-

Membership

Membership

Anyone with an interest in the history of the built environment is welcome to join the Society of Architectural Historians -

Conferences

Conferences

SAH Annual International Conferences bring members together for scholarly exchange and networking -

Publications

Publications

Through print and digital publications, SAH documents the history of the built environment and disseminates scholarship -

Programs

Programs

SAH promotes meaningful engagement with the history of the built environment through its programs -

Jobs & Opportunities

Jobs & Opportunities

SAH provides resources, fellowships, and grants to help further your career and professional life -

Support

Support

We invite you to support the educational mission of SAH by making a gift, becoming a member, or volunteering -

About

About

SAH promotes the study, interpretation, and conservation of the built environment worldwide for the benefit of all

Antigua: La vida de las ruinas

“The most weirdly beautiful ruins in the world are found amid the jungles of Guatemala.”

- Edgar Lee Hewett, Head of the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Southern California, qtd. in Ransome Sutton, “What’s New in Science: Weirdly Beautiful Ruins,” Los Angeles Times November 26, 1933: G19

“Do not smile at the degraded vestiges of a past civilization that we meet in Central America. They are living tombs of a wrecked national intelligence which has succumbed to the rapacity and worse proclivities of relentless and unmerciful conquerors.”

- Ferd C. Valentine, U.S. Surgeon – Urologist, “People and Places in Guatemala,” Manhattan 1 no. 6 (June 1883): 424

- Edgar Lee Hewett, Head of the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Southern California, qtd. in Ransome Sutton, “What’s New in Science: Weirdly Beautiful Ruins,” Los Angeles Times November 26, 1933: G19

“Do not smile at the degraded vestiges of a past civilization that we meet in Central America. They are living tombs of a wrecked national intelligence which has succumbed to the rapacity and worse proclivities of relentless and unmerciful conquerors.”

- Ferd C. Valentine, U.S. Surgeon – Urologist, “People and Places in Guatemala,” Manhattan 1 no. 6 (June 1883): 424

There is life among ruins. Antigua is the perfect place for a case study on preservation – the methods of conservation, local governance, and international partnerships. There is much to be learned from this small Central American city, designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979.

As the above quotes indicate, there is also an abundance of mystery in the crumbling edifices for those who delight in “ruin porn” à la Detroit post-industrial decline or post-Katrina New Orleans. Art critics often point to the long history of deriving aesthetic pleasure from gazing upon remnants of a bygone era. There is an irony or depravity, however, in appreciating the vestiges of a colonial past (this is true of the post-industrial and post-disaster pasts as well, for different yet occasionally parallel reasons). The colonial past is marked with oppression, forced assimilation, and denial of indigenous rights, belief systems, and customs.

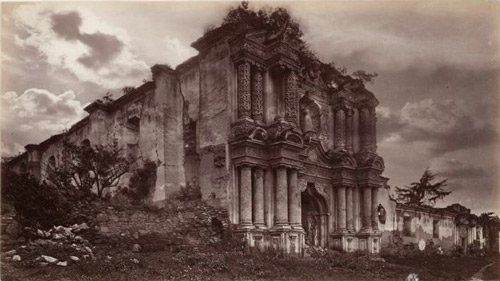

[Figure 1. View of the church of El Carmen after 1874 earthquake, Antigua 1875. Eadweard Muybridge. Canadian Centre for Architecture.]

[Figure 2. El Carmen Market and Ruins 2014.]

Antigua has been a destination for wanderlusts and adventurers since the late 19th century. Even photographers Eadweard Muybridge and Arnold Genthe documented the collapsed structures of the former capital of the Kingdom of Guatemala in 1875 and sometime between 1899 and 1926, respectively. The overall tone of the earliest North American accounts of Antigua that I found in the pages of publications such as the Manhattan and Outing, an Illustrated Monthly Magazine of Recreation is one of wonder and intoxication with the ruins, and condescension to the large Mayan population that even today resides in pueblos on the periphery of the city.[1]

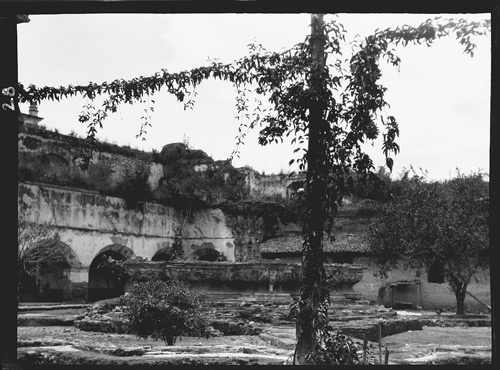

[Figure 3. Cloister of La Merced monastery, between 1899 and 1926. Arnold Genthe. Library of Congress.]

[Figure 4. Cloister of La Merced before a wedding 2014.]

