-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

The prestigious H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship allows a recent graduate or emerging scholar to study by travel for one year while observing, reading, writing, or sketching. Fellowship recipients are required to document their travels through monthly posts on the SAH Blog.

2025 Amalie Elfallah

2025 Francesca Sisci

2024 Michele Tenzon

2024 Stathis G. Yeros

2023 Jasper Ludewig

2023 Annie Schentag

2022 Anne Delano Steinert

2022 Adil Mansure

2019 Sundus Al-Bayati

2018 Aymar Mariño-Maza

2018 Zachary J. Violette

2017 Sarah Rovang

2016 Adeyemi Akande

2015 Danielle S. Willkens

2014 Patricia Blessing

2013 Amber N. Wiley

2025 Recipients

‘Ghibli,’ a Libyan ‘Desert Wind,’ Lost in Translation Among Stone, Steel, and Speed

Sep 25, 2025

by

Amalie Elfallah, 2025 recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Amalie Elfallah is an architectural-urban designer from the Maryland–Washington D.C. area, which she acknowledges as the ancestral and unceded lands of the Piscataway-Conoy peoples. As an independent scholar, her research examines the socio-spatial imaginaries, constructions, and realities of Italian colonial Libya (1911–1943). She explores how narratives of contemporary [post]colonial Italy and Libya are concealed/embodied, forgotten/remembered, and erased/concretized.

As a recipient of the 2025 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Amalie plans to travel along the eastern coast of the United States before departing for Italy, China, Albania, Libya, and the Dodecanese Islands in Greece. Her itinerary focuses on tracing the built environment—buildings, monuments, public spaces, and street names—linked to a selection of Italy’s former colonies, protectorates, and concessions from the early 20th century. *All photographs are her own except otherwise noted. Some faces have been blurred solely to respect the people who give scale and context to the buildings and places she traveled.*

This writing weaves together my time in Italy. I am deeply grateful for the hospitality I encountered in every city and town I visited—from as north as Dro to as south as Syracuse. Thank you especially to SAH peers, colleagues, friends, and strangers who enriched my journey and reflections. Although I was unable to travel to Libya during my fellowship as originally planned, this piece gathers reflections that I hope to connect in the future.

_____________________________________________________

The name Ghibli is most commonly associated with Studio Ghibli (スタジオジブリ), the Japanese animation studio whose legacy has been manipulated by AI’s “Ghibli-style” imagery. The machine-generated drawings—created with a typewritten prompt and a single click—sharply contrast the studio’s hand-drawn films that unfold profound life-lessons. In the documentary “The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness” (2013), co-founder Hayao Miyazaki discusses the studio’s formation in the 1980s, casually recalling, “Ghibli is just a random name I got from an airplane.” But names, especially those that travel, rarely arrive in new places without being redefined.

In Libya, ‘ghibli’ (غبلي) is known as a “sandstorm” or a “desert wind blowing from the south.” Across some parts of the Sahara, ‘ghibli’ also refers to the “wind coming from Mecca,” deriving from the classical Arabic word ‘qibla’ (قبلة), meaning “direction.” By the late 1930s, ‘ghibli’ was Latinized—rather, Italianized—when the name was affixed to a military aircraft engineered by Gianni Caproni. The Caproni 'Ca. 309' Ghibli, according to Italy’s aeronautical military archives, was a “reconnaissance and liaison” aircraft utilized in Italy’s “North African colonies.” A word once referring to a natural atmospheric phenomenon was appropriated and attached to an instrument of war, transforming wind into steel and returning its name as a weaponized gust. Was Studio Ghibli’s title drawn from the wind itself, or from the machine that carried its name?

Fig. 1 – Propeller-shaped monument honoring aeronautical engineer Gianni Caproni, Arco, Italy

Fig. 2 – Garda Mountains and the Sarco River in Arco, Trentino-Alto Adige, Italy

Fig. 3 – Palazzo dell'Aeronautica Militare (c. 1938-41), Milan, Italy

Fig. 4 – Scene transition featuring the characters of Gianni Caproni and Jiro Horikoshi, ‘The Wind Rises’ (2013) by Ghibli Studio

I visited the monument honoring Caproni as a ‘Pioniere dell’Aeronautica’ in Arco (Fig. 1) while cycling along the paved path in the northern region of Trentino. The scenery unfolded beneath Ghibli-like clouds as I passed through the towering Garda Mountains (Fig. 2). It is easy to see how this breathtaking landscape inspired dreams of flight, especially for Caproni, who came from the region and later tested countless ambitious projects, such as a 100-passenger boat airliner. In reality, Caproni’s company significantly contributed to Italy’s Royal Air Force during military campaigns in Eritrea, Ethiopia, Libya, including across the Adriatic and Aegean Seas a century ago. As an architecture student at Politecnico di Milano, I had never considered the histories behind the marble façades and rationalist forms I passed by bike around Città Studi, like the Palazzo dell'Aeronautica Militare built in 1938 (Fig. 3). I overlooked the symbolism on the facade: the gladius sword, the propellers over the “M,” and a helmet resembling that from ‘Gladiator.’ The “Romanità” on the façade—so proudly displayed—escapes one’s notice just as everyday traffic insulates the hidden memory of Piazzale Loreto.

Studio Ghibli predominantly recasts Caproni as a reflective and visionary character in the animated film ‘The Wind Rises’ (2013). The first fictional encounter appears in the dreams of Japanese aeronautical engineer Jiro Horikoshi when Caproni leaps from a moving plane bearing the tricolor flag and lands beside a young Horikoshi as aircraft fly overhead. “Look at them,” Caproni says. “They will bomb the enemy city. Most of them won’t return. But the war will soon be over.” From a scene of destruction, the dream shifts to a passenger plane gliding past rolling hills beneath Ghibli’s iconic clouds. “This is my dream. When the war is over, I will build this,” Caproni declares. Inside, elegant curves and brightly upholstered seats furnish the interior (Fig. 4). “Magnificent, isn’t she?... Instead of bombs, she’ll carry passengers.” Caproni’s practice—designing machines for both war and transit—reveals how design moved between industrial cultures and civic life, often in tandem with the Italian Futurist movement.

Caproni’s practice most definitely shaped innovation in civic mobility post-WWI, which also echoes post-WWII innovations like Gio Ponti and Giulio Minoletti’s Arlecchino train (c. 1950s). At this year’s Salone del Mobile, the Arlecchino became the backdrop for the Prada Frames 2025 symposium at Milan’s Central Station. As curator Formafantasma noted, the train’s “exterior was informed by naval aerodynamics,” reflecting Italian design culture from fascist-era modernism and rationalism. The symposium also took place in the station’s Padiglione Reale, once reserved for royalty and fascist officials. Under the theme In Transit, it addressed “the complex relationship between ecology and design,” echoing the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale’s call for “decolonization and decarbonization.”

In practice, these venues' grandeur risked turning environmentalism into spectacle, overshadowing the ecological and historical ties within the architecture's legacy. From Venice to Milan, I looked for genuine and reparative involvement of Eritrean, Ethiopian, Somali, Libyan, Albanian, and other communities whose bodies and lands were exploited to forge Italy’s so-called “impero moderno.” Discourses advanced, yet exceptionalism merely shifted, as I saw ‘names’ performing reflection for an international stage. “Why are truly low-carbon, locally rooted practices—and the ethical inclusion of those whose histories are tied to these very structures—still so often absent in Italy?” It is a question that must be written and rewritten, not for lack of answers, but because making it clear demands so much that even the sharpest pencil dulls, worn down by the weight of explanation itself.

