-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Mexico City: From Mexica Past to Modernism and Beyond

Cinco de Mayo is not Mexican Independence Day.

Since I am addressing a forum of intellectuals with a keen interest in history and culture, many of you might already know this fact. I might have heard it a time or two in life, only to forget, and then be reminded again in Mexico City. I am not ashamed to admit that. Why is this tidbit of information important to the history of architecture and urbanism in Mexico City, you ask? It has everything to do with memory of place, transnational dialogues, regional differences, and most immediately, place names.

Place names

My first week in Mexico City I went to the heart of it all, Zócalo, and walked many miles exploring the city, getting a feel for its historic center. I was surprised to find that one of its major arteries, one that embraces Zócalo on the western periphery was named 16 de Septiembre. While studying a map of Centro Histórico the significance street placement was apparent, but the meaning was lost on me, until I began a minor investigation into the significance of the date. Modern Mexico City place names are reflective of its long, eclectic, troubled, and triumphant past, embracing a mixture of indigenous, independence, and revolutionary figures. Alameda Central, for instance, is cradled by streets named for Miguel Hidalgo and Benito Juárez, meant to pay homage to historic figures of independence and reform. Delving into the meaning behind the names of a place is often one of the most enlightening activities one can pursue. Each name is consequential and is a snapshot of the past. In a capital city, place names are the epitome of patriotism, nation building, and myth making, a la Roland Barthes.

Figure 1. View of Alameda Central from Torre Latinoamericano

Pre-Hispanic past in contemporary city

In this capital city there are urban and architectural achievements that, by virtue of design, harken back to the pre-Hispanic Mexican past. The Zócalo, historic center of the city, is a nodal point from which all understanding of the orientation and layout of the city can be derived. This is because the Aztecs founded their ancient city of Tenochtitlán in the same space now occupied by the grand plaza, national palace, and cathedral. When the Spanish conquered the great city, they admired its aqueducts and engineering. They chose to build their outpost in New Spain on what remained of the Aztec achievements (after, of course, they burned and ravaged the city first). As scholar Jacqueline Holler argues in her article “Conquered Spaces, Colonial Skirmishes: Spatial Contestation in Sixteenth-Century Mexico City,” part of the power of the Spanish conquest was the fact that the Spaniards effectively cannibalized the space and materials of the Aztec city:

The revision of Tenochtitlan as a colonial capital, moreover, was an attempt to usurp rather than deny indigenous sovereignty. This usurpation demanded physical change on a grand scale, rather than intellectual sleight of hand. The dismantling of an indigenous urban complex and its reassembly in an altered form were the products of tremendous indigenous labor, itself an object lesson in domination.

Also in the historic center are the ruins of Templo Mayor just east of the Metropolitan Cathedral, as well as the Palacio Nacional erected on the ruins of Moctezuma’s “New Houses.” In the historic center the Mexica and Spanish colonial pasts sit in complex juxtaposition to each other, illustrating clearly the significance of the space layered with history.

Figure 2. View of Metropolitan Cathedral over ruins of Templo Mayor

European Influences

Mexico City felt more European to me than I imagined it would. I had tried desperately to figure out why this was the case. What qualities of the city gave me this feeling? One of the most outstanding qualities I would argue is the vitality of life in the public sphere. The city has an embarrassment of riches in regards to the proliferation of public parks within its boundaries. The city has taken a renewed interest and invested in its public spaces recently. From the grand public parks of national significance like Alameda Central to the small pocket plazas and gardens in the various neighborhoods like Jardín Pushkin and Parque las Americas, residents of Mexico City pass much of their free time in the presence of others, beneath the shade of los árboles en las parques. Mexico City is green, but not in the trendy way we talk about “being green” today (although it has begun countless initiatives to reduce the impact of pollution in the city). The tree canopy is noteworthy, and lessens the blinding quality of light on a sunny day. Two of the most recent places I have lived battle the problem of a disappearing or deficient tree canopy – Washington, D.C., and New Orleans. The incessant heat and humidity in those cities during the summer months make living in both places nearly unbearable. Walking the streets of Mexico City this June I have thought about how the quality of life in places like Washington and New Orleans would be improved tremendously with a far-reaching and widespread tree canopy. Granted, New Orleans has its live oaks on major thoroughfares, but these prized trees are not evenly dispersed throughout the city.