Hernán Cortés assigned Spanish conquistador Pedro de Alvarado the task of “conquering and settling” the Kingdom of Guatemala in 1523. This kingdom included parts of modern-day Belize, Chiapas (southern Mexico), Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. The first capital of the Kingdom of Guatemala was founded in 1524 at the indigenous Cakchiquel Maya city of Iximché, however, the Cakchiquel resisted Spanish domination, and the Spaniards relocated their capital in 1527 to the vicinity of present-day Ciudad Vieja on the side of Volcán de Agua. The second capital site suffered losses due to a major landslide in 1541, and in 1543 the Spaniards moved further down into the Panchoy Valley and established the third site for the Muy Leal y Muy Noble Ciudad de Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala, or the "Very Loyal and Very Noble City of Saint James of the Knights of Guatemala," now known as Antigua. Here the capital remained and flourished through countless earthquakes until 1773, when the Santa Marta earthquake leveled the city. The earthquake of 1773 led to the relocation the capital once again in 1776, this time to its current location 45 km northeast, now known as Guatemala City. Residents of Antigua were reluctant to abandon their city, and some remained despite efforts by the Spanish colonial government to force them to the new location.

Antigua Today

“Mention Antigua, Guatemala, to those who have been there and you'll probably end up mesmerized as they rave about its churches, volcanoes, restaurants, and cobblestone streets. Mention Antigua to those who return to its splendor year after year and you'll no doubt be brought into their world of enchantment as they describe learning a new language, coming to appreciate a different culture, and expanding from one's comfort zone in the perfect place to volunteer.”[2]

Modern Antigua and its environs survive through a mixed economy of coffee production, tourism attributed to the proliferation of Spanish schools and its ruins, and its popularity as a destination-wedding site. I often heard employees at museums, cultural sites, stores, and even the police respond to my queries and thanks with “Estamos aquí para servirle,” which may be a common response in the country, but was one that I thought might be tied to the tourism/service industry. There is also a sizable expat population, a topic that then-anthropology doctoral candidate Joshua Levy covered in his dissertation at the University of California, Berkeley. “Expats are walking contradictions,” Levy stated, “stumbling down the cobblestone streets of a hometown that has always been for foreigners.”[3]

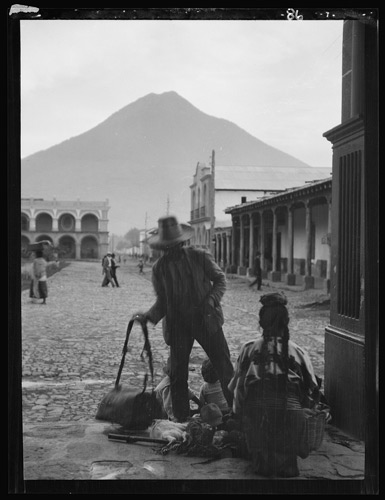

There is a seemingly understood wealth disparity between the urban and rural (mainly indigenous) populations. Many of the indigenous people come to Antigua to sell their wares then travel back home. There are countless non-profits attached to Antiguan business that have created a relationship with the indigenous population in the vicinity – anything from a restaurant to a yoga studio to a Spanish school in Antigua will probably have a volunteer program located in a nearby pueblo.

While in Antigua I visited Niños de Guatemala, a well-run NGO in Ciudad Vieja, Guatemala. They offer primary education to the poorest segments of children in Ciudad Vieja. These are children who live in close proximity to livestock – roosters, mules, etc. They probably don’t have running water or electricity. Most of their homes – constructed of discarded materials – have dirt floors. I was on the tour entitled “Experience Guatemala.” I met people who were volunteering for weeks at a time to support the mission of the organization. I learned so much – so much in fact, that my heart was broken.

[Figure 5. Worst section of housing in Ciudad Vieja. Some Niños de Guatemala students come from this neighborhood.]

In Antigua it seems that volunteering as a tourist is the norm. In fact, it is a stark contrast to my time in Mexico where tourism was all about relaxation and pampering the guest (at least in the Yucatán). Another North American visiting Antigua asked me in a rather relaxed conversation, “So are you here to volunteer?” It was an innocent enough question. “No, I’m here to study architecture.” My answer didn’t feel sufficient in this context. It felt like vanity. For the first time this trip I felt that in order to legitimize my presence I should physically contribute to the larger community in some way. All the English language magazines like Qué Pasa and Revue include a significant amount of information about non-profits and NGOs operating in the country. Even what one would consider a more traditional cultural tour, like the outstanding ones offered by Elizabeth Bell at Antigua Tours includes information about how your money helps sustain the culture and heritage of the town in very beneficial ways.