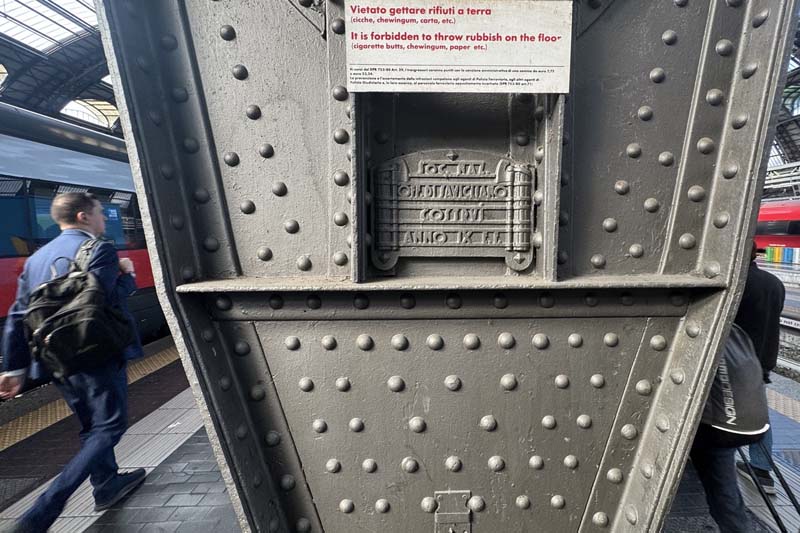

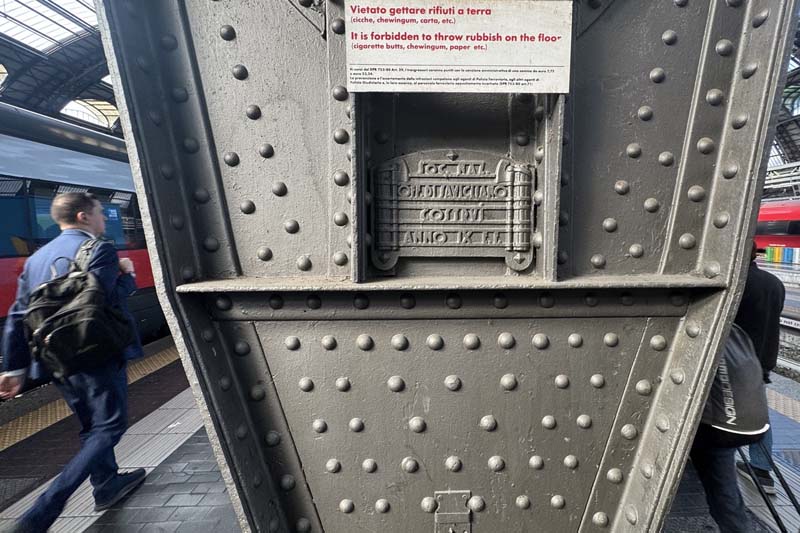

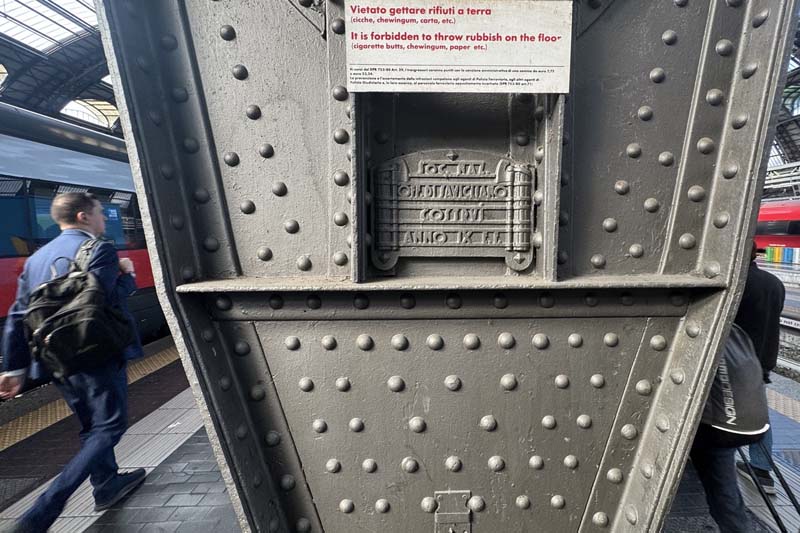

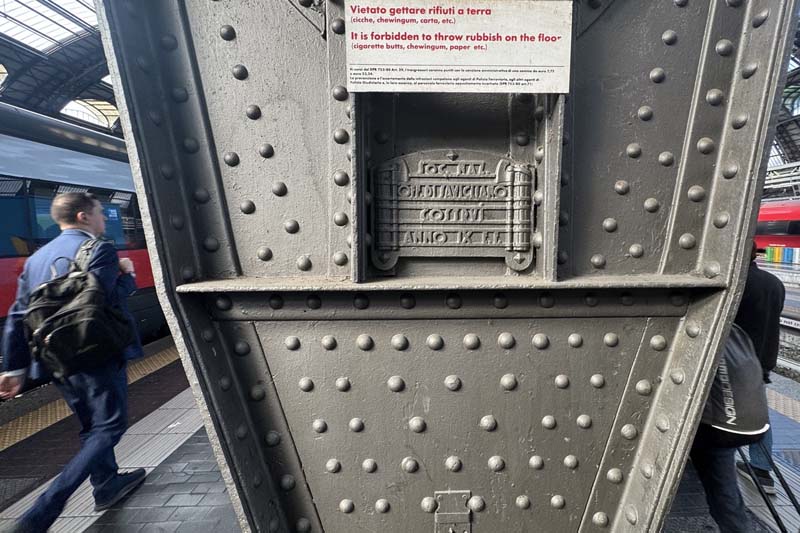

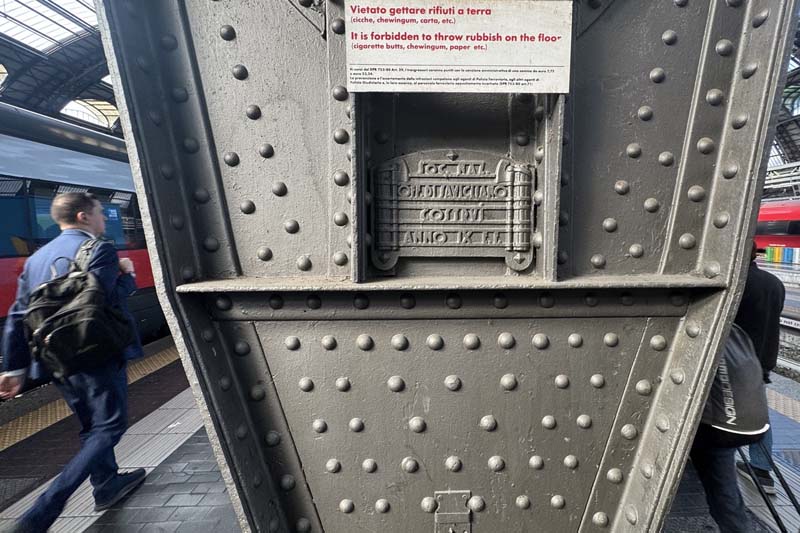

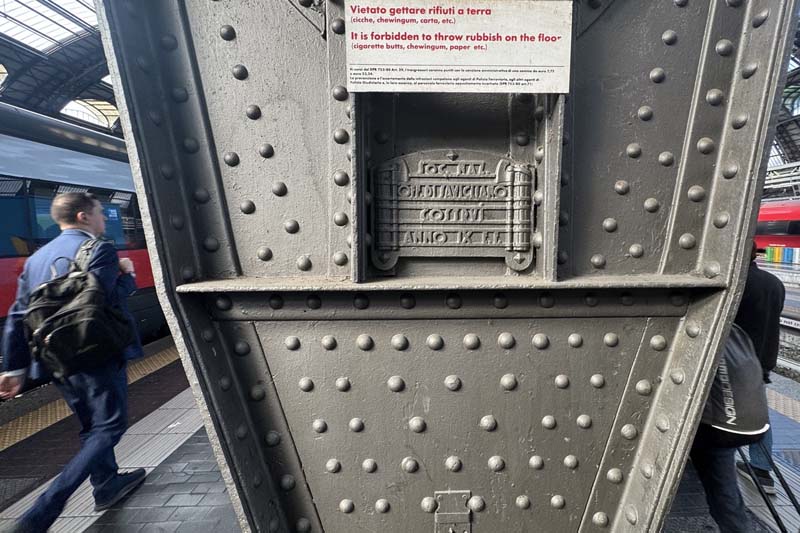

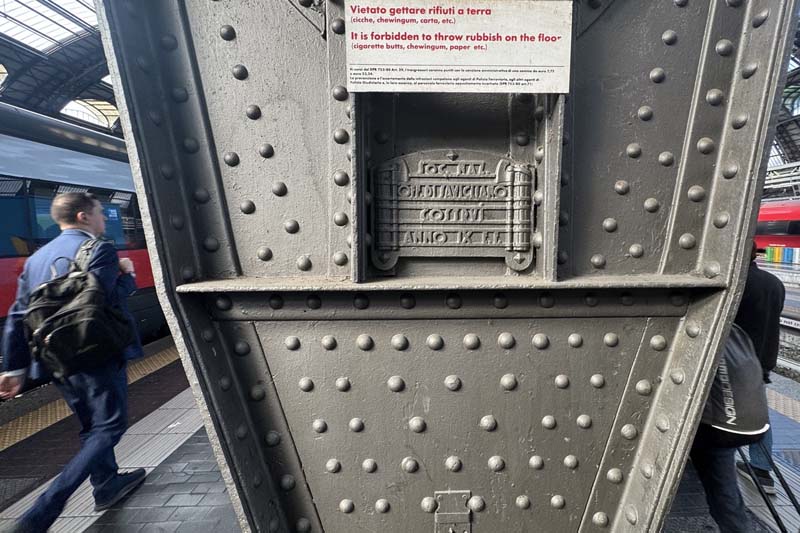

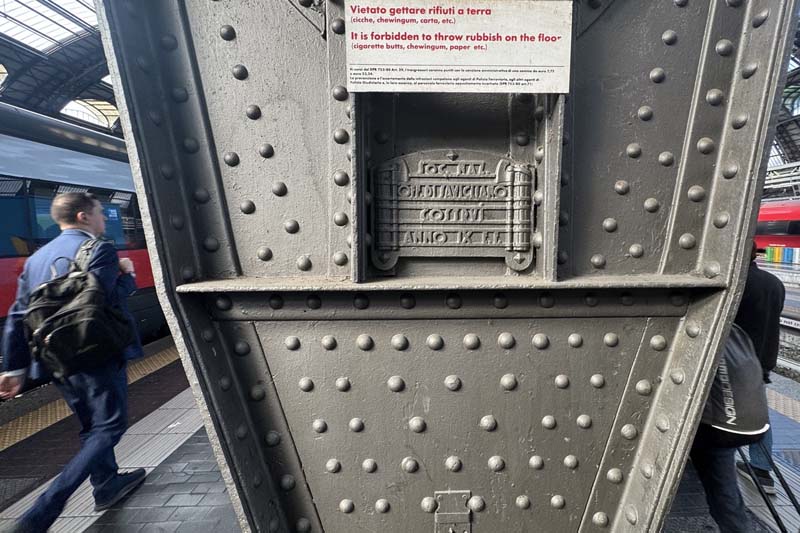

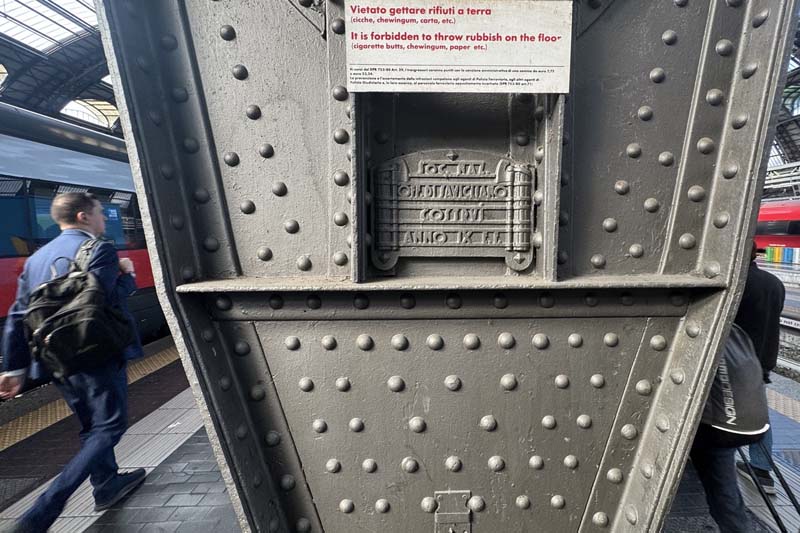

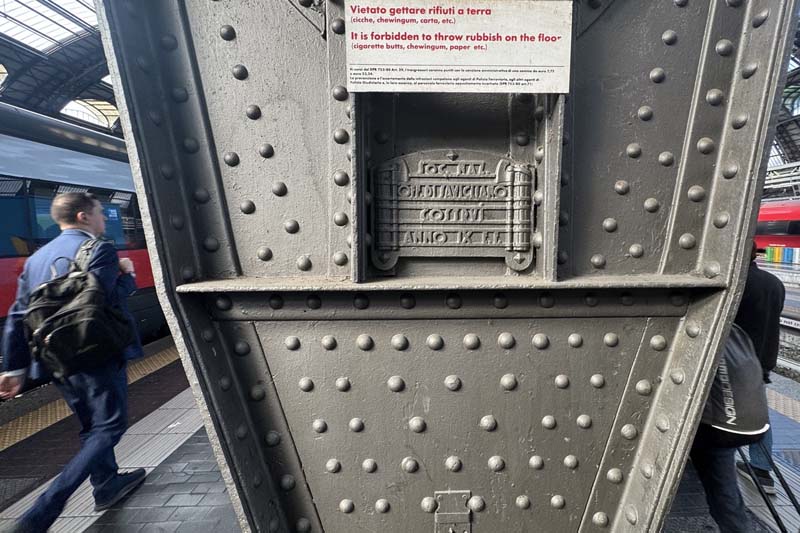

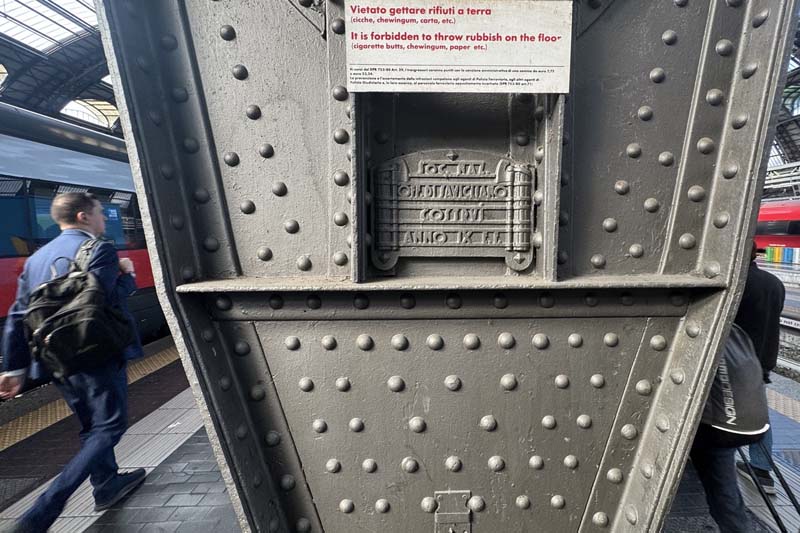

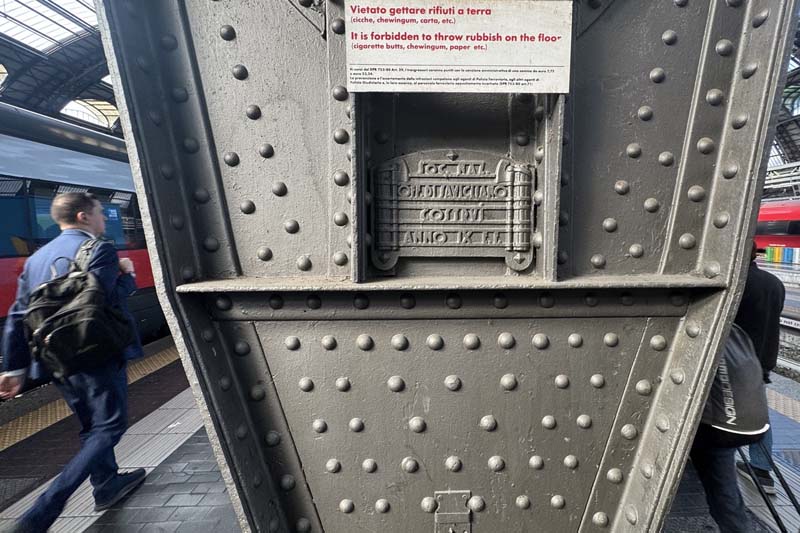

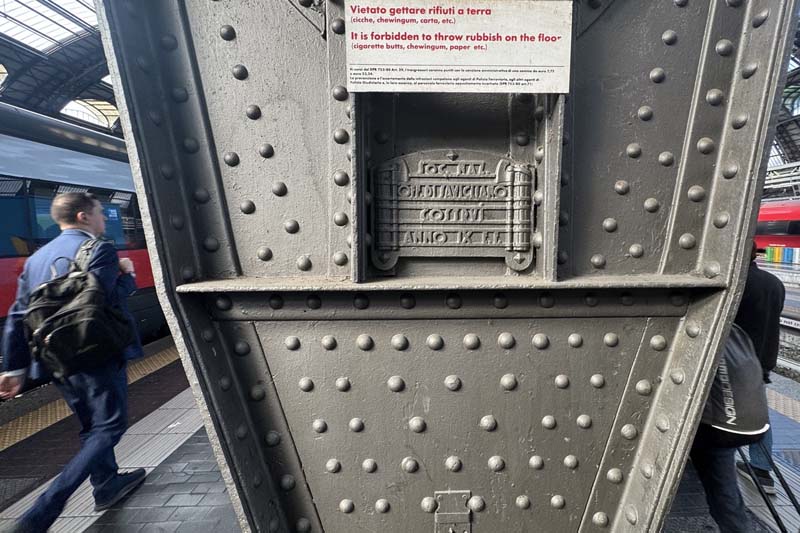

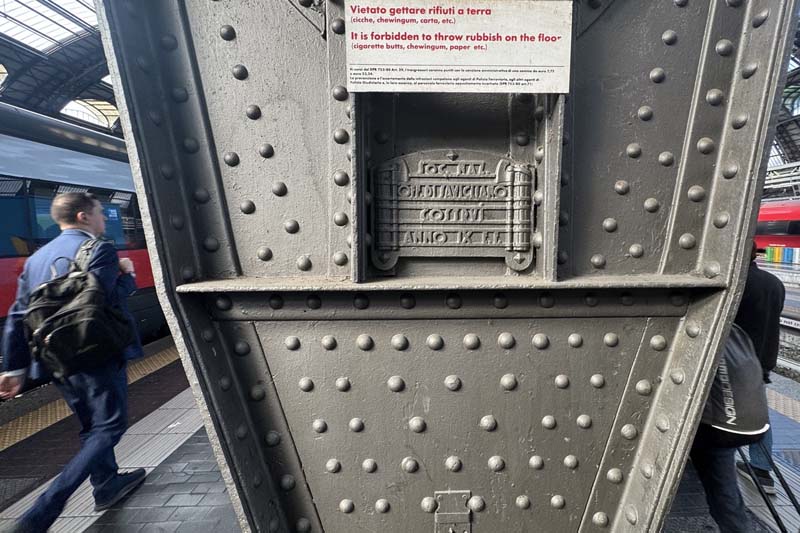

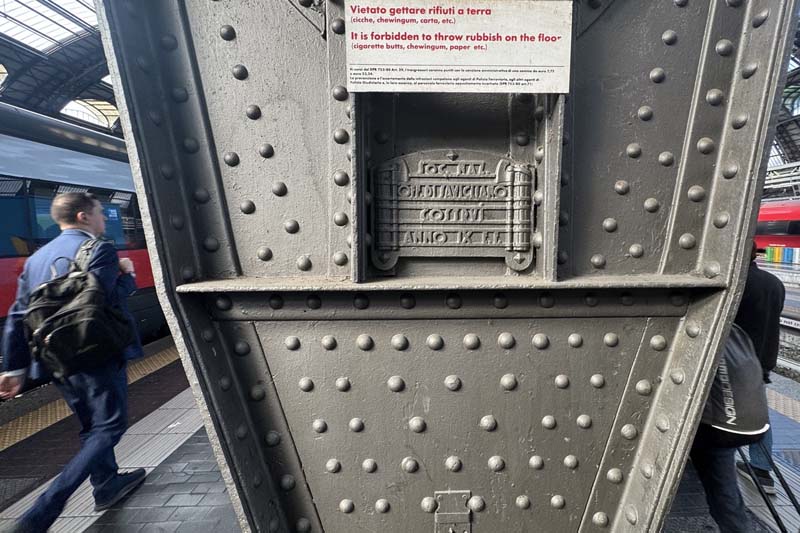

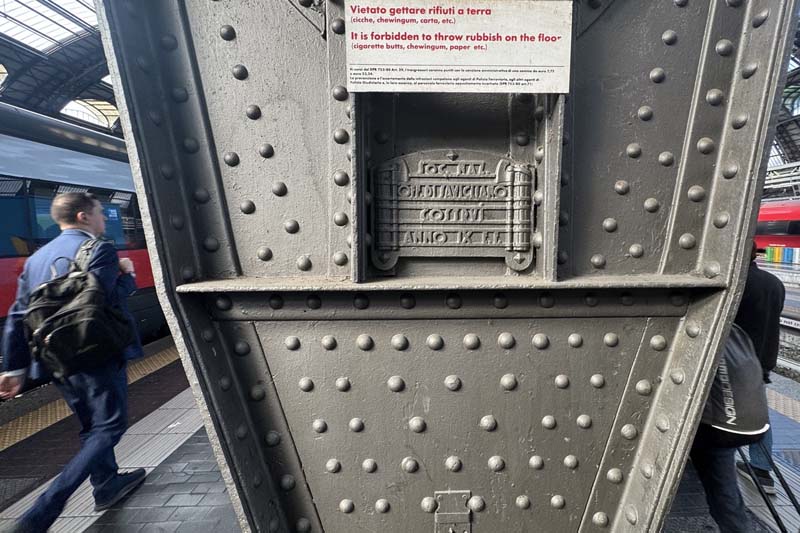

Passing through Milano Centrale in transit to Verona, I began to notice details I had once overlooked. Beneath the station’s vaulted ceiling, the Capitoline wolf appeared perfectly framed into the waiting hall (Fig. 5). On the platform, steel columns bore fasces with the inscription “CONSTRVI ANNO IX F.F.,” or “built in the ninth year of the Fascist Era,” i.e., 1931 (Fig. 6). These symbols, embedded into the station’s very fabric, reveals how fascism inscribed itself onto infrastructure, transforming transit into a quiet extension of state power.

Fig. 5 – Capitoline wolf seen in the waiting hall from platforms, Stazione Milano Centrale, Italy

Fig. 6 – Detail of steel column on the train platform, Stazione Milano Centrale, Italy

Fig. 7 – Section of commemorative wall ‘Binario 21,’ eastern side of Stazione Milano Centrale, Italy

Even today, amidst the rush of arrivals and departures, the eastern walls of ‘Binario 21’ retain juxtaposing traces: one plaque acknowledges the station’s role, Fascist-Italy’s complicity, as a transit point for Nazi-Germany’s Holocaust, while another, just to the left of the art-deco’d “gladius” sword—commemorates railway workers who served from “1940–1945” in the Italian–Ethiopian “war” (Fig. 7). But an Italo-Ethiopian, who may be commuting to Genova, passing by this wall might ask: “What of the years 1935–36? Did they forget chemical gas was weaponized in our mountains, against our peoples, like in the Cave of Zeret?” Stones and inscriptions, even when placed side by side, expose not only the ongoing colonial absences but also the Eurocentric ambiguities that persist in public space regarding national history “d’oltremare” or “overseas.”

In April, reminders of the Partigiani’s (partisan) “resistance” and “liberation” from Benito Mussolini’s fascist state, the Partito Nazionale Fascista (PNF), were unavoidable. While in Verona, intending to visit Carlo Scarpa’s Museo Castelvecchio, I encountered an exhibition about the 80th anniversary of the “Liberation from Nazi-Fascism (1943–1945).” The first exhibit space was a dark room screening 1938 film clips projected beside a white bust of Mussolini. The space carried a haunting stillness. Yet what unsettled me most was not this atmosphere—so familiar from archival encounters—but the curatorial decision to include works by Italian Futurist Renato di Bosso (Renato Righetti), despite his career being steeped in aeronautical and military-oriented productions.

Fig. 8 – Renato di Bosso aeropaintings featured in exhibit at Museo Castelvecchio, Verona, Italy

Fig. 9 – Italian futurist aeropainting depicting Italian colonial village in Libya, “Renato Di Bosso (Renato Righetti), In volo sul villaggio coloniale "M. Bianchi", 1938, oil on masonite, cm 89,5 x 100, Wolfsoniana – Palazzo Ducale Fondazione per la Cultura, Genova, 87.1070.5.1” (Source: courtesy of the Wolfsoniana Foundation, 2025)

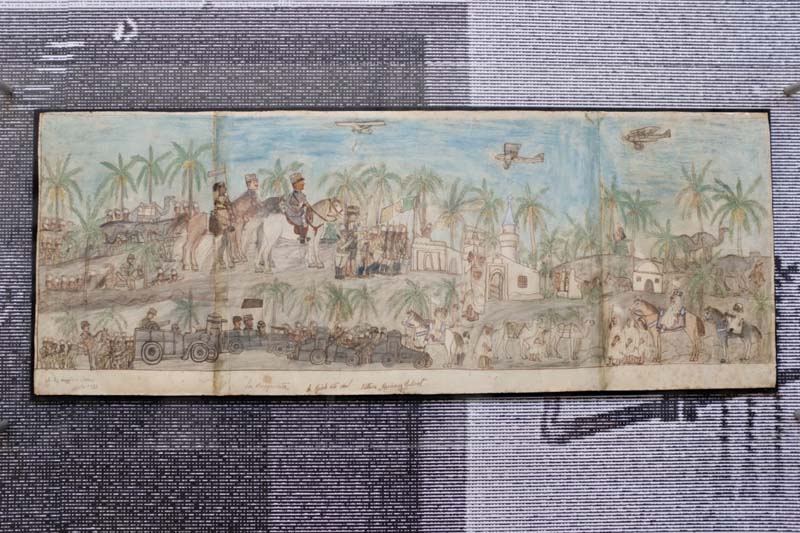

The three “aeropaintings” on display in the main exhibit space (Fig. 8) reflected the dynamism of second-generation Italian Futurists. I immediately recognized Di Bosso’s work, already familiar with his “In volo sul villaggio coloniale ‘M. Bianchi’” (“Flying over the colonial village ‘M. Bianchi’”), recently exhibited at the Wolfsoniana Foundation in Liguria (Fig. 9). Though the painting does not explicitly name Libya or North Africa, the double-exposure of the built subject closely resembled one of the many standardized agricultural settlements constructed in Italy’s occupied territories. The painting, without a doubt, depicts the Tripolitanian rural center in Libya called ‘Villaggio Bianchi,’ designed by Umberto di Segni and named after Michele Bianchi, a founding member of the Fascist Party.

