in the residential quarter on the cliffs of Arijejen, once overlooking the phosphate processing facilities on the coast below.

Fig. 32. The house is being slowly consumed by a large Banyan fig, its roots penetrating the asbestos roof and timber floor.

Fig. 33. A different, c.1950s BPC officer’s residence in the residential quarter disappearing under a prolific vine.

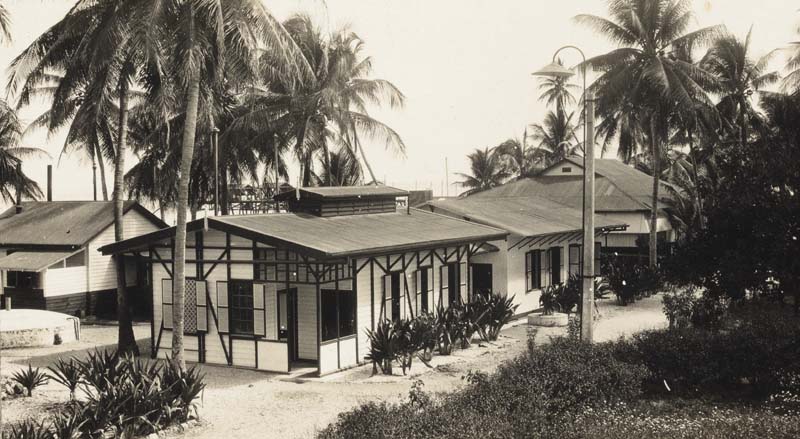

The redefinition of Nauru after World War One from Germany colony to UN Trust Territory under the League of Nations’ mandate system involved a joint payment of £3,500,000 to the PPC from the governments of the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand for the Company’s existing rights, titles, and industrial plants on Nauru and Banaba. Henceforth, the operations on both islands were managed by the British Phosphate Commission. The BPC’s tripartite model of governance, defined in the 1919 Nauru Island Agreement, assigned forty-two percent each of the costs and phosphate accrued by the BPC to the United Kingdom and Australia and sixteen percent to New Zealand. The remit of the Commission was to supply cost-price phosphate for chemical fertilizer manufacturers in all three member states, however in its first two years of operation alone, seventy-two percent of all shipments arrived in Australia; only five percent in the UK and New Zealand respectively; while eighteen percent was sold to other countries at market price to defray the BPC’s running costs. The administrative practices of the Commission maintained continuity with those of the PPC, employing the Company’s former executives—including Albert Ellis—as commissioners under the new arrangements. A large residential complex was developed on the slope between the port facilities and the mining sites on Nauru to house the families of the BPC’s white managers, engineers, geologists and doctors, now in a state of disrepair through gradual reabsorption into the dense jungle (figures 31, 32 and 33).

Fig. 34. The view from the BPC officers’ residential quarter overlooking the rows of housing at Location, primarily for Chinese laborers.

Fig. 35. The 1940s-era workers’ housing at Location was originally single-story but was extended by the BPC around 1960 to double its capacity.

Fig. 36. BPC housing for single white men near Location and the BPC’s main office on the island.

Fig. 37. The British Phosphate Commission’s office building on Nauru, built in the 1930s.

Fig. 38. The Pacific Phosphate Company Island Manager’s dwelling—Stanmore House—in c. 1919, initially used by the BPC and replaced in the 1930s with the office building depicted in figure 37. Maslyn Williams Nauru Photographs, State Library of New South Wales, PXB 293, Image 46.

Fig. 39. The BPC Mess Room, 1924, located in the main company settlement at Aiwo. T. H. Cude Nauru Island Photographs, 1920–1953, PXE 650 (vol. 2), Image 7.

Fig. 40. Location plan of buildings in the BPC’s company settlement at Aiwo, c.1965. T. H. Cude Nauru Island Photographs, 1905–1966, PXE 650 (vol. 1), Image 2.

