-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Not another Greek Tragedy

Aymar Marino-Maza is the 2018 recipient of the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship. All photographs are by the author, except where otherwise specified.

Odeon of Herodes Atticus, amphitheater at the base of the Acropolis, Athens

For an architect, language has always been a beautifully malleable thing, filled with words to be used, abused, made up, or entirely redefined. Architecture theorists use language the way architects use building material. The architecture theorist strives to be more than a technical expert, but also a philosopher or an art critic. As a result, architectural writing has sampled—sometimes willy-nilly—from other fields and has kept a safe distance from that boring reality of the lived experience of space. The consequence is that architectural writing has for too long been able to confound its readers and get away with it.

In architecture, we rarely have to worry about something like the inappropriate use of the words “culture” or “religion.” This is not the case in a field such as anthropology, where every word that is not a preposition or an article needs thorough explanation. What’s more, in anthropology, there seems to exist a universal guilt over methodology, as ethnographic field notes are held up against such things as flow charts and graphs and, my least favorite, excel sheets. The architectural writer has never had to submit to a standard methodology for conducting research nor to a critical development of language—because neither exists. And some people might consider that a problem…

In the next twelve texts, the curious and free-spirited architecture will be confronted with its cautious and experienced neighbor, anthropology. Together, they will tackle a topic that might bring them together like a pair of love-blind newlyweds, and then send them crashing apart when confronted with such things as differing politics, complicated histories, and opposing lifestyles. Hopefully, though, we’ll be able to glean something of consequence before architecture finds itself a new mistress.

In a way, this methodological marriage will mirror the very topic being discussed: the way that displaced people integrate with host communities. Architectural space will serve as a platform upon which these scenes of interaction develop and will be analyzed alongside the actors.

It’s a wonder that architecture hasn’t used the ethnographic model more often, considering how significant the way people inhabit space should be for an architect. After all, architecture is space designed for habitation. I hear a chorus of groans from across college campuses as professors read those words. And yet, though we may—nay, should—have many definitions of architecture, this one should not be disregarded because some accessory-wearing starchitect deems it unworthy of the coveted capital A. To this end, let us get these two crazy kids hitched, and let’s see if we can’t gain a little insight into the way displaced people actually inhabit space.

We begin in Greece, where national identity and human movements have played an intricate game of cat and mouse, forever at each other’s heels, from the migrations of the first millennium BC to the most recent caravan to reach its Mediterranean coast.

Panorama of Athens

A woman sitting in the plane lifts her forefinger, middle finger, and thumb to her forehead, to her chest, and to her lips, repeating the act in swift successive movements. A man in his motorcycle takes a sharp turn and, straightening out, lifts a hand to his forehead, to his chest, and to his lips. A group of children runs out of a house, backpacks bounding behind them, and from within the doorframe, a woman’s fingers come up to meet her forehead, her chest, and her lips.

This is a quintessential Greek image, one that any visitor will see repeated over and over across the country. Like an abbreviated sign of the cross, it seems to mark the beginning and the end of any voyage. An image that is similarly typical is the kandilakia. Kandilakias are roadside shrines in the shape of miniature chapels that dot the Greek landscape from Xanthi to Heraklion. They commemorate both those lives lost to the road and those who were lucky enough to survive it.

Just as every town has a church, it seems that every bend in the road has a shrine. Erected by the families of those lost souls, these shrines are a symbol of a deep sense of spirituality and a responsibility toward preserving and celebrating a person’s life. And to the foreigner, they are a physical reminder of the strong spiritual and cultural links that tie the Greek people together.

A selection of photographs of kandilakia from across Greece.

The reason these symbolic images are so quintessentially Greek is because the Greek identity is intimately tied to a shared understanding of religion and ancestry. It’s no accident that the Panhellenic (pan meaning “all” and hellenic meaning “Greek”) games that marked the rise of the Greek city states were held in religious sanctuaries such as Olympia and Delphi. For this reason, it is impossible to speak about displaced people within Greece without speaking about these aspects of the Greek identity: religion and ancestry.

Greece, which, seen on a map appears as disintegrated as the USSR, is in fact a nation whose many individual islands share an indelible Greek-ness. This is especially interesting when considering the history of the country, which saw these islands broken up, abandoned, fought over, colonized, re-colonized, over and over throughout the years. But even in Ancient Greece there was a sharp distinction between those who were Greek and those who were not. It is not surprising when noting that the word xenophobia comes from the Ancient Greek words ξένος (xenos), meaning foreign, and φόβος (phobos), meaning fear. More specifically, though, the Ancient Greeks termed barbarian (which comes from “barbed Aryan,” which funnily enough means “bearded noble,” for anyone interested) those who did not speak the Greek language. Greek-ness was therefore on a certain level a linguistic distinction—interesting, as language is something that can be learned, and therefore a characteristic which, unlike color or race, can be acquired. One could hypothetically become Greek by learning to speak Greek. There are obviously more shades to this definition, layers of cultural heritage and shared beliefs, but the message is clear: to consider yourself Greek, you must first understand the Greek way and express yourself in the Greek manner.