It is no coincidence that the painting was produced in 1938, the same year 20,000 Italians—known as the Ventimila—“immigrated” to standardized settlements along Libya’s coastline. This state-settlement program, under the Ente per la Colonizzazione della Libia with the INFPS, was certainly overseen by aviator-turned-governor Italo Balbo (famous for his transatlantic flight to Chicago, noted in my first SAH report). To de-mystify sanitized memories of Nazi–Fascist entanglements—generically remembered in April—it is worth recalling that Balbo hosted Nazi-German officials in Libya during the 1930s, some of whom were tried at Nuremberg. Some scholars suggest Nazi officials observed Fascist Italy’s racial and colonial policies of “ethnic reconstruction” and “demographic colonization.” However, it may have been all but normal, highly planned state-sponsored visits that involve nothing but incredulously staged parades, many of which remain archived by Luce. Nostalgic formalism—the whitewashed rural centers and farmhouses still described as “modern” or even “metaphysical”—ultimately fetishizes what were, at their core, standardized design packages built to serve Fascist Italy’s agenda overseas.

Fig. 10 – Ex-cinema Astra facade, Verona, Italy

Fig. 11 – ‘Via Adua’ street elevation, Verona, Italy

Fig. 12 – ‘Via Bengasi’ intersection, Verona, Italy

Fig. 13 – ‘Farmacia dell Cirenaica,’ Cyrenaica neighborhood in Bologna, Italy

Passing a former Cinema Astra (Fig. 10), I reflected on the persistence of rationalism across cities. At times, it signaled civic prominence; at others, decay. Yet it almost always reverberated the ideological legacies of fascism, where colonized places from Italy’s overseas campaigns resurfaced, their language reshaped to fit Italian speech in the streets. The phonetic flattening of ‘Via Adua’ (Fig. 11) shown in the work of Italo-Ethiopian Eritrean artist Jermay Michael Gabriel, ‘Via Adwa’ (2023), confronts this translation directly, crossing out the ‘u’ on the Carrara marble and marking the missing ‘w’ in black ink to restore its name.

I not only walked past ‘Via Adua’ in Verona, but cycled past the central station and through an industrial zone where I came upon ‘Via Bengasi’ (Fig.12). The setting felt remote, despite residences in the vicinity, and was disconnected from the city center, characterized by neglected buildings, patched walls, and overgrown vegetation. It reminded me of the enclave I had walked through in Turin. The second street sign, engraved in stone and mounted on a fence, was sub-labeled ‘Città d’Africa.’ These names—once markers of imperial claim—remain etched.

Unlike Verona and many cities where colonial-era street names remain intact, Bologna has uniquely addressed its colonial “inheritance,” acknowledged by collectives like Resistenza in Cirenaica. In the neighborhood of ‘Cirenaica,’ streets once named after Libyan cities—Tripoli, Derna, Bengasi, Homs, Zuara, Cirene—were renamed. They now have dual signs, pairing colonial names with Italian partisans’ names who resisted ‘Nazi-Fascism.’ For example, ‘Via Derna’ is now ‘Via Santa Vincenza: Caduto per la liberazione’ (Fallen for the Liberation). ‘Via Libia’ is the only sign unchanged and has remained since the 1920s, when workers settled in an enclave of the ‘old’ historic city center. Colonial names still surfaced in local businesses, including ‘Farmacia della Cirenaica’ (Fig. 13) and the ‘Mercato Cirenaica.’

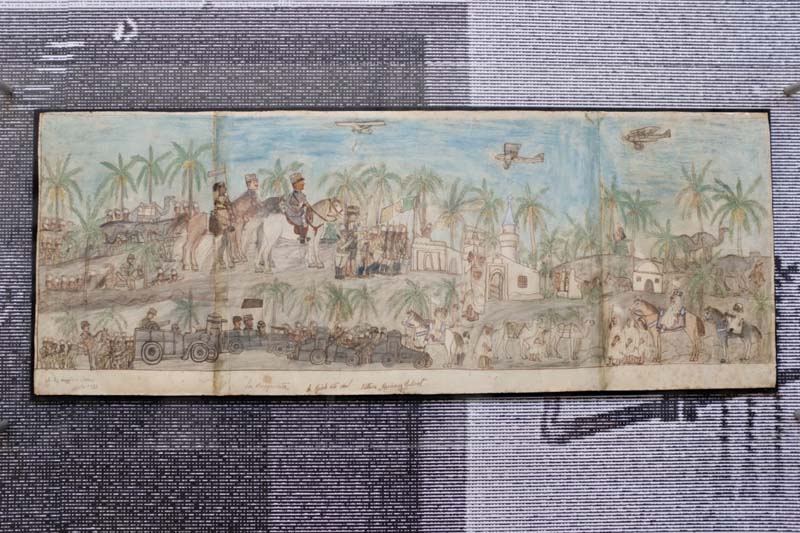

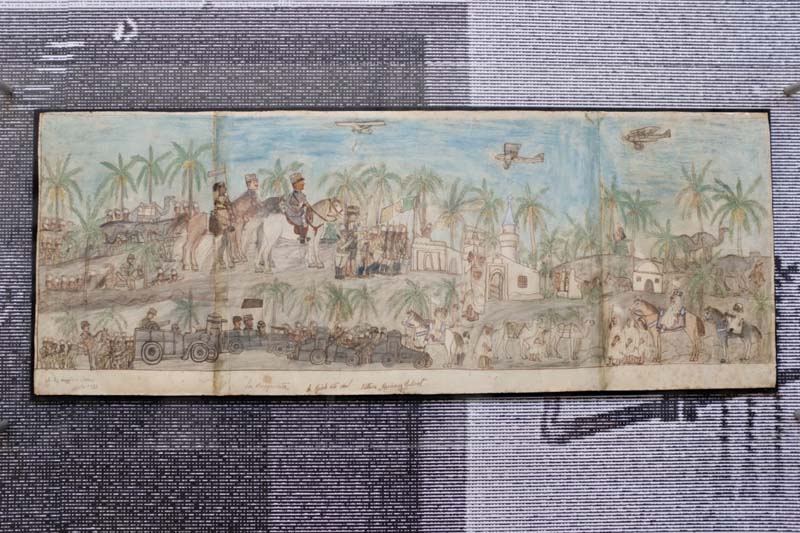

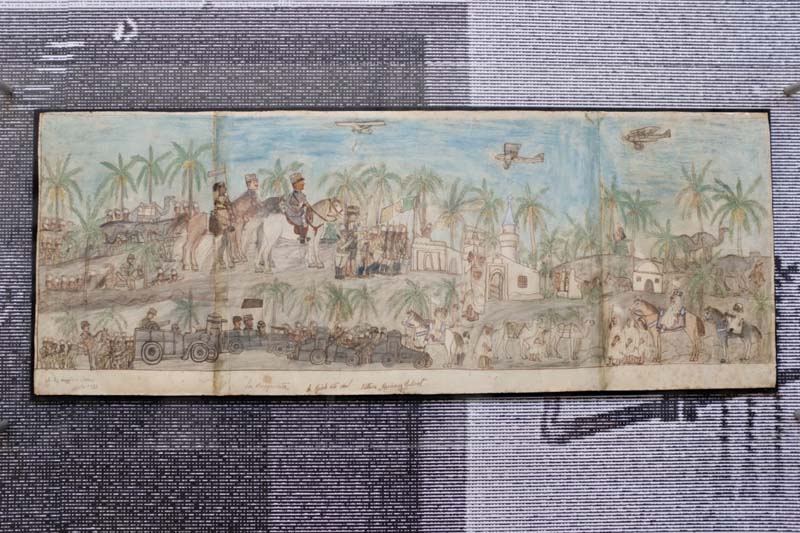

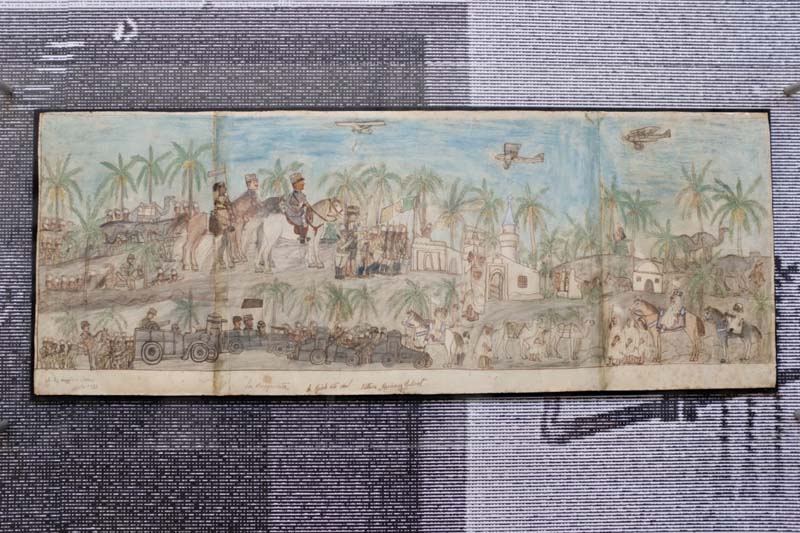

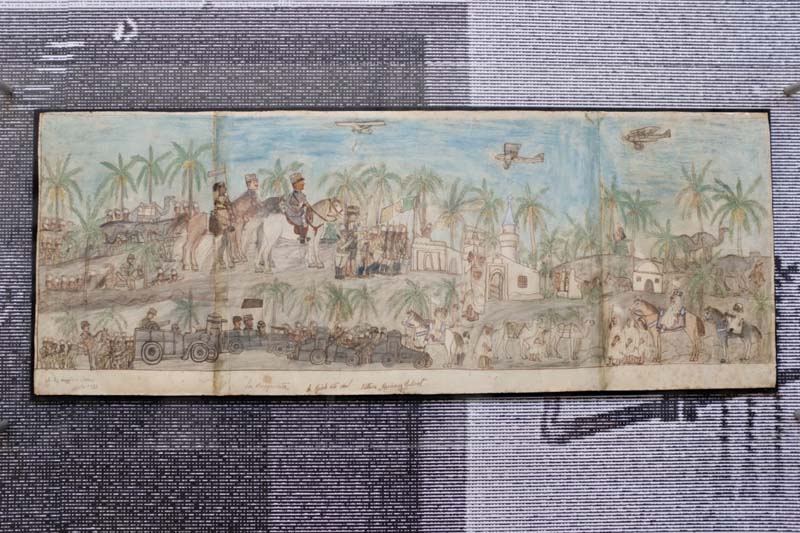

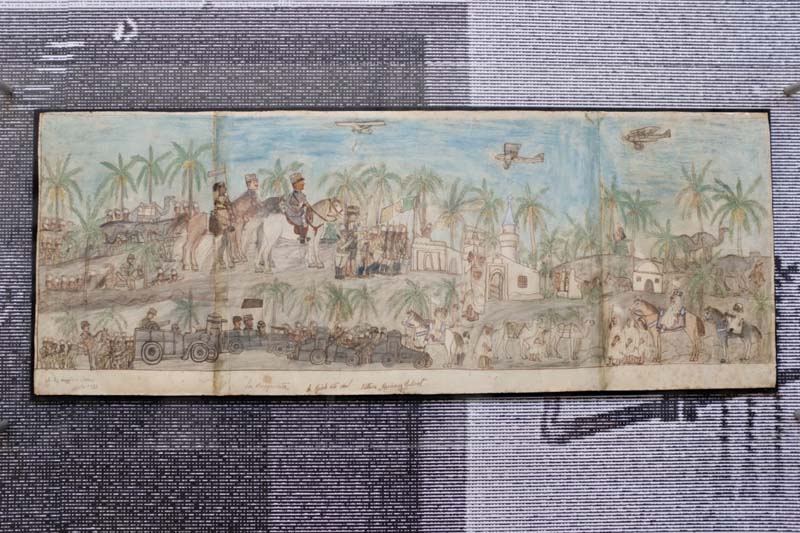

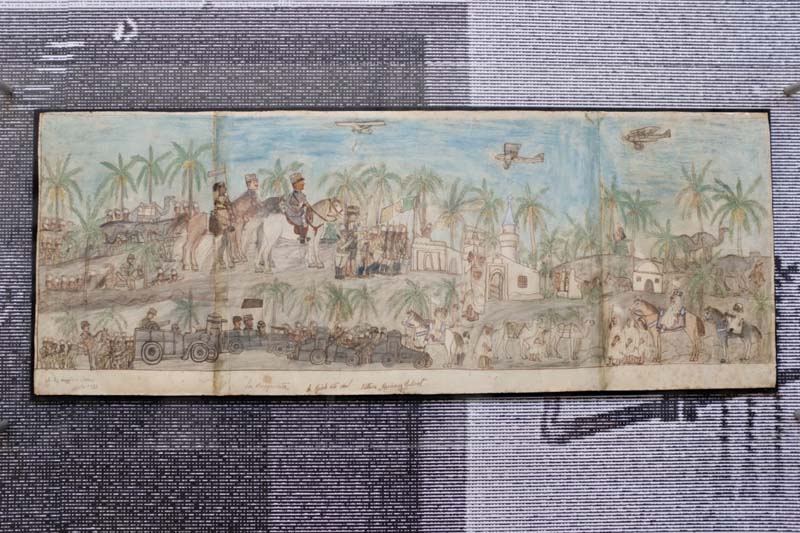

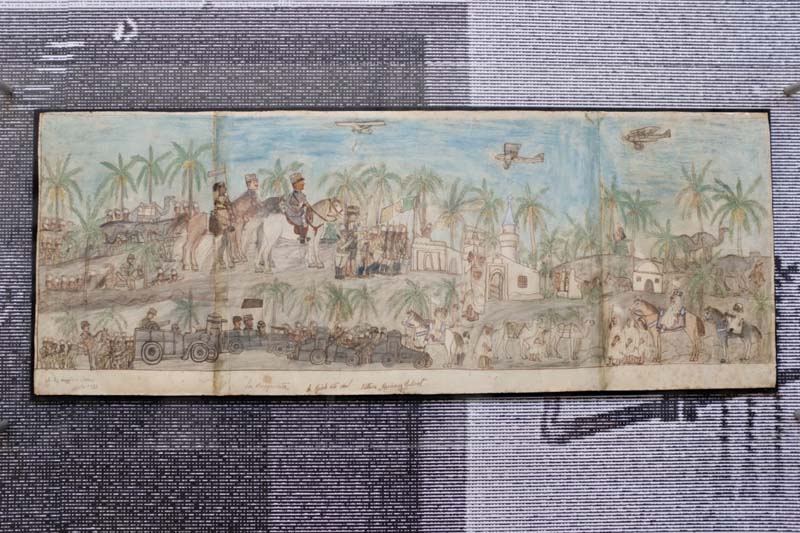

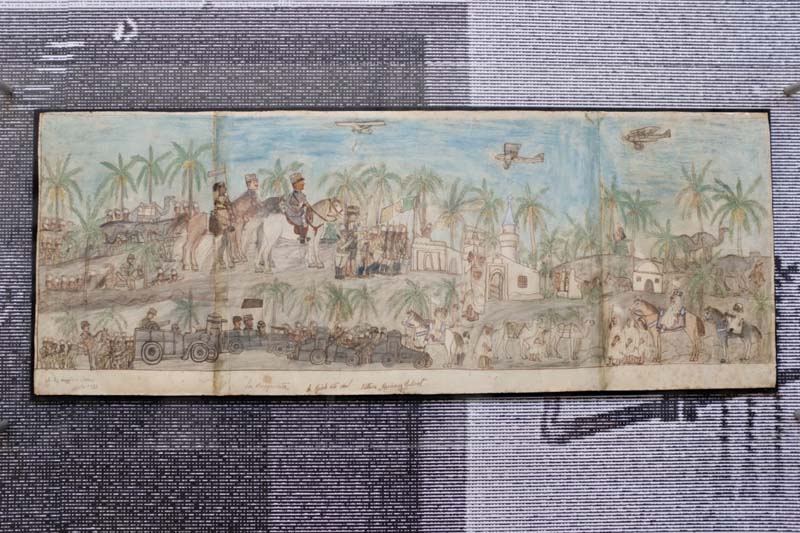

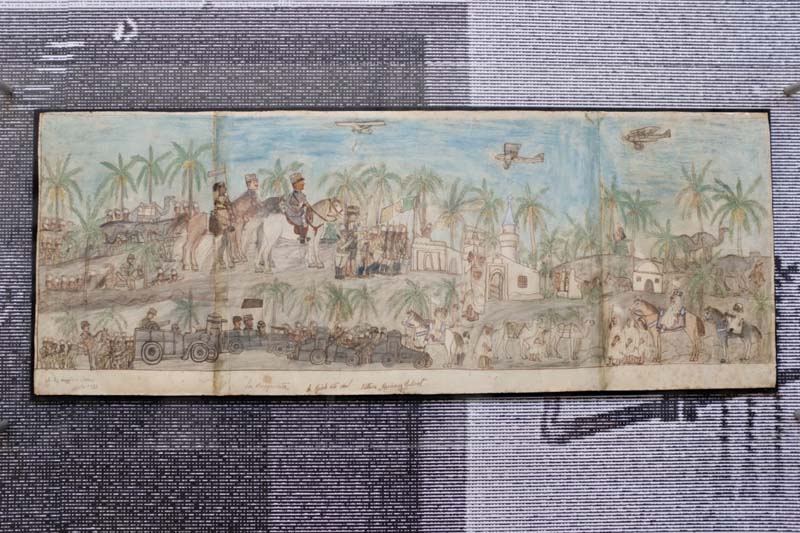

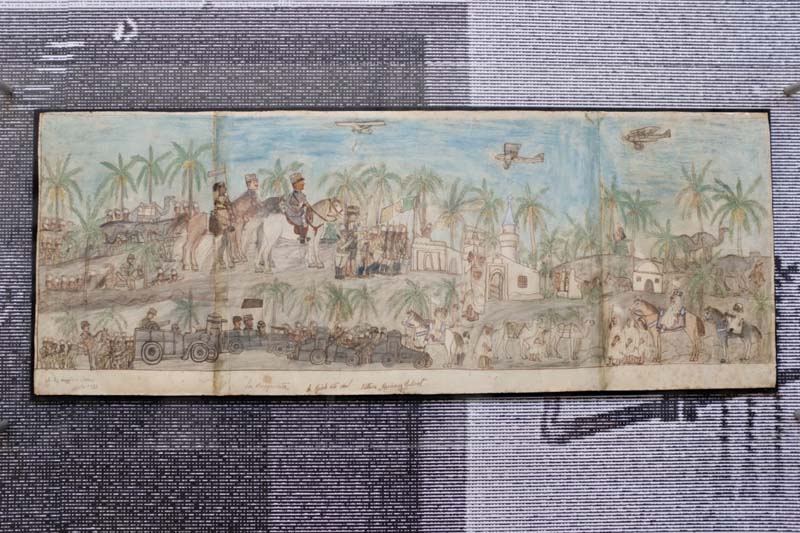

Fig. 14 – Drawing by conscripted Eritrean Ascaro in Libya, Gariesus Gabriet’s “Conquest of the Oasis of Gialo, 1920-30s,” April 1928, Museo della Civiltà, Rome, Italy

