-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarshipLatest Issue:

-

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programsMember Programs

-

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

District, Route, Corridor: Port Architectures and Heritage Strategies in Chile

In the Yokohama Port Museum, there is a row of framed archival photographs from the United States occupation of the Yokohama port and harbor after World War II. These artful black and white images capture the bizarre urban condition of the occupation—leisurely lawn parties in the fenced American compound against the backdrop of bombed out buildings and everyday Japanese hardship. Those stark images stuck with me in part because of how different they were from the rest of the Port Museum, which is a well-orchestrated profusion of digital interactives and pleasingly haptic physical models. But I think the main reason I’m still pondering those photographs two months later is that at some basic level, they conveyed the cultural, economic, and political messiness not just of Yokohama’s port in the late 1940s, but of industrialized port cities in general. As someone who grew up landlocked in the desert of the American Southwest, it has taken me until this trip to appreciate the extent to which industrial and post-industrial port cities lie at the fragile nexus of local and global economic forces, constituting surprisingly vulnerable and yet adaptable urban entities.

Across the globe, as historic ports have lost economic activity, changed function, or undergone retrofitting for containerization, redevelopment and spatial reconfiguration have become critical to the survival of ports and their surrounding urban areas. Today, Yokohama’s port has entered a new economic and architectural phase. While industrial shipping (particularly the export of Japanese cars) is still part of the equation, those functions have been consolidated into the southern part of the bay. In Yokohama, much of the harbor has been taken over by commercial and touristic programs.

Adjacent to the Port Museum, a nondescript and somewhat hidden building, is the impressively preserved Nippon Maru, a 1930 vessel that was for many years used to train the Japanese navy. A Ferris wheel turns steadily over a small amusement park, next to several new retail complexes. A short walk away, at the Cup Noodles Museum, architectural minimalism meets consumerist maximalism in one of Yokohama’s most popular present-day attractions. The red brick warehouses (constructed 1911 and 1913, repaired after the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923) have been converted into claustrophobia-inducing boutique shopping malls. On the day I visited, the atmosphere was festive. The Christmas shopping season had started and the plaza between the two warehouses was filled with a street market and a bevy of food trucks.

From the redeveloped commercial area, the present-day shipping port is shielded from view by the International Passenger Terminal, a sprawling edifice that juts 430 meters into the harbor. Designed by Farshid Moussavi and Alejandro Zaera-Polo of Foreign Office Architects in 1995 (and finally opened in 2002), the design still looks cutting-edge today, a prescient precursor to public projects like the New York High Line.1 On my pennultimate night in Japan, I sat out at the open air cafe on the terminal’s roof/walkway, witnessing a dizzying array of movement and activity in the redeveloped port. Behind me, to the south in the distant industrial port, the unloading and reloading of shipping containers progressed with mechanical grace. Nearby on the passenger terminal, a wedding ceremony reached its conclusion. With a cheer, the guests released an armada of pink and red balloons into the sunset sky above.

Yokohama’s International Passenger Terminal, Foreign Office Architects, 1995-2002.

The day I spent in Yokohama proved to be a fitting bridge to my next destination: Chile—a long, thin whisper of a country edged with 2,600 miles of coastline. Over the last six weeks of exploring Chile’s industrial heritage, I’ve spent much of my time in the country’s port cities. Life along Chile’s unending coast has formed a marked contrast to my inland adventures, which have taken me to remote pre-industrial German settlements, nitrate ghost towns, and copper mines; and the cosmopolitan, European-inflected metropolis of Santiago. This month, I will tackle the particular issues of Chilean port cities, investigating the heritage preservation and interpretive approaches being taken in three very different urban conditions—Valparaíso, Iquique, and the decentralized ports of the Chiloé archipelago. Next month, I’ll move inland to explore Chile’s historical and current mining landscape—company towns, worker housing, and the mines themselves.

Despite the strong sense of national unity that exists in Chile, the built landscape of its ports is surprisingly diverse. Indeed, Chile’s port architectures tend to be hyper-local, responding to geography, locally available materials, stored cultural knowledge, and the variable and uneven application of industrial technologies and practices. As interfaces between Chile’s powerful export economy and the rest of the industrializing world, the country’s historical port cities were (and still are) also particularly vulnerable to both internal and external economic shifts—such as the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, or the collapse of the nitrate economy in 1929. And although many port cities across the globe have served as stages for workers’ actions, including strikes and protests, this function seems outsized in Chile, particularly in the north where the harsh desert climate rendered port cities the default hubs for collective action.

The economic vulnerability of industrial ports in Chile and elsewhere in the world is registered in their architecture and urban planning. What I witnessed in South Africa and Japan was the almost universal redevelopment of port districts, a process that typically mingled adaptive reuse (see my second SAH Brooks blog post) and new construction. In Cape Town, that process included new luxury residential developments alongside trendy retail spaces, food halls, and landmark cultural attractions such as Zeitz MOCAA. In Japan, most of the port redevelopment seemed predominantly commercial, often incorporating elements of heritage tourism. And for most of the port cities I visited, the redevelopment process was already quite advanced, with some port cities now even needing to restore and refresh commercial architecture constructed in the 1980s.

The redevelopment of Hakodate’s “red brick warehouse district” dates to the 1988 opening of the Seikan Tunnel between Honshu and Hokkaido, which enabled Shinkansen (Bullet Train) travel to Hakodate. Capitalizing on this transit corridor, the historic warehouses were redeveloped as tourism-oriented commercial spaces.

The earliest commercial architecture along Kobe’s port appears to date from the mid-1980s. These slightly faded structures are joined by new additions, such as “Mosaic,” an ostentatious Florentine-themed labyrinth of indoor/outdoor retail space.