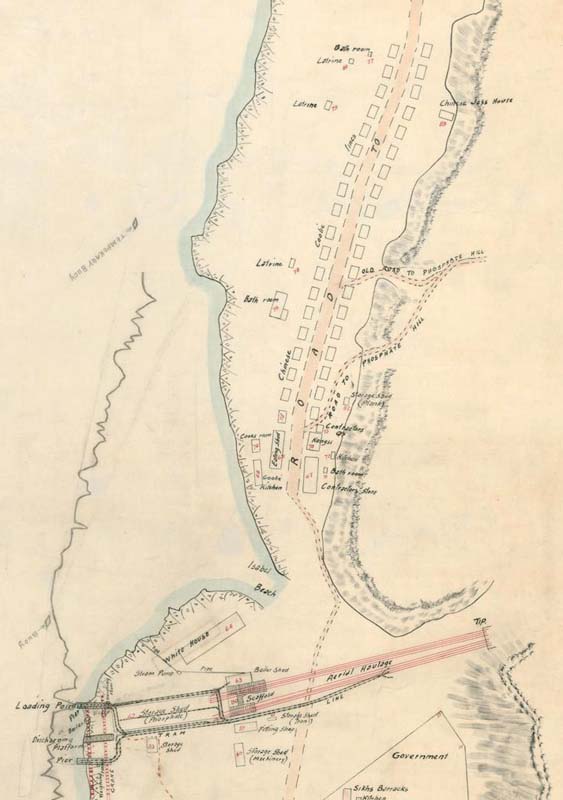

Continuity in administration between the Pacific Phosphate Company and the BPC also ensured the continuity of the foundational structures upon which phosphate mining on Nauru had been premised since the turn of the twentieth century. The use of indentured labor was significantly upscaled during the BPC period as evident in the rows of two-story walk-up flats located directly next to the boat harbor—a site still known today as Location—where primarily Chinese laborers and their families were housed (figures 34 and 35). Small standalone cottages adjoin the Location precinct (figure 36), built for single white men employed at the nearby mechanical workshop, phosphate loading facilities or in the BPC’s main administrative building, which has been repurposed as a site office for the ongoing redevelopment of Nauru’s port (figures 37 and 38). White-only recreational and utility buildings (figure 39)—a theatre, staff club, mess hall, stores, etc.—were dotted around the main office building, establishing a racially segregated modern enclave for the white governing minority on the island whose elevated form of living and assertive managerialism signaled to the outside world—including its strong critics in the League of Nations—that the BPC was fulfilling its obligations as an enlightened administrator of Nauru (figure 40). The architecture on the island remained an important tool in stabilizing and maintaining the racial hierarchies inherent in the colonial phosphate industry. Investment in the expansion and modernization of the islands’ mining facilities continued to be prioritized over the wellbeing of the non-white workforce, deemed essential but ultimately inexhaustibly replaceable within the system of indenture.

Fig. 41. View overlooking Flying Fish Cove, phosphate loading facilities and the Malay Kampong Group—formerly Edinburgh Settlement—on Christmas Island.

Fig. 42. Jagged limestone cliffs and thick jungle along the south coast of Christmas Island.

Fig. 43. A Brown Booby (Sula leucogaster), co-conspirator in the accumulation of Christmas Island’s phosphate deposits. Red crabs cling to the limestone cliffs in the background.

Fig. 44. Christmas Island Phosphates is only permitted to work existing mining sites on the island and cannot open new ones. Nevertheless, the sites are dotted throughout the Christmas Island National Park, much of which is coated in a pervasive layer of phosphate dust that washes into the water during the wet season causing degradation of the coral reef.

The same organizational logic and spatial relationships established within the phosphate industry on Nauru and Banaba remain evident 7,000 kilometers away on Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean (figure 41). Like its Pacific peers, Christmas Island is the geological result of an underwater volcano rising 5000 meters from the seabed and building coral reefs now interred as a limestone cap over the island’s basalt substructure (figure 42). Decomposing organic matter and the excrement of the thousands of birds that roost on the island each year accumulated on top of this limestone cap over millennia (figure 43), forming rich phosphate deposits that continue to be worked today by the Malaysian firm Christmas Island Phosphates (figure 44). Large road trains—trucks pulling more than two trailers—barrel along the wide roads cut through the Christmas Island National Park on the island’s central plateau, dodging the famous red crab on its annual migration from land to sea, before dumping the mined rock at a processing plant connected to the port by a dramatic elevated conveyor system (figures 45–53).