Figure 3. Images of daily life in parks taken within the span of a few hours on one day. Clockwise from top left: Plaza Morelia, Parque México, El Foro Lindbergh in Parque México, Parque España, Jardín Pushkin, and Plaza Río de Janeiro

Revolution and social reform

Politics. Passion. Poisonous liaisons. Perseverance.

These are issues I was confronted with during the week I dedicated to touring sites associated with Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Leon Trotsky. The way those messages are intertwined in the art produced in the middle of the twentieth century in Mexico City is raw, emotional, and nuanced. The artwork of Kahlo and Rivera, as well as their friendship with Trotsky during his last days in Mexico continue to define post-revolution politics for scholars across various disciplines. Kahlo’s brand of feminism, Trotsky’s appeal to a sympathetic Socialist Mexico, Rivera’s many interpretations of Mexican history and warnings about the pro-capitalist future are topics accessible to scholars who are intrigued by intersectionality. The spaces in which conversations took place among these three, some of Mexico’s most celebrated and discussed historic figures, continue to be pilgrimage sites today.

Figure 4. Interior views of Casa Azul, Trotsky’s House, Diego Rivera’s Studio, and Anahuacalli Museum

Struggle, revolution, and social reform are major themes in Mexican history, and world history at large, and that narrative was evident at the Tlatelolco site. I was advised to visit this site by Leslie Moody Castro, an art curator who works between Texas and Mexico. I had no idea what to expect, I just knew I had to go. Aztec ruins? Student protests? A massacre? The Olympics? I was confused and intrigued at the same time.

I started my journey at Tlatelolco walking from the bus station through the housing complex designed by architect Mario Pani. I eventually found my way to the university and museums. What the Tlatelolco site lacks in cohesiveness it makes up for in content. The Centro Cultural Universitario Tlatelolco runs the museum section of the site, and the four various exhibits that are on display in the center are disjointed in their relationship to each other and are counterintuitive in circulation patterns. None of that matters, however, once you enter into the space itself.

Figure 5. Conjunto Urbano Nonoalco Tlatelolco

The first place I visited was the Museo del Tlatelolco, which told the story of the pre-Hispanic city that existed just north of, but separate from, Technotitlán. The exhibit space was so well curated that it would appeal to children and adults alike. There were numerous moments for multi-media activity to engage visitors, and the exhibit productions and displays were thoughtful and tasteful. After being thoroughly wowed by the Museo del Tlatelolco I visited the Colección Stavenhagen, which hosted a beautiful array of pre-Hispanic objects, from the everyday to the highly sacred. I finished my visit at the utterly poignant Memorial del 68, a space that provided opportunity to reflect on the student protests of 1968 in Mexico, and the terrible massacre that happened shortly before the opening games of the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City.

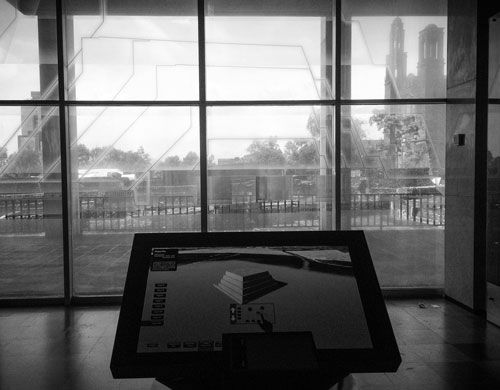

Figure 6. Looking out onto Aztec ruins of Tlatelolco from inside the museum. Temple of Santiago Tlatelolco seen on right. A stark contrast of indigenous and colonial constructions

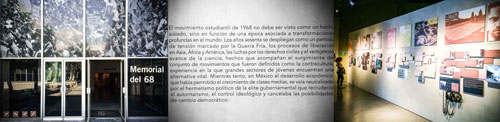

The Memorial del 68 situated the Mexico City student movement within an international trend of revolution and reform in the 1960s. The opening video, “El laboratoria de la libertad,” is a montage of popular culture – music and imagery – of the world that captures the spirit of the 1960s. It is followed by a timeline that illustrates major shifts in social and cultural politics. It ends in a quiet, dark space of reflection where images of the plaza and events of 1968 are reproduced in an abstract, haunting manner. In all, this museum is a moving encapsulation of a moment in Mexican history that changed its trajectory in a profound way. Tlatelolco from the pre-Hispanic city, the site of Spanish conquest, the housing complex, the student massacre, and the ramifications of the 1985 earthquake, is a often-overlooked (by tourists) space in the city that truly captures the long history of the region.