But while the cycle of redevelopment and re-redevelopment is already well underway in the postindustrial port cities of Japan, Chile’s entry into the cultural and heritage tourism game has been much more recent. While the end of the Pinochet dictatorship and Chile’s return to democracy in 1990 initiated an almost immediate upswing in nature and adventure tourism, the country is just starting to advertise its historical places, culinary offerings, and shopping opportunities. While few visitors come to Chile for the cultural element alone, heritage sites and experiences are becoming increasingly prominent supplements to adventure tourism standbys such as Patagonia or San Pedro de Atacama. As part of this new focus on heritage tourism, Chile is actively developing its historic port cities as cultural destinations, for both domestic and foreign tourists. Yet, owing the hyperlocality of their architectural traditions and their distinctive cultural and historical contexts, the heritage challenges faced in Valparaíso are unique from those in Arica, Antofagasta, or Lota—and the corresponding preservation and interpretation responses are equally as diverse.

Understanding heritage tourism in any given nation also entails decoding the various legal and economic vehicles through which buildings and landscapes are protected, preserved, and interpreted. In South Africa, a shared language and some fortuitous on-the-ground networking gained me access to helpful archives and a more direct path to decoding the intricacies of that country’s heritage sector. But in Japan and Chile, I’ve been battling a language barrier (a rather severe one in Japan) and a lack of contacts. In Chile, I’ve been combing the Chilean national monuments page, with some help from Google Translate. Local guides and walking tours have served as useful historical primers. UNESCO nominations and the accompanying maps have been uniquely helpful. I’ve cut a diet of Isabel Allende fiction and memoirs with the illustrative primary documents and incisive commentary contained in The Chilean Reader.2 In concert with the act of just being on the ground and observing how daily life functions in these historic places, this research yielded a much clearer conception of the motivating concepts behind how heritage is being conserved and developed for tourism in my three case study port cities.

Valparaíso: Patrimonial Zone and Piecemeal Preservation

In the nineteenth century, Valparaíso’s port functioned as an important resupply station for ships making the arduous trip around South America to reach the other side of the North American continent. With the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, Valparaíso fell into decline and depression. The sluggish economy prevented much from getting built, but also stopped much from getting demolished either. Encompassing a mind-bending topography of steep hills and valleys, Valparaíso’s historic urban core has retained much of its architectural integrity since the turn of the twentieth century. In 2003, Valparaíso’s historic downtown was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a move which has encouraged the gradual development of heritage tourism.

Valparaíso’s UNESCO-inscribed patrimonial zone and its buffer zone. Composite image created using satellite imagery from Google Earth and a map from the Consejo de Monumentos Nacionales de Chile (“Area Histórica de la Ciudad-Puerto de Valparaíso”).

- Muelle Prat

- Plaza Sotomayor

- Cerro Concepción

- Cerro Alegre

- Cerro Cordillera

- Cerro Santo Domingo

On my second day in Valparaíso, still groggy from my Santiago-Tokyo flight and the 12 hour time difference, I ambled down the terrifyingly steep hill of Cerro Alegre to partake in a walking tour of the historic urban core. While our guide, American ex-pat Johnny, tracked down a few stragglers, we waited on the ground floor of the nineteenth-century house he and his Chilean wife are in the process of restoring. The amount of work and money that had gone into the venture were clear from the care in the details. I knew, from seeing the crumbling, unrestored versions of Johnny’s row house further down the street, what those walls might have looked like before their restoration. It wasn’t pretty.

Valparaíso’s urban vernacular is typified by a unique fusion of local and industrial materials, and indigenous and European architecture, adapted to suit the demands of an intimidating topography. The most characteristic house type in historic Valparaíso arose in response to the city’s rapid growth at the end of the nineteenth century as an industrializing port. On a foundation of fired brick, a wooden frame, frequently in a half-timbered style, is filled packed earth adobe brick. Unlike the deep, load-bearing adobe of the Southwestern U.S. (or Northern Chile for that matter), this much thinner brick relies mostly on its wooden framing for support. The resulting structure is neither weatherproof nor rot-resistant, and so the exteriors are typically clad in corrugated tin, often brightly painted and featuring wooden trim in complementary colors.3

Above, a typical Valparaíso house with corrugated siding, painted in monochrome. Flowering plants like this bougainvillea are frequently used in the city to add color contrast and visual interest. Below, an example of street art on a house in the historic district. This mural is by a street artist who typically depicts scenes and people from southern Chile, frequently celebrating indigenous Mapuche culture. Also along this side wall, it is possible to see what Valparaíso’s characteristic corrugated tin looks like in its unpainted state, and what the uncovered adobe looks like as well (left of mural).

Once the walking tour was underway, John (husband) and I chatted with Johnny (tour guide) about his experience moving to Chile, and restoring this variety of historic house in a patrimonial district doubly protected by Chilean federal law and UNESCO status. The upshot? It’s a lot of paperwork. As Isabel Allende sardonically notes in My Invented Country, “The Chilean loves laws, the more complicated the better. Nothing fascinates us as much as red tape and multiple forms. When some minor negotiation seems simple, we immediately suspect that it’s illegal.”4 Indeed, the Kafkaesque complexity of the whole process runs counter to the city’s purported goals of stimulating investment in the historic district.