Fig. 45. Road trains barrel through the Christmas Island National Park. The metal guard running along the side of the road is designed to prevent the red crab from crossing. Instead, heavily engineered under- and overpasses have been constructed along the main roadways to assist the crabs in safely conducting their annual migration to the sea.

Fig. 46. The phosphate conveyor at Drumsite, overlooking Flying Fish Cove below.

Fig. 47. The phosphate tip at Drumsite, where the phosphate undergoes further processing before continuing towards the port.

Fig. 48. An enclosed conveyor belt runs along the main road at Drumsite. The feeder, shown here, extracts the phosphate dust produced by the conveyor, which is also bagged and exported.

Fig. 49. The current conveyor system above the old railway incline, halfway up the hill between Settlement and Drumsite.

Fig. 50. The conveyor belt plunges towards the storage facilities at the port.

Fig. 51. Bags of phosphate dust in storage awaiting export.

Fig. 52. The pivoting steel cantilevers that load phosphate from the conveyor system directly into a ship’s hold.

Fig. 53. Phosphate dust is tacky and sticks to everything, eventually forming thick layers as seen here.

What immediately sets Christmas Island apart from other phosphate islands, however, is its relative size: approximately six times larger than Nauru and twenty-three times larger than Banaba. It also stands around six times taller than Nauru, reaching 361 meters above sea level to the west at Murray’s Hill, named after the Scottish naturalist, John Murray, who first agitated for the Crown to annex the uninhabited island in 1888. Following chemical testing of rock samples taken from one of its inshore reefs during the Challenger expedition in the mid-1870s, Murray concluded that Christmas Island was likely to contain large deposits of high-grade phosphate of lime. The Christmas Island Phosphate Company (CIPC) was eventually formed in London in 1897 with Murray as its chairman and mining was commenced two years later by 120 indentured laborers, yielding just ten tons of exported rock by year’s end.13 36,000 tons were exported in the following year and by 1906, 90,000 tons left the island for markets in Europe and Asia. By 1912, the significantly expanded industrial facilities were capable of processing up to 157,000 tons of phosphate annually, having surpassed a million tons in total exports in the previous year.14

Fig. 54. Detail of a 1908 survey depicting the CIPC’s phosphate facilities and company settlement west of Rocky Point in the north. Tramways, tanks and quarries are indicated in the areas around Phosphate Hill where the early mining activity was concentrated. John Murray, John D. Murray and C. W. Andrews, Running Survey of Christmas Island, Indian Ocean (Edinburgh: The Edinburgh Geographical Institute, 1908), National Archives of Australia, 1121/M.

Fig. 55. Steep hills, limestone cliffs and large Banyan figs are found everywhere on Christmas Island.

Fig. 56. Indentured Chinese coolies on Christmas Island c.1910 under the watch of the District Officer’s Sikh protective forces. National Archives of Australia, N29/1, 203206255.

Once again, a map of the island from the early twentieth century proves helpful in locating the original facilities constructed by the CIPC (figure 54). Climbing into my morose-looking hire car, a thoroughly exhausted Toyota Hilux, I ascend from the port at Flying Fish Cove past large cuttings in the limestone cliffs (figure 55), before eventually reaching Phosphate Hill in the north-east of the island, the car’s gearbox whingeing with every increase in the steep gradient of the road. There’s little to see other than a few non-descript phosphate pits, but the map invokes the story of the work that once took place here. As on Banaba and Nauru, the labor-intensive process of clearing the dense tropical jungle, removing the topsoil and ultimately extracting the phosphate rock required a large workforce in the initial stages (figure 56). To this end, close to 2500 Chinese laborers, indentured from the Sze Yap region of western Kwantung province and from Hainan Island, were contracted by the CIPC each year using the Singapore-based labor agent, Ong Sam Leong.15 An account of the working conditions on the island in the first years of the Company’s operation was provided by the Protector of the Chinese in the Straits Settlements, Lewis Clayton, who visited in 1900:

The phosphate is at present only being worked at and near the summit of Phosphate Hill. The coolies pick it up from the ground, where it lies in blocks, and throw it into iron trucks running down a slight incline to the head of a double line of rails which descend for a distance of about 500 yards […] The loaded trucks run right onto a wooden platform and the phosphate is then tipped out of them down ‘the shoot’. Coolies at the bottom again pick the stones up and place them in wooden trucks running to the water’s edge, which are emptied down a metal line ‘shoot’ into boats.16

In 1909, the system Clayton describes was refined with the introduction of “aerial trams” manufactured by Kerr Stuart in Liverpool, which transferred the phosphate along a cableway from the iron trucks used at Phosphate Hill into the drying sheds at the port. From here, the dried rock was pushed in carts along one of two elevated piers before being tipped into chutes by steam cranes and thereby loaded into the ship’s hold. In 1912, following sustained investment in capital works, the phosphate was loaded directly from the storage shed by newly erected conveyor belts (figures 57).