Preservation and the Realities of the Everyday

By the time of the 1773 disaster numerous religious orders such as Franciscans, Dominicans, and Mercedarians had already created their respective convent and church complexes, and a number of educational institutions were established in the city as well. The remnants of those religious institutions are the backbone of the architectural tourism industry in Antigua. If you tire of visiting churches and convents on an architectural tour, then Antigua is probably not the place for you. What is particularly gratifying about this collection of sites, however, is the fact that they represent a very unique version of Spanish baroque known as “earthquake squat.” Additionally, each site is treated in a manner specific to its condition and current use. You might ask, “What use does the site of an architectural ruin have today?” The main cathedral of Antigua, San Jose Cathedral, is still very much a working religious institution, as are the churches of San Francisco and La Merced. Iglesia Beatas de Belen on the southeast edge of the city operates both as a church and as a school. The convent of Santo Domingo has been converted to a boutique hotel, and includes in its expansive grounds two art galleries, several museums, and archaeological sites such as the crypts. These architectural sites juggle being both functioning structures and ruined playgrounds for locals and tourists alike.

[Figure 6. Nave of Santo Domingo set for a wedding.]

Alternatively, the church and convent of Santa Clara is no longer a functioning religious institution, but is a much visited tourist destination. Sites like Santa Clara, Las Capuchinas, and San Francisco offer some interpretation for the visitor, while others such as San Jerónimo and La Recolección offer little to none. What the latter locations offer instead is the space for magic and imagination. The allure of the unknown and place to create your own story. These sites act as public parks for locals, places for lovers to cuddle under trees, and for family explorations.

[Figure 7. Is it architectural vanity? Selfie with immense La Recolección ruins in the background.]

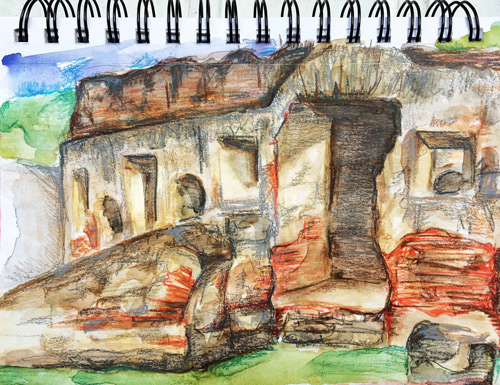

For instance, my time at La Recolección was spent dancing my gaze along the jagged edges of the ruins, not necessarily trying to make sense of what I was seeing. My artist heart rejoiced in the chaos. I wanted very much to sit, draw, and paint, but the heat told me to keep moving. I did have the opportunity to sit and indulge in the ruins of Las Capuchinas. I spent most of my time trying to depict the materiality, the mixture, and the mess of the tower for the novices (a fascinating complex). My dreamy watercolor impression seems most accurate to me. I feel that I should have left my depiction one of an impression rather than trying so hard to put in the details with Prismacolors. As an academic, it is difficult to interpret and validate my impressions. As an artist, it felt “right.”

[Figure 8. Las Capuchinas Pt. 1: Water color.]

[Figure 9. Las Capuchinas Pt. 2: Water color plus Prismacolor.]

So how does one begin to understand the interworking of these preservation decisions that highlight certain structures and leave others to serve only as romantic backdrops to the action of their visitors? I searched to find contemporary research that addressed these issues. I found one master’s thesis on La Recolección written in the last ten years.[4] Elizabeth Bell regularly publishes short yet concise articles about the heritage preservation of Antigua in local publications.[5] Websites that cover contemporary architecture trends lacked any information on Antigua (part of this is due, of course, to strict regulations against new building in the city). The bulk of detailed original architectural research on the city was conducted in the 1950s and 1960s.

A Few Unanswered Questions

Why is Antigua an overlooked subject in preservation case studies? There seems to be a great wealth to discuss regarding seismic activity and building for earthquakes and volcanoes/mountains with the threat of edifice collapse?

The city was inscribed in the World Heritage List in 1979 – at a high point of international attention to the Guatemalan Civil War. Was the inscription of the city somehow related to this humanitarian crisis and the understood danger to the culture and built environment of Guatemala?

Who studies Guatemalan culture, both the built environment and intangible heritage? While in Yucatán, Mexico, I found archaeologists took up the charge of studying Mayan life and ruins in the region. Guatemala seems to fall under the purview of geographers and anthropologists – why the dearth of architectural historians/preservationists and related literature?

Is the lack of study a result of the civil war?

What happens when we privilege the narrative of the colonial past over the indigenous past and present? Are the Cakchiquel natives benefiting from the preservation of these romantic ruins?

Finally, do architecture and preservation as professional fields have a social responsibility?