Fig. 15 – ‘Libia’ Metro, Rome, Italy

Fig. 16 – Street signage of clustered former colonial territories, Rome, Italy

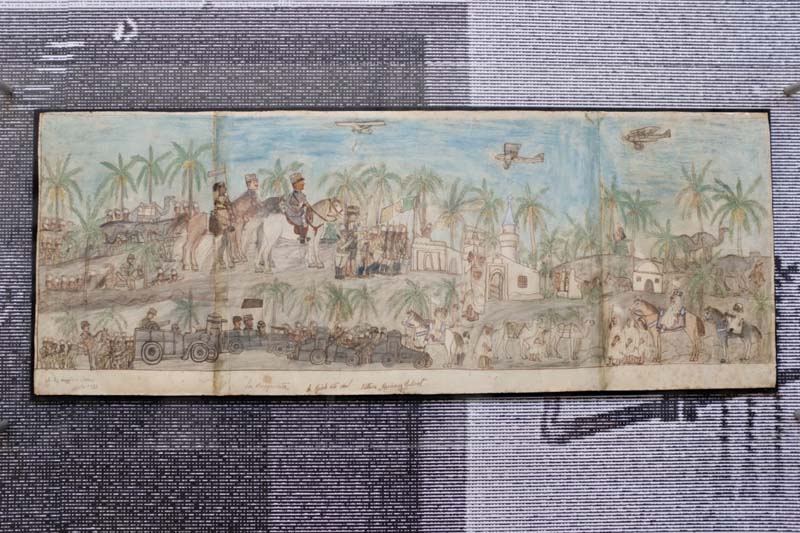

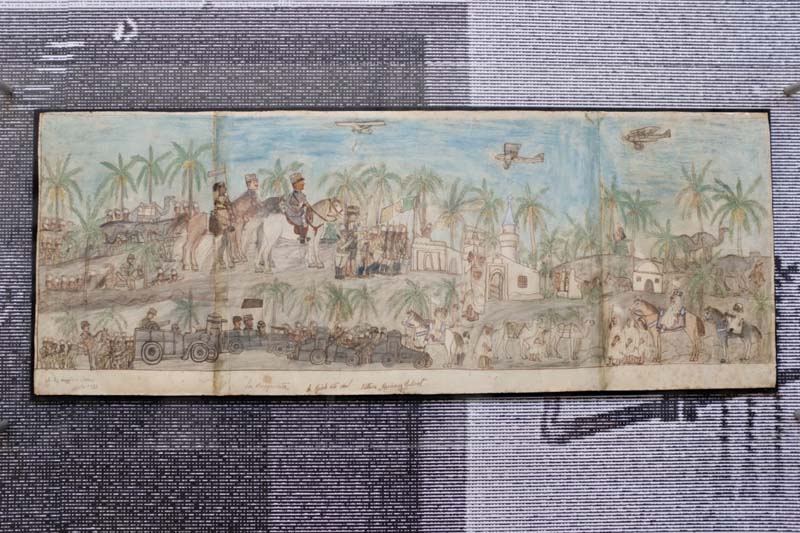

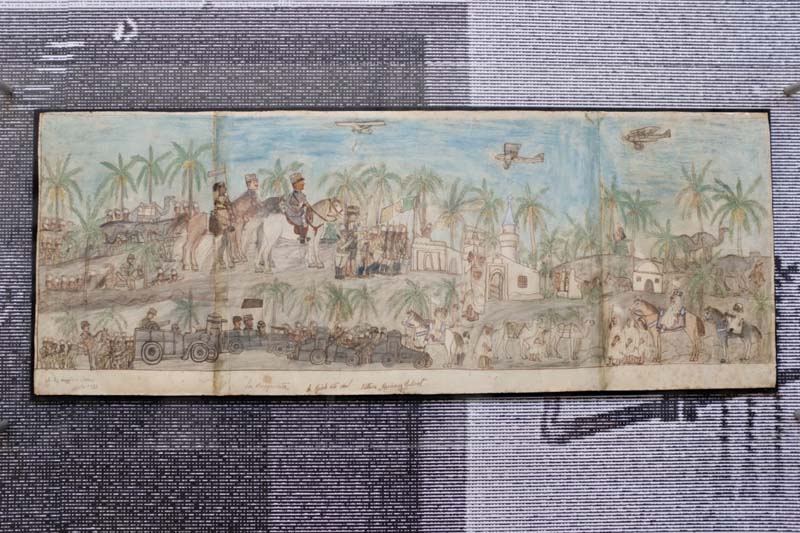

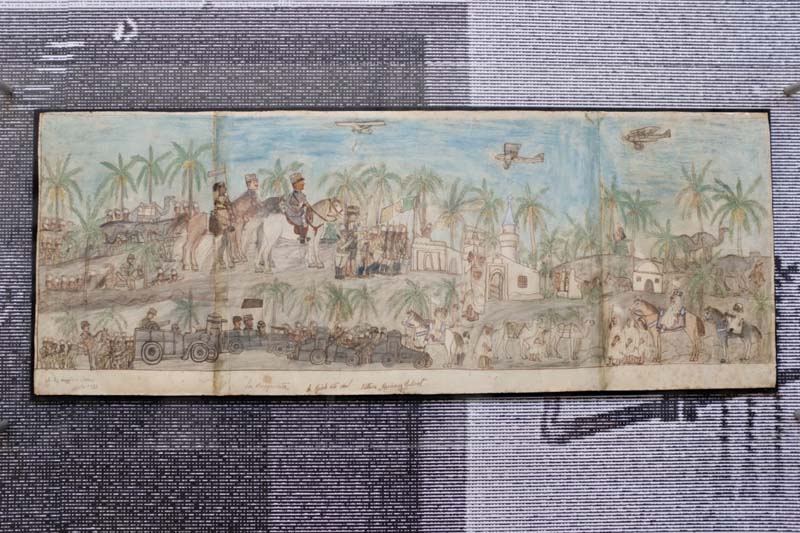

In Rome, I encountered objects in the former ‘Museo Coloniale,’ now the ‘Museo della Civiltà.’ Among the displayed upon my visit, a 1928 drawing by an Eritrean ascaro Gariesus Gabriet, “Conquest of the Oasis of Gialo,” stood out (Fig. 14). Riding the metro from the stone utopia of EUR to the 'Stazione Libia' neighborhood (Fig. 15), the drawing from the museum remained in mind as I walked along the streets scripted with “African” names—Viale Etiopia, Piazza Gondar, Via Libia, Via Eritrea (Fig. 16). The origin of Gabriet’s illustration is unclear—perhaps it was commissioned or solely to be collected and catalogued for the museum—but its display underscores how imperial gaze acted beyond conscription. Walking through housing blocks from the 1920s and ‘30s, threaded with familiar names, reveals how the rhythms of life soften the colonial weight inherited by the neighborhood.

Fig. 17 – Printed photograph of the typical lungomare balustrade, Darsena Toscana, Livorno, Italy

Fig. 18 – Fontana dei Mostri Marini by Pietro Tacca, Piazza Colonnella, Livorno, Italy

Fig. 19 – Monument of Ferdinand I de’ Medici, ‘Quattro Mori’ by Pietro Tacca, Piazza Michele, Livorno, Italy

Fascist-era constructions overlay earlier buildings of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany in Livorno. I was drawn in by the rational forms rising across the street from walking along the Darsena Toscana (Fig. 17). Along Via Grande towards the sea, market stands filled the openings to the covered walkways, demonstrating how rational facades became seamlessly integrated and juxtaposed. A replica of Pietro Tacca’s ‘Fontana dei Mostri Marini,’ the original of which is located in Florence (Fig. 18), is situated near another work by Tacca at Piazzale Micheli. Tacca’s ‘Four Moors’ (Fig. 19) was installed on a monument dedicated to Ferdinando I de’ Medici in the seventeenth century. A man, carved from Carrara marble, stands tall over four men in bronze, crouched and chained at the corners of a rectangular pedestal. A sign near the ‘4 Moor’ café describes the “moors” as “pirates mainly from the North African provinces of the Ottoman Empire.” The monument’s material contrasts and its composition of elevation and restraint render the disparity it represents unmistakable: a visual language of subjugation, incarceration, and hierarchies of race. I watched families and tourists pause to take photographs with the monument in the background, their casual gestures softening the edges of the scene behind them. To describe oneself as Italo-Arab or Italo-African—“African” long steeped in ongoing racial stereotypes—means, inescapably, feeling the weight this monument still pressing into the present, even as others dismiss it with a casual, ‘Ma questa è la storia della città?’

Fig. 20 – Museo Civico Giovanni Fattori, Livorno, Italy

Fig. 21 – Photograph found in Mercantino depicting ‘Fontana della Gazella’ in Tripoli (Libya), Piazza Luigi Orlando, Livorno, Italy

I mainly visited Livorno to see the original model of the ‘Fontana della Gazzella’ (c. 1934) by Livornese sculptor Angiolo Vannetti, which became the reference to what stood along the ‘lungomare’ in Tripoli, Libya. Vannetti’s working model is preserved at the 19th-century Villa Mimbelli in Museo Civico Giovanni Fattori (Fig. 20). Unfortunately, building renovations prevented me from seeing it in person. The statue in Libya, installed during the colonial era, stood until it was destroyed by religious extremists in 2014. Throughout the year, memories of that era, especially the sculpture, resurface in Facebook groups dedicated to Italy’s past—spaces where Italians and Libyans, many now over sixty, share stories, recipes, and greetings beyond the “difficult” parts of history. For a moment, Italians and Libyans were neighbors, as I heard a Libyan recall their neighbor giving their humble family a ‘panettone’ around Christmas time many many years ago. The sculpture continues to be reimagined by Libyan artists in countless works, most recently by Born in Exile, since its disappearance.

Not far from the museum, at the street market in Piazza Luigi Orlando, I sifted through boxes of antique postcards. By chance, I came across an image of the very sculpture that had brought me to Livorno—the ‘Fontana della Gazella’ in Tripoli (Fig. 21). This moment echoed the persistence of colonial fragments or remnants of “wars” overseas, which are now traded casually as collectibles across flea markets.

Fig. 22 –Reenactment preparations of ‘Difesa di Livorno’ in Piazza della Repubblica, Livorno, Italy

Fig. 23 – Building corner, Via Giosue Carducci & Via Vittorio Alfieri, Livorno, Italy

Crossing Piazza della Repubblica, men in camouflage pants were preparing a stage as chairs were being unloaded from a truck into the plaza, just in front of a rationalist palazzo (Fig. 22). Under the colonnade of a neoclassical palazzo, across the plaza, members of a historical reenactment group in Risorgimento-era costume gathered in front of the storefront ‘Comunità Senegalese Livorno e Provincia.’ Later, I learned the performance marked the 175th anniversary of the “Difesa di Livorno,” restaging the city’s “resistance” during the Risorgimento. It was not only palaces but residences, rounded buildings, demarking street corners, that became a visual signature I would recognize later in other cities built during the 1920s and 1930s (Fig. 23). In passing to depart Livorno, steps away from the train station, more familiar streets: ‘Via Bengasi’ and ‘Via Tripoli.’

The National Central Library of Florence (BNCF) holds a prominent position along the Arno. The negative space of Piazza dei Cavalleggeri opens toward the eastern edge of the city, allowing traffic to flow in. Hidden behind the plot along the riverfront is ‘Via Tripoli’ (Fig. 24). The plaque marks the street, which runs parallel to the Arno and leads toward the library’s piazza. According to scholars at the European University Institute’s ‘Post-colonial Italy: Mapping Colonial Heritage’ project, “the Florentine city government under the mayor Filippo Corsini decided to rename the street into Via Tripoli to commemorate a successful conquest” during Italy’s “war” with the Ottomans.

Fig. 24 – Via Tripoli feeding into the front plaza of Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, Florence, Italy

Fig. 25 –Detail of ‘The Divine Comedy’ and Fascio symbol depicted on bronze crest, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, Florence, Italy

Fig. 26 – View of Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze façade across the Arno, Florence, Italy

Continuing from Via Tripoli across the library’s façade, one encounters bronze-adorned crests affixed to the building. One inscribes “Divina Commedia,” a renowned Italian text by Dante Alighieri, near it, another crest bearing a bundle-axe fascio (Fig. 25). The PNF transformed Dante into a national icon, particularly in Florence, despite his exile from the city in the 14th century. I was reminded of this paradox months later in my last stop of the fellowship when—through a bookstore window in Casablanca—I saw Dante on the translated copy of Edward Said’s book ‘Reflections on Exile and Other Essays’ (2000) in Arabic. It left me wondering: why did Said choose Dante on the cover for a ‘meditation’ on ‘exile’? And why did a Fascist-era institution celebrate Florence’s ‘wandering humanist’ while unleashing its own ‘inferno’ overseas? The library, positioned prominently along the Arno, becomes a telling example of how institutions assemble narrative into public space (Fig. 26).

I walked across the city to the first archive I visited as a graduate student at the former ‘Istituto Agronomico per l’Oltremare’ (IAO), known today as ‘Agenzia Italiana per la Cooperazione allo Sviluppo, AICS’ (Fig. 27). Looking at the entry past my reflection, I could see green marble stairs rising into the hall I had walked past years earlier. Palm motifs appear on the grilles of the institute’s front doors—echoing those on the light fixture at Bologna’s ‘Farmacia della Cirenaica’—a lingering emblem of exoticization often used to reference lands “d’oltremare” iconographically. Even if I wanted to enter, a sign read “Campanello Guasto” or “broken doorbell” (Fig. 28). These signs of closure reveal what happens when institutions are left suspended due to a lack of investment. Neither erased nor fully engaged, but locked behind closed doors.

Fig. 27 – Roundabout in front of the former Istituto Agronomico per l'Oltremare, Florence, Italy

Fig. 28 – Looking into the “permanently closed” ex-Istituto Agronomico per l'Oltremare, Florence, Italy

After my time in the Dodecanese and Albania, I crossed the Adriatic to Bari. I recall walking along the seafront promenade, passing the fortified city, ‘la città vecchia,’ which reminded me of other Mediterranean ports like Tripoli, where old city walls meet the sea and its ‘modern’ extension, built throughout the early 20th century. Along the ‘lungomare’ extending the city south, rationalism’s footprint outlined the route to the nearest ‘spiaggia libera’ or public beach (Fig. 29/30). The institutional blocs were tied into the neighborhood by streets like Via Libia, Via Durazzo, Via Addis Abeba, and Via Somalia, reflecting the clusters of colonial names I had seen in regions north of Puglia.

Fig. 29/30 – Along the lungomare promenade, Bari, Italy

Fig. 31 – Volkswagen Beetles from Libya seen at the Apulia Volks Club, Bari, Piazza Libertà, Bari, Italy

I passed the Apulia Volks Club Bari gathering in Piazza Libertà (Fig. 31) and saw an institutional building stenciled for the first time, a symbol of broken rationality. Three Libyan-plate Volkswagen Beetles with club stickers from Derna and Tripoli caught my eye. Unlike Algerians in France, Angolans in Portugal, and Ethiopians in Italy, Libyan presence is rare; the country did not receive a large diasporic community after the Italian occupation ended in 1943.