Fig. 57. The Tonan Maru under loading by the mechanized cantilevers in 1928. Christmas Island, National Archives of Australia, R32, CIPC 6/25A, 6446584.

Fig. 58. View over Flying Fish Cove showing Edinburgh Settlement, upgraded loading facilities, phosphate tip and the “coolie lines,” c.1908. Historical Photographs Relating to Christmas Island, 1905–1925, National Archives of Australia, N29/1, 203206254.

Fig. 59. Housing for European employees of the CIPC c.1910, Phosphate Hill. Christmas Island, National Archives of Australia, R32, CIPC 6/25A.

Fig. 60. The former Christmas Island Club overlooking Flying Fish Cove.

As was the case with the PPC’s contemporary operations on Nauru and Banaba, the racial stratification of labor within the CIPC was carried into the housing it provided for its employees. The company’s white officers resided in tropical bungalows initially built around Flying Fish Cove that overlooked the phosphate loading facilities and were strictly segregated from the workers’ areas (figure 58). The early houses in Edinburgh Settlement, as the residential area was known, boasted large verandahs, extensive eaves, shading devices, and stack ventilation in the steeply gabled roofs (figure 59). Each house, constructed from timber felled on the island, was raised on piers for increased ventilation and rose up to three floors depending on the occupant’s status within the company. After hours were spent at the Christmas Island Club where white company employees and their families mingled with members of the District Office—which upheld British rule on the island—over evening drinks. The building now stands boarded-up and deteriorating halfway up the cliff face above Flying Fish Cove, soon to recede entirely into the ravenous scrub (figure 60).

Fig. 61. Detail of a c.1908 map depicting the “coolie lines” running along what is now Gaze Road. The kongsi is show towards the beginning of the lines. “Aerial haulage” is shown in red, connecting the phosphate tip further up the hill to the storage shed and loading facilities on the coast. Plan of Flying Fish Cove Christmas Island, Map 1, Miscellaneous Collection Christmas Island Maps, National Archives of Australia, R175, Box 1, 33057600.

Fig. 62. The Mandors quarters, 1930. Christmas Island Housing, National Archives of Australia, R32/C25, 1749820.

Fig. 63. The Mandors quarters today.

On the other side of the CIPC’s loading facilities to the Edinburgh Settlement, running from Isabel Beach to Rocky Point, were the so-called “coolie lines”—initially, 25 by 35 feet raised timber dormitories that housed between fifteen and fifty workers each (figure 61). By 1908, close to forty new dwellings had been constructed, the walls from weatherboard and the roofs from double attap. The exteriors of the lines were tarred annually and the interiors were whitewashed every six months.17 These, too, were soon replaced by updated designs due to the rapid deterioration of timber in the tropical conditions. Outbreaks of beri beri, poor sanitation, crowded living conditions and industrial accidents led to a death rate of up to twenty-five percent among the indentured workforce in the early years of the Company’s activities on Christmas Island.18 To prevent revolt, the Singapore-based labor agent Ong—who received a percentage of the profit from the phosphate sold by the CIPC—employed so-called “Mandors” or foremen, promoted from among the indentured workforce and tasked with ensuring the profitability of their former peers (figures 62 and 63). In 1902, two Mandors were killed by laborers in protest against their punitive methods.19 To diversify his income from the island, Ong also opened a kongsi—a Hokkien term for an incorporated business—that sold food to workers at inflated prices to supplement the meagre rations provided by the CIPC, as well as arranging opium supply, prostitution services and gambling rings on the island.

Fig. 64. The railway to South Point under construction through thick jungle and over rough limestone in 1915. Christmas Island, National Archives of Australia, R32, CIPC 5/27A.

