-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

U.S. Southwest: Back to the Future

Jul 14, 2025

by

Francesca Sisci, 2025 recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Francesca Sisci is an architect and adjunct professor at Polytechnic of Bari, Italy. She has a PhD in Architectural Representation and her approach of research is distinctive in its integration of multiple disciplines, including art history, architectural theory, and photography. She focuses on exploring aspects of visual perception and how these can be translated into images.

As a recipient of the 2025 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Sisci is exploring the feminine imaginary as it applies to architecture from ancient to contemporary structures. She will explore this important question by trying to identify the types of architectural spaces that in different ways are connected with the female gender. In the course of a 6-month itinerary she will visit sites in Sardinia, Malta and Gozo, Türkiye, Crete, UK and Ireland, Norway, Greenland, United States, and Mexico. All photographs are by the author.

The light that fills the New Mexico desert is intense. It washes out colors and hits the eyes with such force that they narrow into a thin slit. I’ve just arrived in Albuquerque. In my backpack is All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy, and from here, my journey begins—into the lands of the American Southwest.

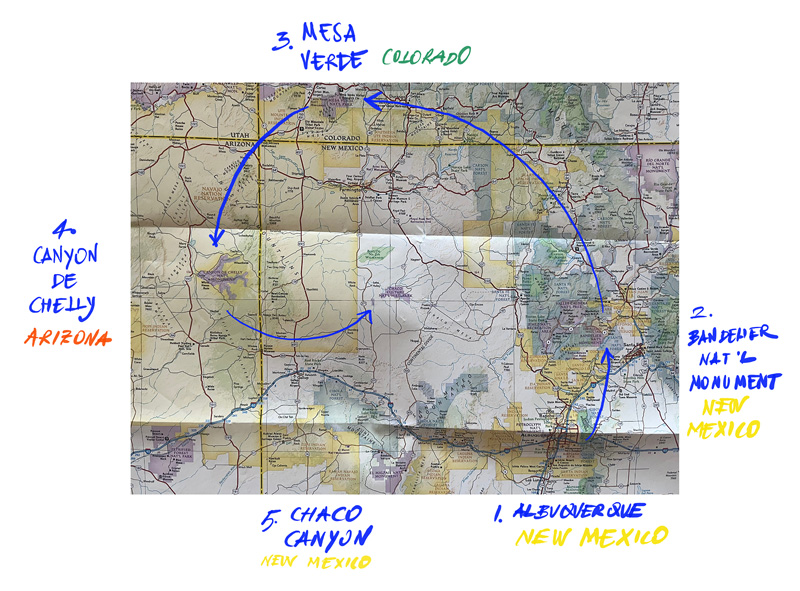

My plan is to move through the Ancestral Area, a region that stretches across the Four Corners states: New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, and Utah (fig.1). What I’m looking for are the cliff dwellings and the kivas—architectures that stand as witnesses to an ancient world. But due to a kind of crack in the space-time system—caused by the fact that America was "discovered" only in 1492—these structures are considered prehistoric sites despite a certain proximity in time to our present

Fig.1 My Route Through the Ancient Pueblo Lands

My first impression of the city leaves me disoriented. It’s the first time I find myself in a truly American city—New York doesn’t really count. Albuquerque is in the South, and even my past visits to cities along the East Coast don’t help much here. Slowly, I start to understand the logic of it all. An endless spread of homes, still and worn under the hot sun, stretches out before me. There’s no visual of spatial tension, no variety in form. Everything is laid out on a grid. Everything is accessible by car. A sea of external AC units blasts waves of hot air that distort the view—as if a single mirage has settled across the top of the city.

Life here happens in the car. The drive-thru options are impressive—you can order any kind of meal or drink, even withdraw money. The road is what stitches together otherwise separate elements: homes, shops, offices, churches, motels, gas stations, supermarkets, hospitals… and then again: homes/road – stores/road – offices/road – churches/road – police stations and gas stations/road… and on and on in an infinite loop. Giant signs manage the flow of traffic, guiding people through this vast territory, giving a false sense of closeness. But hey, all you need is a 30-minute drive to get wherever you want—it's right around the corner!