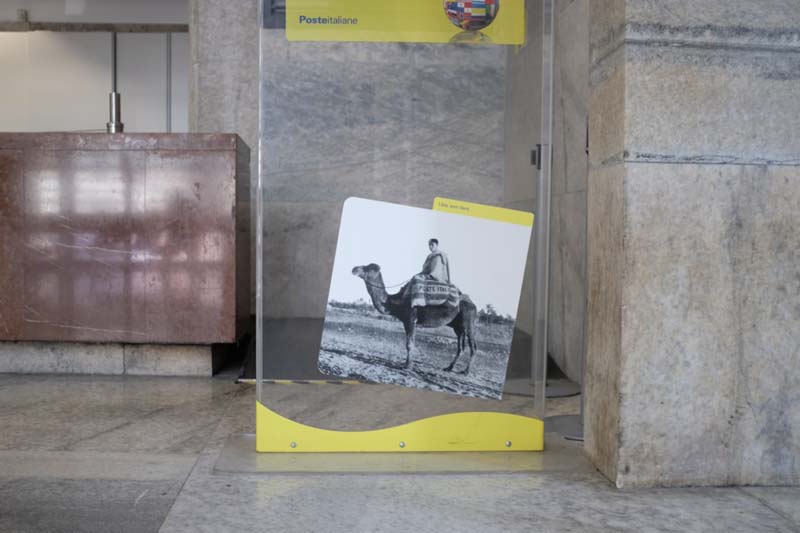

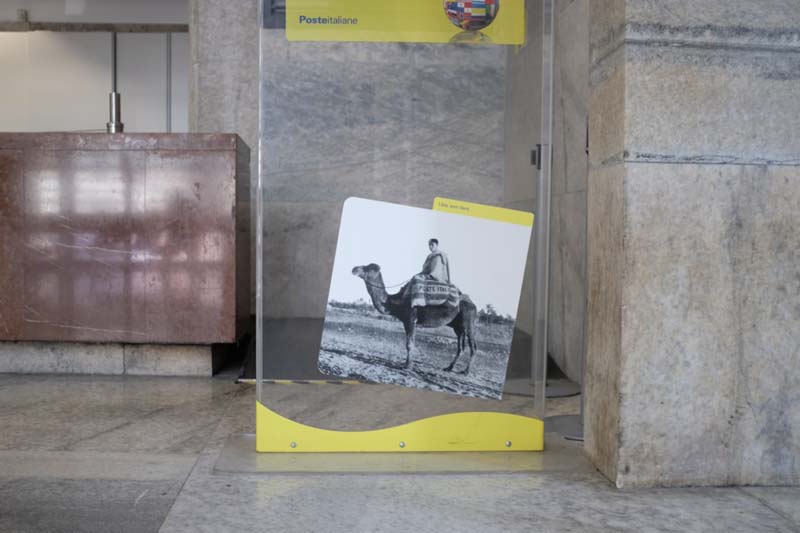

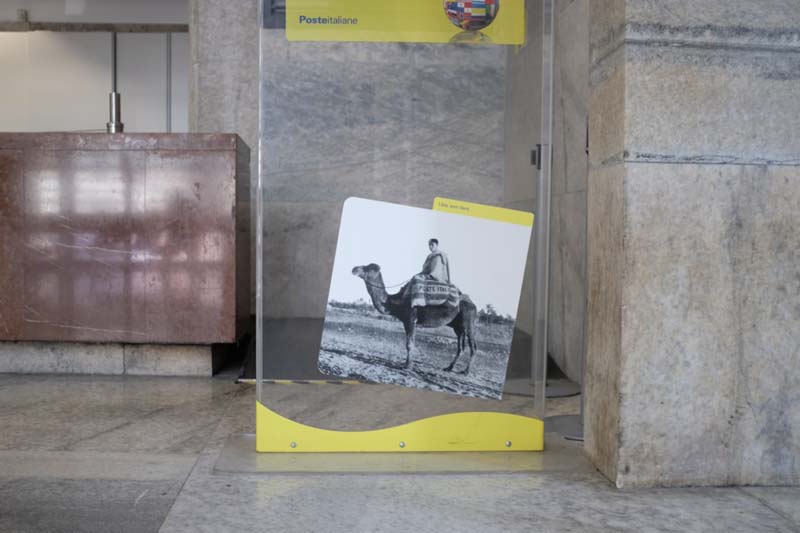

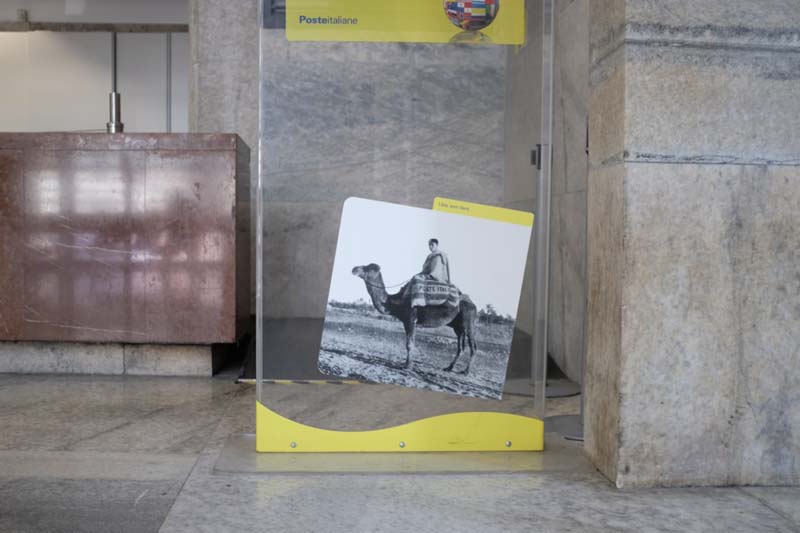

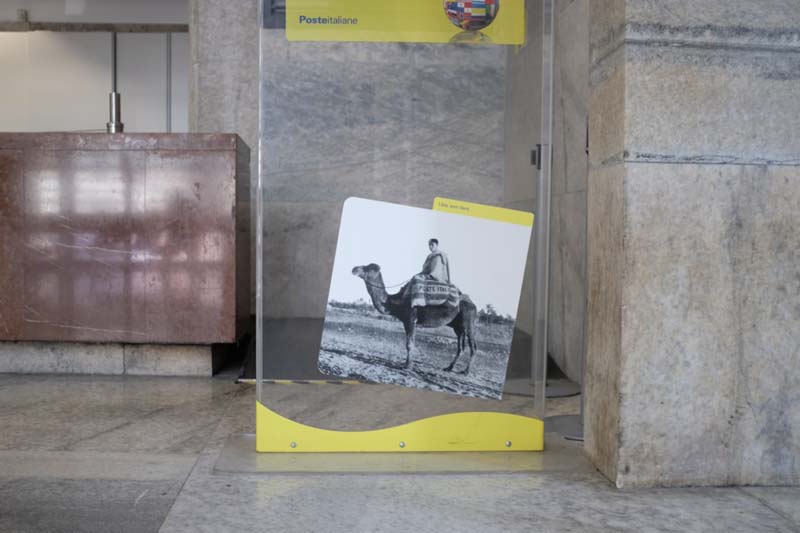

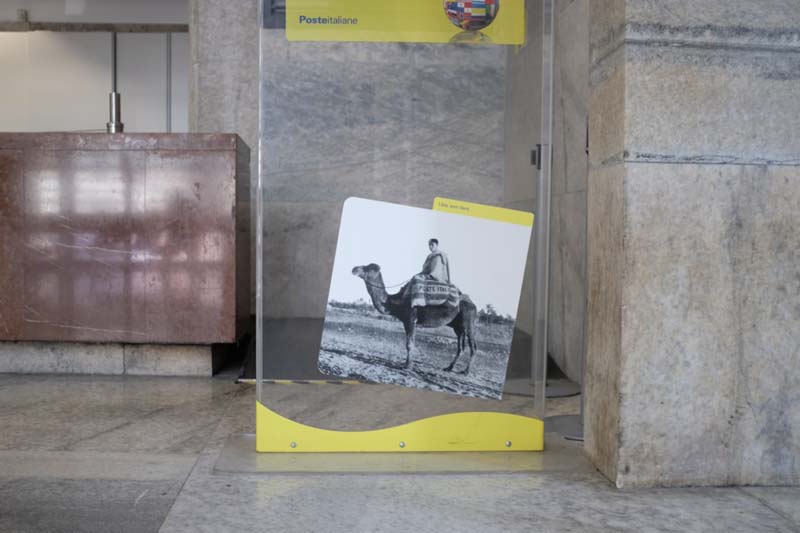

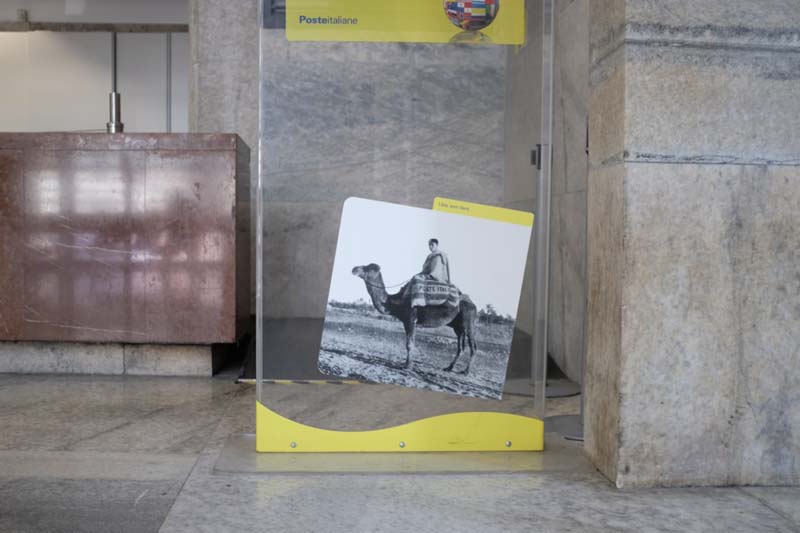

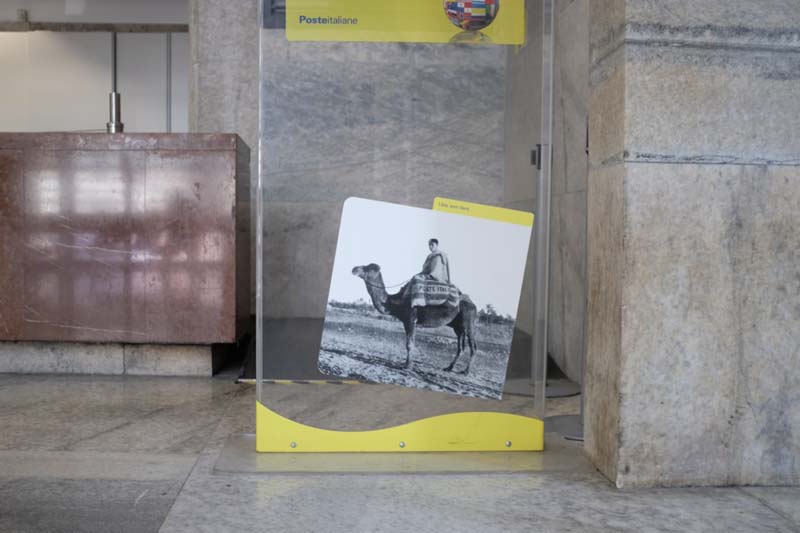

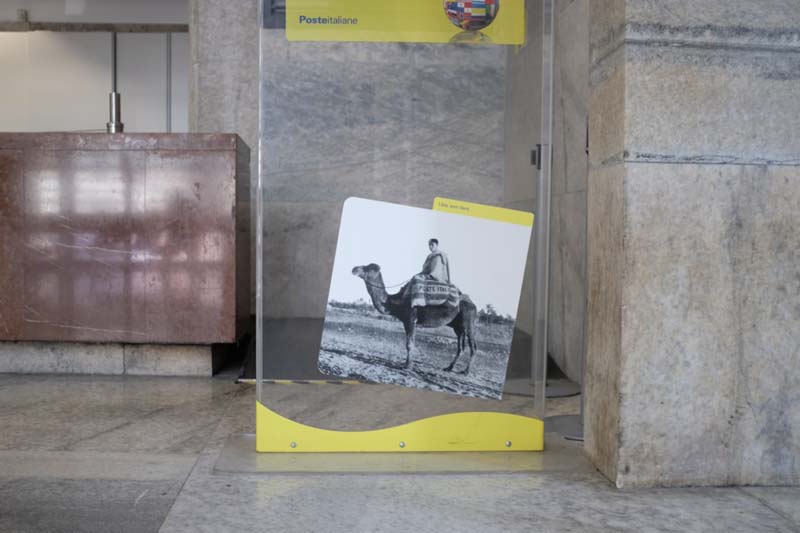

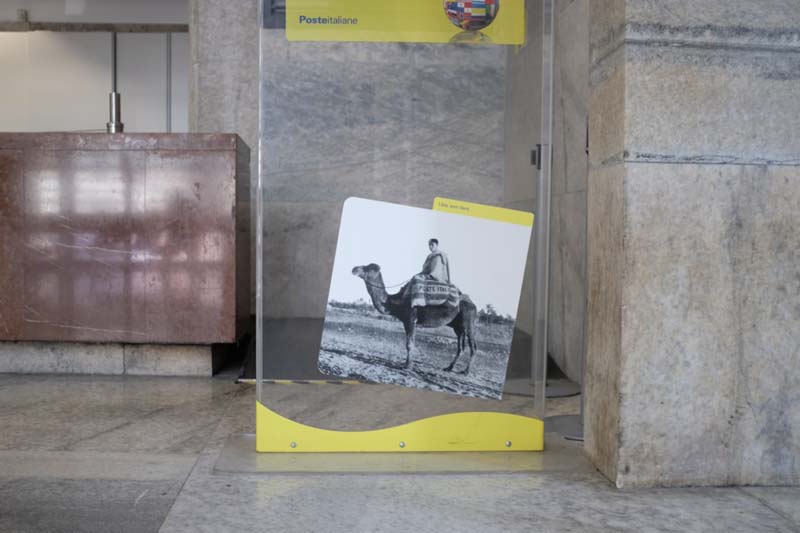

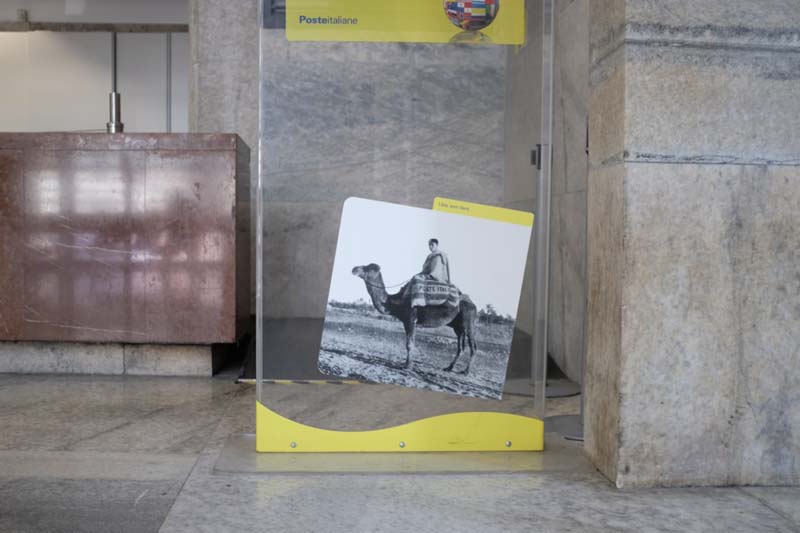

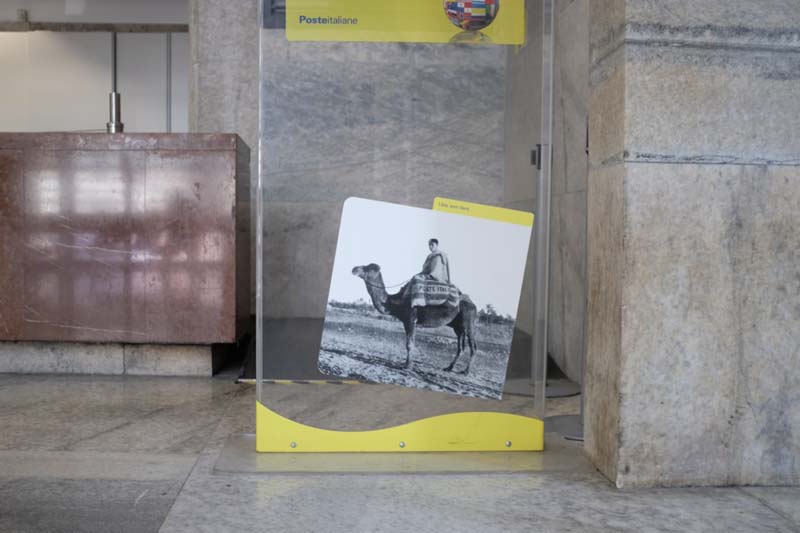

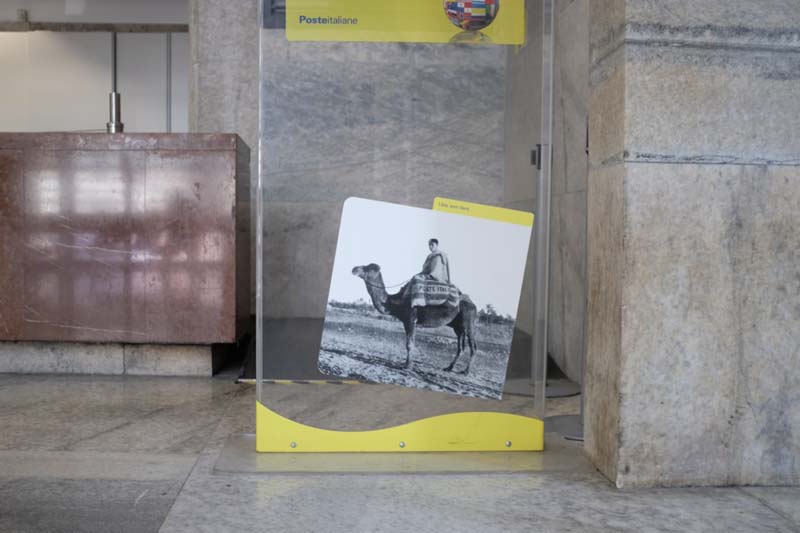

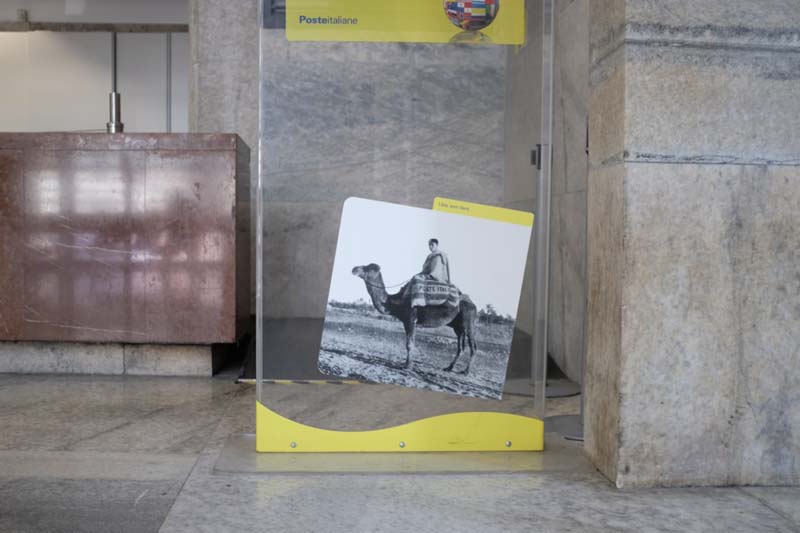

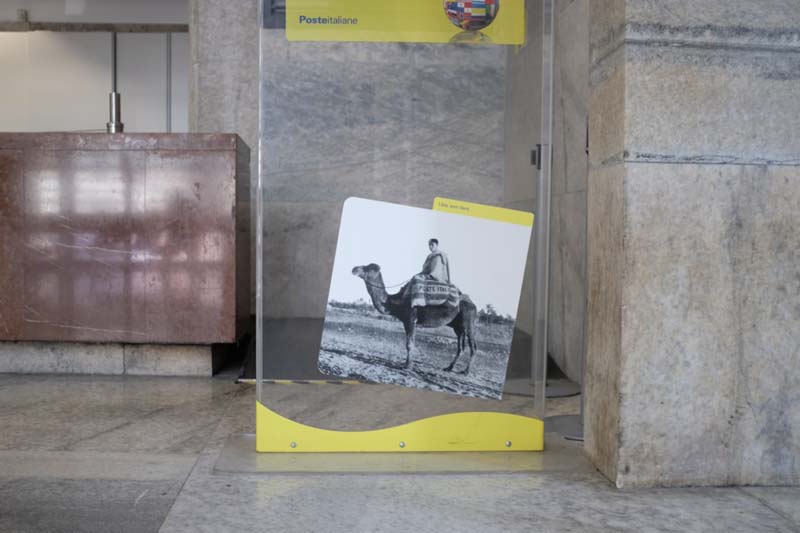

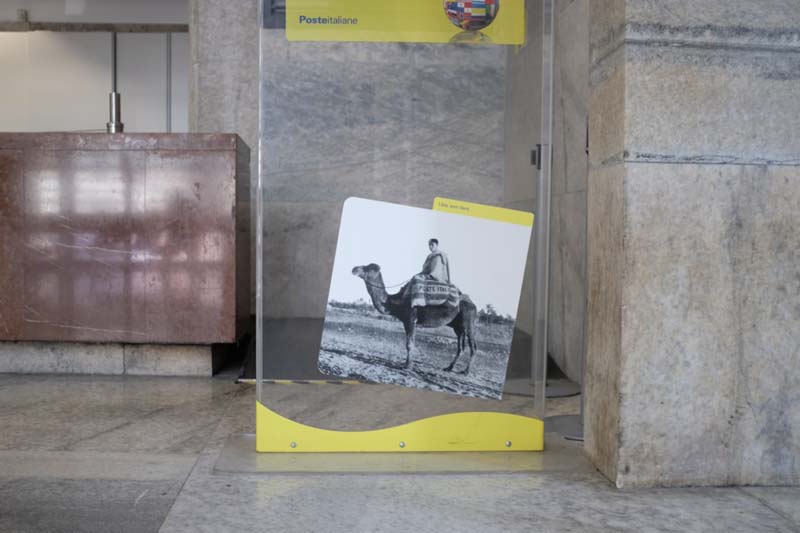

Just as I had stepped across infrastructural utility hole plates in Bari marked with fascist emblems, I encountered the same in Quartieri Spagnoli in Naples (Fig. 32). The scale of fascist-era construction remains unmistakable, especially the Palazzo delle Poste designed by Giuseppe Vaccaro and Gino Franzi. Its façade is clad in two stones, most striking at the elevation break where the inscription “ANNO 1936 XIV E. FASCISTA” proclaims the building’s completion (Fig. 33). While entering the post office in hopes of mailing books, I noticed how the building’s monumental entry bore fonts, signage, and linear geometries standard in other projects across Italy (Fig. 34). As I turned to leave, I saw the welcome sign, one I had nearly overlooked. Displayed under “Benvenuti,” a reprinted archival photograph of a young Libyan boy on a camel delivering “Poste Italiane,” captioned, “Libia, anni venti” (Fig. 35).

Fig. 32 – Steel plate bearing fascio in Quartieri Spagnoli, Napoli, Italy

Fig. 33 – Corner of Palazzo delle Poste to Piazza Giacomo Matteotti, Napoli, Italy

Fig. 34 – Entry to central post office, Palazzo delle Poste, Napoli, Italy

Fig. 35 – Archival image captioned “Libia, anni Venti” utilized on post office ‘Welcome’ signage, Palazzo delle Poste, Napoli, Italy

…a reverse overture…

The afterlives of empire move like the ‘ghibli’ itself—unseen, but not unfelt—flowing through the infrastructural veins of cities and the language of streets. These traces settle into the ordinary—fonts, fixtures, and names—often easy to overlook. What began as a word for a wind was recast through machinery until Ghibli’s origin thinned into abstraction. Sometimes it is the most ambient forces that carry the longest shadows. Among stone, steel, and speed, ‘ghibli’ remains as a residue of histories that resists stillness, traversing borders, people, and time.

‘Ghibli,’ a Libyan ‘Desert Wind,’ Lost in Translation Among Stone, Steel, and Speed

Sep 25, 2025

by

Amalie Elfallah, 2025 recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Amalie Elfallah is an architectural-urban designer from the Maryland–Washington D.C. area, which she acknowledges as the ancestral and unceded lands of the Piscataway-Conoy peoples. As an independent scholar, her research examines the socio-spatial imaginaries, constructions, and realities of Italian colonial Libya (1911–1943). She explores how narratives of contemporary [post]colonial Italy and Libya are concealed/embodied, forgotten/remembered, and erased/concretized.

As a recipient of the 2025 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Amalie plans to travel along the eastern coast of the United States before departing for Italy, China, Albania, Libya, and the Dodecanese Islands in Greece. Her itinerary focuses on tracing the built environment—buildings, monuments, public spaces, and street names—linked to a selection of Italy’s former colonies, protectorates, and concessions from the early 20th century. *All photographs are her own except otherwise noted. Some faces have been blurred solely to respect the people who give scale and context to the buildings and places she traveled.*

This writing weaves together my time in Italy. I am deeply grateful for the hospitality I encountered in every city and town I visited—from as north as Dro to as south as Syracuse. Thank you especially to SAH peers, colleagues, friends, and strangers who enriched my journey and reflections. Although I was unable to travel to Libya during my fellowship as originally planned, this piece gathers reflections that I hope to connect in the future.

_____________________________________________________

The name Ghibli is most commonly associated with Studio Ghibli (スタジオジブリ), the Japanese animation studio whose legacy has been manipulated by AI’s “Ghibli-style” imagery. The machine-generated drawings—created with a typewritten prompt and a single click—sharply contrast the studio’s hand-drawn films that unfold profound life-lessons. In the documentary “The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness” (2013), co-founder Hayao Miyazaki discusses the studio’s formation in the 1980s, casually recalling, “Ghibli is just a random name I got from an airplane.” But names, especially those that travel, rarely arrive in new places without being redefined.

In Libya, ‘ghibli’ (غبلي) is known as a “sandstorm” or a “desert wind blowing from the south.” Across some parts of the Sahara, ‘ghibli’ also refers to the “wind coming from Mecca,” deriving from the classical Arabic word ‘qibla’ (قبلة), meaning “direction.” By the late 1930s, ‘ghibli’ was Latinized—rather, Italianized—when the name was affixed to a military aircraft engineered by Gianni Caproni. The Caproni 'Ca. 309' Ghibli, according to Italy’s aeronautical military archives, was a “reconnaissance and liaison” aircraft utilized in Italy’s “North African colonies.” A word once referring to a natural atmospheric phenomenon was appropriated and attached to an instrument of war, transforming wind into steel and returning its name as a weaponized gust. Was Studio Ghibli’s title drawn from the wind itself, or from the machine that carried its name?

Fig. 1 – Propeller-shaped monument honoring aeronautical engineer Gianni Caproni, Arco, Italy

Fig. 2 – Garda Mountains and the Sarco River in Arco, Trentino-Alto Adige, Italy

Fig. 3 – Palazzo dell'Aeronautica Militare (c. 1938-41), Milan, Italy

Fig. 4 – Scene transition featuring the characters of Gianni Caproni and Jiro Horikoshi, ‘The Wind Rises’ (2013) by Ghibli Studio

I visited the monument honoring Caproni as a ‘Pioniere dell’Aeronautica’ in Arco (Fig. 1) while cycling along the paved path in the northern region of Trentino. The scenery unfolded beneath Ghibli-like clouds as I passed through the towering Garda Mountains (Fig. 2). It is easy to see how this breathtaking landscape inspired dreams of flight, especially for Caproni, who came from the region and later tested countless ambitious projects, such as a 100-passenger boat airliner. In reality, Caproni’s company significantly contributed to Italy’s Royal Air Force during military campaigns in Eritrea, Ethiopia, Libya, including across the Adriatic and Aegean Seas a century ago. As an architecture student at Politecnico di Milano, I had never considered the histories behind the marble façades and rationalist forms I passed by bike around Città Studi, like the Palazzo dell'Aeronautica Militare built in 1938 (Fig. 3). I overlooked the symbolism on the facade: the gladius sword, the propellers over the “M,” and a helmet resembling that from ‘Gladiator.’ The “Romanità” on the façade—so proudly displayed—escapes one’s notice just as everyday traffic insulates the hidden memory of Piazzale Loreto.