As we zigzagged through the patrimonial zone, I came to appreciate the extreme diversity of structures, landscapes, urban types encompassed by the 23.2 hectare inscription and its 44.5 hectare buffer zone. The UNESCO area extends from the area closest to the port up into the hills above. Home to Chile’s legislature, the thin ribbon of flat land nearest the water links a number of traditional squares and blocks planned on a relatively even grid. Plaza Sotomayor at the center is a testament to the city’s architectural diversity and to the evolution of preservation approaches employed within its urban zone. The Plaza opens onto the water, where an active port still serves the surrounding area and the inland capital of Santiago. But move just a few blocks inland and the tidy structure of linear parks and historicizing civic buildings falls away as the city dissolves into its characteristic hills with their twisting streets and tin-clad adobe houses. Into the tight fabric of hillside houses are woven significant historic buildings and landscapes that diverge from the adobe and tin vernacular—the Arts & Crafts Palacio Baburizza, a host of neoclassical mausoleums, and several neo-gothic churches. In addition to the buildings, historic funiculars form a layer of transportation infrastructure that eased the daily journey of port workers up and down Valparaíso’s precipitous hills.

The Consejo Nacional de La Cultura y Las Artes, a doctrinaire International Style municipal building, and a nineteenth-century neoclassical structure (after being put through the wringer of postmodern “preservation” tactics): just a sampling of the immense architectural diversity present in Plaza Sotomayor.

The extraordinary topography of Valparaíso required innovative infrastructure at the height of the city’s industrialization. As the city expanded, the issue of urban circulation also became more pressing and complicated. The workers who commuted from hilltop residences down to the docks and back each day faced a steep descent and correspondingly vigorous climb. A traditional streetcar would simply not function in these conditions, and so instead, the city created a series of urban funiculars to ease transit up and down the hills. At their height, there were about 30 funiculars operating in Valparaíso.5

Faced with the sheer diversity and complexity of the historic district’s architectural heritage, the city has pursued a preservation program that is decidedly piecemeal, pursuing isolated and intensive restoration projects, seemingly as catalysts to spur further private investment. On our walking tour, we climbed through the central public corridor of one of Valparaíso’s few fully restored hillside buildings. According to our guide, the government had spent millions (in USD) restoring this nineteenth-century complex, which is now being used as apartments. Just a hill away, though, were several adobes that were little more than crumbling ruins—structures that clearly needed to be razed for safety reasons. I suspect that the reason for focusing on construction rather than demolition has to do mostly with optics. On the ubiquitous infrastructure improvement signs throughout the country (“Todos para Chile!”), necessary removal is less glamorous than an entirely restored luxury apartment building.

The view from one of Vaparaiso’s fully restored building complexes, revealing a landscape where most historic buildings are in varying states of preservation and disrepair.

Similarly, rather than trying to resuscitate (or at least stabilize) all of the funiculars, the city has instead focused its efforts on a small handful. Out of the original 30, only 3 have been fully restored. The restored funiculars, which feature trendy kiosks with coffee and souvenirs, often attract queues of twenty minutes or more. Given that a ride costs only $100 CP (about 15 cents US), it’s hard to imagine that these extensive restorations are paying for themselves. Rather, the renovated funiculars and the isolated adaptive reuse projects seem targeted at changing the image of Valparaíso’s patrimonial zone—projects with substantial symbolic, if not economic, clout. But the city’s espoused desire for new investment has not been necessarily reflected in the experience of those looking to contribute, as with Johnny, who is fighting to save a historic building despite a lack of clear guidelines or municipal assistance.

A journey on Ascensor Reina Victoria, one of Valparaíso’s restored funiculars. Renovated funiculars like this one now attract mostly visitors, catering to that audience with coffee shops and souvenir stores in the cable houses. Locals seem to prefer the slightly grungier unrestored versions, probably because they’re not clogged by long lines of tourists.

The more successful restoration or reuse projects in the patrimonial zone are those that actively engage Valparaíso’s diverse community, rather than relying on optics or targeting wealthy residents and visitors to the exclusion of middle and working class citizens. One example is former Penitentiary Center of Valparaíso (used from 1843-1999; including to incarcerate political prisoners during the Pinochet regime) that through grassroots activism has been recycled into a community arts and education center. A thriving park adjacent to the arts building is one of the very few green spaces in urban Valparaíso, and creates a quadrangle with the brick ruins of a historic armory (1810) and another brand new museum and educational center. On the several occasions I visited the park, community members were out in force, walking dogs, picnicking, participating in a dance class, and selling art and baked goods from the shade of the community center.

Valparaíso Ex-Carcel (former prison reused as educational community space), 2011, architects: HLPS. The architects not only managed the reuse of the prison building, but also designed the new building constructed adjacent to it on the pentagonal site, which houses a larger lecture hall/auditorium.

As suggested by the prominence of the community art center, contemporary artistic practice is an integral part of the city’s identity. Indeed, Valparaíso’s unparalleled street art scene has become the predominant generator of tourism over the last ten years. With many street artists practicing in and around the historic district, the street art movement has at times butted heads with local preservation projects. In one instance, city planners were looking to restore a degraded public square to its turn-of-the-century state, a move that would have erased all of the street art within a certain radius. One mural in particular, a piece by an indigenous Mapuche artist from southern Chile, had grown to be a local favorite, for its political implications as well as its artistry. In the end, the stakeholders compromised, restoring some portions of the square while leaving the surrounding street art intact.6 Unlike the luxury apartment complex or the fully restored and heavily touristed funiculars, this dialogue between members of the community with different perspectives has resulted in a restored space that is both safer and more inclusive—bridging the gap between the historical meanings of the square and its current purpose. Paradoxically, it is the restoration projects in the patrimonial zone generated by and for the community that seem to be creating the most engagement and interest among foreign visitors. Remote foreign investment in boutique hotels might increase the overall level of amenities available in the area, but it seems that those who visit Valparaíso today are mostly attracted to the historic zone’s overall atmosphere—a robust synthesis of vernacular architecture, street art, natural topography, and the investment of committed locals like Johnny and his wife.