After experiencing this physically—before even thinking about it—I feel validated in my decision to rent a pickup truck right away. I’ve become part of the landscape, fully immersed in the local culture of dominating the environment before it dominates you. And yet, I can’t help but wonder: how many days on horseback would it have taken to travel from Albuquerque to Taos?

In New Mexico’s capital, I decide to visit the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center—my first real contact with Native American history. This isn’t a museum, but a living space where everything is focused on preserving, sharing, and passing down the core knowledge and values of Native North American culture. If it were a museum, it would be about the past. But the story that flows through the center's exhibits speaks of a fragile present, striving toward a stronger future for Indigenous communities. This sense of timelessness unsettles me. There’s no narrative built around dichotomies—like before and after the “discovery” and colonization of America. Nor is it structured around historical progress, like "a thousand years ago we did this, and now we do that." As I walk through themed rooms and display cases—crafts, songs, languages—I realize that the message is clear and constant: this is who we are, who we have always been, and who we still are. What’s happening out there doesn’t change that.

The vast majority of the captions accompanying the display cases speak in the present tense. They explain how people live today, what they believe in, and how they continue to honor their ancestors. I begin to understand that my original idea—of looking only for the past—is flawed, or at least incomplete. There is a Native American people today, living on and inhabiting the very lands I’m about to cross. They are made up of many distinct communities, together forming the Tribal Nations: the tribes who have always lived in this country, long before anyone else, and who have survived.

One map shows that many pueblos are still inhabited today, especially along the Rio Grande.

I come to realize that Indigenous reality follows two parallel, coexisting paths: the ancient settlements built deep in the canyons, later abandoned, and

the pueblos still lived in today—marked by adobe constructions, the legacy of contact with Spanish conquistadors.

At that point, I decide that one cannot be understood without the other. But integrating the living pueblos into my itinerary turns out to be more complex than expected. I discover that not all of them can be visited freely. In many cases, it’s necessary to contact the tribal chief in advance and obtain permission. And even then, photography, video, and sketching are strictly prohibited. Above all, it is absolutely forbidden to walk through the enclosed space in front of the church—built after the arrival of the Spanish—out of respect for its sacred nature, and the deep legacy of the land under and around. Taking in all this information—where I begin to glimpse the first cracks in the complex coexistence of Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities sharing the same land—I don’t feel discouraged. On the contrary, I feel even more strongly that it’s essential to see what has survived in these pueblos. For now, though, I turn my attention to telling the story of the ancient Anasazi villages, preserved in the canyons' deep gorges.

The word Anasazi, in the Navajo language, means “the ancient enemies,” and today it is considered no longer appropriate. Scholars and descendants alike now prefer the term Ancestral Peoples to refer to those who lived along the Rio Grande and more broadly in what is now Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona.

This shift in terminology helps explain how the memory of this civilization is still carried today by its descendants. The Ancestral Peoples inhabited the American Southwest between the years 100 and 1300, and for the communities living in the region today—particularly the Zuni and Hopi—they represent their direct ancestors. This creates a striking sense of closeness between what we call "prehistory" and the present. Just seven centuries separate a world without writing from the age of electric vehicles. Seven hundred years in human history is less than the blink of an eye—we have been on this planet for over six million years.

From Albuquerque, I head northeast toward Frijoles Canyon, home to Bandelier National Monument. Here, the earliest traces of human presence date back over 11,000 years, but the first established Indigenous settlement is believed to have been built around the year 1100 and abandoned around 1400. The famous cliff dwellings appeared about a century later.

To visit the various archaeological sites, I follow a loop trail. The first stop is the Big Kiva. Just beyond it, the circular ruins of Tyuonyi village come into view—its layout forming almost a perfect ring. Further along the path, the Long Houses begin to appear on the canyon’s northern wall.

In the soft volcanic tuff, the Ancestral Puebloans carved evenly spaced holes—consistent in size, height, and distance—to hold beams that supported wooden flooring. The side and back walls were built using roughly hewn stone blocks. The Long House complex eventually grew to around 300 rooms, some of which extended up to three stories high. For this reason, Bandelier’s Long House is considered the most complex settlement on the Pajarito Plateau.