Studio Ghibli predominantly recasts Caproni as a reflective and visionary character in the animated film ‘The Wind Rises’ (2013). The first fictional encounter appears in the dreams of Japanese aeronautical engineer Jiro Horikoshi when Caproni leaps from a moving plane bearing the tricolor flag and lands beside a young Horikoshi as aircraft fly overhead. “Look at them,” Caproni says. “They will bomb the enemy city. Most of them won’t return. But the war will soon be over.” From a scene of destruction, the dream shifts to a passenger plane gliding past rolling hills beneath Ghibli’s iconic clouds. “This is my dream. When the war is over, I will build this,” Caproni declares. Inside, elegant curves and brightly upholstered seats furnish the interior (Fig. 4). “Magnificent, isn’t she?... Instead of bombs, she’ll carry passengers.” Caproni’s practice—designing machines for both war and transit—reveals how design moved between industrial cultures and civic life, often in tandem with the Italian Futurist movement.

Caproni’s practice most definitely shaped innovation in civic mobility post-WWI, which also echoes post-WWII innovations like Gio Ponti and Giulio Minoletti’s Arlecchino train (c. 1950s). At this year’s Salone del Mobile, the Arlecchino became the backdrop for the Prada Frames 2025 symposium at Milan’s Central Station. As curator Formafantasma noted, the train’s “exterior was informed by naval aerodynamics,” reflecting Italian design culture from fascist-era modernism and rationalism. The symposium also took place in the station’s Padiglione Reale, once reserved for royalty and fascist officials. Under the theme In Transit, it addressed “the complex relationship between ecology and design,” echoing the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale’s call for “decolonization and decarbonization.”

In practice, these venues' grandeur risked turning environmentalism into spectacle, overshadowing the ecological and historical ties within the architecture's legacy. From Venice to Milan, I looked for genuine and reparative involvement of Eritrean, Ethiopian, Somali, Libyan, Albanian, and other communities whose bodies and lands were exploited to forge Italy’s so-called “impero moderno.” Discourses advanced, yet exceptionalism merely shifted, as I saw ‘names’ performing reflection for an international stage. “Why are truly low-carbon, locally rooted practices—and the ethical inclusion of those whose histories are tied to these very structures—still so often absent in Italy?” It is a question that must be written and rewritten, not for lack of answers, but because making it clear demands so much that even the sharpest pencil dulls, worn down by the weight of explanation itself.

Passing through Milano Centrale in transit to Verona, I began to notice details I had once overlooked. Beneath the station’s vaulted ceiling, the Capitoline wolf appeared perfectly framed into the waiting hall (Fig. 5). On the platform, steel columns bore fasces with the inscription “CONSTRVI ANNO IX F.F.,” or “built in the ninth year of the Fascist Era,” i.e., 1931 (Fig. 6). These symbols, embedded into the station’s very fabric, reveals how fascism inscribed itself onto infrastructure, transforming transit into a quiet extension of state power.

Fig. 5 – Capitoline wolf seen in the waiting hall from platforms, Stazione Milano Centrale, Italy

Fig. 6 – Detail of steel column on the train platform, Stazione Milano Centrale, Italy

Fig. 7 – Section of commemorative wall ‘Binario 21,’ eastern side of Stazione Milano Centrale, Italy

Even today, amidst the rush of arrivals and departures, the eastern walls of ‘Binario 21’ retain juxtaposing traces: one plaque acknowledges the station’s role, Fascist-Italy’s complicity, as a transit point for Nazi-Germany’s Holocaust, while another, just to the left of the art-deco’d “gladius” sword—commemorates railway workers who served from “1940–1945” in the Italian–Ethiopian “war” (Fig. 7). But an Italo-Ethiopian, who may be commuting to Genova, passing by this wall might ask: “What of the years 1935–36? Did they forget chemical gas was weaponized in our mountains, against our peoples, like in the Cave of Zeret?” Stones and inscriptions, even when placed side by side, expose not only the ongoing colonial absences but also the Eurocentric ambiguities that persist in public space regarding national history “d’oltremare” or “overseas.”

In April, reminders of the Partigiani’s (partisan) “resistance” and “liberation” from Benito Mussolini’s fascist state, the Partito Nazionale Fascista (PNF), were unavoidable. While in Verona, intending to visit Carlo Scarpa’s Museo Castelvecchio, I encountered an exhibition about the 80th anniversary of the “Liberation from Nazi-Fascism (1943–1945).” The first exhibit space was a dark room screening 1938 film clips projected beside a white bust of Mussolini. The space carried a haunting stillness. Yet what unsettled me most was not this atmosphere—so familiar from archival encounters—but the curatorial decision to include works by Italian Futurist Renato di Bosso (Renato Righetti), despite his career being steeped in aeronautical and military-oriented productions.

Fig. 8 – Renato di Bosso aeropaintings featured in exhibit at Museo Castelvecchio, Verona, Italy

Fig. 9 – Italian futurist aeropainting depicting Italian colonial village in Libya, “Renato Di Bosso (Renato Righetti), In volo sul villaggio coloniale "M. Bianchi", 1938, oil on masonite, cm 89,5 x 100, Wolfsoniana – Palazzo Ducale Fondazione per la Cultura, Genova, 87.1070.5.1” (Source: courtesy of the Wolfsoniana Foundation, 2025)

The three “aeropaintings” on display in the main exhibit space (Fig. 8) reflected the dynamism of second-generation Italian Futurists. I immediately recognized Di Bosso’s work, already familiar with his “In volo sul villaggio coloniale ‘M. Bianchi’” (“Flying over the colonial village ‘M. Bianchi’”), recently exhibited at the Wolfsoniana Foundation in Liguria (Fig. 9). Though the painting does not explicitly name Libya or North Africa, the double-exposure of the built subject closely resembled one of the many standardized agricultural settlements constructed in Italy’s occupied territories. The painting, without a doubt, depicts the Tripolitanian rural center in Libya called ‘Villaggio Bianchi,’ designed by Umberto di Segni and named after Michele Bianchi, a founding member of the Fascist Party.

It is no coincidence that the painting was produced in 1938, the same year 20,000 Italians—known as the Ventimila—“immigrated” to standardized settlements along Libya’s coastline. This state-settlement program, under the Ente per la Colonizzazione della Libia with the INFPS, was certainly overseen by aviator-turned-governor Italo Balbo (famous for his transatlantic flight to Chicago, noted in my first SAH report). To de-mystify sanitized memories of Nazi–Fascist entanglements—generically remembered in April—it is worth recalling that Balbo hosted Nazi-German officials in Libya during the 1930s, some of whom were tried at Nuremberg. Some scholars suggest Nazi officials observed Fascist Italy’s racial and colonial policies of “ethnic reconstruction” and “demographic colonization.” However, it may have been all but normal, highly planned state-sponsored visits that involve nothing but incredulously staged parades, many of which remain archived by Luce. Nostalgic formalism—the whitewashed rural centers and farmhouses still described as “modern” or even “metaphysical”—ultimately fetishizes what were, at their core, standardized design packages built to serve Fascist Italy’s agenda overseas.