Three examples of street art engaging the past and present of Valparaíso’s architecture and urban condition. Prominent street artists are increasingly receiving lucrative commissions to paint municipal buildings and private businesses, but many street artists paint wherever there is available wall space in the historic district.

If local and touristic enthusiasm for Valparaíso’s street art could be more effectively harnessed in the historic district, there might be an opportunity for further mutually beneficial collaborations. Indeed, such a tactic holds promise for the sadly neglected industrial heritage that lies outside of the established patrimonial zone. Further north along the shore are scattered vestiges of Valparaíso’s early rail infrastructure, including a turntable with national monument status and several derelict but intact warehouses. Connected as they are to the current commuter rail, there seem to be opportunities here for creating more community-oriented educational spaces through adaptive reuse.

Despite its national monument status, this early twentieth-century train turntable in Valparaíso has been left as a virtual ruin next to the pristine new commuter rail that connects Valparaíso and neighboring urban areas to the north. How could such a ruin be changed through a combination of intelligent policy and grassroots activism to serve the larger community?

Despite its national monument status, this early twentieth-century train turntable in Valparaíso has been left as a virtual ruin next to the pristine new commuter rail that connects Valparaíso and neighboring urban areas to the north. How could such a ruin be changed through a combination of intelligent policy and grassroots activism to serve the larger community?

Chiloé: Decentralized Port Cities and Heritage Route

800 miles (1300 kilometers) south of Valparaíso lies the port city of Castro on the island of Chiloé. Castro is the political and symbolical capital of Chiloé, but is one of many small port towns across the main island and the archipelago of smaller isles off its east coast. Indeed, Chiloé’s economy seems largely decentralized—it would be fair to say that most of its cities function as ports to some extent. Like much of southern Chile, Chiloé remains relatively unindustrialized, due to geographic as well as historical and cultural reasons. When Charles Darwin visited in 1834, he discovered that even the native peoples, who had been living on the islands for many hundreds of years, could not penetrate the western reaches of the island, which covered in a dense arboreal ecosystem known as Tepaul.7 One of the last strongholds of the Mapuche people and a fierce holdout against Chilean independence, Chiloé has retained a distinctive cultural identity. During the late nineteenth century, Chiloé was Chile’s main producer of railroad ties, the demand for which was driven by the need to ship copper and nitrate industrially mined in other parts of the country. Castro, which had been founded in the late sixteenth century, was joined by a series of new towns born out of the railroad tie industry. A railroad connecting the major cities of Ancud and Castro was completed in 1912, which allowed access to the forests of the island’s interior.8

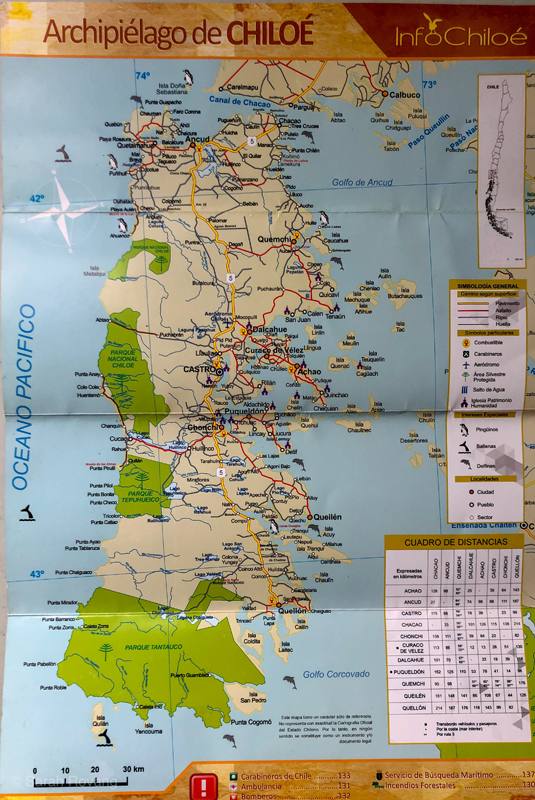

Tourist map of Chiloé, indicating the locations of all 16 UNESCO churches. In addition to the Ruta de las Iglesias, Chiloé also attracts substantial ecotourism in the form of lodges and farmstays. The private park (Parque Tantauco) that blankets the bottom quarter of the island is owned by the current president of Chile, billionaire Sebastián Piñera.

Despite its historical production of railroad ties, during my five days on Chiloé, I spotted very few signs of mass production or modern distribution systems. Yes, Coca-Cola has a distribution center there, and there is a large Lider grocery store (a chain owned by Wal-Mart) in Castro. But besides some of the shellfish farming that happens offshore in the waters of the inland sea, hardly any of the economic activity on Chiloé today (either production- or consumption-side) could be remotely classified as industrialized. Family fishing operations, small-scale animal husbandry, and potato farming seem to predominate. The persistence of traditional economic patterns is mirrored in the robust and multifarious wooden shingle architecture endemic to the island. While other parts of southern Chile also employ wooden shingle architecture, the shapes and colors on Chiloé are uniquely diverse.

Land with potato patch and pasture on Isla Lemuy. Below, my Instagram post showing a small sampling of the wooden shingle siding throughout Chiloé.