We often find our most endangered sites and cultural landscapes in regions that have suffered from disinvestment, natural disaster, and war. We, as architectural historians, preservationists, architects, conservationists, historians, anthropologists, geographers, professionals in our respective and often overlapping fields, begin to list sites as important and worthy of preservation. We cite their universal qualities, their authenticity, and their contribution to knowledge about the world at large as evidence of their significance. We often create revenue streams and training/conversation opportunities through such campaigns. But do we build social equity through the stories that are told, the jobs that are created, and the revenue from marketed tourism? What of Antigua as a UNESCO World Heritage Site? Does it mean the same thing for the Ladino and Cakchiquel populations? There is emerging research and literature that takes up some of these concerns, but none I have found address Antigua specifically.[6] There is life in the ruins, but there is a cultural and economic disparity between the former Spanish colonial capital and contemporary Guatemalan context that surrounds it.

[Figure 10. This image, taken between 1899 and 1926, could easily be captured in Antigua today. An indigenous woman selling wares in Parque Central. Arnold Genthe. Library of Congress.]

Recommended reading:

Elizabeth Bell, Antigua Guatemala: The City and Its Heritage (La Antigua Guatemala: Antigua Tours, 1999)

George F. Guillemin, “The Ancient Cakchiquel of Iximché,” Expedition 9 no. 2 (Winter 1967): 22-35

W. George Lovell, “‘Not a City But a World’: Seville and the Indies,” Geographical Review 90 no. 1/2 (January/April 2001): 239-251

W. George Lovell, “Surviving Conquest: The Maya of Guatemala in Historical Perspective,” Latin American Research Review 23 no. 2 (January 1, 1988): 25-57

Sidney D. Markman, “The Architecture of Colonial Antigua, Guatemala, 1543-1773,” Archaeology 4 no. 4 (December 1951): 204-212

Sidney D. Markman, “Las Capuchinas: An Eighteenth-Century Convent in Antigua, Guatemala,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 20 no. 1 (March 1961): 27-33

Sidney D. Markman, “Santa Cruz, Antigua, Guatemala, and the Spanish Colonial Architecture of Central America,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 15 no. 1, Spanish Empire Issue (March 1956): 12-19

Alfred Neumeyer, “The Indian Contribution to Architectural Decoration in Spanish Colonial America,” Art Bulletin 30 no. 2 (June 1, 1948): 104-121

Robert C. Smith, “Colonial Towns of Spanish and Portuguese America,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 14 no. 4, Town Planning Issue (December 1955): 3-12

Susan Migden Socolow and Lyman L. Johnson, “Urbanization in Colonial Latin

America,” Journal of Urban History 8 no. 1 (November 1, 1981): 27-59

John J. Swetnam, “Interaction Between Urban and Rural Residents in a Guatemalan Marketplace,” Urban Anthropology 7 no. 2 (Summer 1978): 137-153

Stephen Webre, “Water and Society in a Spanish American City: Santiago de Guatemala, 1555-1773,” Hispanic American Historical Review 70 no. 1 (February 1990): 57-84

[1] See Ferd C. Valentine, “People and Places in Guatemala,” Manhattan 1 no. 6 (June 1883): 424. The Manhattan was a short-lived illustrated literary magazine; Arthur M. Beaupre, “Antigua, Guatemala, and Its Ruins,” Outing, an Illustrated Monthly Magazine of Recreation 35 no. 1 (October 1899): 50; “Antigua Colonial Ruins Perennial Travel Lure,” Daily Boston Globe April 13, 1952: A18.

[2] Bonnie Lynn, “Antigua, Guatemala: Break Out of Your Comfort Zone,” World & I 26 no. 9 (September 2011): 5.

[3] Joshua Wolfe Levy, “The Making of the Gringo World: Expatriates in La Antigua Guatemala,” (PhD diss., University of California Berkeley, 2007), 7.

[4]

Ana Beatriz del Rosario Linares Muñoz,“Ruin Revival in Antigua Guatemala The Interpretation, Integration and Adaptive Reuse of a Fallen Eighteenth Century Masterpiece,” (Master’s thesis, Columbia University 2007).

[5] See Elizabeth Bell, “Antigua Guatemala celebrates its 34th anniversary UNESCO World Heritage Site” Revue October 1, 2013 http://www.revuemag.com/2013/10/antigua-guatemala-celebrates-its-34th-anniversary-unesco-world-heritage-site/ and “Antigua Over the Years,” Revue March 1, 2014 http://www.revuemag.com/2014/03/antigua-over-the-years/

[6] See Michelle Fawcett, “The Market for Ethics: Culture and the Neoliberal Turn at UNESCO,” (PhD diss., New York University, 2009); Ian Hodder, “Cultural Heritage Rights: From Ownership and Descent to Justice and Well-being,” Anthropological Quarterly 83 no. 4 (Fall 2010): 861-882; and Jason Ryan and Sari Silvanto “World Heritage Sites: The Purposes and Politics of Destination Branding,” Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 27 (2010): 533–545.

Leave a commentOrder by

Newest on top Oldest on top