A selection of photographs of Kandilakia from across Greece.

One of the interesting aspects of studying the history of displacement, and also one of the most frustrating, is that there never seems to be a good place to begin telling the story. It is impossible to define a single original people against which migrants can be studied. The analysis seems to always have a variable constant, as the displaced ultimately place themselves and a new displaced replace them. And Greece is no exception. Actually, due to its location in the Mediterranean, it is a prime example of how variable this constant can be.

Pelasgians, the people that inhabited the Aegean region before its Hellenization by the Greeks in 12th century BC, the people that were the supposedly indigenous to the area, are named pelasgi, as referring to “the sea.” And, as some sources cite, were migrants themselves, as their name also denotes, linked as it is to the word pelargo or “stork.” Ancient Greek religion, for example, came out of a mixture of Pelasgi and the incoming Greeks, just as the changing foundation of Classical Greek art is a product of the increased contact with Egypt and the Far East in the 7th century BC. Many of the images and myths—such as the palm leaf, the siren, and the griffin—depicted in Classical Greek art are eastern motifs assimilated into the Greek repertoire, both aesthetic and spiritual.1 All this is to say that even in the very first definitions of Greek-ness there is an ever-present cross-pollination, leading one to wonder if Greece can truly be defined without referencing all the people, cultures, and customs that it has had contact with.

These are people that not only interacted with Greece, but were colonized by Greece, were themselves colonizers of Greece, were incorporated into Greek cities, or were kicked out of them. All of the spaces that will be discussed in this text incorporate a mixture of these different forms of interactions and a layering of these different people.

A great place to start is with the monastery. At first sight, one might not think to speak of a monastery when discussing displacement. But then again, the definition of displacement has for too long been grossly limited to describing the destitute and the weak. This is not the definition that will be used in these texts. In the paragraphs that follow, the displaced people will range from monks to lepers, from soldiers to anarchists, and through their differences, they will all speak to the one true element that unifies them, having had to leave one’s home.

A selection of views of Meteora monasteries.

As early as the 9th century AD, a group of hermit monks began to occupy the cliffs of Meteora, hiding in hollows along the lowest mountain ranges. For some incomprehensible reason, they decided it was a good idea to exchange caves for buildings, and began to build monasteries at the pinnacles of these mountains. These fortification-like spaces were built in a way that the only way to reach them was if the monks lowered stairs, ropes, or nets to grant access.

The inaccessibility of these monasteries was originally intended to separate the hermits for meditative and spiritual reasons. Yet, these fortifications quickly served a second purpose. In the 14th century, this solitude was threatened by the increased attacks of Turks against the Ottoman Empire, who themselves had allowed the Orthodox to remain intact when they invaded the region in 1386. During the Turkish occupation that followed, the monasteries served as refuge for the people persecuted by the Turks. These spaces served both as safeguard for the inhabitants, but also their faith. The few buildings that still remain stand proudly as symbols of a people unwilling to give up faith—and yes, there is a double entendre there.

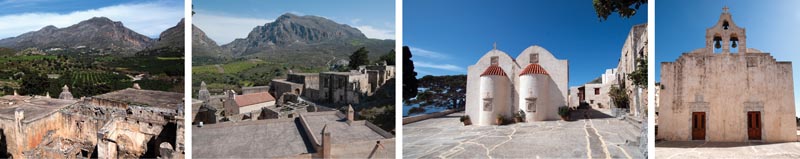

(left) Lower Monastery, Preveli, Crete; (center right) Rear Monastery courtyard; (right) Church Façade, Rear Monastery, Preveli, Crete.

In the sleepy coast of south-western Crete, hidden behind the winding roads of its mountainous central spine, on a sun-drenched hill overlooking the ocean, is the Preveli Monastery. This peaceful scene is actually the setting of one of the most inspiring examples of the Cretan revolutionary spirit. For those who do not know, Crete has a long and complex history of resisting invasion, a disease to which the island is unhealthily prone. The largest of the Greek islands, it has seen empires come and go, from the mighty Minoans, considered to be the first European civilization, to the Mycenaean Greeks, the Romans, the Iberian Muslims, the Venetians, the Ottomans, the British, and to top it all off, those pesky Germans. But throughout it all, the Cretans have managed to maintain a fiercely independent identity.