Fig. 10 – Ex-cinema Astra facade, Verona, Italy

Fig. 11 – ‘Via Adua’ street elevation, Verona, Italy

Fig. 12 – ‘Via Bengasi’ intersection, Verona, Italy

Fig. 13 – ‘Farmacia dell Cirenaica,’ Cyrenaica neighborhood in Bologna, Italy

Passing a former Cinema Astra (Fig. 10), I reflected on the persistence of rationalism across cities. At times, it signaled civic prominence; at others, decay. Yet it almost always reverberated the ideological legacies of fascism, where colonized places from Italy’s overseas campaigns resurfaced, their language reshaped to fit Italian speech in the streets. The phonetic flattening of ‘Via Adua’ (Fig. 11) shown in the work of Italo-Ethiopian Eritrean artist Jermay Michael Gabriel, ‘Via Adwa’ (2023), confronts this translation directly, crossing out the ‘u’ on the Carrara marble and marking the missing ‘w’ in black ink to restore its name.

I not only walked past ‘Via Adua’ in Verona, but cycled past the central station and through an industrial zone where I came upon ‘Via Bengasi’ (Fig.12). The setting felt remote, despite residences in the vicinity, and was disconnected from the city center, characterized by neglected buildings, patched walls, and overgrown vegetation. It reminded me of the enclave I had walked through in Turin. The second street sign, engraved in stone and mounted on a fence, was sub-labeled ‘Città d’Africa.’ These names—once markers of imperial claim—remain etched.

Unlike Verona and many cities where colonial-era street names remain intact, Bologna has uniquely addressed its colonial “inheritance,” acknowledged by collectives like Resistenza in Cirenaica. In the neighborhood of ‘Cirenaica,’ streets once named after Libyan cities—Tripoli, Derna, Bengasi, Homs, Zuara, Cirene—were renamed. They now have dual signs, pairing colonial names with Italian partisans’ names who resisted ‘Nazi-Fascism.’ For example, ‘Via Derna’ is now ‘Via Santa Vincenza: Caduto per la liberazione’ (Fallen for the Liberation). ‘Via Libia’ is the only sign unchanged and has remained since the 1920s, when workers settled in an enclave of the ‘old’ historic city center. Colonial names still surfaced in local businesses, including ‘Farmacia della Cirenaica’ (Fig. 13) and the ‘Mercato Cirenaica.’

Fig. 14 – Drawing by conscripted Eritrean Ascaro in Libya, Gariesus Gabriet’s “Conquest of the Oasis of Gialo, 1920-30s,” April 1928, Museo della Civiltà, Rome, Italy

Fig. 15 – ‘Libia’ Metro, Rome, Italy

Fig. 16 – Street signage of clustered former colonial territories, Rome, Italy

In Rome, I encountered objects in the former ‘Museo Coloniale,’ now the ‘Museo della Civiltà.’ Among the displayed upon my visit, a 1928 drawing by an Eritrean ascaro Gariesus Gabriet, “Conquest of the Oasis of Gialo,” stood out (Fig. 14). Riding the metro from the stone utopia of EUR to the 'Stazione Libia' neighborhood (Fig. 15), the drawing from the museum remained in mind as I walked along the streets scripted with “African” names—Viale Etiopia, Piazza Gondar, Via Libia, Via Eritrea (Fig. 16). The origin of Gabriet’s illustration is unclear—perhaps it was commissioned or solely to be collected and catalogued for the museum—but its display underscores how imperial gaze acted beyond conscription. Walking through housing blocks from the 1920s and ‘30s, threaded with familiar names, reveals how the rhythms of life soften the colonial weight inherited by the neighborhood.

Fig. 17 – Printed photograph of the typical lungomare balustrade, Darsena Toscana, Livorno, Italy

Fig. 18 – Fontana dei Mostri Marini by Pietro Tacca, Piazza Colonnella, Livorno, Italy

Fig. 19 – Monument of Ferdinand I de’ Medici, ‘Quattro Mori’ by Pietro Tacca, Piazza Michele, Livorno, Italy

Fascist-era constructions overlay earlier buildings of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany in Livorno. I was drawn in by the rational forms rising across the street from walking along the Darsena Toscana (Fig. 17). Along Via Grande towards the sea, market stands filled the openings to the covered walkways, demonstrating how rational facades became seamlessly integrated and juxtaposed. A replica of Pietro Tacca’s ‘Fontana dei Mostri Marini,’ the original of which is located in Florence (Fig. 18), is situated near another work by Tacca at Piazzale Micheli. Tacca’s ‘Four Moors’ (Fig. 19) was installed on a monument dedicated to Ferdinando I de’ Medici in the seventeenth century. A man, carved from Carrara marble, stands tall over four men in bronze, crouched and chained at the corners of a rectangular pedestal. A sign near the ‘4 Moor’ café describes the “moors” as “pirates mainly from the North African provinces of the Ottoman Empire.” The monument’s material contrasts and its composition of elevation and restraint render the disparity it represents unmistakable: a visual language of subjugation, incarceration, and hierarchies of race. I watched families and tourists pause to take photographs with the monument in the background, their casual gestures softening the edges of the scene behind them. To describe oneself as Italo-Arab or Italo-African—“African” long steeped in ongoing racial stereotypes—means, inescapably, feeling the weight this monument still pressing into the present, even as others dismiss it with a casual, ‘Ma questa è la storia della città?’

Fig. 20 – Museo Civico Giovanni Fattori, Livorno, Italy

Fig. 21 – Photograph found in Mercantino depicting ‘Fontana della Gazella’ in Tripoli (Libya), Piazza Luigi Orlando, Livorno, Italy

I mainly visited Livorno to see the original model of the ‘Fontana della Gazzella’ (c. 1934) by Livornese sculptor Angiolo Vannetti, which became the reference to what stood along the ‘lungomare’ in Tripoli, Libya. Vannetti’s working model is preserved at the 19th-century Villa Mimbelli in Museo Civico Giovanni Fattori (Fig. 20). Unfortunately, building renovations prevented me from seeing it in person. The statue in Libya, installed during the colonial era, stood until it was destroyed by religious extremists in 2014. Throughout the year, memories of that era, especially the sculpture, resurface in Facebook groups dedicated to Italy’s past—spaces where Italians and Libyans, many now over sixty, share stories, recipes, and greetings beyond the “difficult” parts of history. For a moment, Italians and Libyans were neighbors, as I heard a Libyan recall their neighbor giving their humble family a ‘panettone’ around Christmas time many many years ago. The sculpture continues to be reimagined by Libyan artists in countless works, most recently by Born in Exile, since its disappearance.

Not far from the museum, at the street market in Piazza Luigi Orlando, I sifted through boxes of antique postcards. By chance, I came across an image of the very sculpture that had brought me to Livorno—the ‘Fontana della Gazella’ in Tripoli (Fig. 21). This moment echoed the persistence of colonial fragments or remnants of “wars” overseas, which are now traded casually as collectibles across flea markets.

Fig. 22 –Reenactment preparations of ‘Difesa di Livorno’ in Piazza della Repubblica, Livorno, Italy

Fig. 23 – Building corner, Via Giosue Carducci & Via Vittorio Alfieri, Livorno, Italy

Crossing Piazza della Repubblica, men in camouflage pants were preparing a stage as chairs were being unloaded from a truck into the plaza, just in front of a rationalist palazzo (Fig. 22). Under the colonnade of a neoclassical palazzo, across the plaza, members of a historical reenactment group in Risorgimento-era costume gathered in front of the storefront ‘Comunità Senegalese Livorno e Provincia.’ Later, I learned the performance marked the 175th anniversary of the “Difesa di Livorno,” restaging the city’s “resistance” during the Risorgimento. It was not only palaces but residences, rounded buildings, demarking street corners, that became a visual signature I would recognize later in other cities built during the 1920s and 1930s (Fig. 23). In passing to depart Livorno, steps away from the train station, more familiar streets: ‘Via Bengasi’ and ‘Via Tripoli.’

The National Central Library of Florence (BNCF) holds a prominent position along the Arno. The negative space of Piazza dei Cavalleggeri opens toward the eastern edge of the city, allowing traffic to flow in. Hidden behind the plot along the riverfront is ‘Via Tripoli’ (Fig. 24). The plaque marks the street, which runs parallel to the Arno and leads toward the library’s piazza. According to scholars at the European University Institute’s ‘Post-colonial Italy: Mapping Colonial Heritage’ project, “the Florentine city government under the mayor Filippo Corsini decided to rename the street into Via Tripoli to commemorate a successful conquest” during Italy’s “war” with the Ottomans.

Fig. 24 – Via Tripoli feeding into the front plaza of Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, Florence, Italy

Fig. 25 –Detail of ‘The Divine Comedy’ and Fascio symbol depicted on bronze crest, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, Florence, Italy

Fig. 26 – View of Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze façade across the Arno, Florence, Italy

Continuing from Via Tripoli across the library’s façade, one encounters bronze-adorned crests affixed to the building. One inscribes “Divina Commedia,” a renowned Italian text by Dante Alighieri, near it, another crest bearing a bundle-axe fascio (Fig. 25). The PNF transformed Dante into a national icon, particularly in Florence, despite his exile from the city in the 14th century. I was reminded of this paradox months later in my last stop of the fellowship when—through a bookstore window in Casablanca—I saw Dante on the translated copy of Edward Said’s book ‘Reflections on Exile and Other Essays’ (2000) in Arabic. It left me wondering: why did Said choose Dante on the cover for a ‘meditation’ on ‘exile’? And why did a Fascist-era institution celebrate Florence’s ‘wandering humanist’ while unleashing its own ‘inferno’ overseas? The library, positioned prominently along the Arno, becomes a telling example of how institutions assemble narrative into public space (Fig. 26).

I walked across the city to the first archive I visited as a graduate student at the former ‘Istituto Agronomico per l’Oltremare’ (IAO), known today as ‘Agenzia Italiana per la Cooperazione allo Sviluppo, AICS’ (Fig. 27). Looking at the entry past my reflection, I could see green marble stairs rising into the hall I had walked past years earlier. Palm motifs appear on the grilles of the institute’s front doors—echoing those on the light fixture at Bologna’s ‘Farmacia della Cirenaica’—a lingering emblem of exoticization often used to reference lands “d’oltremare” iconographically. Even if I wanted to enter, a sign read “Campanello Guasto” or “broken doorbell” (Fig. 28). These signs of closure reveal what happens when institutions are left suspended due to a lack of investment. Neither erased nor fully engaged, but locked behind closed doors.

Fig. 27 – Roundabout in front of the former Istituto Agronomico per l'Oltremare, Florence, Italy

Fig. 28 – Looking into the “permanently closed” ex-Istituto Agronomico per l'Oltremare, Florence, Italy

After my time in the Dodecanese and Albania, I crossed the Adriatic to Bari. I recall walking along the seafront promenade, passing the fortified city, ‘la città vecchia,’ which reminded me of other Mediterranean ports like Tripoli, where old city walls meet the sea and its ‘modern’ extension, built throughout the early 20th century. Along the ‘lungomare’ extending the city south, rationalism’s footprint outlined the route to the nearest ‘spiaggia libera’ or public beach (Fig. 29/30). The institutional blocs were tied into the neighborhood by streets like Via Libia, Via Durazzo, Via Addis Abeba, and Via Somalia, reflecting the clusters of colonial names I had seen in regions north of Puglia.

Fig. 29/30 – Along the lungomare promenade, Bari, Italy

Fig. 31 – Volkswagen Beetles from Libya seen at the Apulia Volks Club, Bari, Piazza Libertà, Bari, Italy

I passed the Apulia Volks Club Bari gathering in Piazza Libertà (Fig. 31) and saw an institutional building stenciled for the first time, a symbol of broken rationality. Three Libyan-plate Volkswagen Beetles with club stickers from Derna and Tripoli caught my eye. Unlike Algerians in France, Angolans in Portugal, and Ethiopians in Italy, Libyan presence is rare; the country did not receive a large diasporic community after the Italian occupation ended in 1943.

Just as I had stepped across infrastructural utility hole plates in Bari marked with fascist emblems, I encountered the same in Quartieri Spagnoli in Naples (Fig. 32). The scale of fascist-era construction remains unmistakable, especially the Palazzo delle Poste designed by Giuseppe Vaccaro and Gino Franzi. Its façade is clad in two stones, most striking at the elevation break where the inscription “ANNO 1936 XIV E. FASCISTA” proclaims the building’s completion (Fig. 33). While entering the post office in hopes of mailing books, I noticed how the building’s monumental entry bore fonts, signage, and linear geometries standard in other projects across Italy (Fig. 34). As I turned to leave, I saw the welcome sign, one I had nearly overlooked. Displayed under “Benvenuti,” a reprinted archival photograph of a young Libyan boy on a camel delivering “Poste Italiane,” captioned, “Libia, anni venti” (Fig. 35).

Fig. 32 – Steel plate bearing fascio in Quartieri Spagnoli, Napoli, Italy

Fig. 33 – Corner of Palazzo delle Poste to Piazza Giacomo Matteotti, Napoli, Italy

Fig. 34 – Entry to central post office, Palazzo delle Poste, Napoli, Italy

Fig. 35 – Archival image captioned “Libia, anni Venti” utilized on post office ‘Welcome’ signage, Palazzo delle Poste, Napoli, Italy

…a reverse overture…

The afterlives of empire move like the ‘ghibli’ itself—unseen, but not unfelt—flowing through the infrastructural veins of cities and the language of streets. These traces settle into the ordinary—fonts, fixtures, and names—often easy to overlook. What began as a word for a wind was recast through machinery until Ghibli’s origin thinned into abstraction. Sometimes it is the most ambient forces that carry the longest shadows. Among stone, steel, and speed, ‘ghibli’ remains as a residue of histories that resists stillness, traversing borders, people, and time.

2024 Recipients

‘Ghibli,’ a Libyan ‘Desert Wind,’ Lost in Translation Among Stone, Steel, and Speed

Sep 25, 2025

by

Amalie Elfallah, 2025 recipient of SAH's H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Amalie Elfallah is an architectural-urban designer from the Maryland–Washington D.C. area, which she acknowledges as the ancestral and unceded lands of the Piscataway-Conoy peoples. As an independent scholar, her research examines the socio-spatial imaginaries, constructions, and realities of Italian colonial Libya (1911–1943). She explores how narratives of contemporary [post]colonial Italy and Libya are concealed/embodied, forgotten/remembered, and erased/concretized.

As a recipient of the 2025 H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship, Amalie plans to travel along the eastern coast of the United States before departing for Italy, China, Albania, Libya, and the Dodecanese Islands in Greece. Her itinerary focuses on tracing the built environment—buildings, monuments, public spaces, and street names—linked to a selection of Italy’s former colonies, protectorates, and concessions from the early 20th century. *All photographs are her own except otherwise noted. Some faces have been blurred solely to respect the people who give scale and context to the buildings and places she traveled.*

This writing weaves together my time in Italy. I am deeply grateful for the hospitality I encountered in every city and town I visited—from as north as Dro to as south as Syracuse. Thank you especially to SAH peers, colleagues, friends, and strangers who enriched my journey and reflections. Although I was unable to travel to Libya during my fellowship as originally planned, this piece gathers reflections that I hope to connect in the future.

_____________________________________________________

The name Ghibli is most commonly associated with Studio Ghibli (スタジオジブリ), the Japanese animation studio whose legacy has been manipulated by AI’s “Ghibli-style” imagery. The machine-generated drawings—created with a typewritten prompt and a single click—sharply contrast the studio’s hand-drawn films that unfold profound life-lessons. In the documentary “The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness” (2013), co-founder Hayao Miyazaki discusses the studio’s formation in the 1980s, casually recalling, “Ghibli is just a random name I got from an airplane.” But names, especially those that travel, rarely arrive in new places without being redefined.

In Libya, ‘ghibli’ (غبلي) is known as a “sandstorm” or a “desert wind blowing from the south.” Across some parts of the Sahara, ‘ghibli’ also refers to the “wind coming from Mecca,” deriving from the classical Arabic word ‘qibla’ (قبلة), meaning “direction.” By the late 1930s, ‘ghibli’ was Latinized—rather, Italianized—when the name was affixed to a military aircraft engineered by Gianni Caproni. The Caproni 'Ca. 309' Ghibli, according to Italy’s aeronautical military archives, was a “reconnaissance and liaison” aircraft utilized in Italy’s “North African colonies.” A word once referring to a natural atmospheric phenomenon was appropriated and attached to an instrument of war, transforming wind into steel and returning its name as a weaponized gust. Was Studio Ghibli’s title drawn from the wind itself, or from the machine that carried its name?

Fig. 1 – Propeller-shaped monument honoring aeronautical engineer Gianni Caproni, Arco, Italy

Fig. 2 – Garda Mountains and the Sarco River in Arco, Trentino-Alto Adige, Italy

Fig. 3 – Palazzo dell'Aeronautica Militare (c. 1938-41), Milan, Italy

Fig. 4 – Scene transition featuring the characters of Gianni Caproni and Jiro Horikoshi, ‘The Wind Rises’ (2013) by Ghibli Studio

I visited the monument honoring Caproni as a ‘Pioniere dell’Aeronautica’ in Arco (Fig. 1) while cycling along the paved path in the northern region of Trentino. The scenery unfolded beneath Ghibli-like clouds as I passed through the towering Garda Mountains (Fig. 2). It is easy to see how this breathtaking landscape inspired dreams of flight, especially for Caproni, who came from the region and later tested countless ambitious projects, such as a 100-passenger boat airliner. In reality, Caproni’s company significantly contributed to Italy’s Royal Air Force during military campaigns in Eritrea, Ethiopia, Libya, including across the Adriatic and Aegean Seas a century ago. As an architecture student at Politecnico di Milano, I had never considered the histories behind the marble façades and rationalist forms I passed by bike around Città Studi, like the Palazzo dell'Aeronautica Militare built in 1938 (Fig. 3). I overlooked the symbolism on the facade: the gladius sword, the propellers over the “M,” and a helmet resembling that from ‘Gladiator.’ The “Romanità” on the façade—so proudly displayed—escapes one’s notice just as everyday traffic insulates the hidden memory of Piazzale Loreto.