Instagram Caption: There are nearly as many shingle styles and colors on Chiloé as there are buildings. I have the feeling that shingle type has a deeper language to it than I could discern as an outsider. Is there some significance to the shapes, or is it purely personal preference? Maybe hyper-local tradition? Or just whatever the local carpenter had on hand? Regardless, they are a pretty spectacular vernacular ✨🏠✨ #sahbrooks #preindustrial #chiloe #carpentry #shinglehouse #vernaculararchitecture #chile

With the atmosphere of a pre-industrial idyll, Chiloé has become a locus for heritage tourism development in Southern Chile. Logging did not deplete the natural environment of Chiloé in the same drastic way as mining has in other parts of the country. There is a general sense that Chiloé is a place where traditional lifeways have been, for the most part, maintained. This is reflected in the island’s status as a “Globally Important Agriculture Heritage System,” a designation given in recognition of Chiloé’s intense and diverse potato agriculture.9 Fittingly, farmstays and ecolodges are readily available in the island’s more rural areas (“rural,” of course, being a relative term on Chiloé). There has been a resurgence of traditional Chiloé cuisine as well, particularly curanto, a stew of potatoes and shellfish that historically was cooked in underground pits.

While not cooked in the traditional pit, I can vouch that the curanto at Carlita’s lunch counter in Dalcahue is a very satisfying repast. In case one forgets where the bulk of the ingredients come from, the food hall takes the form of an inverted boat, using ship carpentry as structural inspiration in much the same way as Chiloé’s iconic UNESCO churches.

But the main attraction of Chiloé centers around its 16 UNESCO churches, which are arrayed across the eastern portion of the archipelago. The initial churches were established in the seventeenth century as part of the Jesuit order’s “Circular Mission,” and combined indigenous building traditions, particularly pertaining to shipbuilding and wood carpentry, with the European ecclesiastic architectural traditions that the Jesuits brought with them. In the coming centuries, the Franciscan order continued this mission work, and added another level of architectural richness to the mestizo Chilota tradition. Critically, Chiloé’s churches are still maintained as devotional centers of their communities.10

These three UNESCO churches, all located on the main island of Chiloé and within an hour’s drive of each other, testify to the breadth of architectural expression within the Chilota School. Above, the Church of Colo, dating from around 1890, represents one of the earlier Jesuit models, with a less elaborated, unpainted facade and a long, simple basilican plan. In the middle, the Church of Tenaún shows an example of a slightly larger church with a more complex plan, accentuated by corrugated cladding and painted decoration. And below, the Church of San Francisco (1910-1912) Castro is a highly developed Franciscan example of the Chilota School, featuring extensive buttressing on the exterior, multiple chapels on the interior, and groin vaulting in various native woods. In contrast to most of the other Chilota School churches, Castro’s is distinctly neo-Gothic in style. Almost all of the churches have been rebuilt multiple times over the years since the first arrival of the Jesuits in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

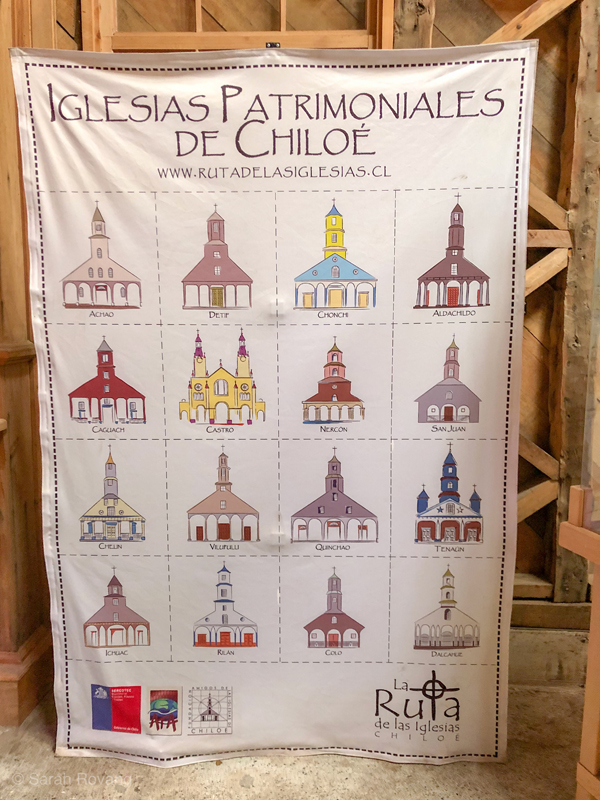

The main interpretive center for the churches is in Ancud, the northernmost major city on the island and the port of entry for most visitors. The interpretive center itself is in a wooden church of the Chilota School, which makes it a particularly effective venue for learning about the traditional carpentry techniques that go into these buildings. There are intricate scale models of all the churches, rendered in wood and painted to match their full-scale brethren. Images of the 16 church facades arrayed as a four by four grid are everywhere: on posters, calendars, and even carved into wood panels by local artisans as souvenirs. The implicit message of the interpretive center and these depictions is that the enterprising heritage visitor should try to see all 16 churches while on Chiloé.

An interior shot of Centro de Visitantes Inmaculada Concepción in Ancud, the main interpretive center of the 16 UNESCO churches, and an impressive example of the Chilota School in its own right. Below, the ubiquitous 4x4 grid of church facades that shows the range of architectural expression across the UNESCO listing.

Accordingly, the churches have been linked into a heritage route, for which there is ample signage. The roads are consistently well maintained and mostly paved. While a few of the churches are remote even by Chilote standards, most of them are accessible with a rental car and a willingness to undertake a bit of driving and a few short ferry rides. Over the course of three days, I managed to see 12 of the churches. But the act of driving to all of those distant churches, was, to be entirely trite, more about the journey than the destination. On the drive from Castro to the tip of Isla Lemuy, an island with two of the UNESCO churches, the overall architectural heritage and landscape are just as much of an attraction, though one not codified in the official Ruta de las Iglesias. In the charming town of Curaco de Veléz, Chilote shingle style reaches its apotheosis, as evidenced by the sheer number of shapes and shades on every street. The lime-green A-frame Chilota church (definitely not UNESCO) adds a mid-century flare to the main plaza, and the catacomb of a Chilean independence hero at the plaza’s center contributes just the right amount of morbid fascination. Along the town’s tidal zone is a brand new walkway, complete with plenty of ornithological interpretation (Chiloé is the southern terminus of many bird migration patterns). These are all architectural experiences that I would have missed without the impetus of the Ruta de las Iglesias.