Figure 7. Memorial del 68

Preservation and interpretation

Besides Tlatelolco, two of the most noteworthy places I visited in the Mexico City metropolitan area were Teotihuacan and the “Arquitectura en México 1900-2010” exhibit. Perhaps I found them notable because of their success in preservation and interpretation. I use the word success carefully, (some would argue loosely) since I am very aware that conservative preservationists consider Teotihuacan a Disneyfication of Mexican history. I measure the success of both the historic site and the exhibit in two different ways.

Teotihuacan is an architectural historian's delight and disappointment. The delight comes from one’s ability to get swallowed up in the overwhelming scale of structures that make up the Ciudadela, Avenue of the Dead, Palace of Quetzalpapalotl, the Pyramid of the Sun and the Pyramid of the Moon. The disappointment would afflict any preservation and conservation purist. Most of what one sees today at the site has been reconstructed, and historical evidence proves now that earlier reconstructions, done in haste by Leopoldo Batres for the Centenario, were incorrect. UNESCO takes a fairly judicious stance about this condition, noting:

While some of the earlier reconstruction work, dating from the early years of the last century, is questionable in contemporary terms, it may be considered to have a historicity of its own now. In general terms, it can be said that the condition of authenticity of the expressions of the Outstanding Universal Values of Teotihuacan, which can be found in its urban layout, monuments and art, has been preserved until today.2

Scholar Gillian Newell does a very thorough job of describing the way various groups – local, national, international, tourist and indigenous alike – create a culture of consumption that support identity-formation at Teotihuacan. Her article, “Rhyming Culture, Heritage, and Identity: The ‘Total Site’ of Teotihuacan, Mexico,” takes into account the different motivations people have for visiting the site, and argues that we must understand all of these various meanings and practices, both historical and contemporary, to grasp the “total site” of Teotihuacan. I would agree with her conclusion.

Figure 8. Teotihuacan selfie

The highly acclaimed “Arquitectura en México 1900-2010. La construcción de la modernidad. Obras, diseño, arte y pensamiento” exhibit deserves all the praise it has received in the international press. Situated in the Palacio de Cultura Banamex - Palacio de Iturbide, this far-reaching show is divided into easily digestible themes that illustrate the evolving country’s architectural ambitions, from the Porfirian era to the twenty-first century. The exhibit took advantage of the spacious site, with a beautiful array of models, furniture, architectural drawings, paintings, sculpture, and video. The exhibit was even more successful than the “official” museum of architecture in Mexico, the Museo Nacional de Arquitectura. Poorly organized because of space constraints, the lonely national museum of architecture sits in the top floor of the Palacio de Bellas Artes, and is hardly visited by a soul (its blog is worth a visit).

Figure 9. Arquitectura en México exhibit

One the one hand, Teotihuacan is successful because it remains open to interpretation. Little is known about its original residents. The spirituality of the space, however, speaks to the masses. It is a sample of pre-Hispanic Mexico that various people derive meaning from, and it is also part of a larger lore about pyramids, outer space, and extraterrestrials. Indeed, there is something for everyone, even the “believers,” so the meaning of what it is to be “authentic” is drowned out in the voices that proclaim the site to be both authentic and universal.

On the other hand, the “Arquitectura en México 1900-2010” exhibit is successful because it does exactly what the site of Teotihuacan does not. It is directive, illustrating how political and social ideologies informed various periods of growth and design in Mexico. Whether highlighting Porfirian elite design, or modernization efforts in anticipation of the 1968 Olympics, the textual information and visual aids of the exhibit create an enlightening experience for visitors.