Like many across Crete, the monks at Preveli rebelled against each of the armies that invaded the island. The monastery served on multiple occasions and against multiple enemies as an outpost for rebel forces, a haven for religious refugees, a storehouse for supplying resistance, and a final point of rescue for those who escaped off the island. More accessible than Meteora, Preveli experienced the backlash of this resistance and its Lower Monastery and fields were burned down on numerous occasions.

Driving up the quiet hill to the complex, it is easy to miss the ruins of the Lower Monastery, tucked away under a bend in the road and fenced off from visitors. One can pass it almost unwittingly, stopping instead at the monument that stands at the entrance of the Rear Monastery. This monument commemorates the courageous acts of those who resisted invasions and fought for freedom. Here, as in Meteora, the space of displacement isn’t shelter-less or helpless. Instead, it is a space of resistance, of unyielding belief, fraternity, and hope. So, removing the guns and violence, it doesn’t seem a bad model to follow.

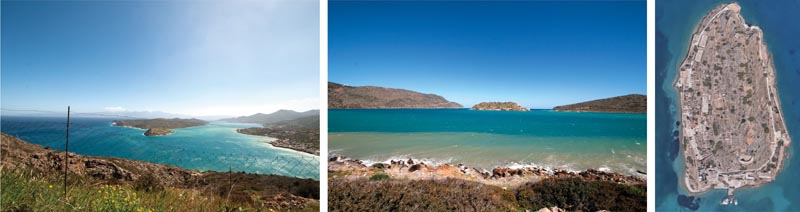

(left & center) Spinalonga Bay with Kalydon island, Crete; (right) Google Map aerial of Kalydon

A few hours from Preveli and just a five-minute boat ride from the northern coast is the island of Kalydon, commonly referred to as Spinalonga. Originally connected to the Cretan mainland, this marooned fortress was carved apart from the main island during the Venetian occupation, intended as a defensive measure against pirate and Turkish attacks on the ancient port of Olous. This severing of the umbilical cord allowed the island to survive the many attacks on the motherland that it was originally built to protect.

The island was so well designed as a defensive structure that it could have been the poster child for “nations barely hanging on.” While the rest of Crete fell under Ottoman rule in the 17th century, the island remained under Venetian control and functioned as a refuge for Christians until 1725. In an ironic twist of fate, the island later became a refuge for Ottoman families after the Cretan revolt of 1878, when the Ottoman Empire surrendered the island to the Christian Cretans.

From 1913 until 1957, the island was used as a leper colony. Born, a man who lived on the island at the time and recounted his story to the BBC, stated that until 1930 the inhabitants of the colony “sought solitude to escape the face of the other.”2 This statement is grounding for those of us who have not been exposed to such a socially handicapping illness. On a certain level, many of us have experienced this sensation of dread at seeing our own pain reflected in our fellow man. And yet, as these people demonstrated, this dread can be turned on its heel: in 1930, a new movement led by the Brotherhood of the Sick sparked a sort of urban renewal on the island and a new sense of community amongst these secluded people. A commercial street developed, community gatherings such as concerts started to be held in public spaces, and part of the medieval fortress was torn down, breathing some much needed sea breeze into the lives of these people.

It is possible to study the experience of this group of people as occupying an oft-forgotten form of displacement: displacement due to illness or handicap. And yet, this very specific form of displacement carries many of the same basic implications that one sees in displacements due to war or famine. For example, once a person was taken into a leprosarium, he or she was typically disrobed of citizenship, unable to marry or even handle local currency. This state of citizenship limbo and the camp as a form of quarantine are elements that inevitably affect displaced people on social and emotional levels. The small-scale intervention that was executed within this almost “controlled conditions” urban space can serve as a case study of how to begin to infuse normality and a sense of home into even the most inhospitable habitat.

A selection of photographs of abandoned buildings across Greece.

Something that will surprise no one is the sheer amount of ruins there are in Greece. But what is actually surprising is that most of these ruins are not ancient monuments; they are simply abandoned buildings. They are the 19th and 20th century architecture that has fallen into disrepair, due in part to the recession and the bursting of the housing bubble, but also to the Nazi occupation, to the civil war, and to a history of urban planning measures that have left many urban spaces buried in layers of red tape. These buildings are not only in large cities like Athens and Thessaloniki, but also small villages and picturesque tourist sites.

A selection of photographs of abandoned buildings across Greece.