Architectural and natural attractions in Curaco de Veléz, a port town that while lacking a UNESCO church of its own, lies along the Ruta de las Iglesias.

Even Castro itself, which has become a kind of launch point for many visitors’ explorations of Chile, has seen a corresponding surge in other preservation activities outside of those directly linked to the churches. Castro’s distinctive palafitos, the traditional wooden houses on stilts that line the city’s tidal waterfronts, have been given new life as restaurants and boutique hotels. Today, Castro’s palafito streets are becoming walking tour and cultural tourism hotspots. As with many places I’ve visited during my Brooks travels, I found that in Castro, heritage tourism begets more preservation activism and even more demand for well-preserved heritage places. In my view, the palafito craze can’t be separated from the success of the Ruta de las Iglesias.

A row of palafitos to the south of downtown Castro. The distinctive stilted houses have been largely converted into restaurants and boutique hotels, benefitting from and reinforcing the system of heritage tourism already in place through the Ruta de las Iglesias.

Because the Chilote archipelago never fully industrialized, it has been saved the pain of de-industrialization and the corresponding population drain and economic decline. Tourism is not the sole lifeblood of this place—it is merely another sideline, running parallel to more traditional economic strategies. Against the background of gradually increasing heritage tourism, life on Chiloé goes on as it has for many years, now with the benefit of paved roads.

Iquique: Cultural Corridor as Singular Heritage Focus

In 1821, Europe became aware of a unique reserve of naturally-occurring nitrates were found in the Atacama Desert.11 Then part of Peru, this coveted economic resource sparked a war between Chile, Peru, and Bolivia (the War of the Pacific, also called the Saltpeter War, 1879-84). Ultimately, Chile prevailed, and in doing so, gained the nitrate-rich deserts to the east and north of Iquique. The Chilean nitrate industry not only enriched the national coffers and facilitated the country’s entry into an industrialized world order, it also transformed explosives manufacture and global agriculture in the early stages of industrialized farming. While nitrate mining (the architecture of which I’ll tackle in next month’s post) exacted extreme human and environmental costs on the Atacama Desert, the resulting fertilizer was presented to the rest of the world as “white gold,” a substance that could renew soil and nurture abundant crops.

Along Chile’s northern coast, port cities and towns sprung up to funnel that “white gold” from the network of railway-connected nitrate mines, or salitreras. Mine owners, mostly North American and English, built mansions, restaurants, offices, and casinos in these towns, finding beachside living preferable to the extreme heat of the Pampa (or high desert). Lacking suitable local building materials for such structures, the administrators imported what they needed, often from great distances. The historic district of Iquique—one of the largest and longest-lived of the northern port communities—was constructed from Oregon pine. In addition to building materials, the mine owners brought techniques and styles well established in the United States and Europe. As a result, most of the wooden buildings in the oldest part of Iquique are balloon-framed, with facades in a Georgian, neoclassical, or Adams style. The other main uniting architectural feature is the provision of shade through the use of porches, verandas, and covered rooftop areas. 12

Inspired by artist Ed Ruscha’s 1966 Every Building on the Sunset Strip, I undertook the (slightly less ambitious) process of photographing every building on either side of Baquedano Street. The above image is a small sample from the project illustrating the characteristic nineteenth-century architecture of this historic corridor.

Although Iquique has a sizable historic district, the majority of redevelopment and preservation has been focused on Baquedano Street, the primary corridor where mine managers and owners built their mansions, running south from Arturo Prat Plaza down to the beach. Baquedano Street has been on Chile’s UNESCO tentative list since 1998, but progress on the nomination has stalled. While I can only speculate as to why this nomination hasn’t moved forward, I would guess that it has something to do with the fact that the city, without permission or approval from the National Monuments Council, has undertaken several major development projects on the Baquedano. Some of these projects, such as the construction of an underground parking garage under Arturo Plat Plaza could (justly) be seen to compromise the historical integrity of the urban fabric.13

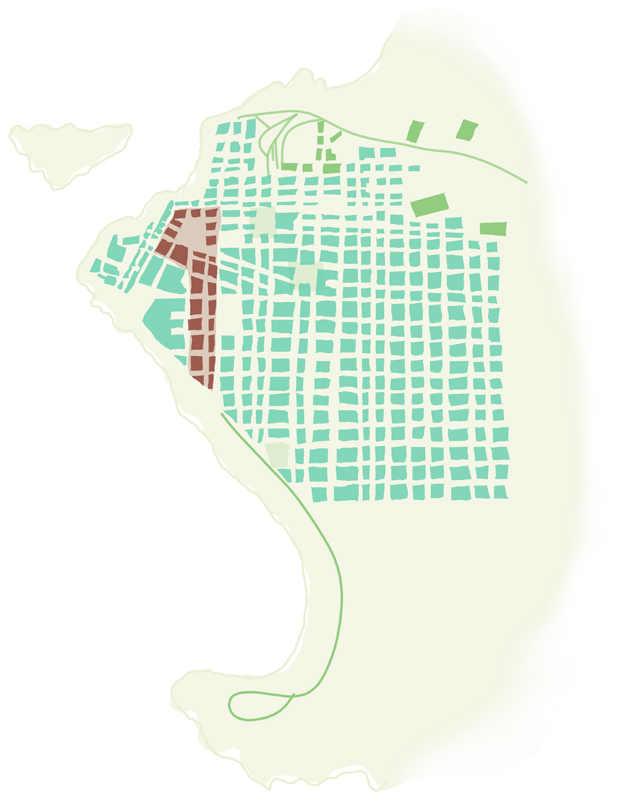

A diagrammatic map of Iquique based on a 1907 map from Iquique’s regional museum. Baquedano Street and Arturo Prat Plaza have been highlighted in red, while other historic places and infrastructure from this period are highlighted in green. While the buildings directly affronting Baquedano have been relatively well preserved, many of the buildings marked in green seem to receive less funding for preservation and upkeep, and have not been successfully integrated into the city’s heritage tourism.