Mexico City present and future

Mexico City’s past – Mexica, Spanish colonial, Porfirian, revolutionary – and the reclamation of and tension between these identities are at the forefront of how Mexico interprets and understands itself. There is no consensus on what it means to be Mexican, as far as I can tell, and like any major country the interpretations vary by region, vocation, place of origin. I don’t know how these various identities affect the current state of affairs in the city and nation. One thing is for sure – Mexico City does not try to hide any of it. At least not anymore.

As I ended my time in Mexico City and arrived in the Yucatán, I tried to find the words to sum up the major takeaways from spending a month in this capital city, this global city. In many ways, the national presence is felt so very strongly, with the richness of the heritage of the country at one’s fingertips. In other ways, the city’s position on the global radar is also poignant, as I have had the opportunity to meet people from the States, Argentina, France, Spain, and other countries during my time here.

The Mexican past is as long and complicated as a Diego Rivera mural, and in the twenty-first century, it includes narratives about hope and disillusionment that move beyond the time frame represented in the famous murals in the Palacio Nacional. It has been over 60 years since that piece was finished, and the story of the city is far from complete. Mexico City’s standing and trajectory for the twenty-first century is an enigma for someone new to the city, such as myself. Clearly it is a thriving global city, one that has unparalleled human capital in population alone, and additionally has a wealth of foreign trade and investment. The Brookings Institution noted in 2010:

Over 20 million people live in the Metropolitan Area of Mexico City (MAMC), making in the largest urban agglomeration in the Western Hemisphere, the largest Spanish-speaking metro globally, and the third largest metropolitan area in the world. Mexico City’s GDP stood at $411.4 billion in 2012, making it the eighth largest urban economy in the world.3

These factors are clear to anyone who has spent time in the city recently. The Brookings Institution warns, however that despite creating a place for itself in the international economy, “Mexico City’s international stature is not as stable and its global brand not yet as recognizable as other prominent emerging market cities like Istanbul, Mumbai, Shanghai, and São Paulo.”4

While in Mexico City I was introduced to two organizations that represent the future of Mexico City’s cultural politics and help us understand the country in new and profound ways. The missions of the organizations are quite different. Their strengths are that they are headed by young people – in their 20s and 30s – and depend on a serious understanding of the social, political, and cultural state of Mexico. The first organization, ArtraversARTE, is a contemporary art tourism company that “weave[s] in historical context, cultural perspective, and urban life to create an unforgettable experience” of the city.5 Atravesar means “to cross over, to break through, to pierce.” AtraversARTE was created to provide art professionals and aficionados an opportunity to have transnational dialogue about the state of contemporary art in Mexico, with an eye on the future. Since the art is deeply embedded within the genius loci, the urban condition is part and parcel of what one takes away from their AtraversARTE experience. I was very much impressed with the organization’s mission, and it reminded me of another organization, Afrikanation Artists Organization, that works to promote cultural exchange between America and Africa – particularly east Africa: Somalia and Ethiopia.

The second organization I learned about in while in Mexico City is TECHO, an NGO that depends on “the collaborative work of families living in extreme poverty with youth volunteers … [to] overcome poverty in slums.”6 The TECHO mission is the epitome of what it means “to build:” edificar. The Spanish translation of the word is closer to its true meaning and essence, its Latin roots: aedificium (building) + facio (make). TECHO consists of political advocates who believe in the art of building, not just in the physical sense, but also in framing, constructing, and providing a foundation for an idea that all people should live without poverty. Their work spans Latin America and the United States.

Despite the fact that Mexico City is one of the largest and most populous cities in the world, so many aspects of the city remain part of the quotidian, time-tested local traditions. I started this blog talking about place names. I will end doing the same. On my penultimate day in Mexico City I made a trip to the El Museo de la Ciudad de México for personal and professional reasons. Personally, I wanted an official body representing the city to tell me exactly what it wanted me to come away with on my trip. Professionally, I’ve done research on city museums in Washington, D.C. and London and wanted to see how Mexico City approached this concept. I arrived at the museum and was about to pay my money for a ticket when the woman at the counter said, “You are here for an exhibit about Mexico City? We don’t do that any more.” I was flustered, checked to make sure I was in the right place, and then walked out. A guard who saw me walk up asked me why I was leaving.