It’s easy to understand why this type of construction made sense—climate being one key factor. The canyon wall provided natural support for the structures and offered insulation against the elements. Looking at it today, the cliff face along Frijoles Creek feels like a page still holding the markings of a story—one that may seem distant but is in fact incredibly close (figs. 2, 3, 4). Shared walls and flooring systems remain clearly legible, as do petroglyphs and openings wide enough to have once formed full interior rooms.

Fig. 2 Wall of the Long House, Bandelier National Monument. The holes for the poles that formed the roof beams are clearly visible, along with the carved-out rooms in the canyon wall, which are accessed through openings leading to interior chambers.

Figs. 3, 4 Wall of the Long House, Bandelier National Monument. In the lower section, the ruins of dwellings built against the rock face are still visible.

What strikes me about the Long Houses is the blend of spontaneity and pragmatism behind their design. They don’t feel improvised. They show evidence of careful planning and a deep understanding of available materials and environmental conditions.

As I observe, I find myself thinking that humans have always performed to the highest technical level available to them in their given moment. So then, compared to what can we really define something as archaic, modern, or contemporary? That question travels with me now—a quiet companion on the long drives from one destination to the next, as endless landscapes drift past my car window. Mile after mile of desert stretches out before me as I head north, eventually crossing into the San Juan National Forest, on my way to Mesa Verde, Colorado.

My understanding of these places, before actually traveling through them, was based largely on the extraordinary images captured by Timothy O’Sullivan and Ansel Adams. Their documentation of the American Southwest in general—and of specific sites like Cliff Palace in Mesa Verde or the White House in Canyon de Chelly—served both as a guide and as inspiration for me. The evocative power of those photographs holds the very essence of why I set off on this journey. Cross the Rio Grande and pass through forests, to find snow right after the desert, to stop at the Mother Spring in Pagosa, to pass the great ranches along the road… finally, a road that doesn’t divide like it does in cities but instead connects distant places—each with a deep, ancestral meaning (figs. 5, 6, 7). A road was once a path, and I’m certain it has been walked millions of times, in long days under the sun or beneath clouds so low they seem to graze the earth.

Figs. 5, 6 Views of the Rio Grande Gorge

Fig. 7 Route 84, Colorado

As at Bandelier, my arrival at Mesa Verde is marked by the presence of rangers guarding the park. This too is managed by the federal government, which ensures a high level of service and accessibility, including guided visits into the canyons. Everything is well organized, and for those who can’t or prefer not to hike, there are loop roads with clearly marked stops that offer stunning overlooks into the gorges below. This is also a form of drive through service somehow… not for fast food but for the fast pace of history.

At Mesa Verde, the first buildings date back to 600, but it was between 1100 and 1300 that the spectacular cliff dwellings reached their peak. Around 1300, however, the inhabitants left the site, likely driven away by changing climate and dwindling resources. The Spruce Tree House is breathtaking. Tucked into a narrow alcove carved into the canyon wall, the sandstone buildings both blend into the landscape and assert their presence. They are subtle and bold—at once unexpected, yet perfectly in place. Somehow incongruent and completely harmonious at the same time (figs. 8, 9).

Fig. 8, 9 Spruce Tree House, plus a detail from the surrounding area, Mesa Verde, Colorado

The housing units are arranged organically, rising one or two stories high, depending on how much space the rock shelter allows. They make use of the in-between space, the interstice. From holes in the ground between the volumes, which almost resemble a central square, the wooden beams of ladders emerge, leading down into the kivas. These are underground spaces—circular in shape—unlike the quadrangular form of the living quarters. Access is only possible through a hole in the ceiling, reached by a wooden ladder that isn’t fixed but removable. Their use was strictly ceremonial (fig. 10).

Fig. 10 Jesse Nusbaum, Cerimonial Kiva (Alcova), Bandelier National Monument, New Mexico. Photograph exhibited at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Cente in Albuquerque, courtesy of the Palace of the Governors Photo Archives.

The access paths leading down into the canyon are closed due to a weather alert, and the rangers have made the tough call to suspend hikes. No matter—I set off by car along the scenic loop and stop at every overlook I can reach: Sun Point Cliff Dwelling, House of Many Windows, Balcony House… Every time, I’m amazed by the height at which the dwellings were built. The canyon drops sharply beneath them, and yet the risk of falling must have seemed far more acceptable than staying up on the mesa, exposed to harsh weather and wild animals.