Although there is reason to be suspicious of the preservation tactics being deployed on Baquedano, the pedestrianized street slowly seems to be developing into an active cultural corridor, in which somewhere between a third and half of its buildings are currently occupied by tour companies, hostels, local museums, restaurants, schools, or mine company offices (old habits die hard). During my daily walks to Arturo Prat Plaza, I watched the incremental progress of a restoration project on Iquique’s 1889 Teatro Municipal. Over the course of my stay, the scaffolding slowly came down, revealing a freshly painted and restored neoclassical facade in white and pastel blue. Concerts and festivals on Baquedano are frequent, as are pop-ups for various causes, from electronics recycling to human rights awareness. A regular collection of street vendors hawks their wares on the northern end of the street, and a historic diesel-powered streetcar chugs along leisurely from one end of the street to the other, adding more historic charm than reliable transit. Well-trafficked enough to feel safe and kept meticulously clean, the street seems on the verge of becoming the tourism and community hub local planners intended.

The newly restored Teatro Municipal (1889) and a temporary stage on Arturo Prat Plaza. Exploring the cultural corridor mid-morning reveals the extensive daily labor required to keep the street and plaza looking pristine.

The strength of Iquique’s corridor approach is that it focuses limited resources and creates a contiguous architectural heritage experience. Despite the addition of the underground parking garage, the historic feeling of the street remains, accentuated by a few exemplary buildings, such as the 1904 Casino Espanol and Palacio Astoreca (now the city’s cultural center, built circa late nineteenth century). However, outside the Baquedano Street corridor, there are a number of significant buildings from the nitrate era that have gone largely neglected. Near the end of my visit I met Marco, a Peruvian geologist and longtime resident of northern Chile, who has observed the changes in Iquique and the surrounding landscape over the past several decades. Marco reported that when he first came to Iquique, the whole downtown historic district had the grandeur and historical integrity of Baquedano Street. Over the last decades, however, the historic integrity of downtown has been radically compromised, and many of the original wooden buildings have been lost, due to new development and natural disaster. Unlike Valparaíso’s patrimonial zone, the area surrounding Baquedano Street has witnessed the construction of several high rise apartment buildings, along with a new commercial area with several grocery and department stores. The other threat to the area seems to be natural disaster, and fire in particular. Located in a city with an average rainfall of 1 mm a year, all of that Oregon pine architecture is a virtual tinderbox. After more than a week of wondering whether any of the wood buildings near my (thankfully concrete, high rise) AirBnB were fireproof, one morning I watched, horrified, as several houses a few blocks away ignited and virtually burned to the ground in the minutes it took the fire department to arrive.

The opulent Casino Espanol (1904), above, is still operated as a restaurant and meeting area by the Spanish Club of Iquique. Below, the late nineteenth-century Palacio Astoreca (now used as the city’s Cultural Center), is a prime example of wooden Georgian architecture on Baquedano street, with its airy wrap-around porches.

A fire several blocks from my lodging in downtown Iquique, which burned several homes. First responders arrived quickly, but the structures were essentially incinerated within the intervening minutes.

Additionally, there is little interpretation or mention of many of the important historic buildings that do remain off of Baquedano Street. Without some concerted digging on the Chilean National Monuments website, I would not have found any of them as the majority don’t appear on tourist maps of the area. No wonder—currently heritage tourism is not what draws most visitors to Iquique. Today, the city serves primarily as a launch point to venture out into the nearby Atacama Desert or to sandboard and paraglide down the city’s towering dunes. In town, there’s a small (though well-done and comprehensive) regional history museum, and a life-sized recreation of the Chilean warship Esmerelda available to tour with an advance reservation. But significant national monuments are hidden in plain sight, including those that have been reused to serve civic functions, such as the railway administration station, which now has become a municipal family services building.

Wanting to experience the heritage tourism that is on offer, I ventured down to the Muelle Pasajero, the city’s 1901 passenger quay (and a National Monument). Here, a charmingly informal boat tour company runs a “heritage” tour. For about $6 US, the rider can participate in an hourlong tour that covers Iquique’s still very active port, a colony of sleepy sea lions, and a buoy marking the spot where a Chilean warship (the Esmerelda) sank during the War of the Pacific.

Iquique’s railway station and railway administration building (both c. 1879) are both critical components of the city's industrial heritage, but their location several blocks from Baquedano means that few visitors are aware of their presence.

Baquedano Street has the potential to help build engagement with these other important and significant architectural remnants of Iquique’s early years as a nitrate port. Rather than being the sole heritage attraction in Iquique, Baquedano Street could spur more preservation efforts throughout the city. Though Baquedano Street may have been the main corridor on which the wealth of nitrate mining was made manifest as architecture, the influx of that wealth was made possible by the railroad station, the old industrial port (still in use as a containerized port), and the passenger quay (1901). Further, the 1907 Iquique Massacre, an event in which the army systematically killed approximately 2,000 striking mine workers and their families, is not an event that is memorialized on Baquedano Street. This was perhaps the most significant historical event to occur in Iquique in the twentieth century, and while there is mention of the event in the regional history museum, the main memorial is in a municipal cemetery largely inaccessible to visitors. As I wrote about a few months back, interpreting industrial heritage as a landscape rather than as a sequence of isolated and unrelated sites would benefit cities like Iquique, uniting all of these distinct buildings into a coherent visitor experience.