Fig. 65. What remains of the South Point railway today: an overgrown embankment running through dense stands of pandanus and along steep limestone cliffs.

Fig. 66. Ferns indicate disturbed ground on Christmas Island. Here, the embankment cuts through a former mining area, enabling the workers to load the phosphate carts from both sides of the railway.

Fig. 67. Remains of the crushing and loading facilities at the South Point settlement.

By 1914, the quarry initially worked by the CIPC on Phosphate Hill had been largely exhausted. Following the discovery of a large high-grade deposit in the area known as South Point, the Company undertook to construct an eighteen-kilometer railway, cleaved through thick vegetation along the rugged southern coast, which would connect the area to Flying Fish Cove (figure 64). Driving along the hand-built embankment today, all that remains are decommissioned steel electricity poles and a concrete waterpipe, stitched along the narrow track (figure 65). Former mining sites appear intermittently, their thick layer of ferns indicating disturbed ground (figure 66). The South Point railway was operational within six years, delivering a substantial increase in the rate of phosphate exported from Christmas Island into the early 1920s. A separate settlement gradually developed, complete with its own mining offices, sports facilities, hospital, barber, power station, gambling hall, police station, brothels and a temple—all arranged around the railroad and crushing plant. Bits and pieces of the town still remain after its demolition in the early 1970s (figures 67).

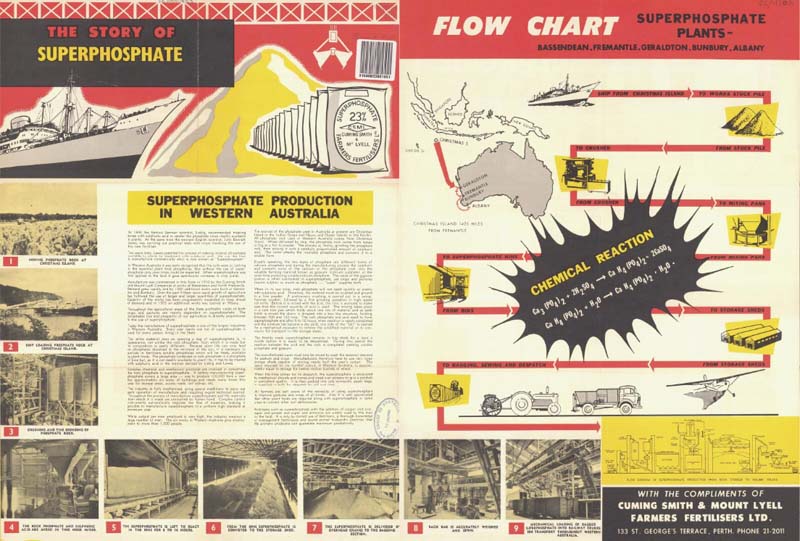

Fig. 68. Cuming Smith & Mount Lyell Farmers Fertilisers Ltd., “The Story of Superphosphate,” advertisement, National Library of Australia, c.1920, UApam 933.

Fig. 69. Flats built by the BPC in the 1950s along Gaze Road, Christmas Island.

Fig. 70. Housing built for BPC employees and their families in the 1960s along Gaze Road, Christmas Island.

Fig. 71. The former BPC bungalow in which I stayed while on Christmas Island.

Following the acquisition of CIPC by the Australian and New Zealand governments in the aftermath of World War Two, Christmas Island phosphate was almost exclusively shipped to Western Australia, whereas Nauruan and Banaban exports serviced the fertilizer industries on Australia’s east coast and New Zealand (figure 68). The BPC, from its headquarters in Melbourne, thus managed a sprawling extractive territory spanning four islands across two oceans, staffed by Australian, New Zealander and British engineers, technicians, managers, architects and executives who together controlled a substantial stake of the world’s supply of phosphate. Major expansion and modernization projects continued into mid-century, tightening the grasp of the Commission over every aspect of life on the islands: from schooling and healthcare to housing and recreation (figures 69 – 71). Building designs and mining technologies were recycled and adapted from island to island. Annual reports, inter-island conferences and routine audits by the commissioners ensured the entire operation was running as efficiently and effectively as possible. By the 1960s, the islands controlled by the BPC were heavily engineered terrains: comprehensively surveyed, efficiently organized into mining grids, scrupulously scraped back to their limestone foundations. By the 1970s, close to ninety percent of the surface of Banaba had been removed, displacing Banabans to Rabi Island in Fiji. Nauru was also deemed uninhabitable by the late 1960s and a failed attempt was made to relocate the Nauruan population to Curtis Island off the coast of Queensland. Australia purchased Christmas Island from Singapore in 1958, running the industry through the BPC into the late 1970s. Industrial action by workers seeking improved conditions and wage equality with Australia led to a Royal Commission in 1980, which concluded that:

The institutional framework within which Christmas Island operates is outmoded, discredited, and in many ways repugnant. […] The British Phosphate Commissioners (BPC) is an organization which has not adapted quickly enough to or willingly enough to the passing of the colonial era. […] The structure of the Government Administration on the Island, and much of the law that is in force, is more appropriate to a colonial possession than it is to a remote multi-racial mining community on Australian territory.20

A new company structure was introduced in response to the adverse findings of the Royal Commission until ongoing unrest and environmental activism led the new venture to declare the commercially unviability of the industry before entering into voluntary liquidation in 1987.

Fig. 72. Deteriorating former phosphate storage shed, Nauru.

Fig. 73. Former phosphate processing equipment, Nauru.

Where political solutions focused on neatly resolving the effects of close to a century of phosphate extraction on Nauru, Banaba, and Christmas Island, the pockmarked landscapes and deteriorating infrastructure left behind by the BPC and its commercial forebears immediately disclose the scale of human exploitation and ecological violence that the colonial bureaucracy attempted to conceal (figures 72 and 73). But this concealment was also a function of the infrastructure itself, which both physically connected the disparate places involved in the overall process of superphosphate production, while also severing—in the minds of consumers—the sites of phosphate extraction in the Indo-Pacific from those of its application on Australian soils. “As the farmer drives his drill across the paddocks at seeding time,” begins a 1936 article in the Adelaide paper The News, “or carts weighty bags of superphosphate from the nearest railway station, he gives little thought to the origin of that artificial manure which has done so much to increase the yield of his crops and pastures. At Port Adelaide, Wallaroo and Port Lincoln are busy chemical works that manufacture the fertilizer, but it is from mid-Pacific coral islands that the phosphate rock comes which is its chief component.”21 As Brian Larkin has argued, infrastructures work in precisely this way, preparing the ground for other things to act on the world while they themselves disappear from view: “their peculiar ontology lies in the facts that they are things and also the relation between things. As things they are present to the senses, yet they are also displaced in the focus on the matter they move around.”22 This mode of analysis has proved challenging for scholars of architecture, whose predilection generally remains to focus on buildings as isolated objects. Its benefit for this fellowship project, however, is to situate individual instances of spatial production—i.e., the buildings, jetties, railways, chutes, cranes, ships, and so on considered in this report—in relation to one another as elements of an extractive system that reorganized islands in the Indo-Pacific to fuel Australia’s particular brand of racial capitalism (figure 74).

Fig. 74. Propaganda for promoting white immigration to Australia as part of the Million Farms Campaign, which used pamphlets and political lobbying in the early 1920s to aggressively tout what it described as “the biggest biological experiment the world has ever known – White Australia.” Joseph Carruthers, The Great Objective: How the Million Farms Campaign is Faring (Sydney: Million Farms Campaign Committee, 1921), 15.

Fig. 75. One of the many Taoist temples on Christmas Island.

Fig. 76. A wheatfield in the Wimmera Mallee, c.1935. State Rivers and Water Supply Commission, Wimmera Region, State Library Victoria, RWP/1855.