Studio Ghibli predominantly recasts Caproni as a reflective and visionary character in the animated film ‘The Wind Rises’ (2013). The first fictional encounter appears in the dreams of Japanese aeronautical engineer Jiro Horikoshi when Caproni leaps from a moving plane bearing the tricolor flag and lands beside a young Horikoshi as aircraft fly overhead. “Look at them,” Caproni says. “They will bomb the enemy city. Most of them won’t return. But the war will soon be over.” From a scene of destruction, the dream shifts to a passenger plane gliding past rolling hills beneath Ghibli’s iconic clouds. “This is my dream. When the war is over, I will build this,” Caproni declares. Inside, elegant curves and brightly upholstered seats furnish the interior (Fig. 4). “Magnificent, isn’t she?... Instead of bombs, she’ll carry passengers.” Caproni’s practice—designing machines for both war and transit—reveals how design moved between industrial cultures and civic life, often in tandem with the Italian Futurist movement.

Caproni’s practice most definitely shaped innovation in civic mobility post-WWI, which also echoes post-WWII innovations like Gio Ponti and Giulio Minoletti’s Arlecchino train (c. 1950s). At this year’s Salone del Mobile, the Arlecchino became the backdrop for the Prada Frames 2025 symposium at Milan’s Central Station. As curator Formafantasma noted, the train’s “exterior was informed by naval aerodynamics,” reflecting Italian design culture from fascist-era modernism and rationalism. The symposium also took place in the station’s Padiglione Reale, once reserved for royalty and fascist officials. Under the theme In Transit, it addressed “the complex relationship between ecology and design,” echoing the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale’s call for “decolonization and decarbonization.”

In practice, these venues' grandeur risked turning environmentalism into spectacle, overshadowing the ecological and historical ties within the architecture's legacy. From Venice to Milan, I looked for genuine and reparative involvement of Eritrean, Ethiopian, Somali, Libyan, Albanian, and other communities whose bodies and lands were exploited to forge Italy’s so-called “impero moderno.” Discourses advanced, yet exceptionalism merely shifted, as I saw ‘names’ performing reflection for an international stage. “Why are truly low-carbon, locally rooted practices—and the ethical inclusion of those whose histories are tied to these very structures—still so often absent in Italy?” It is a question that must be written and rewritten, not for lack of answers, but because making it clear demands so much that even the sharpest pencil dulls, worn down by the weight of explanation itself.

Passing through Milano Centrale in transit to Verona, I began to notice details I had once overlooked. Beneath the station’s vaulted ceiling, the Capitoline wolf appeared perfectly framed into the waiting hall (Fig. 5). On the platform, steel columns bore fasces with the inscription “CONSTRVI ANNO IX F.F.,” or “built in the ninth year of the Fascist Era,” i.e., 1931 (Fig. 6). These symbols, embedded into the station’s very fabric, reveals how fascism inscribed itself onto infrastructure, transforming transit into a quiet extension of state power.

Fig. 5 – Capitoline wolf seen in the waiting hall from platforms, Stazione Milano Centrale, Italy

Fig. 6 – Detail of steel column on the train platform, Stazione Milano Centrale, Italy

Fig. 7 – Section of commemorative wall ‘Binario 21,’ eastern side of Stazione Milano Centrale, Italy

Even today, amidst the rush of arrivals and departures, the eastern walls of ‘Binario 21’ retain juxtaposing traces: one plaque acknowledges the station’s role, Fascist-Italy’s complicity, as a transit point for Nazi-Germany’s Holocaust, while another, just to the left of the art-deco’d “gladius” sword—commemorates railway workers who served from “1940–1945” in the Italian–Ethiopian “war” (Fig. 7). But an Italo-Ethiopian, who may be commuting to Genova, passing by this wall might ask: “What of the years 1935–36? Did they forget chemical gas was weaponized in our mountains, against our peoples, like in the Cave of Zeret?” Stones and inscriptions, even when placed side by side, expose not only the ongoing colonial absences but also the Eurocentric ambiguities that persist in public space regarding national history “d’oltremare” or “overseas.”

In April, reminders of the Partigiani’s (partisan) “resistance” and “liberation” from Benito Mussolini’s fascist state, the Partito Nazionale Fascista (PNF), were unavoidable. While in Verona, intending to visit Carlo Scarpa’s Museo Castelvecchio, I encountered an exhibition about the 80th anniversary of the “Liberation from Nazi-Fascism (1943–1945).” The first exhibit space was a dark room screening 1938 film clips projected beside a white bust of Mussolini. The space carried a haunting stillness. Yet what unsettled me most was not this atmosphere—so familiar from archival encounters—but the curatorial decision to include works by Italian Futurist Renato di Bosso (Renato Righetti), despite his career being steeped in aeronautical and military-oriented productions.

Fig. 8 – Renato di Bosso aeropaintings featured in exhibit at Museo Castelvecchio, Verona, Italy

Fig. 9 – Italian futurist aeropainting depicting Italian colonial village in Libya, “Renato Di Bosso (Renato Righetti), In volo sul villaggio coloniale "M. Bianchi", 1938, oil on masonite, cm 89,5 x 100, Wolfsoniana – Palazzo Ducale Fondazione per la Cultura, Genova, 87.1070.5.1” (Source: courtesy of the Wolfsoniana Foundation, 2025)

The three “aeropaintings” on display in the main exhibit space (Fig. 8) reflected the dynamism of second-generation Italian Futurists. I immediately recognized Di Bosso’s work, already familiar with his “In volo sul villaggio coloniale ‘M. Bianchi’” (“Flying over the colonial village ‘M. Bianchi’”), recently exhibited at the Wolfsoniana Foundation in Liguria (Fig. 9). Though the painting does not explicitly name Libya or North Africa, the double-exposure of the built subject closely resembled one of the many standardized agricultural settlements constructed in Italy’s occupied territories. The painting, without a doubt, depicts the Tripolitanian rural center in Libya called ‘Villaggio Bianchi,’ designed by Umberto di Segni and named after Michele Bianchi, a founding member of the Fascist Party.

It is no coincidence that the painting was produced in 1938, the same year 20,000 Italians—known as the Ventimila—“immigrated” to standardized settlements along Libya’s coastline. This state-settlement program, under the Ente per la Colonizzazione della Libia with the INFPS, was certainly overseen by aviator-turned-governor Italo Balbo (famous for his transatlantic flight to Chicago, noted in my first SAH report). To de-mystify sanitized memories of Nazi–Fascist entanglements—generically remembered in April—it is worth recalling that Balbo hosted Nazi-German officials in Libya during the 1930s, some of whom were tried at Nuremberg. Some scholars suggest Nazi officials observed Fascist Italy’s racial and colonial policies of “ethnic reconstruction” and “demographic colonization.” However, it may have been all but normal, highly planned state-sponsored visits that involve nothing but incredulously staged parades, many of which remain archived by Luce. Nostalgic formalism—the whitewashed rural centers and farmhouses still described as “modern” or even “metaphysical”—ultimately fetishizes what were, at their core, standardized design packages built to serve Fascist Italy’s agenda overseas.

Fig. 10 – Ex-cinema Astra facade, Verona, Italy

Fig. 11 – ‘Via Adua’ street elevation, Verona, Italy

Fig. 12 – ‘Via Bengasi’ intersection, Verona, Italy

Fig. 13 – ‘Farmacia dell Cirenaica,’ Cyrenaica neighborhood in Bologna, Italy

Passing a former Cinema Astra (Fig. 10), I reflected on the persistence of rationalism across cities. At times, it signaled civic prominence; at others, decay. Yet it almost always reverberated the ideological legacies of fascism, where colonized places from Italy’s overseas campaigns resurfaced, their language reshaped to fit Italian speech in the streets. The phonetic flattening of ‘Via Adua’ (Fig. 11) shown in the work of Italo-Ethiopian Eritrean artist Jermay Michael Gabriel, ‘Via Adwa’ (2023), confronts this translation directly, crossing out the ‘u’ on the Carrara marble and marking the missing ‘w’ in black ink to restore its name.

I not only walked past ‘Via Adua’ in Verona, but cycled past the central station and through an industrial zone where I came upon ‘Via Bengasi’ (Fig.12). The setting felt remote, despite residences in the vicinity, and was disconnected from the city center, characterized by neglected buildings, patched walls, and overgrown vegetation. It reminded me of the enclave I had walked through in Turin. The second street sign, engraved in stone and mounted on a fence, was sub-labeled ‘Città d’Africa.’ These names—once markers of imperial claim—remain etched.

Unlike Verona and many cities where colonial-era street names remain intact, Bologna has uniquely addressed its colonial “inheritance,” acknowledged by collectives like Resistenza in Cirenaica. In the neighborhood of ‘Cirenaica,’ streets once named after Libyan cities—Tripoli, Derna, Bengasi, Homs, Zuara, Cirene—were renamed. They now have dual signs, pairing colonial names with Italian partisans’ names who resisted ‘Nazi-Fascism.’ For example, ‘Via Derna’ is now ‘Via Santa Vincenza: Caduto per la liberazione’ (Fallen for the Liberation). ‘Via Libia’ is the only sign unchanged and has remained since the 1920s, when workers settled in an enclave of the ‘old’ historic city center. Colonial names still surfaced in local businesses, including ‘Farmacia della Cirenaica’ (Fig. 13) and the ‘Mercato Cirenaica.’

Fig. 14 – Drawing by conscripted Eritrean Ascaro in Libya, Gariesus Gabriet’s “Conquest of the Oasis of Gialo, 1920-30s,” April 1928, Museo della Civiltà, Rome, Italy

Fig. 15 – ‘Libia’ Metro, Rome, Italy

Fig. 16 – Street signage of clustered former colonial territories, Rome, Italy

In Rome, I encountered objects in the former ‘Museo Coloniale,’ now the ‘Museo della Civiltà.’ Among the displayed upon my visit, a 1928 drawing by an Eritrean ascaro Gariesus Gabriet, “Conquest of the Oasis of Gialo,” stood out (Fig. 14). Riding the metro from the stone utopia of EUR to the 'Stazione Libia' neighborhood (Fig. 15), the drawing from the museum remained in mind as I walked along the streets scripted with “African” names—Viale Etiopia, Piazza Gondar, Via Libia, Via Eritrea (Fig. 16). The origin of Gabriet’s illustration is unclear—perhaps it was commissioned or solely to be collected and catalogued for the museum—but its display underscores how imperial gaze acted beyond conscription. Walking through housing blocks from the 1920s and ‘30s, threaded with familiar names, reveals how the rhythms of life soften the colonial weight inherited by the neighborhood.

Fig. 17 – Printed photograph of the typical lungomare balustrade, Darsena Toscana, Livorno, Italy

Fig. 18 – Fontana dei Mostri Marini by Pietro Tacca, Piazza Colonnella, Livorno, Italy

Fig. 19 – Monument of Ferdinand I de’ Medici, ‘Quattro Mori’ by Pietro Tacca, Piazza Michele, Livorno, Italy

Fascist-era constructions overlay earlier buildings of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany in Livorno. I was drawn in by the rational forms rising across the street from walking along the Darsena Toscana (Fig. 17). Along Via Grande towards the sea, market stands filled the openings to the covered walkways, demonstrating how rational facades became seamlessly integrated and juxtaposed. A replica of Pietro Tacca’s ‘Fontana dei Mostri Marini,’ the original of which is located in Florence (Fig. 18), is situated near another work by Tacca at Piazzale Micheli. Tacca’s ‘Four Moors’ (Fig. 19) was installed on a monument dedicated to Ferdinando I de’ Medici in the seventeenth century. A man, carved from Carrara marble, stands tall over four men in bronze, crouched and chained at the corners of a rectangular pedestal. A sign near the ‘4 Moor’ café describes the “moors” as “pirates mainly from the North African provinces of the Ottoman Empire.” The monument’s material contrasts and its composition of elevation and restraint render the disparity it represents unmistakable: a visual language of subjugation, incarceration, and hierarchies of race. I watched families and tourists pause to take photographs with the monument in the background, their casual gestures softening the edges of the scene behind them. To describe oneself as Italo-Arab or Italo-African—“African” long steeped in ongoing racial stereotypes—means, inescapably, feeling the weight this monument still pressing into the present, even as others dismiss it with a casual, ‘Ma questa è la storia della città?’

Fig. 20 – Museo Civico Giovanni Fattori, Livorno, Italy

Fig. 21 – Photograph found in Mercantino depicting ‘Fontana della Gazella’ in Tripoli (Libya), Piazza Luigi Orlando, Livorno, Italy

I mainly visited Livorno to see the original model of the ‘Fontana della Gazzella’ (c. 1934) by Livornese sculptor Angiolo Vannetti, which became the reference to what stood along the ‘lungomare’ in Tripoli, Libya. Vannetti’s working model is preserved at the 19th-century Villa Mimbelli in Museo Civico Giovanni Fattori (Fig. 20). Unfortunately, building renovations prevented me from seeing it in person. The statue in Libya, installed during the colonial era, stood until it was destroyed by religious extremists in 2014. Throughout the year, memories of that era, especially the sculpture, resurface in Facebook groups dedicated to Italy’s past—spaces where Italians and Libyans, many now over sixty, share stories, recipes, and greetings beyond the “difficult” parts of history. For a moment, Italians and Libyans were neighbors, as I heard a Libyan recall their neighbor giving their humble family a ‘panettone’ around Christmas time many many years ago. The sculpture continues to be reimagined by Libyan artists in countless works, most recently by Born in Exile, since its disappearance.

Not far from the museum, at the street market in Piazza Luigi Orlando, I sifted through boxes of antique postcards. By chance, I came across an image of the very sculpture that had brought me to Livorno—the ‘Fontana della Gazella’ in Tripoli (Fig. 21). This moment echoed the persistence of colonial fragments or remnants of “wars” overseas, which are now traded casually as collectibles across flea markets.

Fig. 22 –Reenactment preparations of ‘Difesa di Livorno’ in Piazza della Repubblica, Livorno, Italy

Fig. 23 – Building corner, Via Giosue Carducci & Via Vittorio Alfieri, Livorno, Italy

Crossing Piazza della Repubblica, men in camouflage pants were preparing a stage as chairs were being unloaded from a truck into the plaza, just in front of a rationalist palazzo (Fig. 22). Under the colonnade of a neoclassical palazzo, across the plaza, members of a historical reenactment group in Risorgimento-era costume gathered in front of the storefront ‘Comunità Senegalese Livorno e Provincia.’ Later, I learned the performance marked the 175th anniversary of the “Difesa di Livorno,” restaging the city’s “resistance” during the Risorgimento. It was not only palaces but residences, rounded buildings, demarking street corners, that became a visual signature I would recognize later in other cities built during the 1920s and 1930s (Fig. 23). In passing to depart Livorno, steps away from the train station, more familiar streets: ‘Via Bengasi’ and ‘Via Tripoli.’

The National Central Library of Florence (BNCF) holds a prominent position along the Arno. The negative space of Piazza dei Cavalleggeri opens toward the eastern edge of the city, allowing traffic to flow in. Hidden behind the plot along the riverfront is ‘Via Tripoli’ (Fig. 24). The plaque marks the street, which runs parallel to the Arno and leads toward the library’s piazza. According to scholars at the European University Institute’s ‘Post-colonial Italy: Mapping Colonial Heritage’ project, “the Florentine city government under the mayor Filippo Corsini decided to rename the street into Via Tripoli to commemorate a successful conquest” during Italy’s “war” with the Ottomans.

Fig. 24 – Via Tripoli feeding into the front plaza of Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, Florence, Italy

Fig. 25 –Detail of ‘The Divine Comedy’ and Fascio symbol depicted on bronze crest, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, Florence, Italy

Fig. 26 – View of Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze façade across the Arno, Florence, Italy

Continuing from Via Tripoli across the library’s façade, one encounters bronze-adorned crests affixed to the building. One inscribes “Divina Commedia,” a renowned Italian text by Dante Alighieri, near it, another crest bearing a bundle-axe fascio (Fig. 25). The PNF transformed Dante into a national icon, particularly in Florence, despite his exile from the city in the 14th century. I was reminded of this paradox months later in my last stop of the fellowship when—through a bookstore window in Casablanca—I saw Dante on the translated copy of Edward Said’s book ‘Reflections on Exile and Other Essays’ (2000) in Arabic. It left me wondering: why did Said choose Dante on the cover for a ‘meditation’ on ‘exile’? And why did a Fascist-era institution celebrate Florence’s ‘wandering humanist’ while unleashing its own ‘inferno’ overseas? The library, positioned prominently along the Arno, becomes a telling example of how institutions assemble narrative into public space (Fig. 26).

I walked across the city to the first archive I visited as a graduate student at the former ‘Istituto Agronomico per l’Oltremare’ (IAO), known today as ‘Agenzia Italiana per la Cooperazione allo Sviluppo, AICS’ (Fig. 27). Looking at the entry past my reflection, I could see green marble stairs rising into the hall I had walked past years earlier. Palm motifs appear on the grilles of the institute’s front doors—echoing those on the light fixture at Bologna’s ‘Farmacia della Cirenaica’—a lingering emblem of exoticization often used to reference lands “d’oltremare” iconographically. Even if I wanted to enter, a sign read “Campanello Guasto” or “broken doorbell” (Fig. 28). These signs of closure reveal what happens when institutions are left suspended due to a lack of investment. Neither erased nor fully engaged, but locked behind closed doors.

Fig. 27 – Roundabout in front of the former Istituto Agronomico per l'Oltremare, Florence, Italy