Me: Esté es El Museo de la Ciudad de México, pero... no es el museo de la ciudad de México?

Guard: Sí.

Me: Por qué no cambia el nombre?

Guard: La gente lo conoce como "El Museo de la Ciudad de México."

Esto es la belleza de lo cotidiano.

Figure 10. El Museo de la Ciudad de México

H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship Google Map

Learn more about the H. Allen Brooks Travelling Fellowship

Recommended reading:

Enrique X. de Anda Alanís, “The Preservation of Historic Architecture and the Beliefs of the Modern Movement in Mexico: 1914–1963,” Future Anterior: Journal of Historic Preservation, History, Theory, and Criticism 6 no. 2 (Winter 2009): 58-73

Luis Castañeda, “Beyond Tlatelolco: Design, Media, and Politics at Mexico ’68, Grey Room (Summer 2010) 40: 100-126

Keith L. Eggener, “Juan O'Gorman versus the International Style: An Unpublished Submission to the JSAH,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 68 no. 3 (September 2009): 301-307

Keith L. Eggener “Placing Resistance: A Critique of Critical Regionalism” Journal of Architectural Education 55 no. 4 (May, 2002): 228-237

George F. Flaherty, "Uncanny Tlatelolco, Uncomfortable Juxtapositions,” Defying Stability: Artistic Processes in Mexico, 1952-1967, ed. Rita Eder (Mexico: MUAC, 2014), 400-417

José Villagrán García, Jorge Otero-Pailos and Ingrid Olivo, “Architecture and Monument Restoration (1967),” Future Anterior: Journal of Historic Preservation, History, Theory, and Criticism 6 no. 2 (Winter 2009): 88-103

Jorge Tárrago Mingo, “Preserving Rivera and Kahlo: Photography and

Reconstruction,” Future Anterior: Journal of Historic Preservation, History, Theory, and Criticism 6 no. 1 (Summer 2009): 50-67

Jacqueline Holler, “Conquered Spaces, Colonial Skirmishes: Spatial Contestation in Sixteenth-Century Mexico City,” Radical History Review no. 99 (Fall 2007): 107-120

Kathryn E. O'Rourke, “Guardians of Their Own Health: Tuberculosis, Rationalism, and Reform in Modern Mexico,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 71 no. 1 (March 2012): 60-77

Kathryn E. O'Rourke, “Mies and Bacardi: Mixing Modernism,” Journal of Architectural Education 66 no. 1 (2012): 57-71

Susie S. Porter, “‘And That It Is Custom Makes It Law:’ Class Conflict and Gender Ideology in the Public Sphere, Mexico City, 1880-1910,” Social Science History 24 no. 1 (Spring 2000) 111-148

Mauricio Tenorio Trillo, “1910 Mexico City: Space and Nation in the City of the Centenario,” Journal of Latin American Studies, 28 no. 1 (February 1996): 75-104

Steven S. Volka, “Frida Kahlo Remaps the Nation,” Social Identities: Journal for the Study of Race, Nation and Culture 6 no. 2 (2000): 165-188

Adriana Zavala, “Mexico City in Juan O’Gorman’s Imagination,” Hispanic Research Journal 8, no. 5 (December 2007): 491–506

[1] Jacqueline Holler, “Conquered Spaces, Colonial Skirmishes: Spatial Contestation in Sixteenth-Century Mexico City,” Radical History Review no. 99 (Fall 2007): 107

[2] UNESCO, “Pre-Hispanic City of Teotihuacan,” http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/414-title=Pre-Hispanic

[3] Brookings Institution, “The 10 Traits of Globally Fluent Metro Areas: Mexico City,” Global Cities Initiative, a Joint Project of Brookings and JPMorgan

[4] Ibid.

[5] Tanya Diaz, “AtravesARTE Brings Experiential Travel to Mexico City’s Contemporary Art World,” AtravesARTE Launch Press Release April 2, 2014.

[6] TECHO, “What is TECHO/History,” http://www.techo.org/paises/us/techo/what-is-techohistory/

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top