Surprisingly, the best interpretation and memorial space dedicated to the 1907 Iquique Massacre is located at the former nitrate mining town of Humberstone, a 45-minute drive east of Iquique. While Iquique’s regional museum devotes a series of interpretive panels to the event, the massacre is without a major memorial in downtown Iquique.

Conclusion: A Question of Relevance

The success of Chiloé’s heritage route approach seems to be as much about interpretation and marketing as it does about the architecture itself. I would wager that only a niche set of visitors are passionate about Jesuit-Mapuche wooden ecclesiastical architecture before going to Chiloé, but the topic is presented in an approachable and welcoming way at the main interpretive center, and mainstream tourism sites such as Lonely Planet have seized on the ready Instagramability of the 16 churches. The churches serve as an entry point into the expanded built landscape of Chiloé. Chiloé’s core strategy of using existing momentum and enthusiasm to create a positive feedback loop around heritage tourism seems promising in both Valparaíso and Iquique as well.

Valparaíso’s current attraction for most tourists is the street art that fills its streets and adds vibrancy to its patrimonial zone. How could interpretation of contemporary street art more directly engage with the city’s industrial past? Numerous artists operating in the city engage with historical themes in their art—this might be leveraged to raise awareness of ongoing preservation struggles throughout the patrimonial zone. In Iquique, Baquedano Street should capitalize on its remaining architectural integrity to become the hub, rather than the exclusive focus, of architectural preservation and interpretation.

On my last night in Iquique, I had dinner at El Wagon, a restaurant several blocks off Baquedano devoted to resurrecting and preserving the historical working class foodways of Chile’s Tarapaca Region. The walls were decorated with old photos of pampino workers from the salitreras, old kerosene lanterns, and posters advertising Chilean nitrate in a variety of languages. I tried the sopa de pan y cebolla (bread and onion soup), a dish that was historically prepared by pampina women during the mining strikes—this was food for lean times designed to stretch all available ingredients. The complete sensory experience of consuming this historic dish surrounded by the material culture of the nitrate era was far and away the most effective and meaningful heritage experience I had while in Iquique.

This experience drove home to me that more than clever marketing is needed for these historic port architecture efforts to succeed. Part of the other reason that Chiloé’s Ruta de las Iglesias works so well is that it illuminates the relevance of history to the present. These churches are not just idiosyncratic architectural artifacts, but places where present-day community is formed and enacted through the living practice of the Catholic faith. That tangible connection between past and present, similar to what I experienced through food at El Wagon, is what makes this heritage route so poignant and effective as a visitor experience. At the end of the day, ports aren’t interesting solely because of what they were a century ago, but what they still are today—fragile ecosystems contingent on the whims of global capitalism. When Chile’s copper reserve runs out in a few decades or becomes economically inefficient to mine (as some experts predict), what will happen to its ports? What if a new globalized system of shipping eventually supplants today’s shipping containers? With these questions in mind, heritage interpretation becomes not just a way to mediate the past, but to meditate on the future.

- For more, see David Langdon, “AD Classics: Yokohama International Passenger Terminal / Foreign Office Architects (FOA) AD Classics: Yokohama International Passenger Terminal / Foreign Office Architects (FOA),” ArchDaily, October 17, 2018, https://www.archdaily.com/554132/ad-classics-yokohama-international-passenger-terminal-foreign-office-architects-foa. ↩︎

- Elizabeth Q. Hutchison, Thomas M. Klubock, Nara B. Milanich, and Peter Winn, The Chile Reader: History, Culture, Politics (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015). ↩︎

- “Historic Quarter of the Seaport City of Valparaíso,” UNESCO/WHC, inscription 2003, accessed December 30, 2018, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/959 ↩︎

- Isabel Allende, My Invented Country, Kindle Edition, 2004: 91. ↩︎

- These devices are also called “elevators,” though out of the thirty or so original funiculars, only one of them is a true vertical elevator. The rest transverse the hillsides at a steep incline. “Elevators of Valparaíso,” World Monuments Fund, accessed December 30, 2018, https://www.wmf.org/project/elevators-valpara%C3%ADso ↩︎

- Information from Valpo Street Art Tours, http://www.valpostreetart.com ↩︎

- See Charles Darwin, The Voyage of the Beagle, Chapter 13: Chiloé and Chonos Islands, 290-302. Accessible at https://www.coolgalapagos.com/Darwin_voyage_beagle/darwin_beagle_chapter_13.php ↩︎

- Information panel at the Regional Museum of Ancud in Ancud, Chile. ↩︎

- “Chiloé Agriculture,” GIAHS (Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems), Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, accessed December 30, 2018, http://www.fao.org/giahs/giahsaroundtheworld/designated-sites/latin-america-and-the-caribbean/chiloe-agriculture/en/ ↩︎

- UNESCO World Heritage Site, “Churches of Chiloé,” https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/971; accessed December 26, 2018. ↩︎

- Roberto Hernandez, “El Salitre (Nitrate), Historical Resume since its Discovery and Exploitation,” excerpt from the 1930 book, accessed December 30, 2018, http://www.albumdesierto.cl/ingles/2histori.htm ↩︎

- Consejo de Monumentos Nacionales de Chile, “Calle Baquedano,” accessed December 30, 2018, http://www.monumentos.cl/patrimonio-mundial/lista-tentativa/calle-baquedano ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top