It just so happens that in one of these urban ruins something magical and definitely a bit illegal happened. In 2016, City Plaza, an abandoned hotel in the anarchist (verging on gentrified) Athenian neighborhood of Exarcheia was taken over by a group of activists and transformed into a refugee shelter. Sustained without government funding, the hotel runs as a form of commune-meets-shelter typology. The space is somewhere between a squatter’s den and an urban Eden.

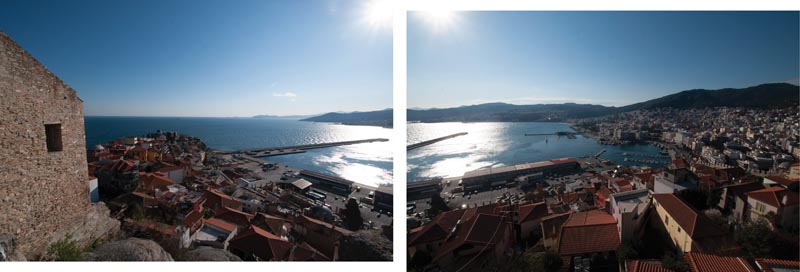

(left) Thessaloniki; (center) Eastern Orthodox Church and Greek Refugees Monument; (right) Eastern Orthodox Church façade, Thessaloniki.

A very different image can be seen in a city like Thessaloniki, a major port in North-Eastern Greece and a hub for incoming refugees from Turkey, Syria, Iran, and Iraq, among others. As many countries around it have closed their borders to refugees, Greece is in an impossible position of being the lone doorman to the flood of unexpected visitors. Cities like Thessaloniki have had to bear the brunt of the weight. The entrances to the city’s police stations have become the unlikely base for many of these refugees, who have camped out there in the hope of processing their asylum applications, which they achieve, ironically, by getting arrested. Surrounded by a sea of abandoned buildings, the displaced here is in a state of urban limbo, but this time in full view of the public.

Thessaloniki is nicknamed the “Refugee Capital,” but not because of this current situation. It refers to an earlier one, which came about after the Greco-Turkish War, when the two nations implemented a population exchange, essentially swapping out Orthodox Turks for Muslim Greeks in what feels like a super inappropriate game of Rummy. This decision stemmed from the strong sense of religious identity that defined both Greece and Turkey at the time, and is an example of the use of a millet system, wherein religious groups were considered akin to nations, given certain forms of autonomy within a country and certain forms of legal protection. The exchange was intended as a way of stamping out the persecution that was being committed against Orthodox citizens in Turkey, many of whom were ethnically Greek. After the influx of these forcibly displaced people, Thessaloniki experienced a new and uncontrolled urban growth, which marks the city up to this day.

Panorama of Kavala with a view of the Imaret.

The effects of the 1923 population exchange weren’t felt only within Thessaloniki. Kavala, a smaller city a few kilometers to north, tells a different story. The ethnic Greek refugees were originally housed in the city’s imaret, the Ottoman poor house built in the city by Mohammed Ali in 1821. The imaret, now a hotel, remains a symbol of the Muslim culture in the region, while the steep, winding streets that serve as its backdrop are a clear depiction of east meeting west, with such architectural elements as sachnisi (a bay window with wooden beams) and bagdati (a Baghdad wattle-and-daub technique) embedded into the predominantly Macedonian architecture.

But what’s truly remarkable isn’t the architecture; it’s the way history books describe the influx of the refugees from Asia Minor. Here, the migrants aren’t described as a burden but are said to have contributed to the newfound prosperity of the city, both agriculturally and industrially. Though it is easy to be contented by this idyllic clean-cut depiction, readers should remember that the story of displacement is never so very clean. In truth, the population exchange, much like the overall relationship between Turkey and Greece throughout the years, was little if not strained.3 It is a story, like all those that have been told up until now, of violence, confusion, and a whole lot of human error.

This story will be described with more of the detail it deserves in a few months, when a text on Turkey comes out. Until then, let us simply end with this idealized image, of people helping people, of rebels fighting for freedom, of lepers making themselves at home, and of a Greece that can never be explained in such a short piece of writing.

1 Department of Greek and Roman Art. “Greek Art in the Archaic Period.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/argk/hd_argk.htm (October 2003)

2 Warkentin, Elizabeth. "Travel - The Abandoned Greek Island Shrouded in Mystery." BBC. September 22, 2017. Accessed March 30, 2019. http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20170921-the-abandoned-greek-island-shrouded-in-mystery.

3 Cooper, Belinda. "Trading Places." The New York Times (New York), September 16, 2016.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top