For a moment, I imagine an unimaginable world—one of brilliant starry skies, of endless silence broken only by the distant howling of coyotes, of winds whipping through the low shrubs on the mesa, of small fires lit to warm up or cook food, and the constant need for shelter—for a tree, a massive boulder, or the heart of the earth: the canyon itself.

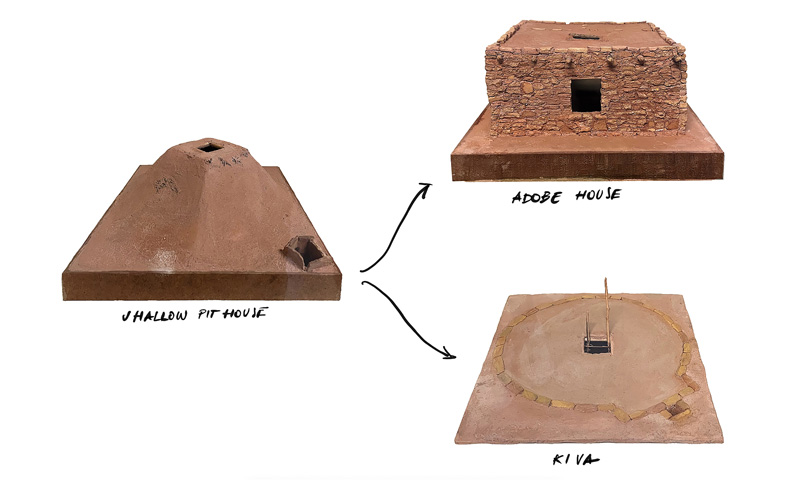

I head to the Visitor and Research Center to ask for more information and to visit the small museum. This one is a museum, complete with display cases housing dated artifacts, each carefully labeled with explanations. The exhibit that grabs my attention most is titled The Development of Pueblo Architecture. Through a series of three-dimensional models, it traces the evolution of the typical dwelling known as the pit house, first appearing around the year 400.

This early structure was partially dug below ground level, creating a semi-subterranean room, later covered by a truncated pyramid-shaped roof with a central opening. Originally, these spaces served both as homes and ceremonial sites. Over time, they evolved into two distinct types: the adobe house, which became the primary form of residential architecture, and the shallow pit house, reserved for religious ceremonies (fig. 11).

Fig. 11 From the Shallow Pithouse—the earliest type of dwelling—to the Adobe House and the Kiva. Scale models displayed at the Mesa Verde National Park Visitor and Research Center.

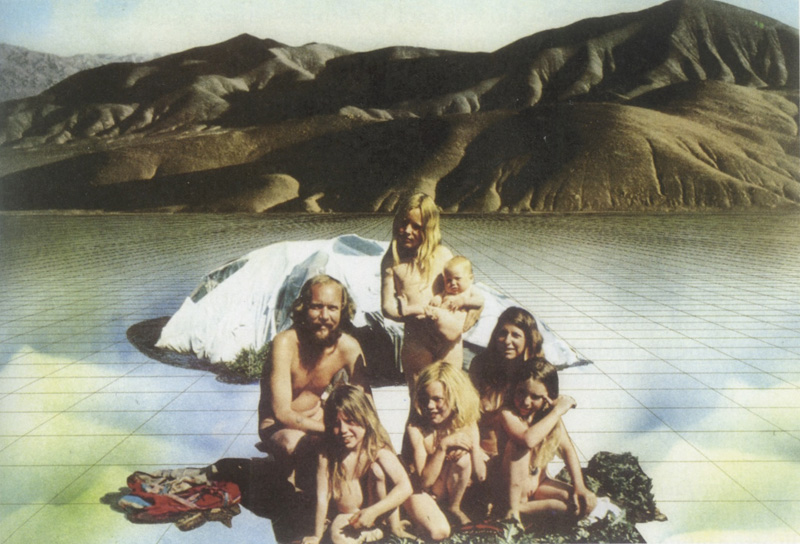

What comes immediately to mind is The Camp, one of the collages from The Fundamental Acts series by the radical Florentine group Superstudio (fig. 12). It was the 1970s, and Italy—like much of the Western world—was being swept up by an economic boom. Consumerism, or rather superconsumerism, had become the new rule. Life, along with its older meanings, was being radically redefined.