The notion that Australia was itself an imperial power—and not simply a settler-colonial product of British empire—remains marginal at best in the popular consciousness. On Nauru and Christmas Island, however, the physical evidence of Australian imperialism remains irrefutably on display. Australia’s empire was not the result of the direct colonization, annexation or invasion of territory; rather, it was amassed gradually through the increasing bureaucratization of political authority on islands of value to its economic development. Phosphate is one vector in this broader history of extractive sovereignty, revealing the modes and techniques through which Australian imperialism became instantiated and eventually entrenched in once foreign places. Walking along Gaze Road on Christmas Island—named after Harold Gaze, General Manager of the BPC—past the Chinese Literary Association, the Chinese Cultural and Heritage Museum and Tai Pak Kong, the Taoist temple, I contemplate the complex cultural histories engendered by the colonial phosphate industry (figure 75). In particular, I consider what I at first regard as a glaring hypocrisy: that during the period of the White Australia policy, which officially commenced in 1901 and lasted into the 1970s, white farmers in Australia were entirely dependent on the phosphate mined by Chinese, Japanese, Pacific Islander, and South Asian workers in the Indo-Pacific to sustain their highly politicized form of living, itself premised on Indigenous dispossession (figure 76). By the time I arrive back at my accommodation, my thoughts have corrected themselves: far from being hypocritical, white Australia’s expropriation of Indigenous land, foreign resources, and non-white labor was deliberate, engineered, and essential to its viability. White supremacy in Australia was in fact contingent on Australian imperialism and vice versa; Australian empire in the Indo-Pacific was enacted on the basis of the former colonies’ sovereign independence as a white ethnostate. These co-dependencies were as much infrastructural as they were political and economic: where legal status shifts, bureaucratic and spatial form accrete. In securing the raw material upon which the extension of Australian settler-colonialism depended, the phosphate industry developed on Christmas Island, Banaba, and Nauru therefore played a decisive role in stabilizing the extra-territorial limits of Australia as both a biological and a political community.

1 Cait Storr, International Status in the Shadow of Empire: Nauru and the Histories of International Law (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 90.

2 On the labor trade for the phosphate industry on Nauru and Banaba, see Ralph Shlomowitz and Doug Munro, “The Ocean Island (Banaba) and Nauru Labour Trade,” Journal de la Société des océanistes 94 (1992): 103–117.

3 Ben Doherty, “Australia’s offshore detention is unlawful, says international criminal court prosecutor,” The Guardian, 15 February 2020 (accessed 5 December 2023), https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/feb/15/australias-offshore-detention-is-unlawful-says-international-criminal-court-prosecutor.

4 Paul Karp and Tory Shepherd, “Nauru offshore processing to cost Australian taxpayers $485m despite only 22 asylum seekers remaining,” The Guardian, 23 May 2023 (accessed 5 December 2023), https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/may/23/nauru-offshore-detention-immigration-processing-to-cost-australia-485m-22-asylum-seekers.

5 Storr, International Status in the Shadow of Empire, 25. Emphasis added.

6 Ibid., 36.

7 On the history of Banaba, see Katerina Teaiwa, Consuming Ocean Island: Stories of People and Phosphate from Banaba (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2014).

8 Storr, International Status in the Shadow of Empire, 34.

9 Ibid., 33. See also Cait Storr, “‘Imperium in Imperio’: Sub-imperialism and the Formation of Australia as a Subject of International Law,” Melbourne Journal of International Law 19, no. 1 (2018), 336.

11 See Raymon E. Reyes Jr., “Nauru v. Australia: The International Fiduciary Duty and the Settlement of Nauru’s Claims for Rehabilitation of its Phosphate Lands,” New York Law School Journal of International and Comparative Law 16, no. 1+2 (1996): 1–54.

12 A. N. Gray, “Table No. 166—Oceania—Shipments from Ocean/Nauru Islands 1921–1929. Bill of Landing Weights (Metric Tons),” in Phosphates and Superphosphates (London: International Superphosphate Manufacturers’ Association, 1930), 263.

13 Harold L. Burstyn, “Science Pays Off: Sir John Murray and the Christmas Island Phosphate Industry, 1886–1914,” Social Studies of Science 5, no. 1 (1975), 25–26.

15 David Jehan, Shays, Crabs and Phosphate: A History of the Railways of Christmas Island, Indian Ocean (Melbourne: Light Railway Research Society of Australia Inc., 2008), 14–15.

16 Quoted in Jan Adams and Marg Neale, Christmas Island – The Early Years, 1888–1958 (Canberra: Bruce Neale, 1993), 36.

17 Fran Yeoh, “The early coolie houses on Christmas Island,” Christmas Island Archives, accessed 15 December 2023, https://christmasislandarchives.com/coolie-houses/.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top