In that social landscape, what would architecture become once it lost its role as a mediator between humans and their environment? According to Superstudio: nothing—or rather, a supersurface. An architecture without form or scale. A network of information flowing across the land, accessible through evenly spaced ground connections—power outlets for sophisticated tools designed to free humans from labor, encouraging a return to nomadism and a life devoted to listening to oneself in a boundless silence.

Fig. 12 Gli Atti Fondamentali, Vita (Supersuperficie), L’accampamento. Superstudio 1971. Collage (The Fundamental Acts, Life (Supersurface), The Camp).

I leave Mesa Verde just as the sun begins to set, stretching long shadows across the canyon walls. The light from the west tells me it’s time to get back on the road and head toward Arizona. I begin the descent from the plateau—over 7,000 feet high—and slowly, almost without realizing it, I pass from forest back into desert, crossing the invisible threshold of the Four Corners. My destination is Chinle, the town closest to Canyon de Chelly. I take my time—more than I technically need—because the Arizona desert has pulled me into another dimension. Nothing I know feels anything like this place (fig. 13). I drive for hours along endless straight roads, interrupted now and then by gusts of wind that blow orange sand across the black asphalt, glowing in the low sun.

Fig. 13 Route 191, Arizona.

Along the way I see scattered, improvised houses—some built, some brought here, some simply imagined into existence. They look like they fell from the sky, spaced miles apart from one another, but they’re clearly lived in—or were at some point. The frequent school bus stop signs are proof of life.

In the desert, everything looks still, everything seems to be waiting for something to happen. But the truth is, life in the desert moves—just in ways that are invisible.

Arriving in Chinle isn’t just reaching my next destination. It’s also my first true moment of contact with the Navajo people. I’ve entered the largest reservation in the United States: the Navajo Nation.

Here, the road returns to being a kind of barrier—too wide, too fast, too unwalkable. The logic of the drive-thru is back again: fast food joints, solitary buildings, sprawling motels. I pass a large juvenile detention center. A wave of questions floods my mind—many probably naïve—and I feel, for a moment, unprepared to understand the depth of the cultural colonization at play here. A colonization from which, in many ways, there was simply no escape.

Canyon de Chelly is managed a bit differently from the other national monuments I’ve visited. The Navajo people retain ownership of the land, which means that entering the canyon requires finding a local guide. That’s how I meet Richard, my Navajo guide. We set off just after noon. Richard starts telling me about the canyon—not like an archaeologist would, or even like a trained tour guide. He doesn’t share dates or textbook facts. He tells me about his life—about when he was a child and used to play in the canyon with his friends.

“My mom didn’t want us to go,” he says. “That’s where ancestors are buried—you don’t play on their graves.”

“We used to go on foot,” he adds. “I know all the places where you can climb down from the mesa into the canyon.”

I can’t help but ask him what life in the desert is like—how people get by. He says, “You know, at a certain point we just needed a place we could call home. We came here, and this became our home. Some people still live down in the canyon.” So I ask, "So, how do you like it here? Are you doing okay?". He says, "Most people leave this place and head to Phoenix for work. I stayed because I wanted to be close to the canyon."

We reach the White House after about an hour of driving. The red sandstone cliffs rise over 600 feet against the brilliant blue sky. In the clear light, among the scattered vegetation, a small group of wild horses moves toward us, calm and unhurried (fig. 14).

Fig. 14 Canyon De Chelly, Wild Horses.

The Anasazi ruins here are arranged on two levels: one on the canyon floor and the other tucked into a rock shelter just above (figs. 15, 16). You can’t get too close—there’s a boundary you can’t cross. The land the White House sits on is private. It belongs to a woman who lives nearby, in a completely self-sufficient home. She produces her own energy with solar panels, grows her own food, tends her trees, and keeps reserves of water.

The White House was built around 1050 and was inhabited until about 1300. The architecture is divided between dwellings and kivas, and once again everything is built from the very same earth on which it stands. But the image we see today isn’t the one people would have seen in the past—back then, everything was coated in plaster… white plaster. I try to imagine it for a moment, and the visual impact must have been even more striking. Small outposts built into and carved from the natural fissures in the rock can be seen everywhere (Figs. 17, 18).

Figs. 15, 16 White House Ruins, Canyon De Chelly, Arizona.

Figs. 17, 18 Canyon De Chelly. The architecture takes advantage of the crevices and natural fissures in the rock.

We stay in the canyon for a long time. Richard speaks to me in his native Diné language and explains how some of their words are nothing more than phonetic transpositions of sounds—onomatopoeias transformed into meaning. His stories carry me into a time that feels impossible to place.

He has long hair, a necklace of raw turquoise stones, a cowboy hat, and boots. And judging by the calluses on his left hand, he is a cowboy. The sand here is so fine it feels like powder, slipping off the tips of his boots with every step. In that moment, I regret not having asked him to take me through the canyon on horseback—the canyon where he grew up. Simply being there at horse pace, listening to the sound of the wind as it moves along the rock walls, would have been enough.

Before leaving Chinle, I decide to return to the canyon one last time—this time by following the road that traces its perimeter along the mesa. I make my way to Canyon del Muerto.

I remember Richard telling me that, for the Diné, the canyon isn’t defined by names like we use on maps. To them, it’s divided in two: a masculine side and a feminine side. Canyon de Chelly, fertile and welcoming, is the feminine part—a symbol of Mother Earth. Canyon del Muerto is the masculine side.

When I arrive, I look down into the canyon and see cows grazing, their calls echoing between the walls and rising up toward me. Down there, the land is cultivated, dotted with trees in a bright, vivid green (figs. 19, 20). I don’t know why, but I suddenly feel that if paradise on Earth ever existed—somewhere, long ago—it must have looked something like this. Maybe it’s here that Changing Woman, the sacred deity of the Navajo people, was born from a ray of sunlight and a piece of rainbow.

Figs. 19, 20 Top view of Canyon del Muerto.

Leaving Arizona fills me with a quiet melancholy. The desert rushing past my window changes quickly as I head toward New Mexico. My destination is Chaco Canyon—just south of Mesa Verde and roughly halfway between Bandelier and Canyon de Chelly. Getting to the famous Pueblo Bonito isn’t easy. The road turns to dirt and stays that way for miles (fig. 21). But I don’t mind; I still have a lot to process—thoughts, impressions, sensations. It almost feels intentional, this slow-moving trail, as if it’s trying to strip you down and prepare you for what lies ahead. Chaco Canyon feels very different from the other places I’ve visited. It’s more like a wide, open valley, cradled by cliffs that never rise more than 400 feet. The impact is less dramatic, at least visually, but not less meaningful.

Fig. 21 Road to Chaco Canyon, New Mexico.

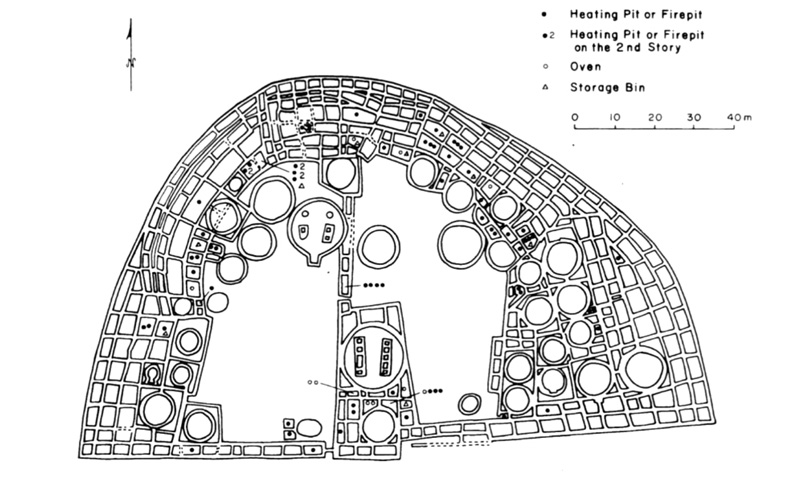

Pueblo Bonito means “beautiful town,” and it must have looked that way to the Spanish conquistadors who named it. Like many other monumental sites in the region, it was built by the Ancestral Puebloans, and was occupied from around 828 to 1126 AD (figs. 22, 23). Its exact function is still debated. The complex includes roughly 800 rooms spread across three acres, with some residential structures reaching up to five stories high (fig. 27). The layout curves in a semi-circle around more than 30 kivas, including the Great Kiva at the center (figs. 24, 25).

The most widely accepted theory today is that Pueblo Bonito was a major trade hub. Some rooms clearly served as storage spaces, and archaeologists have found remarkable items inside—cacao from Mexico, seashells from the Gulf of California and the Pacific Ocean, finely decorated pottery and containers, obsidian tools, large stores of maize, and tens of thousands of turquoise stones.

As we’ve already seen, the architecture here is made from sandstone, mortar, and wood. The rooms are arranged around what we might call a plaza, which houses the kivas—those sacred ceremonial spaces (fig. 26).

Fig. 22, 23 Chaco Canyon walls.

Fig. 24 Plan of Pueblo Bonito, showing its distinctive D-shape with a central plaza, multiple kivas, and over 600 rooms organized in a semicircular layout.

Fig. 25 The Great Kiva of Pueblo Bonito, an impressive ceremonial structure at the heart of Chaco Canyon, reflects the architectural and spiritual sophistication of the Ancestral Puebloans.

Fig. 26 View of the Central Area of Pueblo Bonito.

This layout repeats across all Ancestral Puebloan settlements, with slight adaptations to the local terrain. That’s no coincidence. Architecture always reflects, in some way, the society that produces it. In many Native North American cultures, women held a central role. Lineage was matrilineal: women owned the home, which was passed down from mother to daughter. At Pueblo Bonito, this isn’t just a theory—it’s been found in the soil itself. In Room 33, archaeologists uncovered several burials of both men and women, nine of whom shared the same maternal lineage, as shown by mitochondrial DNA analysis. This points to a matrilineal dynasty that lasted for over three centuries. The house, then, was not just a shelter—it was a practical and symbolic extension of the woman’s role in society, a role echoed even more explicitly in the design and meaning of the kivas.

Fig. 27 Interior of the Dwellings of Pueblo Bonito.

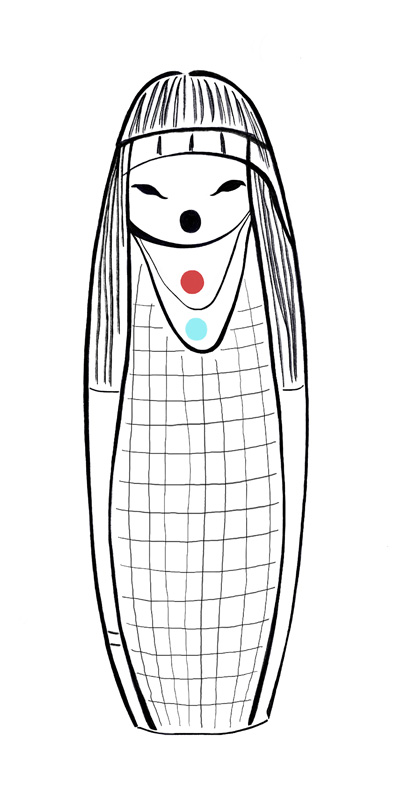

In the mythology of the Southwest, the Corn Mother is a foundational figure (fig. 28). Through her sacrifice, she gives birth to maize, the sacred crop that sustains life. She embodies creative feminine power—a maternal force linked to fertility, nourishment, growth, and the continuity of life.

The cult of the Corn Mother and the kiva are deeply intertwined in the cosmology and spiritual practice of the Ancestral Puebloans. A kiva is far more than an architectural space; it is a sacred chamber, a physical and symbolic portal to the underworld

and to ancestral forces. Every part of a kiva echoes the ancient belief that the ancestors emerged from deep within the earth, from the womb of the Great Mother. That’s why each kiva is built partially underground, and connects to the surface

through a small opening known as the sipapu—a symbolic birth canal.

To descend into a kiva is to enter the womb of Mother Earth.

We have been, for so much longer, what we have now forgotten. And we’ve been, for such a short time, what we have invented. I can’t help but wonder—has our memory truly disappeared?

Fig. 28 My Sketch of the Corn Mother Fetish.